Stoneman Douglas Survivor Finds a Moment of Normalcy at the Delray Beach Open

DELRAY BEACH, Fla. — It was twilight when I arrived at Saturday night’s Delray Beach Open semifinal between Frances Tiafoe and Denis Shapovalov. A security guard outside the tournament’s media center greeted me with a friendly smile and motioned for me to open my bag.

We exchanged pleasantries as he unzipped the largest pocket of my backpack. He delicately moved my laptop and rifled through some notebooks, peering into the depths of my bag, and then unzipped the next pocket. I apologized for my backpack’s myriad compartments. He shrugged.

“We’ve just gotta be careful,” he said. “You know, after what happened with those kids.”

Those kids. Ten days earlier, 17 people—14 of them children—were murdered less than 25 miles southwest of the Delray Tennis Center. A 19-year-old gunman, armed with a semiautomatic AR-15 rifle, shot and killed 14 students and three teachers at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla. Several others were wounded. In one afternoon of terror, Parkland changed forever. Marjory Stoneman Douglas, nestled in a quiet Miami suburb, became one of those names—like Sandy Hook, Pulse, Columbine and too many others—synonymous with a mass shooting.

During a changeover in the doubles match on Saturday, which preceded Shapovalov–Tiafoe, the public address announcer introduced Richard Doan of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas tennis team. With those words—Stoneman Douglas—an uneasy quiet came over the crowd, which seemed uncertain how to react.

Richard walked onto the court, where an official accompanied him over to a Porsche, a sponsor’s gimmick that sits in the corner behind a baseline during the tournament. He offered a smile and a polite wave as the crowd belatedly started to applaud. He and his girlfriend climbed into the convertible. Richard, who attends the tournament every year with his family, had always wanted to sit in that car during a match.

Around 2:20 p.m. on Valentine’s Day, Richard, a senior at Stoneman Douglas, was in the school’s newspaper room when a fire alarm went off. Surprised, because the school had held a fire drill earlier that day, he and his classmates started filing downstairs toward an evacuation zone. But they quickly encountered teachers screaming in panic. Run! Run! Richard sprinted upstairs to his classroom as directed, still unsure what was happening. He recalled a rumor that the school wanted to stage an active shooter drill at some point. Was this it?

The wail of sirens and the din of helicopters circling overhead indicated that it wasn’t. They followed Code Red protocol: doors locked, lights off, windows closed. As the situation became clear, around 20 students and a teacher, initially huddled quietly in the corner of the classroom, crowded into a closet. Cramped together for the next two hours, they quietly texted family and followed the news online. There was a shooter on campus. They had no idea where he was. Richard’s phone blew up with text messages from people he hadn’t spoken to in years, from all over the world—even his parents’ birthplace of Vietnam, where it was the middle of the night. Text messages to his family wouldn’t go through, so they didn’t know whether he was safe. The gunman, a former Stoneman Douglas student who had been expelled, was at large.

Inside the closet, students were sobbing, fearing for their lives. Richard was mostly in disbelief. “You never think it’s going to happen in your school,” he says. “Nothing happens in Parkland.”

When police—dressed in full SWAT attire—entered the classroom with weapons drawn and flashlights on, Richard didn’t know whether he was about to be shot or saved. Hands up. He was safe. But elsewhere, good friends of his were wounded. Carmen Schentrup, a recurring classmate of Richard’s in AP courses, was killed. She would have turned 17 last Wednesday.

Since the shooting, unfathomable pain and righteous anger have fueled a rejuvenated, vigorous movement against gun violence. Stoneman Douglas students are leading a determined campaign, officially called the Never Again Movement, to change gun laws around the country, seizing the political moment and impossibly defying the fatalism that has accompanied mass shootings since the failure to act after Sandy Hook, when 20 young children were gunned down at an elementary school. A “March for Our Lives” is planned for March 24 in Washington, D.C. Parkland teenagers are leading a genuine political movement. Overnight, Richard’s life changed: He’s no longer preoccupied with prom, graduation and college. He’s thinking about how to change a nation.

“Everything I do is for those 17 lives. Whether it’s just playing tennis and representing our school, or just going to class and studying hard, or fighting for change and talking to the media—it’s all for them,” he says. “Because we’re going to make sure that they do not go in vain.”

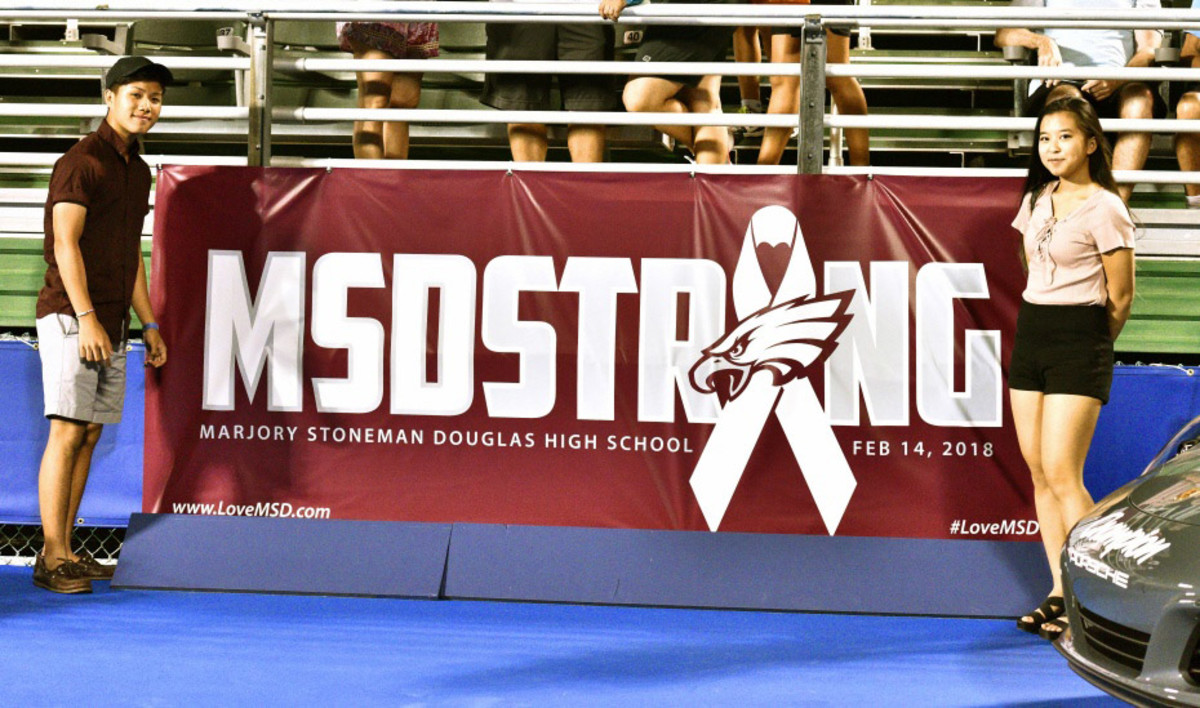

Parkland loomed over the Delray Beach Open: There were moments of silence, #MSDStrong banners, tributes to the fallen, supportive comments from players and free tickets for Stoneman Douglas students. But for Richard, the tournament was a rare escape from his new reality. On Saturday night, less than two weeks after cowering in a closet, Richard was lounging in a convertible Porsche on the invitation of the tournament, watching rising stars Frances Tiafoe and Denis Shapovalov warm up. Richard, a lifelong tennis fan who grew up idolizing Rafael Nadal, conducted the coin toss and posed for photos with players barely older than the victims—Tiafoe is 20 and Shapovalov is 18.

The match started. After days of praying, grieving and fighting for change, Richard had returned to a familiar environment: the tennis court. When he was a boy, his parents signed him up to play tennis because they thought he had too much energy. He came to love the game not just because he was a natural, but also because he realized it could last him a lifetime. Now, years after he first picked up a racket, he and his girlfriend—joined by his mother and older brother, who were in the stands—watched some tennis.

“It’s kind of relaxing, just to hear the ball go back and forth—it’s soothing,” Richard says. “It just gives me the time to take a step back, breathe and relax a little bit before I just go back to advocating for change again tomorrow. And the day after. And probably for the rest of my life—this is something that I’m going to be talking about until something is done.”