U.S. denies Iranian line umpire the necessary visa to work at U.S. Open

The 88 officials scheduled to work tennis' U.S. Open come from India and China, Egypt and Romania, Hungary and Russia, and Venezuela and Brazil; in all, the officials come from 33 countries. Many require visas to enter the United States and officiate the U.S. Open, and all the officials who sought visas were approved for the 2014 tournament.

Except one.

His name is Adel Borghei, and he comes from Iran. He is certified as a silver badge referee (the second-highest level, behind gold) and a bronze badge chair umpire (third-highest). He has refereed or umpired tennis tournaments in more than 30 countries, including Wimbledon (eight times) in England, the Australian Open and the U.S. Open. Borghei, in fact, worked America’s biggest tennis tournament just last year.

U.S. Open draw winners and losers

But when the main draw begins on Monday, Borghei will be home in Iran -- not clad in navy blue duds like the rest of the U.S. Open officials. It’s not because he didn’t want to work the U.S. Open, or that he wasn’t among the officials selected. He does, and he was. It’s not like he didn’t apply for a visa. He did, twice.

It’s complicated.

Full disclosure: I wrote about Borghei last August for The New York Times. He had received a letter from the United States Tennis Association that stated he could not work the U.S. Open in 2013 because of United States' sanctions against Iran. Turns out that wasn’t exactly true. He had the wrong type of visa, and it prohibited him from working in America.

Borghei eventually logged on his computer to book a flight home to Iran last August just days before the tournament was scheduled to start, only to receive a call that he never expected. The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) had fast-tracked what they call a specific license in record time, four days after it became aware of Borghei’s plight. That, combined with the visa he had obtained, meant he could work the U.S. Open. He was in.

WERTHEIM: Insider tips and advice for spectators attending the U.S. Open

The stories didn’t make a big splash, but Borghei did officiate at the 2013 U.S. Open, and OFAC did create two general licenses that, according to its news release, “authorize certain humanitarian-related activities by nongovernmental organizations in Iran and athletic exchanges involving Iran and the United States.” The latter fell under General License F. Borghei, at least in part, had contributed to a change in U.S. law. He did one interview at the U.S. Open -- avoiding the subject of politics -- then went back to work, blending into the background like referees are supposed to do.

The story had a happy ending, or at least it seemed to. Borghei’s lawyer, Farhad Alavi of the Akrivis Law Group, told me, “An exchange like this can definitely help relations. The more issues like this come to light, the more it highlights how these sanctions can impact individuals, the unintended consequences. This is a positive step forward. Reason won the day.”

Roger Federer on historic career: 'I never thought it would be like this'

This year, reason was double-bageled. Borghei applied for a U.S. visa at the consulate in Warsaw, Poland -- the same place that granted him a visa last year before all the fuss. But this time, they refused to grant him the visa; the officials there referred to last year’s events and said he needed a working visa in order to work at the U.S. Open. He says he was the only referee who was told he needed that type of visa, and as far as the USTA can tell, his contention is correct. So Borghei applied again at the consulate in Toronto, when he worked the Rogers Cup. Again, he was denied.

There’s no fast track this year and no apparent options, because even if the Treasury Department wanted to help Borghei, the decision of whether or not to approve his visa ultimately rests with the consulates. That’s their call, and it doesn’t have to make sense.

The USTA sent multiple letters to the state department on Borghei’s behalf. One was signed by F. Skip Gilbert, the U.S. Open tournament manager; another was emailed by Dan Malasky, the USTA’s chief counsel. The letter from Gilbert says the USTA has “no objection to the visa being issued.” Malasky's email says Borghei is “one of the best line officials in the world.”

“This is a big blow to the efforts of the administration to increase athletic exchanges between these countries,” Alavi said this week.

NGUYEN: Which of the U.S. Open favorites are most likely to win?

He didn’t want to sound too critical of the government. The consulates have the right to not issue visas, just as they have the right to issue them. But … “A lot of people benefited, at least in theory, from the new license last year,” Alavi said. “It was a good thing. Now they’re denying him the very same visa he got last year, before the general license was even issued.”

All of this cost Borghei, too. He paid to stay in Poland and Canada to wait to hear back on his applications, paid for food and taxis and fees for those applications, paid to change his flight from Toronto so he could go home to Iran. He estimated that after all of his costs, even with what he made at the U.S. Open, he would have been down about $1,500. And that doesn't even include the cost to change his flight to go back to Iran earlier than expected. All of this for what?

At the very least, Borghei would seem to deserve a better explanation for why his visa application was rejected. After asking a few folks at the State Department, they sent over a general list of reasons for visa denials.They declined to comment on Borghei’s application specifically, citing confidentiality required under the Immigration and Nationality Act.

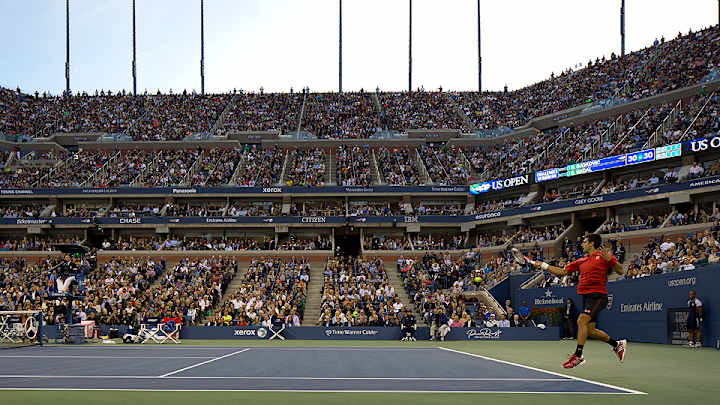

The best part of the U.S. Open is how much of a melting pot the whole thing is. There are players from all over the world, fans of every ethnicity, dozens of languages, all types of food. But not for Adel Borghei, and that’s a shame, because all he wants is to be a part of it.