The umpires strike back: An expanding strike zone is hurting baseball

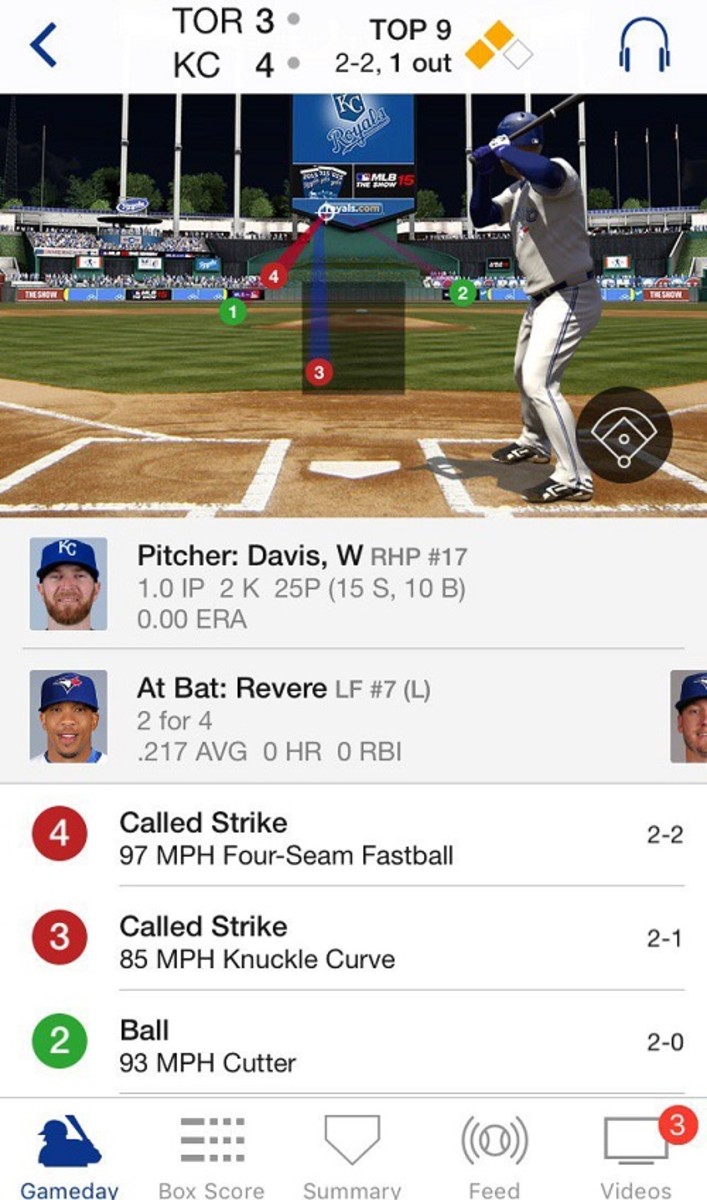

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away (i.e. in the ALCS in Kansas City), Ben Revere took his place in the batter’s box — his team trailing by a run and down to its final two outs — and tried to be a hero. Though slight (5'9", 170 pounds) and utterly devoid of “force” (four career homers in 2,660 plate appearances), virtually any ball put in play would’ve gotten the job done.

With men on second and third, the Blue Jays seemed to have destiny firmly in their grasp ... until home-plate umpire Jeff Nelson snatched it away, like some weird parent scarfing down his kids’ Halloween candy while they’re asleep.

Revere took the first two Wade Davis pitches for balls, before letting a near-perfect strike zing over the plate. Another ball brought the count to 3–1 — a hitter’s dream in almost any instance, and particularly one as high-stakes as this was.

Except ...

Steeee-rike!

Bruh ...

Anyone watching the game could clearly see that strike two was actually ball three, high and outside as they come. So, instead of awaiting whatever down-the-pipe meatball came next, Revere — now facing 2–2 — was forced to play defense in the batter’s box. In this case, that meant whiffing on a pitch down and in.

He did, however, make contact just moments later.

Admittedly, had Josh Donaldson knocked in a run or two in the following at-bat, Nelson’s terrible call would’ve been a mere footnote. Instead, the likely AL MVP grounded out to end the series, sending the Royals to their second consecutive Fall Classic (where they toppled the Mets in five games) and rendering Revere’s second called strike an injustice that won’t get much attention in the grand scheme of things. Maybe Revere would’ve struck out anyway, but at least the out would’ve been his to make.

Are we risking sour grapes by blaming a single call for the outcome of a game? Sure, but at the same time, there’s little denying how significantly the call impacted Revere’s approach, and thus the likelihood of him authoring a successful at-bat.

For his career, the Toronto outfielder has hit .333 (39 for 117) with 59 walks in 3–1 counts. By contrast, Revere is batting .279 (111 for 397) with only 31 walks after getting into a 2–2 count. And while that latter figure is much better than the average hitter (.193), it still represents a 54-point drop. According to Ryan Fagan of The Sporting News, the MLB batting average in a 3–1 count is .274, with an OPS of 1.029. When the count goes to 2–2, those marks drop to .193 and .584, respectively. Obviously, a single call (in the right circumstance) can and will direct the course of a game.

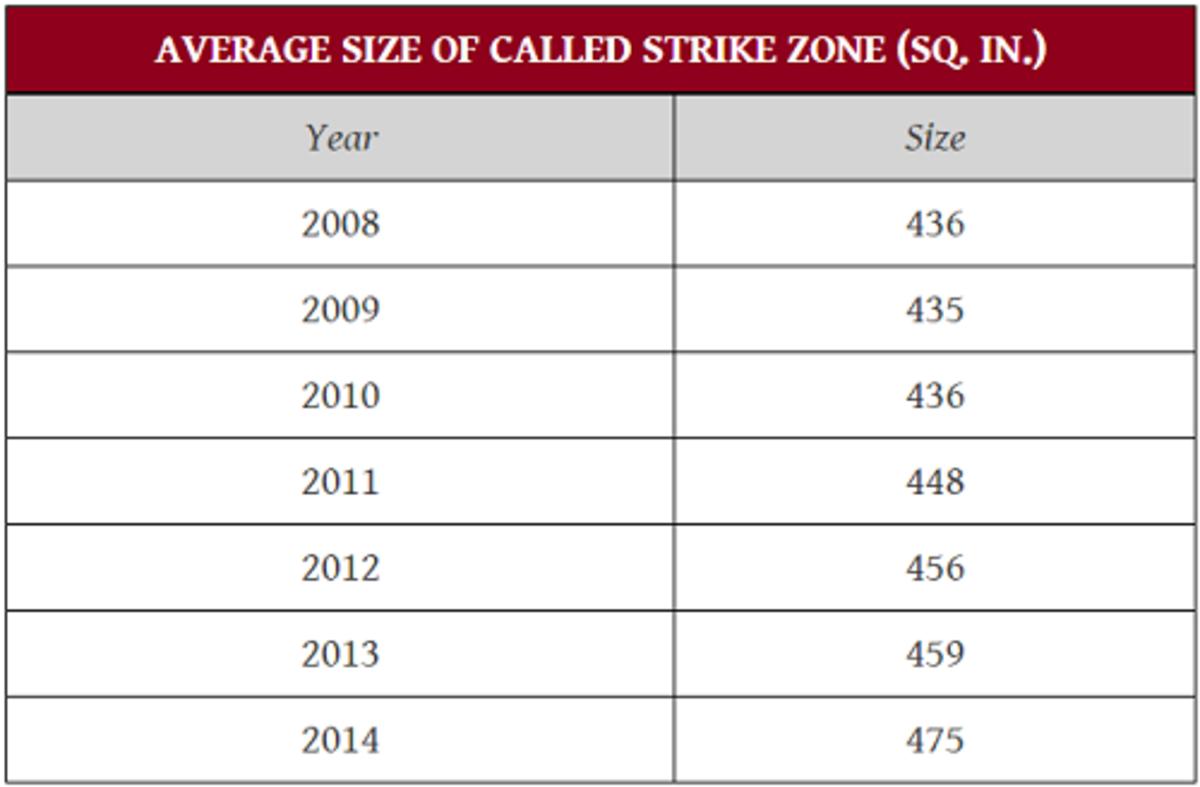

Ultimately, however, this isn’t about a single aberrant call in a single game (albeit a hugely pivotal one). In fact, the strike zone has been a pretty serious issue for Major League Baseball for some time, having grown by nearly 40 square inches in the previous six years alone, according to a Hardball Times article by Jon Roegele.

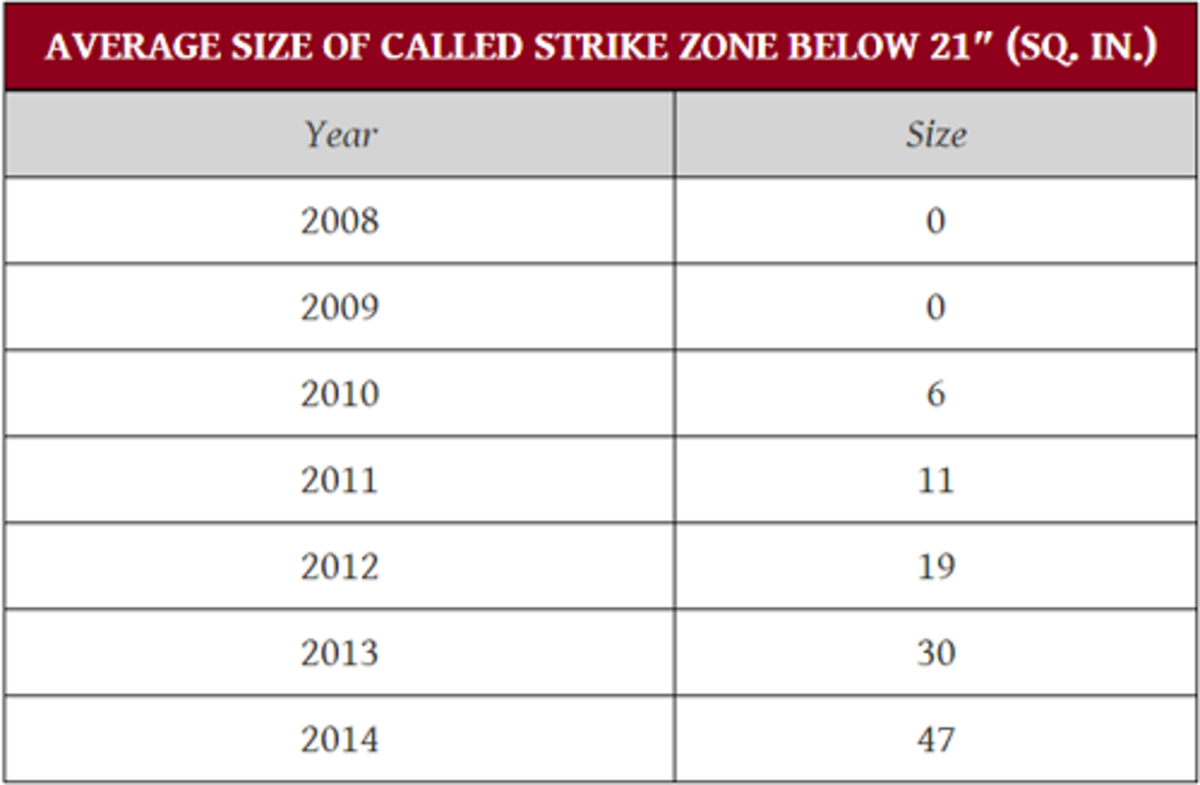

Expanding the strike zone — deliberately or tacitly — is one thing. But what’s really hurting the game is where called strikes are expanding to. In this context, the Revere pitch was actually an outlier, standing in contrast to its bottom-of-the-zone brethren.

The data is clear: Nearly 10% of the (expanded) strike zone now sits below 21 inches. That’s alarming. Crazier still, the growth of the zone in the area below 21 inches is 21% larger, in terms of square inches, than the overall growth of the entire strike zone.

If for some reason you don’t believe that, you probably didn’t watch this year’s NLDS.

The low end of the strike zone has dropped three inches in total, from 21 to 18. That doesn’t seem like too big a deal, right? I mean, we’re only talking a Three-Hour Energy below the knees. But when that relatively tiny space encroaches upon an area hitters already find inhospitable, that the differences become noticeable.

Per Roegele:

Previously I’ve shown that pitchers have been throwing to this expanding band at the bottom of the zone more and more each season to take advantage of the new pitcher-friendly area, and in turn hitters are now swinging more at pitches in this region. This is a trend that continued in 2014.

I updated the calculations for this past season using the same technique as I used before, which involves using wOBA constants to calculate the expected run difference by count for the next pitch being a strike as well as the next pitch being a ball and summing up these tiny run differences over all instances of called pitches to the regions where the strike zone has been changing most notably.

Basically that means that we’ve seen a 43% drop in expected runs from 2008 to 2014 over virtually the same number of total pitches (129,593 to 125,599 — a 3% difference). This only takes called strikes into account; in another chart available in Roegele’s article, he shows that hitters are actually starting to swing at a higher percentage of lower pitches as well. Like Ben Revere taking a bad called strike and being then forced to protect by swinging at a low one. Revere’s at-bat was just one glaring example a legitimate wider issue, so perhaps the gravity of the moment will finally spur the league to make some changes.

For his part, commissioner Rob Manfred has been vocal about trying to get the calls right when it comes to the strike zone, and baseball does (supposedly) have a remediation process in place for scofflaws. Still, seldom have we encountered an umpire guffaw more galvanizing than what befell Revere and the Jays — one that could prove the critical mass necessary to addressing the efficacy of the status quo.

Still not convinced that this is an problem? Check out Daren Willman’s work over at baseballsavant.com to compare pitches thrown outside the strike zone for each season since 2008. Or look at the chart below:

Those blue bars look nearly identical. With a variation of only 17,000 pitches or so (approximately 4%), the total number of pitches thrown outside the zone has remained relatively consistent.

You know what else is consistent? The bad calls! To be fair, the calls were actually “worse” in ’08, but that can be attributed to the relatively smaller strike zone. As the zone has grown (again, 10% of it is below 21"), the number of called strikes outside it has gone down (11% fewer called strikes in ’15 as compared to ‘08).

Basically, by increasing the size of the zone, umpires have made themselves look better (sort of?), thereby sparing them the kind of all-eyes scorn that’s made for the occasional PR nightmare in the NFL and NBA, where referee influence is much more prominent.

So what is the solution, beyond commissioning a fleet of protocol droids fluent in more than six million forms of communication? Unlike many of my pro-robot peers, I’m not so sure that dehumanizing the game is the answer. One thing for which I’ve advocated in the past — and that I believe would be easy enough to implement with relative speed and ease — is eyewear equipped with a heads-up, real-time strike zone display. That way, we could work to clean up the zone’s inherent subjectivity without removing completely the institutional role of a fallible umpire.

Or we could just have Darth Vader cut off the strike-calling hands of those who most grievously abuse the zone. Look how it motivated Luke Skywalker!

That may be taking it a bit too far, but some form of punishment — or recourse, at least — needs to be put in place.

Whatever Manfred and Co. decide to do, let’s hope it leads to a day when we don’t have to worry about watching another playoff game hinge on a blown strike call. Because I know a few million fans who’ve seen one too many of those.

(Contributed to The Cauldron by Evan Altman.)