For Jeff Samardzija, it's been a huge risk going all in for a big payday

While there are myriad nuanced options open to him, the gambler really has but two choices: bet or fold. You can’t win anything if you don’t bet. Then again, you can’t lose anything, either.

Jeff Samardzija has never been afraid to bet on himself. But as he stood on the mound at U.S. Cellular Field on Sept. 15 of last season, trademark long locks hanging about his neck in sweaty clumps, the man they call Shark was feeling like anything but.

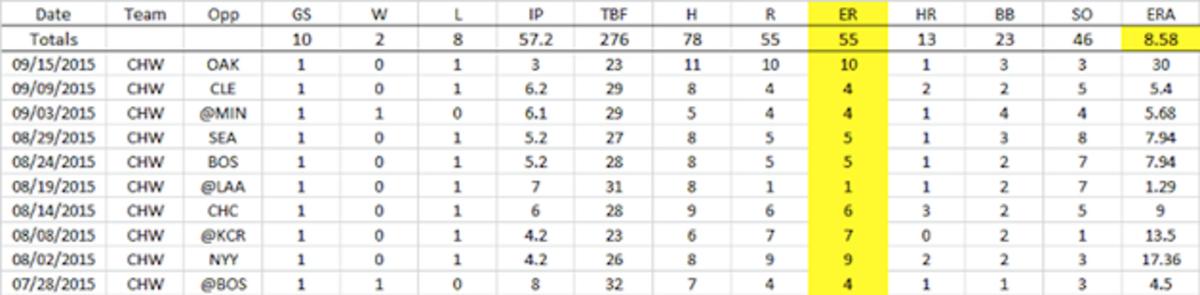

He’d already been out there for quite some time. The Oakland A’s had just pushed across their 10th run of the game — all of them earned — and it was only the third inning. Samardzija had been left to take the beating like a punch-drunk tomato can, a role with which he had become all too familiar. (That short outing marked the nadir of a 10-game stretch in which he had allowed 55[!] earned runs.)

To put that in perspective, Jake Arrieta — his former Cubs teammate — allowed only 45 earned runs in 33 starts. That’s a whole season.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this.

As a three-sport star at Valparaiso High (less than an hour’s drive from Chicago), the 6-foot-4 Samardzija excelled at anything that involved a stick or a ball. He lettered in basketball, and was first-team All-State as a senior hurler. But it was on the gridiron where he truly stood out, earning first-team All-State honors three times, and finishing second in Indiana’s Mr. Football voting to fellow future Major League pitcher Clayton Richard.

Samardzija went on to Notre Dame, where he played both baseball and football. In his final two seasons, the lanky wideout reeled in 165 passes for 2,232 yards and 27 touchdowns, tufts of hair fluttering beneath his golden dome all the while.

Thing is, Shark’s arm was at least as good as his hands. As such, the Cubs’ Jim Hendry saw fit to make sure Samardzija traded his wide receiver gloves for a baseball mitt, offering him a five-year deal with a no-trade clause — a Hendry staple — and club options that could push the value of the contract as high as $16.5 million.

Guaranteed money in a sport with less injury risk and greater career longevity? You might as well ask if you want to double on that 10 when the dealer’s showing a 6.

Samardzija made his Major League debut (as a reliever) in July 2008, taking Kerry Wood’s roster place when the oft-injured fireballer made a trip to the DL. Green-and-gold Cubs shirseys were everywhere as the rookie went on to compile a 2.28 ERA in 27.2 innings over 26 appearances, ringing up hitters and Wrigleyville cash registers all the while.

It wasn’t until 2012 that Samardzija finally became a starter with the Cubs. And while his first two seasons in the rotation were anything but consistent, they provided frequent glimpses of great potential. That persistent sense of if only was the white rabbit Samardzija and the Cubs would hunt with divergent conviction — the pitcher believing it all was a matter of when, while the organization was reluctant to chase the hare any further than it could.

Things came to a head in 2014. The Cubs were abysmal, and Samardzija’s record — a ghastly 2–7 despite a sterling 2.83 ERA — reflected as much. The gambler knew it was time to make his move. By then, Shark had grown comfortable enough with his breaking ball to consistently mix it with his heater, a development that motivated Chicago to offer him a 5-year, $60 million contract.

Samardzija laughed. And while Theo Epstein & Co. were allegedly reluctant to spend big so early in the new regime, they reportedly upped the offer to $80 or even $85 million over the same 5-year span.

There was just one small problem: A guy named Homer Bailey had recently signed with division-rival Cincinnati for six years and $105 million — and Samardzija knew he was better. So he shunned the deal, and the Cubs were left with no choice but to trade their best pitcher.

The trade of Jeff Samardzija and Jason Hammel to the A’s for Addison Russell, Billy McKinney and Dan Straily would prove to be a turning point for the Cubs and their former would-be ace. In rebuffing Chicago’s overtures, Samardzija had chosen to bet on himself — and big. He’d gone all-in on eventually commanding more than the $80 million he’d been offered.

It was a ballsy move, to be sure, but it was by no means the first of its kind.

A prime example comes from the NFL and Joe Flacco, who in 2008 signed a rookie contract worth about $30 million over five years. After injury and illness took out the top two QBs on the Baltimore Ravens’ depth chart, an extremely self-aware Flacco grabbed the starting role and ran with it.

Prior to the start of the 2012 season, Flacco — now entering the final season of that rookie deal — was angling for a new pact. Coming off a 12–4 record and a near Super Bowl berth, Flacco knew what he wanted and wasn’t shy in expressing why he thought he deserved it.

“I mean, I think I’m the best,” the Raven crowed. “I don’t think I’m top five, I think I’m the best. I don’t think I’d be very successful at my job if I didn’t feel that way. I mean, c’mon? That’s not really too tough of a question.”

Still, Baltimore was unwilling to pay him commensurate with the upper echelon of his fellow QBs, so contract talks were tabled as Flacco chose to let his performance dictate a higher salary than the $16 million per season he reportedly turned down.

Everyone knows how that turned out. Flacco carried his team to a Super Bowl title on the strength of a playoff run that featured an NFL-best 11 touchdown passes against zero interceptions.

Even Rod Tidwell was like, “Dayummmmm!”

Just one month after hoisting the Lombardi trophy, Flacco signed a six-year, $120.6 million contract that made him the highest-paid QB in NFL history.

In baseball, there was Max Scherzer, who in 2013 elected to play for the Detroit Tigers and the $15.52M awarded him during his final year of arbitration, rather than accept the club’s reported six-year, $144 million pact — a deal that would’ve placed him among the six highest-paid players in the game.

The reigning Cy Young winner felt he’d be able to parlay another strong season into an even bigger deal in free agency.

The gambit worked, to the tune of a seven-year, $210 million deal with the Washington Nationals that included a $50 million signing bonus. Scherzer will earn $105 million in the final three years of the deal alone, and it supposedly grants him managerial override powers (!), as well.

In the NBA, it was Lance Stephenson, who famously blew in LeBron’s ear before turning down five years and $44 million from the Indiana Pacers. The following summer, he wound up taking a three-year, $27 million deal with the Charlotte Hornets instead. The reason: Stephenson was coming off a breakout season with the Pacers, and was understandably looking to leverage an even bigger deal down the road. While the longer deal guaranteed more money, it would’ve taken Stephenson to age 29 and likely reduced the value of his next contract. Instead, he went shorter to go bigger in three years.

If you come at the King, you best blow a kiss.

Stephenson, of course, never fit in with the Hornets, and was traded to the Los Angeles Clippers after the 2014–15 season. He still has two years to rehabilitate his image and take advantage of his strategy, but his ability to recoup the money he passed up is, by now, in serious doubt.

Back to baseball, there is Ian Desmond, the Washington Nationals shortstop who reportedly turned down a seven-year, $107 million offer prior to the 2014 season. After batting .292 with 25 home runs and 21 steals in 2012, and then going .280 with 20 bombs and another 21 steals in 2013, Desmond chose to pass up the huge payday in favor of a two-year, $17.5M deal. He preferred to reach free agency that much sooner, where he likely saw the eight-year, $120 million Elvis Andrus had gotten as a baseline for his future pact.

Desmond smacked 24 home runs and drove in a career-high 91 runs in 2014; he even had 24 steals. But his batting average dipped to .255, while his strikeout rate climbed from 22 to 28 percent. In 2015, that average dropped to .233, with a walk rate hovering around five percent.

Desmond will still command a decent salary, but the market’s not going to be quite as strong for a 30-year-old, offense-first SS with obvious holes in his swing.

Come to think of it, maybe Samardzija should’ve taken the $80 million.

In June 2014, the A’s traded for Shark as part of an all-in gamble of their own. The organization best known as an incubation chamber for other teams’ talent wound up doing the impossible: trading for three-fifths of its starting rotation midseason, and instantly solidifying its status as World Series favorites. But the A's faded down the stretch, eventually falling to the Royals in a heartbreaking Wild Card round matchup, and found that the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow was really just iron pyrite.

Billy Beane was left with no choice but to break up the band.

Lester and Hammel signed in Chicago to anchor a Cubs rotation that had been depleted by the departure of Samardzija only a few months before. Still seeking the leverage he needed to score that big deal, Samardzija, too, found himself back in Chicago, but on the other side of town. In what many viewed at the time as a huge coup, the White Sox sent infielder Marcus Semien, right-hander Chris Bassitt, catcher Josh Phegley, and first baseman Rangel Ravelo to Oakland in exchange for the big pitcher.

If you’re keeping score at home, that was seven prospects involved in two big trades that took place in a five-month span — all centered around one man in search of that big score.

If ever there was a situation tailor-made to help Samardzija sew up that big deal, this was it — principally because he wouldn’t have to be the team’s ace, a role already held by Chris Sale. Until it wasn’t.

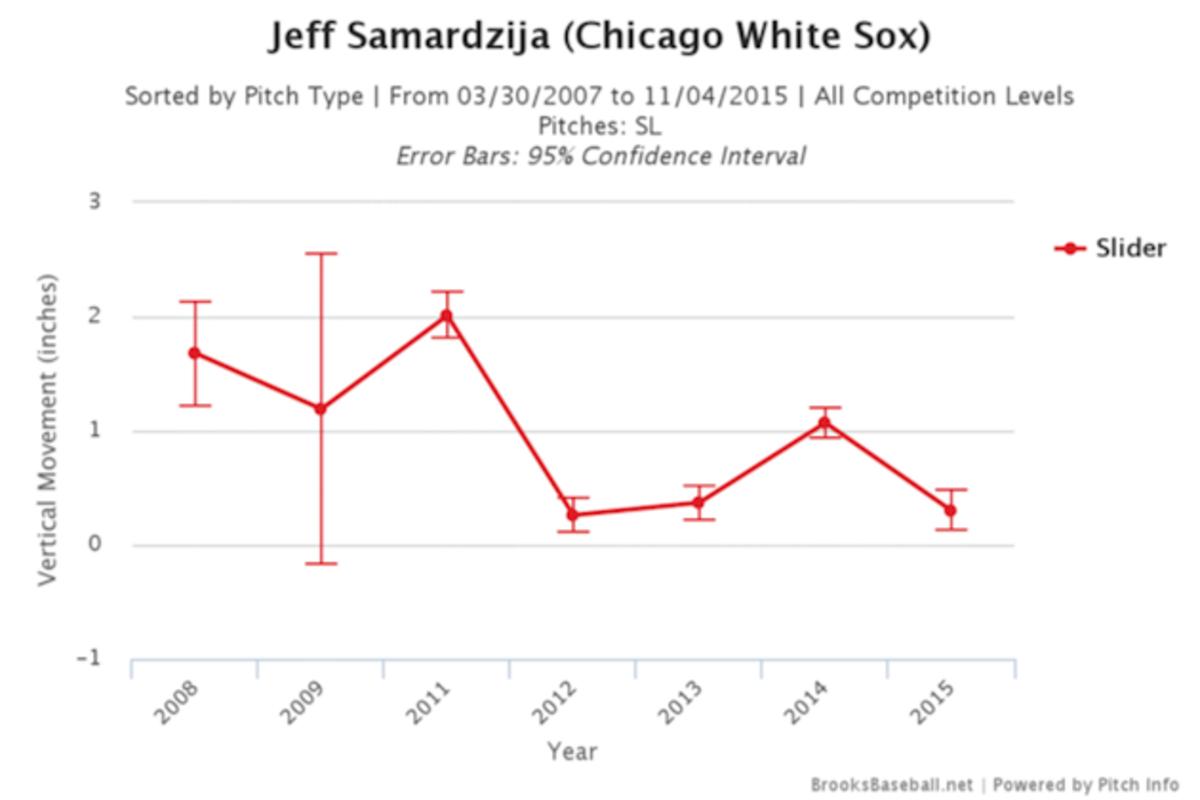

Remember that slider he had grown so comfortable with? AL hitters quickly grew comfortable with it as well, batting .312 with a .518 slugging percentage against the breaking pitch. Just a year prior, those marks were .211 and .333. According to FanGraphs, Samardzija’s slider was the 9th-most effective in the Majors in 2014; in 2015, it ranked 51st among 52 pitchers for whom sufficient data exists.

So what happened? It’s impossible to say definitively, but control and location are certainly culprits. Namely, Samardzija isn’t getting as much vertical movement on the slider and he was leaving it in the zone far too often.

Baseball is a game of fractions of time and distance, but when you’re getting only 0.3 inches of drop, you’re not going to fool too many hitters, even if your slider’s horizontal movement has remained pretty much the same as when it was effective. But it’s more than just that one pitch. Matt Spiegel of 670 The Score in Chicago wrote about how Samardzija’s entire repertoire has changed drastically.

Samardzija has primarily used a sinking fastball, four-seam fastball, slider, splitter, and a cutter. He toyed with a curve and a changeup early in his career, but both are long gone.

He started to use the cut fastball in 2010. According to Fangraphs.com, here are the percentages of cutters among all his pitches thrown, year-by-year: 7.7, 7.0, 9.1, 10.8, 12.3, and 23.5

Yes, in 2015 he has thrown more than double the percentage of that pitch than the rest of career. His overall fastball percentage in 2015 is a career low 39.9 percent. He has never been below 53 percent in any season.

Samardzija is one of only six qualifying starters who have thrown less than 40 percent fastballs, and one of those is knuckleballer R.A. Dickey.

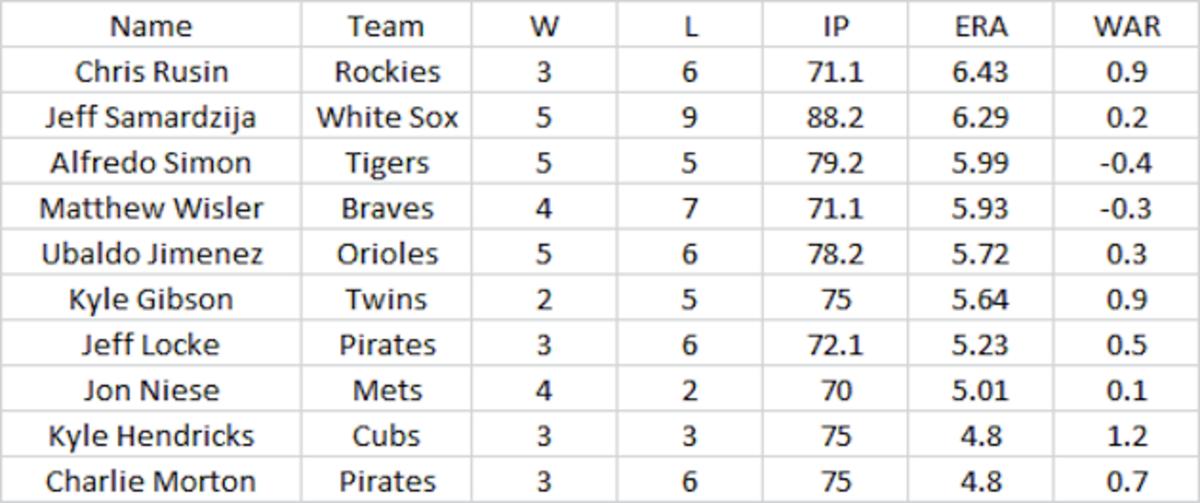

Regardless of the cause(s) of Samardzija's decline, we’re left with a pitcher on the wrong side of 30 — he’ll turn 31 in January — who just finished the worst season of his career during a contract year, and who’s already been traded twice.

He has gone from a potential $100 million man to a guy the Sox had to think long and hard about making a qualifying offer to. Major League Baseball has a system in place to protect teams from having their talent signed away by teams with deeper pockets. If you make a qualifying offer — an amount equal to the average of the top 125 salaries in baseball, roughly $15.8 million — to a pending free agent and he signs elsewhere, your team receives a compensatory first-round pick.

Since no player has ever accepted a QO, it’s basically a way for teams to score a free pick in exchange for making a hollow offer to a guy they know is going to want a bigger long-term deal. But desperation is a stinky cologne. Samardzija turned down $16 milliion to $17 million a season for five seasons (a figure some feel he can still approach in free agency) because he felt he had his hand on the tiller, but for a while there, it looked as though he’d be willing to stick his hand in the till for a little less than that over just a single season.

Really, it was the White Sox who were in a precarious situation as the season drew to a close. After a disappointing campaign on the South Side, they need to re-evaluate their strategy moving forward. The trade for Samardzija seemed perfect at the time because it gave them what they thought was an arm that would help them contend in the AL Central. If he performed well, they’d reap the benefits and would at least get a draft pick when he signed a mega-deal elsewhere. If he was simply mediocre, maybe they’d be able to afford to keep him in Chicago long-term. But after he completely fell apart, they had to consider letting him walk and getting nothing in return.

After all, by giving Samardzija a qualifying offer, the Sox ran the risk that he’d actually take it, and it's not a good look to be paying top-of-the-rotation money to a guy who was one the worst pitchers in baseball — 6.29 ERA, 0.2 WAR — over the second half of the season, especially when that QO represents more than a 50 percent raise over his current salary.

On the other hand, this is the same guy who, in his first start following that 10-run shambles of a game, absolutely dominated the Detroit Tigers. Samardzija needed only 88 pitches as he faced only one more than the minimum in completing a one-hit shutout of his division rivals, striking out six and walking none.

Jeff Samardzija joins this odd list: 9+ inning complete games with higher game score than number of pitches thrown

— Christopher Kamka (@ckamka) September 21, 2015

http://t.co/oQsqF9GmWt

Then he allowed just two solo homers in seven innings against the eventual world champion Royals. Two starts can't erase the 10 bad ones before it, but they showed Samardzija still has the juice required to get a lot of outs.

Samardzija thought he was holding the winning hand when he stared down Cubs’ management last year. He may still believe that, but he may be left without enough chips to make a real bet. He’ll need to find a team willing to fork over a big payday and a draft pick, all while gambling on the return of the slider and that he still has something left to match the blazing fastball that got him here in the first place.

No matter where he ends up, Shark is going to earn a fair wage to throw a baseball over the next few years. He’s just going to have to take a haircut to do so.