What I learned from failing in Las Vegas on American Ninja Warrior

It sucks to fail.

I want to say that it wasn’t my fault, that the rope ladder was slippery and waterlogged. I know that’s true, but I also know that the competitors directly before and after me grabbed it easily. If I’d let go of the Big Dipper a quarter second earlier, I could’ve swung higher and done the same as them. So even now, two months later, if asked how I feel about my performance on “Ninja Warrior,” I’d give the same answer I gave that night when I climbed out of the safety pool, skulking along the sidelines, dripping wet, the cameras following behind me: disappointed.

Driving down to Kansas City to compete, I had told myself that I would be satisfied just to make it to the city finals. It was my rookie year, and I’d already started to burn out from the two-plus hours of training every day, anyway. From constantly obsessing about what the course obstacles might be to renouncing beer and pizza and sour cream, I was at the end of my proverbial rope. When I arrived at the hotel that night, I refused to do my nightly routine of stretching and foam rolling; it was my great act of defiance.

The next day, I did what I set out to do and climbed to the top of the Warped Wall.

I smiled as the crowd cheered. And I smiled as their cheers faded. And I smiled still. “This guy really doesn’t wanna leave!” I heard Matt Iseman say, after which I finally climbed down the stairs. At the bottom, my dad and brother hugged me, and a producer gave me instructions that I had to ask her three times to repeat. She was directing me to the Winners’ Circle, a collection of folding chairs next to the Warped Wall reserved for everyone who’d completed the course.

Joining the other finishers was like sitting down at a cousin’s wedding: everyone looked familiar and was ready to celebrate. Earlier in the day, my brother had pointed out Meagan Martin — “Dude, that’s one of the best climbers in the world!” — so I sat down next to her. Like the other veterans, she was casual, relaxed, unsurprised by her success.

“Vegas is so much fun,” she told me, “you just get to hang out and train for five days.” The guy next to her nodded and took a bite of a candy bar. That’s when I realized I hadn’t eaten in six hours, and reached for my unopened bag of snacks before watching the rest of the night’s competitors. When they’d slip on the Hanging Tiles or fall off the Ring Toss, I’d shrug: Better luck next year, guys.

The following day, as they showed us the four new obstacles on the finals course, I remembered what Meagan had said about Vegas. I dreaded the thought of more ripped calluses and sore elbows and meals without pizza, but when I saw them, I knew I could climb the Salmon Ladder, lache across the Flying Shelf Grab, and cruise through the Body Prop if I used my legs well. For the Invisible Ladder, I’d either make it to the top or die of heart failure trying.

I started to warm up.

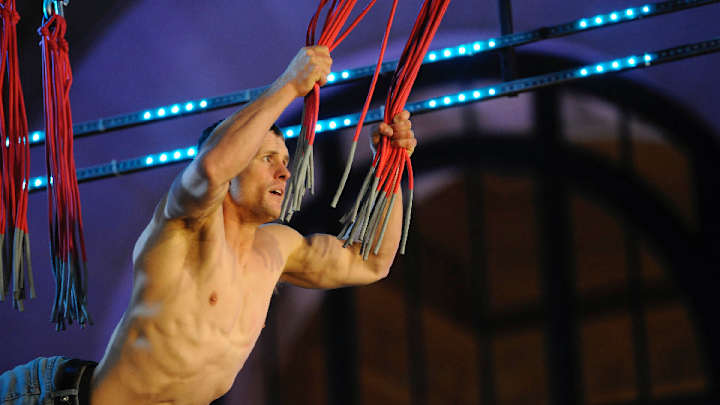

The second time around, my anxiety was less debilitating. I was still pacing and spontaneously breaking into five-meter sprints while I waited, but I’d stopped picturing myself collapsing into the water at the start line. Eventually, the producer gave me the cue, I heard the gong, and took the Q-steps somewhat awkwardly. I was thinking about how I’d run the Hanging Tiles when I unlatched the bar for the Big Dipper. Then I swung and released too late. As I grabbed it, the ladder jerked down, and I felt my toe touch the water. The lights on the course flashed red, I struggled to get my feet on the platform, and backflipped off into the water, knowing that as soon as I surfaced, someone behind a camera was going to ask me how I felt about failing on the second obstacle.

When I checked in with the producer at the Winners’ Circle, I looked dejected enough that someone in the stands yelled, “You did great, man!” I kept my head down. Since I was the 11th ninja to run, and 15 would go through to Vegas, I needed to wait around until I was bumped out of the qualifying bracket. I grabbed my bag and changed inside of Union Station. Coming out, I found a group of high schoolers in tuxes and evening gowns standing in the lobby, staring through the windows at the course. “Your prom must not be very fun,” I thought as I pushed my way through. One of them shouted after me: “Hey dude, how’d you do?”

After I sat down and the adrenaline wore off, I noticed that my fingers hurt. I put them in ice, but still, they hurt, as if all the pain that I would’ve endured while training for Vegas had been condensed and channeled into my hands. Embarrassed to be both injured and a loser, I asked the producer to see a medic. I wanted him to tell me that I’d compound fractured three fingers, that it was miraculous I hadn’t gone into shock from the pain. “Open your hand,” he instructed. “Close your first. Does this hurt? They’re just bruised. You’re fine.”

“I’d rather have ripped calluses and sore elbows,” I said to myself as I sat down again. Then, I saw Meagan, who had gone to Vegas the previous season. She was soaking wet; the Big Dipper had defeated her, too, which made me feel slightly better.

Eventually, I was bumped out of the top 15. I thanked the producers, congratulated those who had finished, and left with my dad and brother to go find pizza.

When the Kansas City qualifier aired in May, I invited everyone I knew to a bar on my block and hooted and hollered when my name flashed on the final leaderboard at No. 17. “Faster than Brian Arnold,” I screamed. “No big deal.” Beaming, I accepted all of my friends’ congratulations because I knew that I was a phony. In six weeks, when the city finals episode aired, my honeymoon would end. I’d be found out.

A week ago, I call Meagan, ostensibly to get another perspective on the course. She was coaching her kids at the Youth National Championships in Atlanta, so we chatted about the similarities between climbing competitions and “American Ninja Warrior.” Both give you only one shot, she said.

Then, I asked her about the Big Dipper. “It was soaking wet!” she said and laughed. “It didn’t fly the same at all!” I nodded enthusiastically. “I remember kicking off, and I’m like, ‘Hmmm, this is weird. Oh no. I’m actually not picking up any speed. Oh no! Oh no!’ And I try to jump even though I have no momentum, and then I’m in the water.” This is essentially what I expected to hear, so I asked her the question that I really called to ask: “How did you handle the disappointment of failing?”

A pink slip from the Giants? I've faced worse than being cut by an NFL team

“What happened ...” she paused for a second and started over. “I don’t know what I could’ve done differently. So, I almost…” Another pause, and then she found her stride. “What I tell my kids all the time is: Just do your best. And I think I did do my best. I think what happened was kind of random, but it wasn’t from lack of trying or lack of being smart about it. It just happened, and there was nothing I could do.”

Competing on American Ninja Warrior requires a certain level of comfort with the unpredictable. After prospective ninjas send in their audition tapes, they wait for months and find out if they’ll compete just four weeks beforehand. They don’t know what the obstacles will be, where in the order they’ll compete, or if it’s going to rain. Because so much is unknown ahead of time, it’s easy to make a disastrous slip. For many, months of training end with a misplaced step or an errant toe. For a veteran like Meagan (or Brent Steffensen or Kacy Catanzaro or Flip Rodriguez), disappointment is the rule, not the exception.

Meagan takes little solace when fellow champions flop. “I don’t ever compare myself to people on other courses because we weren’t on those obstacles. Things can happen, even if you’re technically supposed to be good at something. Like, you could still fall.” I wish I were as magnanimous. Seeing NFL kickers, Olympic runners, and four-year ANW veterans fail helped me pretend that others’ gaffes were more glaring than mine, that I was the only ninja who succumbed to bad luck. That’s the seductive thing about American Ninja Warrior — the fatal mistakes are so minor, so seemingly capricious that victory always seems within reach. It’s easy to believe that on Season Eight, I’ll easily mount the rope ladder.

When I asked Meagan if she’ll compete again, she said that she has unfinished business now. “Each time I’m becoming a little more addicted. I have to complete the city finals course next year. And I have to complete Stage One in Vegas. And Stage Two and Three and Four.” She wants to train more to prepare. Maybe she’ll skip a climbing competition and fly out to California to get on some obstacles there. I said that I wished she would coach me, and she said we could plan a session if I really wanted.

We both laughed and made plans to meet at the top of Mt. Midoriyama next year — as long as it doesn’t rain beforehand.

(This story by Spenser Mestel was originally published at The Cauldron on Medium.com)