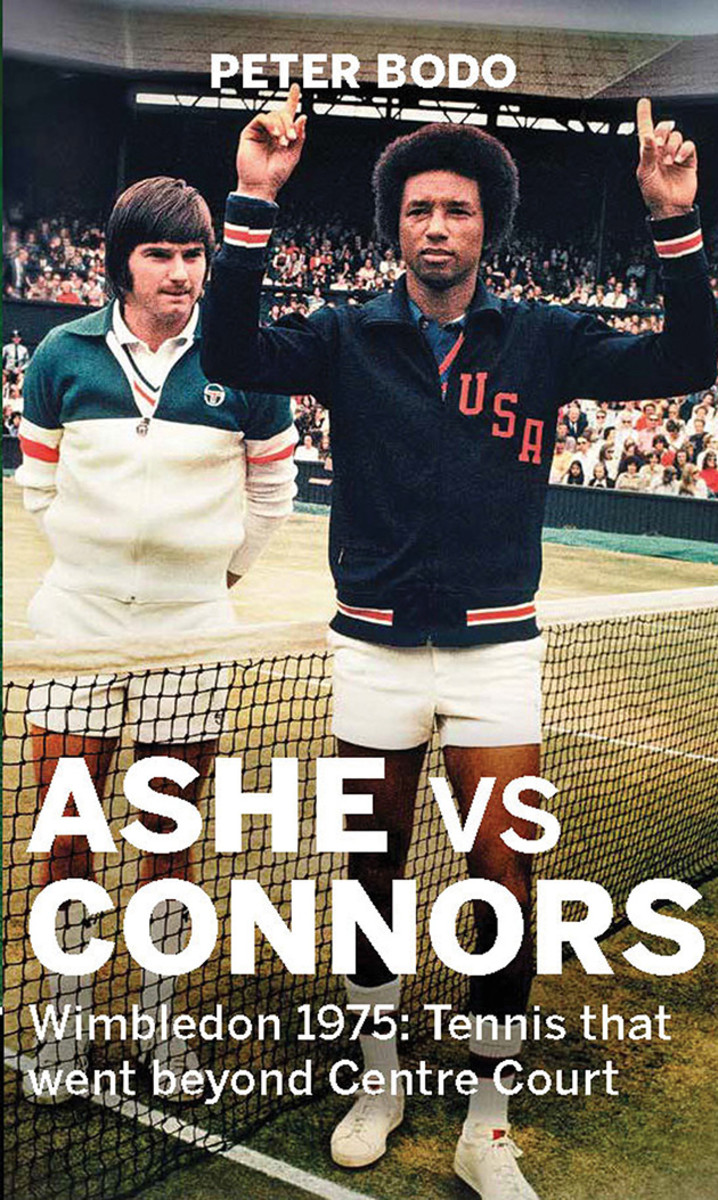

Book excerpt: Peter Bodo on Ashe vs. Connors at Wimbledon in 1975

Excerpt from "Ashe vs Connors: Wimbledon 1975: Tennis that went beyond centre court" by Peter Bodo to be published on May 28, 2015 by Aurum Press, $26.99. Copyright © 2015 by Peter Bodo. Reprinted by permission of Aurum Press. All rights reserved. Order your copy on Amazon.

After dinner at the Playboy Club, Ashe, Charlie Pasarell and Donald Dell return to the Westbury Hotel to relax and strategize a bit before turning in. All of them are thinking similar things. Earlier in the day, Ashe had taken a call from US Davis Cup captain Dennis Ralston, yet another friend and Dell client who is mortified by Connors and his attitudes and antics.

Ralston, a Wimbledon finalist in 1966, advised Ashe to play to Connors’ forehand, keeping the ball low. ‘He isn’t good at those balls,’ Ralston said. ‘He makes a lot of errors when he has to hit up on a low ball, compared to waist-high balls. He doesn’t miss many waist-high balls.’

Ashe lays this out, and his companions nod and agree with the assessment. Pasarell then spells out in detail how Pancho Gonzalez mastered Connors in that unforgettable match of 1971. For all the power of his famous serve, Gonzalez was no ball basher. Once the ball was in play, Gonzalez had a wonderful toolbox to draw upon, ranging from gently struck slice backhands and sharply cut volleys to an assortment of dinks, chips and drop shots. His catlike quickness enabled him to outmaneuver and outfox opponents.

Pasarell was convinced that Gonzalez’s blueprint remained valid, for Connors’ game had improved but not really changed in the four-year interim. Pasarell knew Ashe was intelligent and skilled enough to embrace it. If he could cling to his strategy and make it work in the face of Connors’ barrage of flat, stinging groundstrokes, it would also give the underdog a psychological advantage.

Ashe and company decide that he would plug away at Connors’ backhand return. He would feed Connors relatively slow balls, right down the center of the court, preferably forcing him to hit low forehands.

The other addition is a tactic with which Ashe has already experimented, albeit with mixed results. He will dust off the most seldom used weapon in his arsenal, the lob.

Connors closes on the net aggressively, thus he’s vulnerable to the lob – especially the relatively low trajectory lob. Also, at 5ft 10, Connors is relatively short. His reach, especially on the backhand side (where he is hampered by his two-handed grip even on the backhand smash), is limited.

That this is the first meeting of the men on grass courts just might work out to be an enormous advantage for Ashe. The properties of the surface seem favorable to his strategy and tactics. But it will take enormous skill, as well as nerve, to pull off the upset. Should Ashe play with anything less than precision, or dip his brush into the wrong color on his palette at any given moment, he will surely get the ball shoved right down his throat. He will be this year’s Ken Rosewall. Spectators might walk away muttering and shaking their heads, ‘What was wrong with Ashe? He didn’t even look like he was trying. Connors killed him.’

The four man ‘brains trust’ (including Ralston) has come up with a game plan that makes Ashe feel that all bets are off – despite his three previous losses to Connors, despite his 11-2 underdog status. It’s a plan that even that brilliant lone wolf Pancho Segura might be hard put to match. But Segura won’t even get a chance to match wits with Ashe’s coterie. He’s been driven off by jealous Gloria Connors, and Jimbo is left twisting in the wind.

Proud, brash and confident, he doesn’t even know it.

It is the day of reckoning: Sunday, 5 July.

Connors did not practice at all on Saturday, the day of the women’s Wimbledon singles final. He was resting his leg. Now, on Sunday morning, he is warming up on a court in Wimbledon’s hinterlands, a court where they usually play junior matches. But the early arrivals at Wimbledon are among the most determined and knowledgeable of fans. They know Connors and Ashe will be out there, somewhere, having their pre-match warm-ups. These usually consists of a fairly light hit, and if the fans are lucky they might get to see their idols goofing around, hitting trick shots and trying to stay loose.

Connors does not disappoint. He is put through his paces by his pal Ilie Nӑstase. It’s hard to tell if it’s because Connors wants to protect his injured leg, or maybe he feels extremely confident, but he’s in a particularly chipper mood. Perhaps it’s that, across the net, the gifted mimic Nӑstase is doing a hilarious imitation of Ashe – from his service motion right down to the way he walks. And the fans gathered around the court are loving it.

[pagebreak]

Ashe will warm up later, right before the final. In fact, part of his game plan is to go out to play the match while still sufficiently exercised to perspire. Ashe believes it’s imperative for him to get a quick start, to get Connors off-balance, and early. It will help if he’s already elastic and warm.

Ashe recruits Ray Ruffels to warm him up, partly because, like Connors, Ruffels is a lefty. Just as important, though, at least from a karmic point of view, Ruffels has already had the honor of warming up two previous Wimbledon finalists – both of whom went on to become the champion. Of course, Ashe is a rational man. But even a rational man can see that warming up with Ruffels certainly can’t hurt.

Ruffels is somewhat puzzled during their spirited warm-up. At one point, as he collects balls at the net, he asks Ashe, ‘I can’t understand this, Artie. You’re always lobbing today. But everybody knows you never use the lob.’

Ashe smiles at the question and offers some obtuse explanation without going into great detail.

Down in the lobby of the Westbury Hotel, waiting for Arthur Ashe on the morning of the Wimbledon final, Donald Dell has an idea. He finds a piece of hotel stationery and writes down three things for his friend to remember: keep the ball low, and mostly on Connors’ forehand side; serve him wide to the backhand; use the lob.

When Dell really wants to get Ashe’s undivided attention, he always calls him ‘lieutenant’. Before Ashe disappears into the bowels of Centre Court to prepare for the match, Dell calls out, ‘Lieutenant.’ He hands Ashe the note. ‘Good luck.’

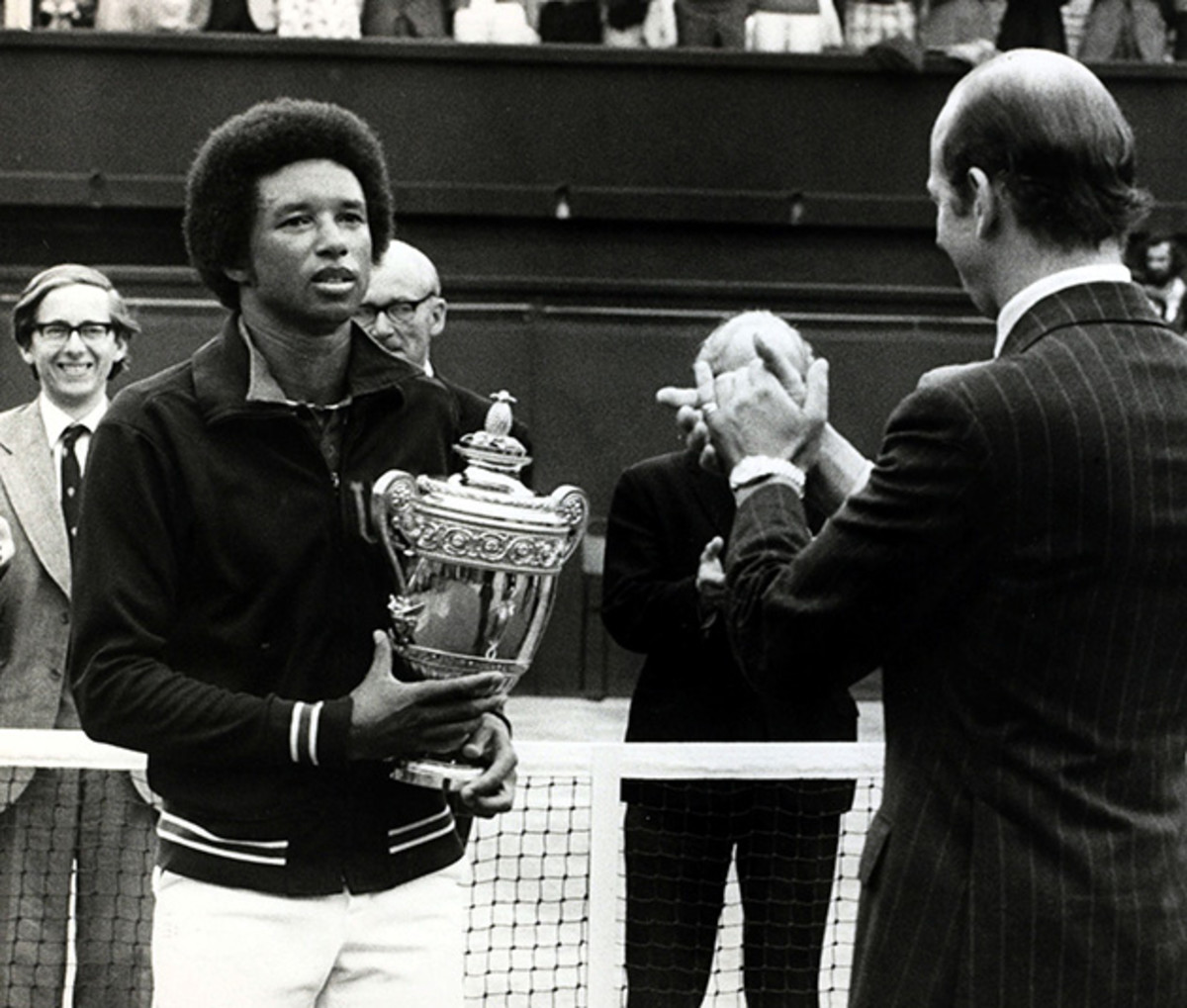

A grand total of 338,000 spectators have trooped through the turnstiles at Wimbledon during the 1975 tournament, establishing a new record. Perhaps the luckiest of them all are assembled for the men’s final – the first between Americans in a full twenty-nine years. Many of them understand that they may be about to witness yet another passing of the torch into the eager hands of Jimmy Connors. The young American’s international celebrity is at a peak; in late April he made the cover of Time magazine back in the US, a privilege rarely bestowed upon an athlete, along with the headline, ‘Storming the Courts’. But there is no sign of overwhelming, pro-Connors sentiment in this crowd. And that can be attributed to the popularity of Arthur Ashe. No black man has ever been champion at Wimbledon, and if you were to create an appropriate one to achieve that honor you might come up with someone like Ashe. The contrast he embodies with Connors is inescapable and manifest on almost every level, and that accounts for some of the palpable tension in the air, which is otherwise soft and still. The temperature is ideal, and the overcast skies absorb the sunlight and redistributes it softly and evenly. Neither man will have trouble picking a lob out of the sun on this day.

During the preliminaries, Jimmy Connors appears loose and confident. Squinty-eyed, he grins at the photographers who record the coin toss, and fires off some wisecrack. He glances covertly at the player guest box, which is across Centre Court from the chair umpire, to his right, and just above one of the two main scoreboards. Gloria sits there, flanked by Bill Riordan on the right and – presumably in place of exiled coach Pancho Segura – British actress Susan George. The box is shared by the special guests of the finalists, the Connors contingent on the right side, Ashe’s supporters on the left. Alongside Connors, Arthur Ashe stands with his brow furrowed, as if he’s trying to remember a telephone number, or perhaps he’s wondering where he’s seen that stunning woman sitting next to Gloria Connors. He bites his lip.

The men are ready. The crowd is fidgety, a few of the patrons as close to the court as the first row of seats along the side line nervously puff on cigarettes. Their anxiety may be explained by the fact that for the first time in Wimbledon history, bookmakers are allowed in the grounds. Fans who attend Wimbledon are generally a conservative lot, but there are a fair number of oversized collars, lively print shirts with the three top buttons open, leather jackets and belled sleeves on display.

Having won the toss, Connors elects to serve first. He accepts two balls and stands at the baseline. As the umpire intones, ‘Connors to serve. Quiet please’, the noise subsides. Jimbo looks down at his shoes, leisurely bouncing a ball. He’s like a schoolteacher, waiting for the children to settle down before beginning class.

‘Play.’

Connors is still in no hurry. He lifts his head, looks up at the gallery as he basks in this moment, and smiles knowingly. He appears a man in full control of his destiny, perhaps even smug. It’s a surprisingly cavalier attitude, but one to which Connors might feel entitled given his history with Ashe.