Into the NFL's heart of darkness: How I fell for the Oakland Raiders

In the year 2014—the 95th season of the National Football League; 55 years after the founding of the American Football League; 54 years after 28 rookies and 14 veterans were shunted from Minnesota to Oakland and christened the Raiders; 38 years after those Raiders first hoisted the Lombardi Trophy; 32 years after they left Oakland for Los Angeles; 20 years after they moved back; 12 years after their last playoff appearance; seven years after they signed something named JaMarcus Russell to a blockbuster contract to lead the franchise back from the abyss; four years after they released him halfway through that contract; three years after they last won more than two consecutive games; 19 months after they started covering 10,000 seats each game with a tarp to prevent television blackouts for low attendance—I decided to join Raider Nation.

I know nothing about football: to begin with. America’s Favorite Sport simply never crossed the threshold of my home. It was a long, brutal, and boring abstraction unworthy of further consideration. Football was something that just never happened for me.

But lo, upon moving back to my native Bay Area this fall after seven years away—college, grad school, work—I realized that I was actually bored of shrugging my shoulders at the most popular game in town; bored of missing out on bar banter; bored, I guess, of Sundays.

Why football, though? Why—with the many recent horrible revelations about off-the-field misconduct and in-helmet trauma trickling out—would I want to follow such a thing?

The answer is: I don’t know. People like it. Condi likes it. Maybe there was a a Sunday afternoon–shaped hole in my life; maybe my fellow Americans knew something I did not.

My sport had always been baseball. My Giants, of course, were easy to rally around. They had lovable oddballs—Hunter Pence, the Kung Fu Panda, Tim Lincecum—and they had stars. Best of all, they were good: It’s not hard to find room in your heart for a team that brings home three World Series rings in five years.

The Raiders, however, are not good. If there is a Giants bandwagon, it is a bandwagon filled with nice people and nice things, heading west to the land of milk and honey with oxen to spare. The Raiders bandwagon, if it can be called that, is a monster truck with the brakes cut—quite possibly by the passengers themselves—careening down a rocky hillside, the fence protecting onlookers just a little too low for comfort.

The Raiders are not headed for milk and honey. They do not want milk and honey. To paraphrase Nelson Algren, it’s a team with (very often literally) a broken nose.

Yet here I was, back home, football allegiance undeclared. I had a choice, I guess, between the Raiders and the Bay Area’s other football team—the team that entered 2014 coming off back-to-back-to-back appearances in the conference championship game; the team that’s been to the postseason 10 times in the last 20 years. To be honest, though, I never really considered being a Niners fan. Hunter S. Thompson, himself a proud citizen of Raider Nation, once called Oakland’s fans “beyond doubt the sleaziest and rudest and most sinister mob of thugs and wackos ever assembled.”

I mean, how could I not?

But can you just sign up that way? Could I simply announce to the world that I was a Raider fan, pick up a jersey on eBay, hot glue some rhinestones to an eye patch, and carry on?

Nobody likes a bandwagoner, but that usually applies to teams that don’t bury footballs in the corner of their practice fields. Can you ever be a real fan if the effort to become one is deliberate?

And then there’s the matter of the actual football. My knowledge of the sport is, shall we say, shaky: something about downs, big people, and very expensive ad time. Neither my football-team-less high school nor four years at the University of Chicago—school of the very first Heisman Trophy winner and whose stadium was later shuttered, used for early Manhattan Project experiments, and then torn down to build a library—did much to advance my knowledge. In truth, most everything I know about football is from watching Friday Night Lights.

But clear eyes, full hearts, right? On Sept. 15, 2014, I throw my hat in with the 0–2 Oakland Raiders.

I turn to a friend, a Raider fan from his earliest days. Every time he has his Raiders cap on, he starts drawing murmurs from strangers who fall consistently into one of three categories: weird, scary, or weird and scary. Strange women stop him on the street, bouncers nod knowingly. Clearly, he knows the secrets of this kingdom.

Do the Raiders have a rival? I ask him.

“ESPN,” he replies.

Another friend’s roommate, Vince, messages me on Facebook one night. “I hear you’re interested in joining the Nation,” he writes. “Are you open to silver face paint?”

"YES," I tell him. I am so open to silver face paint.

A few days later I sit down with Vince. By this point, I’d confessed my lack of football knowledge, and Vince, wearing the jersey of Sebastian Janikowski—alias SeaBass, Oakland’s 36-year-old, Polish-born, alopecia-afflicted placekicker who is the franchise’s all-time leading scorer and has been arrested for felony drug possession and bribery, the latter because of a simple misunderstanding with a police officer about three $100 bills—is surprisingly nice about it. He hides his shame well as he draws a four-man defensive front on a napkin, and walks me through the positions. There are offensive linemen (freakish giants), defensive linemen (somewhat nimbler freakish giants), and wide receivers (fast). Vince shows me a few basic plays, and I feel pretty good about things.

On Monday, some 12 hours after the Raiders’ 30–14 loss to the Texans (a performance that saw wide receiver James Jones fumble twice during one play), I decide to make my fandom official. “Aspiring Raiders fan,” I add to my Twitter bio. I follow a dozen Raiders accounts: THE OFFICIAL RAIDERS ACCOUNT*, a few reporters, fan clubs. I choose some players I’ve never heard of based entirely on the number of followers they have.

(*The Raiders Twitter account’s name is in all caps. @Seahawks?, @49ers? @Patriots?, @Ravens?, @Saints? @RAIDERS!!! They are the only NFL team that does this.)

I’m thrilled when, 15 minutes later, @FansOaklandRaid follows me back. Then something more sinister happens. I get a DM from “RAIDERNATION NEWS,” demanding that I post something “Shouting Out The #Raiders.” I do not do this, and am summarily unfollowed.

Undaunted, I begin to study. I watch the documentary Rebels of Oakland, a tribute to the 1970s Raiders and A’s and all their mustachioed, winning ways. I watch a 30 for 30. I’m shown “The Autumn Wind,” the Silver and Black’s anthem. It’s excellent. Devoted Raider fan Ice Cube’s twist on the anthem, featured on the official Oakland Raiders tailgate playlist, imagines the opposition crying.

Still, there are some inauspicious signs.

I’m informed—in a way meant, I think, to make me hopeful for rookie Derek Carr—that it’s been 12 years since the Raiders went an entire season with the same starting quarterback. On the Raiders’ Wikipedia page, there’s a lengthy section titled “Coaching carousel,” one whose years end in "–present." The list includes former head coach Tom Cable, who went 17–27 and once caused a defensive assistant’s jaw to break during a meeting—via a cabinet or his fist, depending on whom you ask—purportedly prompting the players to start chanting “Cable, Bumaye,” the Congolese cheer that followed Muhammad Ali before his 1974 Rumble in the Jungle fight against George Foreman in Zaire. It means “Kill him, Cable.”

[pagebreak]

Here are some things that happened in the opening weeks of the Raiders’ 2014 season: A crazed, mid-fumble bicycle kick by Maurice Jones-Drew that sent the ball hurtling ten yards backwards. A potentially game-tying touchdown overturned on a dubious holding call, followed immediately by an interception with less than a minute left on the clock. A different pick with 1:13 to go, SeaBass’s would-be game-tying kick never to occur.

I went to a bar for that last debacle, and watched as the only other person paying any attention to the TV—a guy dressed head to toe in silver and black—sat very still, Raiders cap cocked, speaking to no one. His only show of emotion was a single clap as the Raiders surged—briefly—ahead in the fourth quarter. No one noticed him in a bar full of giddy Giants fans waiting for the NLCS to start.

Oakland, of course, lost that game. The team’s last victory was some 11 months in the rearview mirror. Coach Tony Sparano, whose name I have never not read as Tony Soprano, had been handed the reins after his predecessor notched 10 straight losses. Sparano tries to explain the latest loss to a reporter. “Oakland being Oakland,” he says.

As that game wraps up, that tying kick snatched away, a friend I’d told about my new fandom texts me:

“I feel like you still have time to abandon this.”

Vince invites me to a game with a group of his college friends. Once a year, they descend on the Coliseum, setting up camp at the tailgate and then watching the Raiders win, having chosen the game they think offers the best chance of victory. This year, 336 days after the Silver and Black’s last win, and five losses into the 2014 campaign, they have chosen the NFC West–leading Arizona Cardinals, who, as it turns out, are not very bad at all.

I’m told to bring beer.

It’s eight o’clock on a beautiful Sunday morning in Berkeley when a very blond, very attractive, stroller-pushing couple looks disdainfully at the 30-rack of Coors Light I’m bear-hugging as I hurry toward BART. A man with his daughter on his shoulders does a double take, stopping just short of covering her eyes. I begin to sweat. Finally, across the street from the station, I pass a bearded man who grins at me. There’s a pitbull sniffing at his feet as he lays out a piece of cardboard and takes a seat on the sidewalk. “Now there’s a party. Right on, bro-bro.” (When I return 10 hours later, he’s still sitting on his cardboard in the same spot, but, this time short a 30-rack, he does not acknowledge me.)

The train slowly fills with Raider fans, all of whom—judging by the massive, glittering tangles of beads hanging from their necks—seem to be returning from a specialty Raiders Mardi Gras. A man gets on a few stops after mine with a bottle of Cook’s. “Ready to celebrate,” I write in my notes.

The Coliseum, an enormous, ugly, all-concrete 1964 monstrosity no one likes, lies across a long footbridge from the Coliseum BART station. The footbridge itself—edged in barbed wire and suspended over parking lots, railroad tracks, and a brackish offshoot of the San Leandro Bay—runs parallel to the gleaming new BART station that links to Oakland International. The not-yet-operational line was still doing practice runs that day, drawing admiring coos from bead-laden onlookers.

As I cross—Coors Light box jabbing me in the leg but no longer drawing reproachful looks—I see a cloud of blue-gray smoke hanging over the parking lot: the tailgate. Vans, tents, beer, masks, silver and black everywhere. Fully one-third of stereos seem to be playing “Still D.R.E.” at any given time.

I’ve been promised chaos: cowering Arizona fans ringed by packs of slavering Raider Nationites with homemade weapons, huge men in silver body-slamming one another and burning effigies of Carson Palmer, former players, first grade teachers.

Here, a big discovery: Raider fans are, well … nice.

The atmosphere in the Coliseum parking lot the morning of the Raiders’ sixth loss of the season is carnivalesque. One section actually is a carnival, a fenced-off, family-friendly village of concession stands and raffle draws where you can rock climb or play cornhole with Raiderettes. People are chummy: fans greet each other as they pass; I’m offered food and beer by strangers repeatedly. There are, maybe, some impolitic outfits—a man in spikes strides by, a baby doll dressed in miniature Cardinals gear impaled on a pike in his hands—but for the most part, Raider Nation is downright neighborly.

I’ve dressed, cautiously, in a long-sleeve gray shirt and jeans. Most everyone I talk to eyes me at some point and asks if I support the Nation, a question to which, neighborly fixings aside, I suspect there is a wrong answer. These people also ask me, over and over, if I’m all alone out here? An usher seems assuaged when I point to the portion of the group I’m sitting with: three guys, every one of them over 6 feet tall, 200 pounds, and a former football player. “You’re with those guys?” she asks. “Good.”

Outside the stadium I chat with Frank, a season ticket holder set up under a tent, custom Raiders license plate—RAIDRS2—hanging over his head. He tells me he’s been a fan since 1968, when the team went 12–2.

Frank wears his season pass around his neck, glasses and a Panama hat with Raiders brim giving him a grandfatherly look. His shorts reveal that one leg is replaced below the knee by a silver prosthetic. Frank thinks this’ll be the one to snap the Raiders out of their skid.

Frank is eager to impress upon me the safety of the Raiders experience: his ticket sales rep told him that the Oakland Coliseum is the fourth-safest stadium in the league. I do not mention the 40-foot-high watchtowers set up in the middle of either of the stadium’s parking lots, manned by Event Staff in yellow jackets who are probably not up there to look for people being overly friendly.

Frank worries a little about the state of Raider Nation. “We had a lot of fans. Then when we went to L.A.,”—in 1982; he pauses, sighs—“they became Niner fans.”

He grimaces. “A true Raider fan never leaves.”

Does Frank think I can become a true Raider fan? Sure! “You just gotta find a season ticket holder to sponsor you.” He suggests I come to another game with him, his family watching this exchange in silence. “Take a picture of me and the blond!” he tells a boy.

As I’m talking with a nearby band of tailgaters about the team—it’s one of their birthdays, “We’ll be celebrating the victory, too!”—a couple of women come up with clipboards, asking if we’d like to keep the Raiders in Oakland. They work for Coliseum City, they say, the enormous proposed sports and entertainment complex that is trying desperately to secure funding for a new stadium to convince the Raiders to stay in the Bay Area.

Therein, the rub: the Raiders may not be long for Oakland. The team’s lease at the Coliseum is up at the end of 2015. Coliseum City has struggled to cobble together financial backing, or even the committed support of the Raiders. Los Angeles, the team’s erstwhile home during a 12-year tiff with the City of Oakland over the state of the Coliseum, outdated even then, has been courting the Raiders anew. San Antonio sent an official delegation to meet with Raiders brass in November, and there are whispers that perhaps it will be the Raiders that are shipped off to be the NFL’s anchor team in London. In the stands, fans hold up signs: STAY IN OAKLAND.

I meet two guys, Julian and Ruben, who’ve driven up from L.A. for the game, an annual tradition since the Raiders returned north. Julian gestures around. “This is the most craziest fans ever,” he says.

Back with Vince and his friends, final beers are shotgunned. A woman approaches and asks if anyone needs tickets. We don’t. “Why is it so hard to give away tickets to this game?” she asks no one in particular, wandering away.

The most craziest fans ever begin to make their way into the stadium.

I wish I could say that my first game was a success, that the Raiders broke their losing streak and that I understood what, exactly, was transpiring on the field. Instead, however much I knew about football was not enough, and the Raiders lost, a 24–13 drubbing in which Oakland never led. The man in the seat in front of mine spent the entire game with his head in his hands.

The weeks go by.

The Raiders lose successively to the Browns, Seahawks, Broncos, and Chargers. The team is described as “pathetic,” “lukewarm garbage;” in Week 11, “the quickest team to get knocked out of the playoff race in a decade.” A dead rat is found in the press box and proclaimed “the most Oakland thing ever.” “Oakland Raiders futility rooted deep in team’s culture,” declares Bleacher Report. “Your honest assessment—will the Raiders win a game this season?” asks CSN Bay Area, the local sports network.

Across the Bay, the Giants win the World Series, the victory parade rolling down Market Street.

[pagebreak]

At some point in the midst of this, a Raiders billboard that towered over Highway 580 and to which I’d grown maybe overly attached is taken down and replaced by one for BuzzBallz. There are the two things you need to know about BuzzBallz: 1) they are pre-mixed fruit cocktails sold in fluorescent canisters roughly the size, shape, and psychic effect of hand grenades; and 2) they are the worst thing mankind has ever made.

I begin to have moments of football lucidity. I talk about the season with an Uber driver—a captive and financially incentivized audience, admittedly—and think I trick him into believing I have some idea of what I’m talking about. I blame something on the Tuck Rule—something Vince & Co. wanted to make very sure I understood—and a Raider fan nods heartily. I throw in a “we” every once in a while—as in, “We look good today”—and no one hollers in protest, no silver and black authority jumps out to accost me.

On the 368th day of the Raiders’ losing streak, it pours. It pours in the morning and then lets up a few hours before the game, and then it pours some more. The rain does not care about the Raiders–Chiefs game or about California’s drought. It was the most rain Oakland had gotten in seven months—what constitutes an almighty deluge in this part of the world, maybe the second-most Oakland thing ever.

My phone buzzes. “ARE YOU READY FOR THUNDERSTORM FOOTBALL?!”

I’m not, as it turns out. I realize too late that the only even vaguely waterproof thing I own is a gifted poncho. Not any poncho: a pink poncho covered in Disney princesses and flowers.

It is totally inappropriate: for adulthood, for football, for Raider Nation. I have never been more certain of anything than that I cannot wear this to the Raiders game. I put it in my bag.

Outside the Coliseum with 20 minutes to kickoff, I meet Rob and Devon, who are finishing beers before going in. Rob, who was on my train to the stadium and attracted astoundingly little attention, considering, is wearing a sort of Raiders Soviet officer getup—a long, military-style coat with the Raiders logo stitched onto the back and a matching officer’s cap.

They reveal that they’ve just met: Rob has two season tickets, and the day before had posted on Reddit’s Raiders subreddit asking if anyone wanted to go to the game with him. The only conditions, he said, were that the taker not be crazy, and that he or she buy him a couple of beers. This strikes me as possibly overly trusting—possibly Devon as well, who asks if the Jim Beam and Dr. Pepper combo I offer them (not an advisable mix) has roofies in it, though only after taking a gulp—but it seems to be working out for them.

Devon replied to Rob’s offer immediately, and was granted his spare ticket. Did he have a lot of competition? “I don’t think it’s a very popular subreddit,” Devon says. As proven by that subreddit’s top most-used words of 2014, naturally.

I explain to them what I’m doing there, my quest to join Raider Nation. Rob’s had season tickets for four years, and wants me to understand just how cheap they are. He and Devon discuss it for a minute, and agree that maybe Titans tickets are a little cheaper, but other than that, no one. He likes having the tickets—they’re an excuse to get out of the house, have some drinks, dress up. He thinks I should get my own, that this is the key to becoming a real fan.

Rob is not, however, optimistic about the game ahead of us—not after 16 straight losses stretching from last season, an entire calendar year. He refers to the team as “the poor guys on the field.” “Think about how hard they’ve worked! They’ve devoted their lives to it. And …” He trails off.

“No fan base is as much a part of their team as the Raiders’,” Devon tells me. “They could go 0–35 and everyone would still come out.” Indeed, nearly halfway there, the poor guys will take the field before a sellout crowd. “This is the best fan base in football. I will put that on my grave.” He also offers, as though I’d accused him, that Raider fans are “not stabby.”

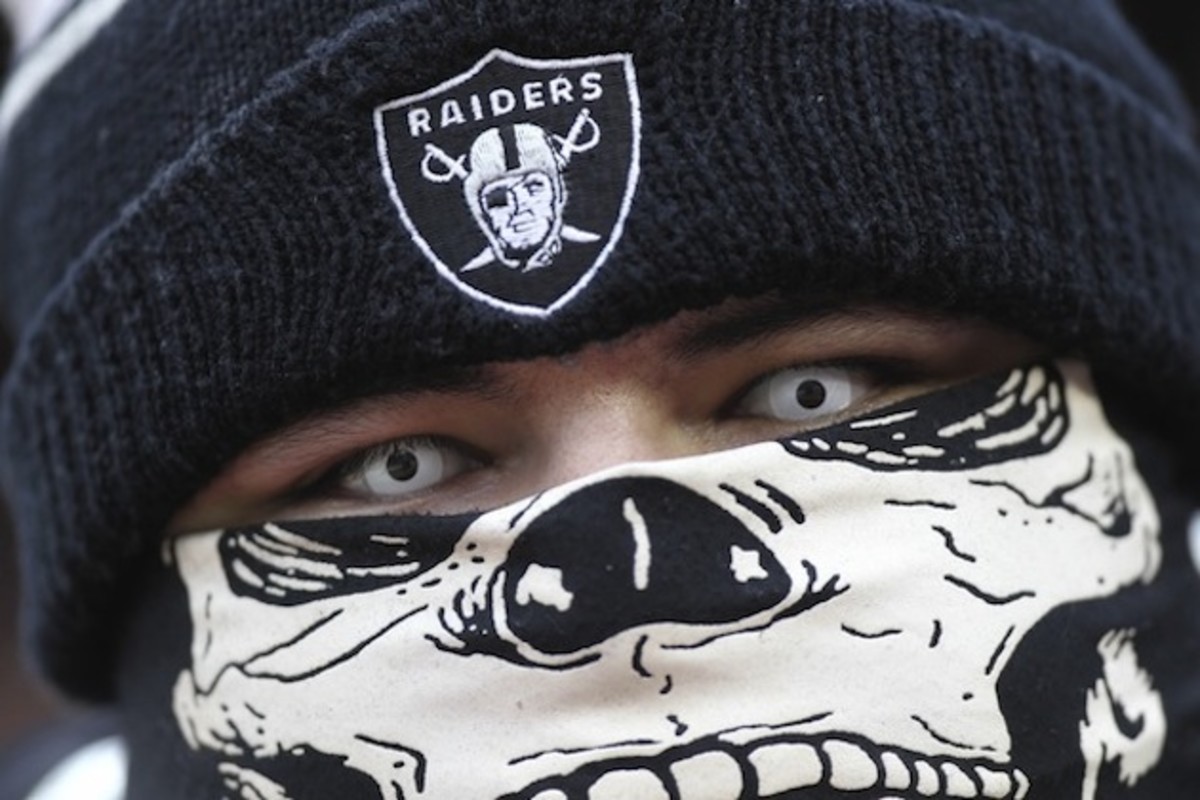

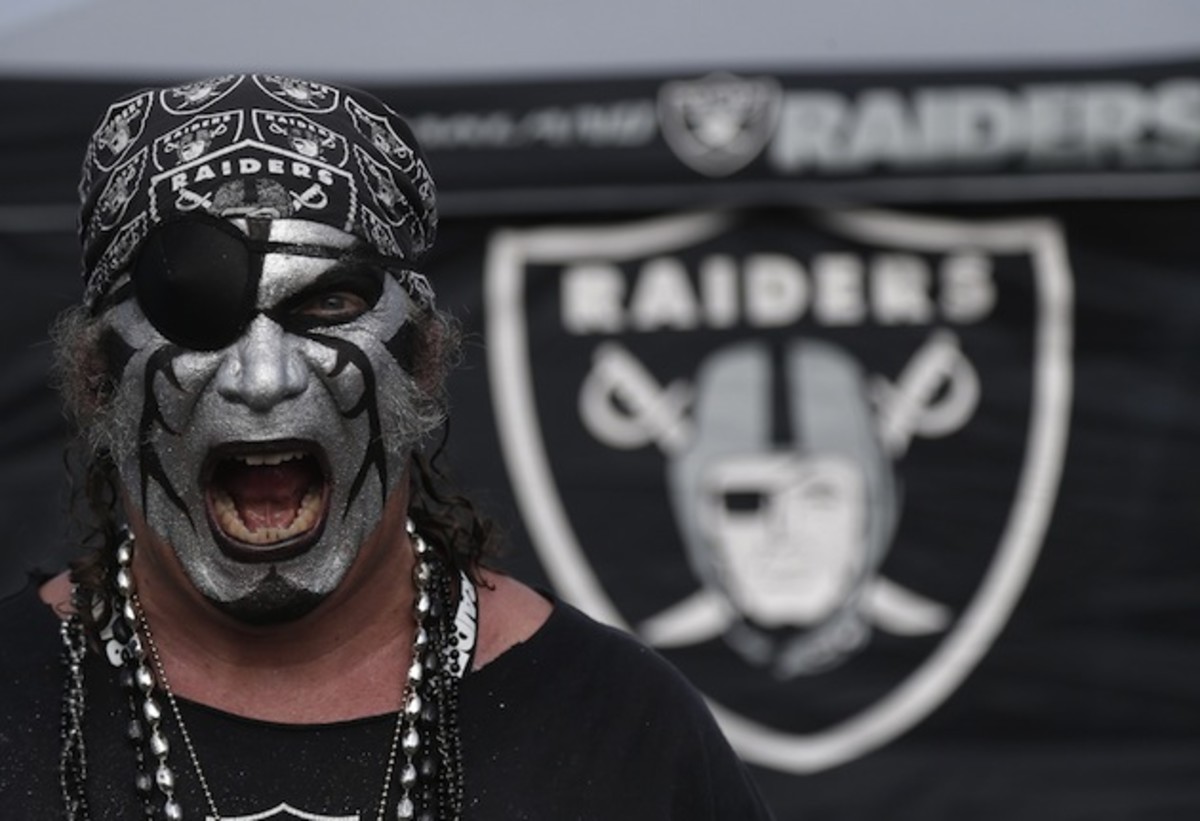

As I wander to my seat, lost in the Coliseum’s endless concrete corridors, hopping puddles and doubling back repeatedly as I hit unexpected partitions, I catch a glimpse of the Black Hole—the section of stands home to Raider Nation’s diehards, the ones in the spiked helmets and face paint and gorilla suits and chains. They’re celebrities in the Nation, patrolling the tailgate before each game and pausing obligingly every 15 feet to pose for a photo—and by pose, I mean really pose, puffing out their chests, lofting their weapon of choice, and snarling, before nodding, blinking their white contacts once or twice, and heading off to the next photo op.

These are the folks people mean when they talk about Raider Nation, Hunter S. Thompson’s mob of thugs and wackos. I see them for just an instant: a sea of silver and black faces, mouths gaping, flashing in and out of view as all of them, every last one of them, fan their arms up and down in rhythm, howling. The screams ricochet down the corridor, so loud it’s impossible to tell if it’s screams or a siren or both.

The rain starts back up, a cold, steady drizzle. Within minutes of sitting down, I’m soaked. It brings back memories of my first—and, until this season, only—NFL game, a frigid, late December Jets–Chargers matchup in which both teams had already been eliminated from the playoffs, and which may, in retrospect, have set the spiritual tone of my football fandom. Finally, shivering, the rain coming down so hard it’s difficult to see, my resistance fails. I pull out the poncho, tugging it over my head in a flash of floral fuchsia, and brace for jeers.

And: nothing happens.

Amazingly, the jeers never come; I am drier, and that is all. Let the record show that for all the talk of whether or not Raider Nation is a stabby place, you can wear a pink, flowery, Disney princess poncho to a Raiders game and go unbothered.

This unexpected goodwill may owe more than a little to the fact that something very different is happening at this game. All of a sudden, the Raiders are up 14–0, looking—even I can tell—dominant. “This is the biggest f***ing lead all season!” someone screams in disbelief behind me.

At halftime, it turns out that the group of ushers in beigey-yellow jackets who’ve been huddled awkwardly by the muddy Raiders sideline the entire game are in reality Raiders Hall of Famers. They’re here, apparently, partly to see former punter Ray Guy awarded his Hall of Fame ring (what appears to be a giant poster of Guy’s face is held horizontally alongside them, visibly soggy), and partly as a desperate PR ploy, to (re-)woo the Oakland powers that be and ward off Los Angeles/San Antonio/London.

It’s raining so hard that when the Raiderettes—Football’s Fabulous Females, the scoreboard announces—jog back onto the field in the third quarter, they’ve changed from their shorts and billowing swashbuckler sleeves into gray tracksuits and white sneakers.

“Take that s*** off!” yells a man in my section.

At the top of the fourth quarter, a woman slides into the seat next to me, draped head to toe in glittering Raiders medallions. She glances at me but doesn’t comment on my choice of waterproofing, cursing at the field and waving her arms while her boyfriend sits meekly on her other side. She is cool, and she will be my way into Raider Nation.

[pagebreak]

I spend the next 10 minutes trying to work out what I can say to her to overcome the effect of the princess poncho. By this point the Raiders had managed to blow the biggest f***ing lead all season; the game is tied 17–17. It does not look good.

“What the hell is that for?!” the girl screams at an ice cream vendor shuffling by our section as we shiver and drip.

“Yeah!” I agree enthusiastically—it’s cold, very cold, and here’s this man trying to sell us Dibs. Doesn’t he know that we’re soaked, that if he could silence the screams and whistles and the roar from the Black Hole below us for one second he’d hear only the rat-tat-tat of chattering teeth and the rustle of sodden ponchos, princess and otherwise? This was it, finally, our chance. Doesn’t he know that the Raiders are being robbed before our eyes, that one sacred W stolen away by a team awash in them? What the hell is that for?

I turn excitedly, knowing that I have finally broken through, that now we’ll talk all quarter and she’ll invite me to a secret Raiders bar after the game, where we’ll drink from Raider cups and she’ll give me one of her Raider medallions and I will be inducted, finally, into the Nation, and it is then, beaming expectantly at her in joy for our time to come, that I realize she was talking about something on the field, and not about the ice cream at all.

It’s still 17–17. Then Kansas City gets a field goal, and the Raiders, who’d been so far ahead, slip behind. But then: Carr throws, and Jones, he of the double fumble, catches. Touchdown.

Suddenly, I’m on my feet. And then it’s the best part of the game, the part I still don’t really understand but love anyway, when winner and loser reach some unspoken agreement and decide the score isn’t going to change any more as the clock slowly runs down, and all the action suddenly straightens up and slows, players winding calmly, politely around one another, all the rigid lines of the last four quarters broken, teammates hopping up and down at the side of the field, clutching each other. This time, for the first time this season, for the first time in a year and three days, for the first time since I tried to clamber aboard, it’s the Raiders hopping and grabbing each other: We did it!

We scream. We all scream. The pink poncho flops around me, drops flying. A boy in front of me reaches back for high fives, and I give him one. Marcel Reece dives into the Black Hole and the screams get even louder. The Raiders win.

Eventually, we start to wind our way out of the Coliseum, and everywhere the chanting is the same: RAIDERS! RAIDERS!

Outside the Coliseum, the rain has let up, and a dance party breaks out. Someone is blasting “Get Low,” and a crowd gathers, bobbing triumphantly. A sign is flashed: JUST WIN ONE, BABY, which they have, now, won one, maybe only one, but they did it. Someone tapes a man a few sections over from mine screaming that the Raiders just won the Super Bowl.

I see a man in a floor-length leather jacket, long braids and a silver and black fedora atop a gleaming silver mask shaped like a skull, sinew clinging to its sides. I ask if I can take a picture with him, pushing pink flowers aside to shake his hand.

“You see the bird?” he asks. A seagull landed on the field at the start of the fourth quarter, scuttling to and fro but mostly ignoring the action—Chiefs touchdown, Chiefs field goal, and, finally, that last Raiders touchdown that ended 368 days of waiting. Yes, I saw the bird. I can’t see his face through the mask, but I imagine him beaming behind it, eyes agog.

“That was Al Davis, baby,” he says.

Al Davis: Legendary owner and GM (for the 45 years beginning in 1966); legendary jerk (for the 82 years beginning with his birth); coiner of the “Just Win, Baby” mantra and the by-any-means strategies that followed; founder, essentially, of Raider Nation. Earlier, I saw a portrait of him hanging in the Black Hole-residents-only tailgate bar pitched in the parking lot—the beady-eyed patron saint of Raider fandom. The man in the skull mask stalks off, deeper into the parking lot, unopened Heineken in his skeletal glove.

In the long line across the barbed wire-rimmed BART walkway from the stadium, all of us pressed soggily against one another, shuffling forward inch by inch, I hear a little boy’s voice: “The Raiders won,” he says quietly. I turn back to look for him, but he’s somewhere behind an impenetrable line of huge, silver and black bodies. All I can see are two little shoes, Velcro straps done up tight, marching forward between so many giant feet, little step by little step.

I wonder what he’s doing walking, why he’s not being carried by whichever giants are his, but then I think, maybe he wants to walk. Maybe the Raiders’ fallow year—fallow years, if we’re being honest, having won fewer than a quarter of their games since 2011—gave him time to grow up a little more, to learn about the team, to figure out exactly what it is that he’s watching. Maybe this is his first Raiders victory, too.

They did not win the next game. In fact, they were killed: picks, fumbles, 52–0, their most lopsided loss in 53 years. Midway through the carnage, the San Francisco Chronicle’s beat reporter summed things up:

28-0 #Raiders down with 11:14 left in the first half. Sure looks like getting the one win was all the players were interested in

— Vic Tafur (@VicTafur) November 30, 2014

But when the Raiders beat the 49ers a week later, winning in three weeks as many games as they had won in the preceding 58, the players dumped Gatorade over Tony Sparano (Soprano).

I hadn’t, until that point, bought any Raiders gear. It seemed too easy to buy something and melt into the crowd that way. I wore gray and black, but nothing with the Raiders logo, a Rubicon with fans on one side and the indifferent or otherwise aligned on the other.

That night, at 2–11, tied for last place in the league and on their way to a 3–13 record, the team’s second-worst season in half a century, I bought a Raiders shirt.

Oaktooownnn, the calls will come from the shadows.

And now I understand.

A version of this column originally ran at The Cauldron on Medium.com.