A high we have to have: On football, concussions and accepting the past

Football always seems to sneak up on me, somehow, and before I even realize, it’s happening. I’m 47 now. The early-August two-a-days of the late 1980s have disappeared into the past. Truth told, I’ve done everything I can do to put them out of my mind. I wish it were that simple.

Meanwhile, the masses once again spend their weekends entering the coliseums (or, barring that, tuning in to College Gameday). Are they not entertained? Of course they are—we always are.

Not me. As baseball winds down and America’s addiction to football peaks yet again, a growing part of me wishes summer would never end. I didn’t always feel this way, and anyway it’s a strange confession to have to make—that I don’t love football anymore. Truthfully, my animosity towards the game came on gradually, over a period of years, hardening and hardening until I finally started coming to grips with the ugly truth.

But to understand how and why I arrived here, you first need to know where I’m coming from.

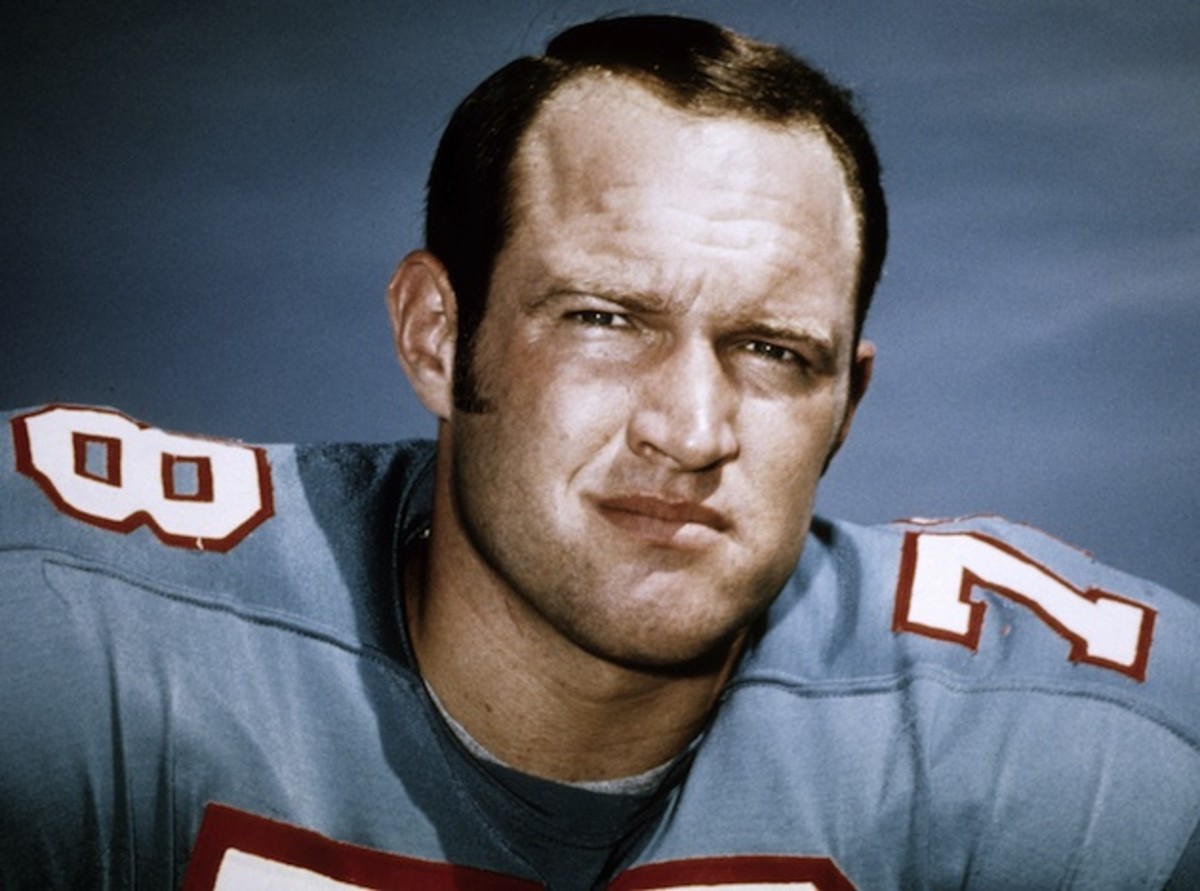

We might as well start here: From the outside looking in, you could say football has been very good to me. My father was an All-America in college and an All-Pro in the AFL, playing eight full seasons (including four in the NFL) and never missing a game. As for me, I earned a scholarship to an outstanding academic school in Division I, and had my undergraduate education paid for in full. I made lifelong friends through playing football, and a big part of me still misses that feeling of fraternity. In fact, it’s probably one of the biggest reasons why I decided to pursue a career in the military. There, I made an even greater group of friends. To this day, I cherish the memories of playing in front of 70,000 fans, of the the victories we earned.

Football was good to my father and me. No question about it.

That’s one side. But there’s another side — the collateral consequences, many of them negative, that didn’t reveal themselves until later in our lives. It’s not fair for me to speak too much for my father. He was never one to talk about his injuries, let alone how he felt. He played offensive tackle for nearly a decade, hitting and being hit on every offensive play. If I had to venture a guess, I’d say he’s had his head hit thousands of times—if not tens of thousands. Like many of his peers, he now has cognitive dysfunction.

Leonard Marshall on CTE, Concussion, and the NFL then and now

I suffered a number of concussions, and played on anyway. Back then, even when you got your bell viciously rung, you kept playing. It’s what we did. If it was really bad, as it was following my most significant hit (we'll get to that), you went into the locker room and were held out for a week—maybe. But no one thought concussions could cause permanent brain damage, or that numerous concussions and even sub-concussive hits to the head could do the same.

They were never a serious issue, and it may well have stayed that way if not for a Nigerian-born pathologist named Bennet Omalu. It was Dr. Omalu who was on call the day former Mike Webster’s body was brought in for an autopsy. Omalu noticed that Webster, the Hall of Fame center for the Pittsburgh Steelers who’d died at the age of 50, looked more like a man 20 years his senior. Puzzled, Omalu decided to examine Webster’s brain. While the brain appeared normal on the outside, a closer look showed something far different: abnormalities typically associated with Alzheimer’s patients. This new disease was named Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), and Omalu would eventually find it in the brains of former Steelers Terry Long — who’d committed suicide by drinking anti-freeze — and Justin Strzelczyk, killed in a fiery car crash after leading police on a high-speed chase.

Researchers have since examined the brain tissue of 128 football players, all of whom had played the game professionally, semi-professionally, in college or in high school. Within that sample, 101 players, or just under 80%, tested positive for CTE, which develops when repetitive head trauma produces abnormal proteins in the brain. These proteins work to essentially form tangles around the brain’s blood vessels, interrupting normal functioning and eventually killing the nerve cells themselves. Patients with less advanced forms of the disease can suffer from mood disorders, such as depression and bouts of rage, while those with more severe cases can experience confusion, memory loss and — in some cases — advanced dementia.

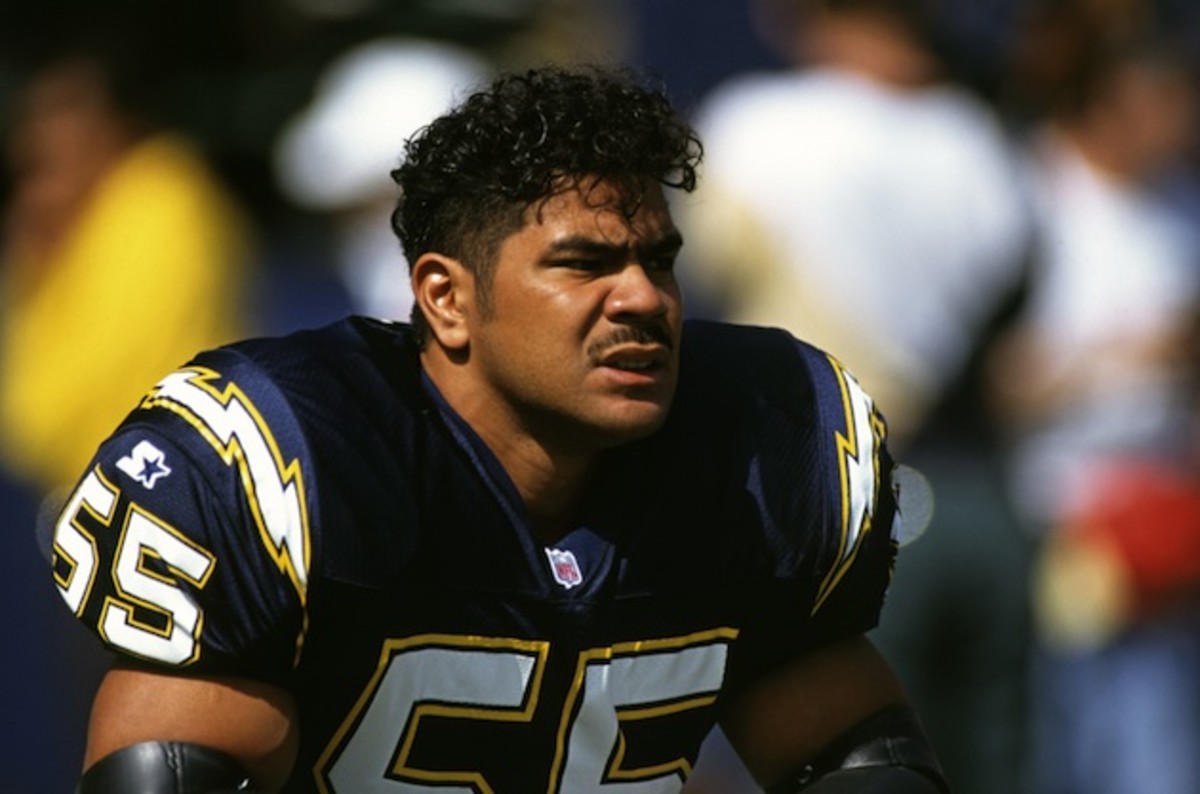

NFL players found to have had CTE include former Chicago Bear Dave Duerson and San Diego Chargers legend Junior Seau, both of whom eventually committed suicide. Jovan Belcher, the former Kansas City Chiefs linebacker who shot and killed his girlfriend before taking his own life, was also determined to have CTE.

Leigh Steinberg, former agent for numerous NFL quarterbacks, recounts the conversation he had with Troy Aikman hours after the Dallas Cowboys won the 1994 NFC Championship, during which the star quarterback suffered a concussion:

Aikman: Where am I?

Steinberg: You’re in the hospital.

Aikman: Did I play today?

Steinberg: Yes, you did.

Aikman: How well did I play?

Steinberg: You played very well.

Aikman: Did we win?

Steinberg: Yes, you did.

Aikman: What does this mean?

Steinberg: It means you’re going to the Super Bowl.

Five minutes later, Aikman asked the same exact questions, and Steinberg gave the same answers. After another 10 minutes had passed, Aikman and Steinberg had the same conversation again.

Perhaps the most shocking discovery made by doctors, however, has been the frequency of CTE in college and high school players — including one 18-year-old prep player who died following his fourth concussion, leading researchers to conclude that CTE can begin in youth football players.

It's time for Saints to move on from magic of the past and look forward

I’m certain I suffered concussions that went undocumented during my youth football days, but it wasn’t until college that I experienced a hit which I can now point to as being the turning point.

It was 1989, and Arkansas, where I was playing at the time, was taking on Baylor in a late November game. With just a few minutes remaining in the fourth quarter, I went out and lined up with the kicking team. My role was to be a “safety,” one of the players whose job it was to hang back and make a tackle only if the return man beat the coverage.

That’s exactly what happened. After their return team opened a huge gap, the runner was heading full speed straight at me. At first, I thought the best approach would be to simply get in his way. Then, at the last second, realizing I was flat-footed and in danger of being run clean over, I ducked and tried to body-block him at the legs. As he went over me, his knee struck the right-back side of my head. Down he went. I’d made the touchdown-saving tackle.

I also was knocked unconscious. When I opened my eyes moments later, I found myself lying face down on the turf. For an instant, I didn’t know where I was. Then, suddenly, I was back. I pushed up and off the turf, only to realize one of the officials had me by the arm. I quickly turned towards our bench, ready to run off the field. The first step I took was with my left foot. As soon as it hit the ground, the weight of my body collapsed on top of it, and I fell back down. “That’s weird,” I thought before standing back up once again. This time I limped off, dragging my left foot in tow because it wouldn’t answer the commands my brain was sending. It took everything I had just to get myself off the field. Looking back, watching replays of the televised game, it’s almost fun, seeing the trainer meet me halfway to the bench and taking me by the arm. They started evaluating me almost immediately, and even took my helmet away — at the time, the only tried and true method of preventing a player from re-entering the game.

Blanket Coverage: Rodgers vs. Brady and an O-lineman’s toughest job

Shortly thereafter they took me to the training room for further evaluation. I can still remember watching the rest of the game on the locker-room TV, although the memory has always been a fuzzy one. It was somewhat surreal, seeing something happen on the screen and then hearing the real-time roar of 55,000 fans. I remember calling my parents, watching back in Texas, and telling them I was alright. I also recall the trainer telling me not to go to sleep, and to have my roommates wake me up every two hours — just in case. I’d been officially diagnosed with a concussion, which was soon reported in the media.

I was listed as probable for the next game.

The next week was a kind of waking dream. I went to practice, but didn’t participate. I went to my classes, but it all made me feel scatter-brained. More than anything, I was tired. But come game time the following week, I was sure I was ready.

I’m convinced I sustained another concussion the following season — on a very similar play, no less. Only this one didn’t affect me like the previous one, mostly because I was able to get up and off the field on my own power. I wasn’t taken out of the game, even though I felt the same, spacy symptoms. I just didn’t tell anyone. I wouldn’t miss a single practice or game the rest of the year.

My football career ended at 23. I went on with my life. Then, when I reached my thirties, I started noticing things. For no discernible reason, at the most random times, I‘d experience intense episodes of sadness, guilt or self-criticism. Spring or fall, summer or winter, the attacks didn’t discriminate. They came without warning, and would often strike on days when I otherwise felt completely normal. Unlike many who’ve been diagnosed with CTE, I’ve never had thoughts of harming myself; it wasn’t like that. It was more a general feeling of uneasiness, of being angered or annoyed, but without any discernible or precipitating event I could peg it to.

I know now these symptoms are consistent with what we’re now seeing in victims of head trauma — not just in football, but in hockey and even soccer, as well. Are these experiences the result of concussions or repetitive head trauma? It’s hard to say. At the same time, it’s telling that I only began having these bouts after suffering my concussions. I wasn’t depressed as a kid. I wasn’t depressed in college. With time, I’ve grown to feel fortunate to see these episodes for what they are — that I’ve been able to control them, for the most part, through sheer force of will and logic. But they still manage to find me, often on an otherwise perfect day, for no reason at all. Or no reason I care to grant any power more potent than my own willpower.

Today, as I hear about more and more kids suffering concussions and catastrophic, often life-changing injuries, I start to wonder if it’s really worth it. Football is a great game — a beautiful game in so many ways — and we, as Americans, have grown to love it. But the price some pay, physically as well as psychologically, is just too much. That might be just one man’s opinion, but it’s not based on nothing.

I have two sons. Neither of them has ever played a single down of football. Baseball, basketball, track, soccer — they love them all. I never suggested football to them, and they never asked. I wasn’t about to be one of those dads who puts a ball in the crib and takes them out to throw and catch as soon as they’re old enough to walk. Had they approached me about playing football, I’d have talked to them about it. I might have even allowed them to play. At the same time, I’m thankful they never expressed an interest in it, and I’m relieved they never played.

I confess that I, on occasion, and like so many others, will break down and watch football. I know I’m feeding the beast. Because somewhere deep down, football appeals to something dark and innate, and yet beautiful in its precision, teamwork and community. It’s something you just can’t get from basketball, baseball, hockey, or anything else — something uniquely American. It’s a high we have to have, if only so we can continue avoiding talking about the consequences.