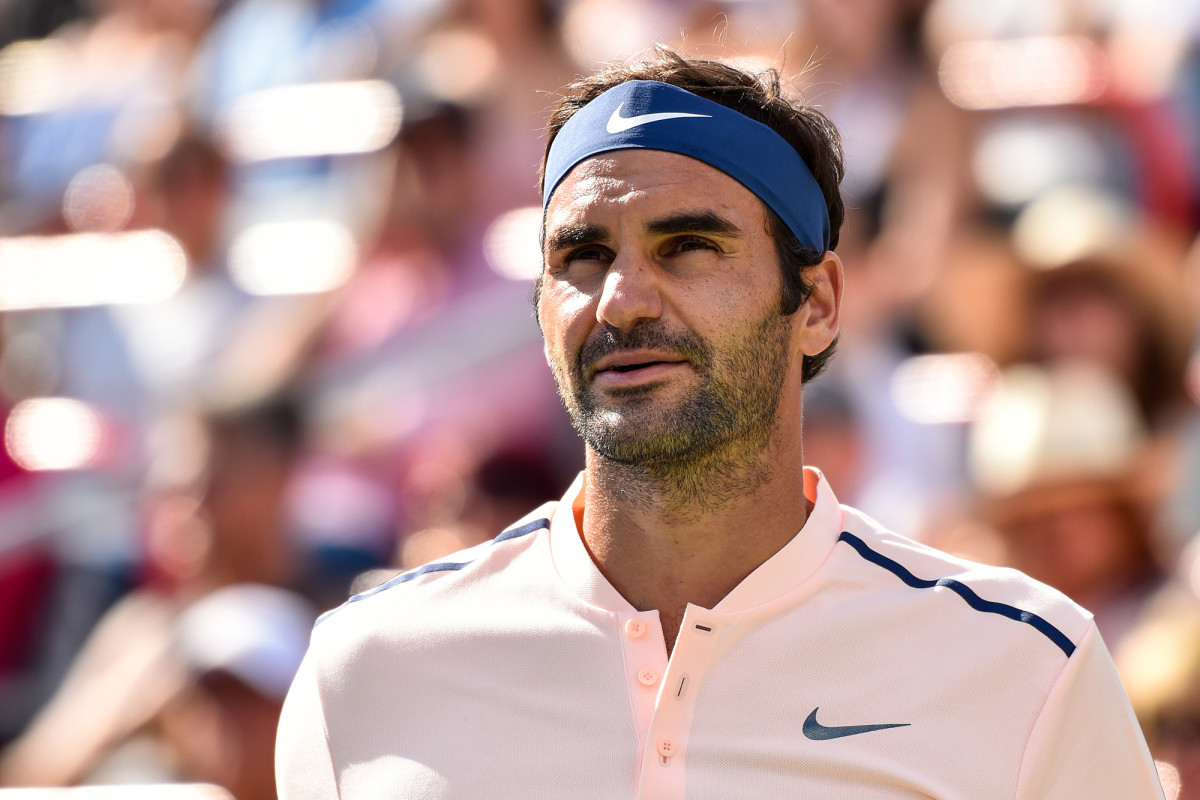

Roger Federer LLC: How the G.O.A.T. Got to the Top of His Game, in Businesslike Fashion

This story appears in the Aug. 28, 2017, issue of Sports Illustrated. Subscribe to the magazine here.

There are, in fairness, some populist touches to the U.S. Open, the world's largest tennis event. The $60 grounds pass remains one of the great values in sports, entrée to watch dozens of matches for as long as 12 hours. But make no mistake: Overall, the U.S. Open is a province of the superelite, a redoubt of privilege.

Just stroll through the parking lots in Flushing Meadow and you'll catch the first unmistakable whiff of wealth. The roster of cars is a testament to the forces of globalization. Ferraris and Jaguars and Teslas, Mercedes and BMWs, parked alongside one another, like names on the draw sheet.

The aroma gets stronger inside the grounds. Bill Ackman—a hedge fund billionaire whose passion for tennis is so great that he recently installed a court on the roof of his midtown Manhattan offices—sits courtside at most sessions, tennis's answer to the NBA's Jimmy Goldstein. The luxury suites are filled with would-be masters of the universe, drinking cocktails and eating canapés in air-conditioned sanctuaries. (One prominent New York City real estate developer with a striking hairstyle and skin the color of Roland Garros clay has been an Open regular for decades.) During the fortnight, Steve Schwarzman, CEO of the Blackstone Group, a private equity behemoth, has hosted dinners for star players, most notably Novak Djokovic.

Earlier this summer, a longtime ticket holder was surprised to learn that the price for his fourth-row tickets was being jacked up, from $17,560 to $23,960, a 36% increase from the previous year. He made the purchase anyway, but complained to his USTA sales rep. The one-sentence response he received was the perfect embodiment of the event's unapologetically profiteering ethos: "Pricing [was adjusted] to reflect the true market demand for every row and seat in the stadium."

Yet, all these Captains of Industry and denizens of Hedge Fund Nation could all learn some management tips from tennis's de facto CEO.

Roger Federer might come to New York City this week as a 36-year-old devoted husband and father of four, with a temperamental back. But make no mistake: This is no legacy brand playing for nostalgia. Federer LLC remains the bluest of blue chips, a robust enterprise that spits out profits, beats expectations and pleases its investors.

U.S. Open 2017 Preview Roundtable: Bold Predictions, Storylines and More

Federer began tennis's fiscal year by winning the Australian Open, outperforming his rival, Rafael Nadal, in the final. He then won big-ticket events in Indian Wells and Miami, taking down Nadal again en route to both titles. In July, Federer won Wimbledon—for a record eighth time—without dropping a set. He now seeks another quarter of growth in New York City. A sixth U.S. Open title would give him an even 20 majors over his unrivaled career and seal this as a golden season, even by his standards. "Honestly, I'm incredibly surprised how well this year is going, how well I'm feeling, how things are turning out to be on the courts, how I'm managing tougher situations, where my level of play is on a daily basis," he says. "I knew I could do great again maybe one day, but not at this level."

Federer, of course, doesn't play tennis as much as perform it. His lavish skills and artistic impulses and fetching shotmaking are all part of the brand's appeal. But if there's something otherworldly about Federer, there's also something pragmatic and rational. (He is, after all, Swiss.) At his core, Federer is a utilitarian who makes decisions to maximize output and efficiency. He treats his career like the business venture that it is. As the suits in the suites sit open-mouthed watching Federer, they can also find plenty of lessons to apply to their day jobs.

LESSON 1: CHANGE IS DIFFICULT, BUT OBSOLESCENCE IS WORSE

In tennis, as with investment funds, past performance is no guarantee of future results. Before this season, Federer had gone 17 majors without a title. But he continued innovating and making personnel changes. He switched to a larger racket. He released and hired coaches. He tinkered with his playing patterns. Most notably, he forced himself to fight risk aversion and blast through his one-handed backhand. Even before he reaped the fruits of his expansive mind, the message he sent to the rest of the field—my vaulting ambition is such that I'm willing to change the way I do business to remain competitive—was powerful.

How to Eat Your Way Through the 2017 U.S. Open

LESSON 2: DON'T LIVE QUARTER-TO-QUARTER

The rankings are tennis's equivalent of a stock price. While some players are concerned with every fluctuation—and the effect of upticks and slides—Federer plays the long game, willing to endure setbacks to peak at the right times. After winning the Miami Open in early April, he promptly sat out the clay season, wary of the price it was likely to exact on his body. The decision cost him the No. 1 ranking, but it was validated at Wimbledon, where he was conspicuously fresh and rested. Likewise, earlier this month, Federer chose not to play through back pain and defend his Cincinnati title. Withdrawing meant giving up ranking points and prize money and adjusting his schedule. No matter. Armed with a clear mission—winning the U.S. Open—he sacrificed short-term for long-term.

LESSON 3: EMBRACE RIVALRY

If competition brings out the best in us, what does rivalry—a sort of turbo-competition—do? There are all sorts of social science data that bear out its benefits. Runners have faster times when racing against a rival, to give just one example. There's ample anecdotal evidence as well. When the history of Apple is written, there will inevitably be a reference to the hinge point moment when Steve Jobs declared "Holy War with Google." For years, Federer seemed to retreat from a rivalry with Nadal, intimidated by the fierce intensity on the other side of the net. Recently, Federer has realized that if he's the Mustang to Nadal's Camaro, it's ultimately to his benefit. "At last," says Mats Wilander, winner of seven majors, including the 1988 U.S. Open, and one of the sport's most astute observers, "Federer is comfortable playing Nadal." While Nadal still leads their head-to-head meetings, 23–14, Federer has taken the last four, no small factor in his resurgence.

LESSON 4: LEADERS SET THE CULTURE

Federer gives lie to the notion that top athletes must have a nasty streak. For all the metaphors bestowed on the guy, you will not hear him likened to "an assassin" or a "cold killer" or, for that matter, "a tiger." Federer generally performs with a smile on his face and an unruffled demeanor. He treats his colleagues as opponents, not enemies. He's played his entire career absent controversy, much less scandal. This affects the entire tennis culture. Note how many players today sign autographs as they leave the court, even after defeat. Note how few act cantankerously. The message is clear: If the guy at the top discharges his duties with not just professionalism but with joy, and he's generous with time and refreshingly candid, what excuse is there for a lesser player not to do the same?

LESSON 5: BALANCE IS KEY

Federer is praised for perfect weight distribution on his strokes, and he goes about his business with remarkable equilibrium too. He doesn't cut corners, but neither is he a workaholic. He never appears rushed, and he is devoted to his family. His offseason is sacrosanct, as are birthdays. (Scheduling is helped by having two sets of twins.) As 2003 U.S. Open champ Andy Roddick once put it, "Roger has a way of bending time." Much as savvy companies enforce employee vacation time, Federer knows that sometimes working less enhances productivity and helps stave off burnout.

Mailbag: Injuries Will Be Common Theme at U.S. Open, But What's To Blame?

When the U.S. Open kicks off on Monday, there will be others fighting Federer for market share. Nadal comes to Flushing Meadow as the top seed, having played splendidly all year, especially at the French Open in June. Alexander Zverev is a brash start-up, a 20-year-old German who beat Federer in the finals of the Canadian Open on Aug. 13 and is quickly gaining control over his considerable skills. Marin Cilic of Croatia reached the finals of Wimbledon last month and won the U.S. Open in 2014. He's the most recent champion in the field, as defending champ Stan Wawrinka is recovering from knee surgery, and 2015 winner Djokovic is out with a right elbow injury.

Still, we predict another strong quarter for Federer. He's spent the whole year forcing forecasters to revise their projections upward. Says here he wins again. No need to hedge.