A Brush With Greatness: The Puma Shoe That Upended the 1968 Olympics

For much of 1968, Tommie Smith and John Carlos were just two college sprinters; Echo Summit was just an anonymous patch of California forest; and the so-called “brush shoe” was just an unproven idea in some German cobbler’s imagination. That all changed on Sept. 12.

In the preceding weeks, U.S. Olympic officials had descended upon a remote, wooded peak near Lake Tahoe and carved a massive crop circle into the untouched timberland, laying down a rubberized, all-weather track amid the 200-foot pines. Echo Summit’s elevation, 7,382 feet, was almost identical to that of Mexico City, host of the upcoming Summer Games, and so here the USOC would hold its trials.

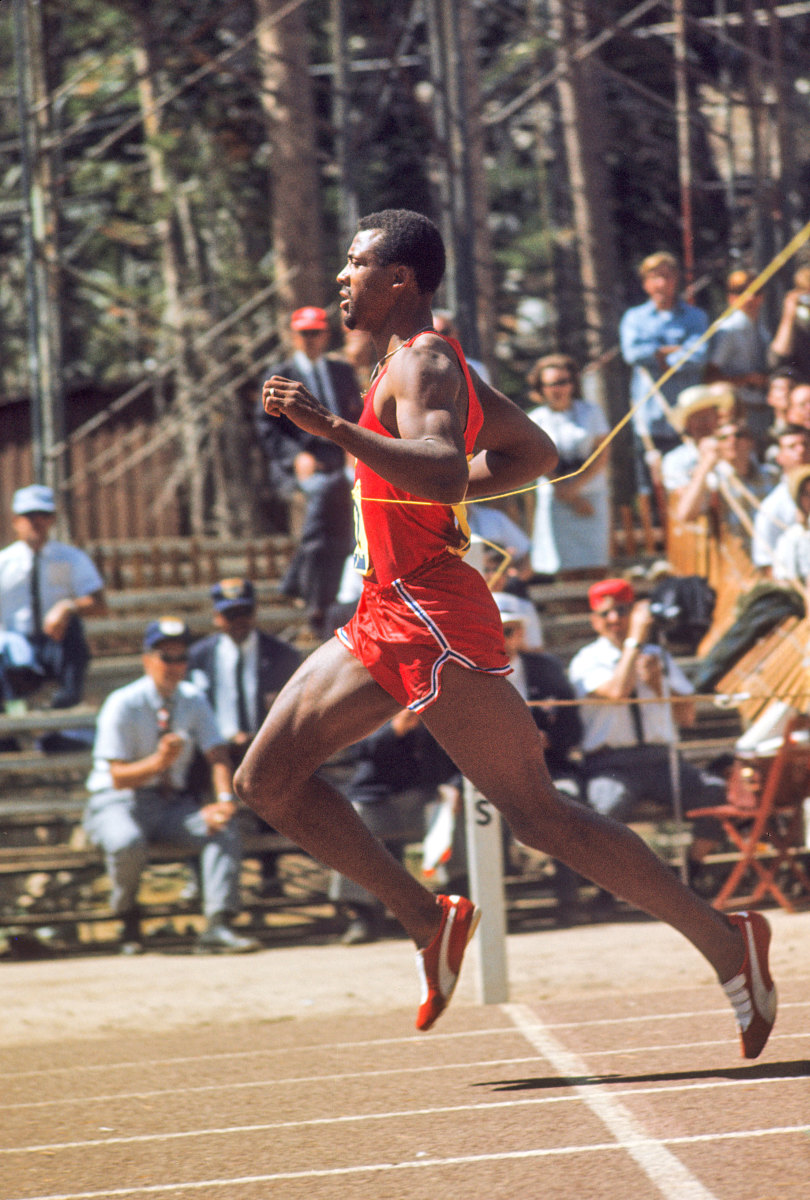

Strutting toward the starting line before the 200-meter final that September afternoon in a pair of sleek, red Pumas was the 23-year-old Carlos, whom this magazine would introduce later that month as “a goateed, jive-talking slum kid from Harlem who remembers his neighborhood as a place where kids drank cheap Scotch and who believes that at least part of his mission in life is to point up the implications of that fact to the Establishment.” Situated in lane 4, Carlos wore shoes that appeared identical to the ones that Smith, 24, was wearing in lane 1. Same cherry-red suede, same tapered white Puma stripe on their flanks, same new closure system—a space-age replacement for shoestrings called Velcro. But instead of the traditional four spikes on Smith’s soles, Carlos’s shoes that day featured 68 spikelettes—tiny, steel piranha teeth aligned like brush bristles under the balls of his feet. Puma had chosen 68 as a nod to that summer’s Games, where one month later the brush shoe would make its Olympic debut along with the rust-colored, spongy track surface, called Tartan, with which the shoe had been designed to interact.

Smith, in the dreaded inside lane, left shoulder almost touching the towering evergreens still standing in the infield, had tried the brush shoe in the preceding days and had “liked it because of the stability,” he recalls. But he refrained from racing in it, afraid of the unknown. “That shoe scared me,” he says.

To demonstrate the advantage afforded by the brush shoe, Steve Williams, the World’s Fastest Man in the early 1970s, asks that you consider combing an Afro with a four-bristle brush versus one that has 68. The former will move through the hair stubbornly. The latter won’t budge at all. “In that brush shoe,” he says, “when you put your foot down in the curve, it grabs that rubber track and doesn’t shift from left to right.”

Like a limited-edition Porsche, only 500 pairs were manufactured. Of those, about 100 had been shipped from Puma headquarters in Germany to the site that would give the shoe its retail name, the Tahoe, even though it would never appear on a store shelf or otherwise be offered for sale.

The trees at Echo Summit obscured the beginning of the race from spectators, who were situated near the finish line. Seconds after the starting gun, Carlos burst out of the woods, zooming around the turn, the race, for all intents and purposes, already over. He eased through the tape with a stunning two-stride lead, having defeated Smith for the first time in their careers, clocking the first sub-20-second 200 in history: 19.7.

Years later, Smith would write in his book, Silent Gesture: “Carlos couldn’t have been beaten that day, not by me or anyone. . . . It would have been his world record, but we told him not to wear those shoes.”

***

Perhaps Carlos’s epic run might not have drawn scrutiny if U.S. teammate Vince Matthews hadn’t worn the brush shoe while breaking the 400-meter world record two weeks earlier. Or if Matthews’s new mark hadn’t been bested by Lee Evans, also in the brush shoe, in the 400 final. (Matthews switched back to traditional spikes before that final and finished fourth; and the day before Carlos ran his 19.7, he ran nearly a half-second slower wearing a standard four-spike Puma.) But long-standing -records were falling like the trees that had once covered Echo Summit, and the evidence suggested Puma’s crimson velour hot rods had something to do with it. The shoe’s mystique was cemented when a photo captured Carlos, after winning the 200 final, holding up a brush shoe like King Arthur wielding Excalibur.

“It took the world by storm,” says Art Simburg, formerly Puma’s top athlete liaison in the U.S., who as a bushy-haired 24-year-old had delivered the brush shoes to Echo Summit. “And then it was gone.”

The story of the brush shoe began not at that man-made oval in the forest, but 70-odd years earlier, halfway around the world, when two brothers were born in a small German town with a big name: Herzogenaurach.

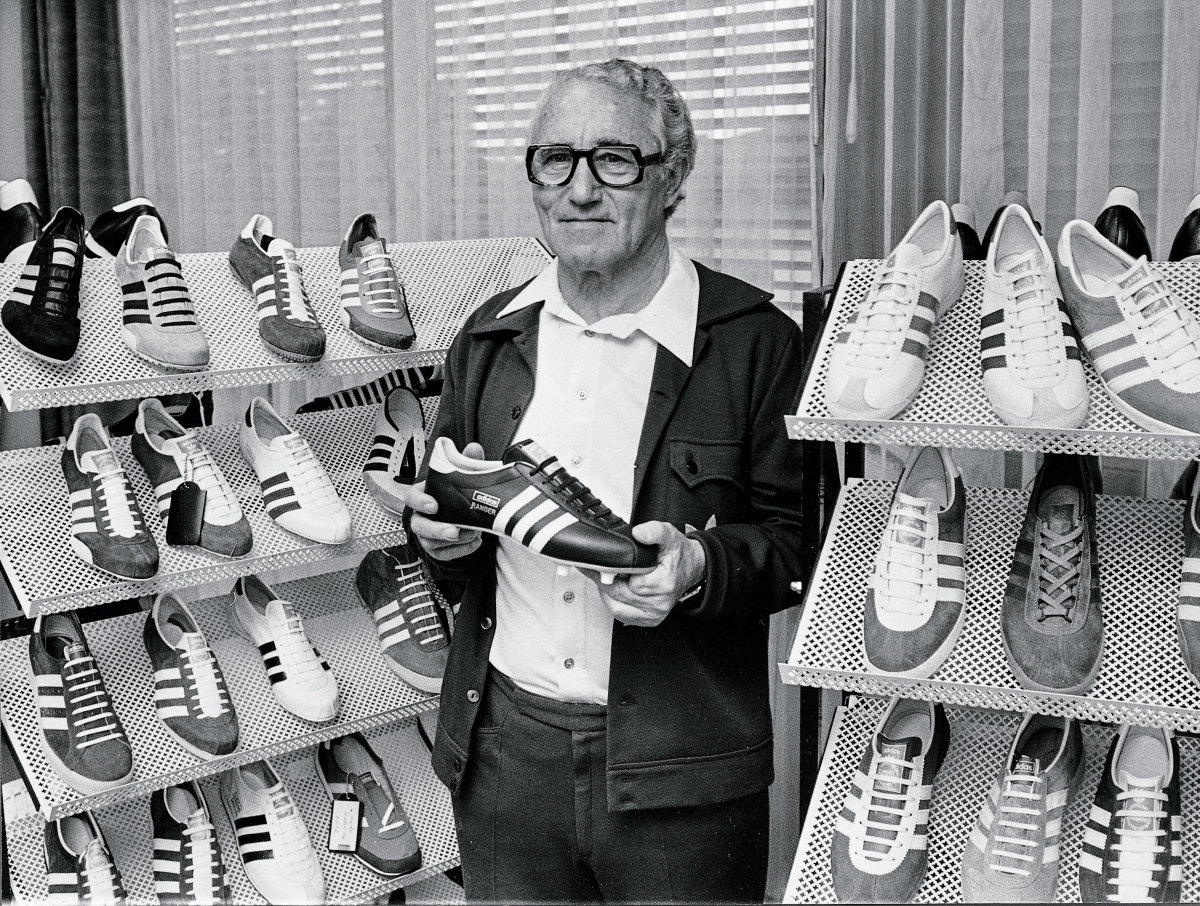

The older of the two Dassler boys was Rudolf (or Rudi), who would become a brash businessman, as loud as his younger brother, Adolf (Adi), was quiet. Adi would become a master shoemaker—an artist, really—obsessed with sport and the idea that footwear could enhance performance. In his early 20s he invented one of the first spiked shoes, its metal thorns forged by the blacksmith father of a friend.

The Dassler brothers signed up with the Nazi party in 1933, three months after Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor. At the ’36 Olympics, Adi summoned the courage to hand a pair of his track spikes to an American sprinter named Jesse Owens, who ended up performing quite well in them. Dassler Brothers Shoe Factory was off and running, with Rudi in the role of salesman.

Seven months before those ’36 Games, Adi and his wife, Kathe, had a son named Horst, who would one day lead the company through an epoch of stunning growth and international influence, and who would play a prominent role in the brush shoe’s brief biography. But first there was war.

Rudi served, holding an office job on the eastern front. Adi did not, having been advised to stay home and make barrels for anti-tank guns for the Nazis. After World War II, the Allies prosecuted Rudi for his allegiance to the Reich, imprisoning him for a year. Adi was fined and then absolved. Rudi accused his brother of ratting him out as a Hitler loyalist so that Adi could assume greater control of their growing footwear business.

The brothers’ relationship didn’t dissolve as much as it was burned clear through by acid. Adi and Rudi and their families still lived together in the same villa, but their wives loathed each other, and their children were scarcely allowed to stand near their first cousins. In 1948, Rudi left the company to set up a competing shoeworks on the other side of the Aurach River. That outfit would eventually be called Puma. Adi, meanwhile, rebranded his business as Adidas, for Adi DAS-sler.

During the two decades between that split and the advent of the brush shoe, Adolf and Rudolf exchanged not “a single word except on legal matters,” SI’s John Underwood wrote in 1969. “They sue each other regularly. . . . The estrangement of the brothers’ houses is absolute, the acrimony unremitting. As a result, their shoemaking is unsurpassed.”

By the late ’60s, their sons had taken the helm of the two businesses. Armin deferred to his overbearing father, Rudolf, on all matters Puma, while Horst, empowered by his dad’s confidence in him, made Adidas his own.

The greatest ingredient in Horst Dassler’s overwhelming success was his hospitality, his bonhomie. Williams called him “the consummate host; he knew everyone.” He also kept notes on everyone—every athlete, every promoter, every IOC and track executive. He knew their kids’ names, their wives’ birthdays. . . . He knew other details about them too.

“Don’t cross him,” laughs David Jones, a 1960 Olympic sprint medalist for Great Britain and an ex-sneaker trafficker who at 79 introduces himself as “one of the few men ever to work for both sets of Dasslers and live to tell the tale.”

Across the litany of books that have told Horst Dassler’s tale, a portrait emerges of a man deferential and warm, as comfortable with an inner-city sprinter like John Carlos as he was with a ruling-class Spaniard like future IOC president Juan Antonio Samaranch. A sage impossible not to converse and laugh with. A man every bit as competitive and insecure as the planet’s top sprinters. “Officially, [Horst] was just a sports manufacturer,” University of Chicago sports sociologist John MacAloon said upon Horst’s death, of cancer, in 1987, “but behind the scenes he was the most powerful man in international sport, and probably the single most influential person since [former IOC president] Avery Brundage.”

“Horst became the puppet-master of the sporting world, pulling the strings to create massive changes,” his trusted business partner, Patrick Nally, said in the 1992 book The Lords of the Rings. “Horst got a tremendous buzz from controlling and manipulating.”

By 1968, he had built the most powerful shoe brand in the world. “Adidas was number one, there was no number two, and Puma was number three,” says 89-year-old Dick Bank, a former Adidas distributor and TV analyst. Nike’s ascent was still a decade off. Most of the world’s top athletes were on Horst’s payroll, whether under the table (as with “amateur” Olympians) or over it (as with pro tennis star Stan Smith). When the new rubberized Tartan track was unveiled in the summer of ’68, the sprinting world assumed that Adidas, ever the innovators, already had the perfect shoe for it.

But Puma had timed the starting gun just right. The brush shoe was Rudi’s chance to leap into the future. If Puma could master the connection between the human foot and these new synthetic tracks, and slip that technology onto the feet of the fastest men in the world, Rudi might finally break his brother’s monopoly.

Puma kept its design secret for months, Simburg recalls, “so it would be as much of a surprise, and have as explosive an impact as possible.” The only apparent obstacle was the rule book of the International Association of Athletics -Federation—written decades earlier, for dirt tracks—which decreed that shoes could have no more than eight spikes. “What Puma hoped to achieve,” says Simburg, “was for each row of spikelettes—there were six rows—to be considered a single spike.”

Jones suspects that a well-known shoe designer helped Puma draw up what the company called the bürstenschuhe. The boss, though, disputed that. The new kicks were “my idea,” Rudi told SI in 1969, between puffs on his ever-present cigar.

To which Bank, as salty as he was 50 years ago, retorts: “Rudolf Dassler never invented anything!”

***

Shortly After athletes arrived at Echo Summit in 1968, Simburg, Puma’s man on the scene, showed up at their barracks “all excited, saying that Puma had made a new shoe and they wanted me and Tommie [Smith] to test it,” recalls Lee Evans, now 72.

The visual aesthetic struck Evans first. “It was a good looking shoe, I liked it right away.” And on the track? “Fantastic. The shoe was lighter in weight. There was definitely a better grip to the surface of the track. There were none of the pointy feelings under your feet that you would get with regular spikes. I knew right away I was going to run faster.”

The most widely televised Olympic Games in history were days away. The fastest men in the world were setting records in a shoe designed by Adidas’s sworn enemy. Other sprinters were training in it, talking about it. The American track and field team, still widely considered the greatest ever, was packing its bags for Mexico. Puma stood poised to capitalize when the gold medals started pouring in.

They felt confident the IAAF wouldn’t stand in the shoe’s way. “And for a moment,” Simburg recalls, “it did seem that way.”

Then, on Sept. 28, two weeks before the opening ceremonies, IAAF Secretary Treasurer Donald Pain announced that he’d sent notice around the Olympic Village: “No technical rule can be changed during an Olympic year, and the rule on track shoes now requires a maximum of eight spikes.”

Puma had a compelling argument that 68 pins, each just four millimeters in length—roughly the length of a popcorn kernel—shouldn’t be equated with the half-dozen carpenter’s nails that jutted from other shoes’ soles. But that got Puma nowhere. “The rule regarding this is as it stands,” Pain declared, “and it is a definite thing.” The slew of records that had been set in the brush shoe were erased from the books.

Rumors swirled, and still persist, that Horst Dassler played a major role in the brush shoe’s extinction. Evans, for one, told Track in the Forest author Bob Burns that Horst “had the shoes banned because he knew if he didn’t, everyone would have worn them.”

Carlos told his biographers the shoe went away because “Adidas was waving a whole lot of money in front of the IAAF.”

Asked recently whether Adidas applied undue pressure on the IAAF pertaining to the brush shoe matter, John Boulter, a two-time Olympian and long-term executive at Adidas, says plainly, “Of course. It’s self-evident.”

Puma’s own employee magazine, Puma CATchup, asserted in 2014 that the world records set in Echo Summit had simply been “too much for Adidas. They heavily intervened. . . . [An unnamed Adidas operative] is said to have paid a total of 75,000 DM to IAAF officials.”

But this is the least plausible explanation for the brush shoe’s disappearance. The U.S. equivalent of $19,000 in 1968 Deutsche Marks wouldn’t have raised even one of Lord Burghley’s eyebrows. The IAAF president at the time, Burghley, also known as the Marquess of Exeter, led a council of similarly moneyed men, mostly British, who could have dug 19 grand out of the backseats of their Rolls-Royces.

No, convincing the IAAF to rule in Adidas’s favor, at the 11th hour, on a matter that stood to create a less momentous Olympics—if such convincing had indeed been attempted—would have required something other than a sack of cash.

***

Which brings us to Horst Dassler’s chalet in the French countryside. That’s where Steve Williams says he found himself one evening in July 1975, his slim, 6' 4" frame nestled into a leather sofa in the big man’s office. Williams, the intermittent world record-holder in the 100 and 200 throughout the ’70s, recalls several such meetings at Horst’s estate outside Strasbourg, “sitting in the basement, drinking 300-year-old Napoleon cognac worth $1,000 a bottle.” On that particular day, Williams says, Dassler offered the American a Havana cigar. When Williams demurred, “Horst said, ‘I’ll fix it for you.’ He carved it out and stuck hashish in the tip.” Williams laughs at the memory. “I was 21 years old!”

It should be noted that by this point the middle-aged German tycoon and the fleet-footed kid from the Bronx were thick as thieves, according to Williams. He says Horst had provided him personal checks, including a monthly stipend in college; a Porsche with a pricey Blaupunkt stereo; international travel for him and his significant others; and, at least once, a Parisian prostitute. They’d even begun designing a shoe together—that’s what they were discussing in Horst’s lair when “he asked me what my favorite shoe was of all time.”

The sprinter didn’t hesitate. “The brush shoe, of course.”

“He gives me this sly smile,” Williams says, pausing for effect. “After a few more drinks he proceeds to tell me, clear as a bell, ‘We blackmailed three IAAF officials to make their ruling. One guy was gay, another was involved in some sort of financial malfeasance—at the time I had never heard the word malfeasance!—and another guy was cheating on his wife.’ ”

These three gentlemen did not want their personal matters made public, according to Williams’s retelling, and thus were motivated to do Horst’s bidding. “He told me, ‘There were six guys on [the IAAF board]. Two were on our side and we blackmailed three, so we won the ruling. Boom—just like that.’ ”

No one but Williams seems to have heard this story.

“I was very close to Horst,” recalls Dick Bank. “He didn’t tell me everything, but I’ve never heard a bit of that.” Bank does, however, recall the blast of records at Echo Summit and the pair of brush shoes he had shipped from that site to his home in L.A. “I got the shoes,” he says, “sent them to Horst Dassler, and we got them banned faster than you could say Puma.”

Adidas, today, hasn’t offered a response to any of this—it’s 50 years on, after all. Nor has the Dassler family, which sold Adidas in 1990. But Williams’s blackmail story did create a regrettable scene, set in modern times, in which a middle-aged American journalist sat inspecting a black-and-white photo of the entire IAAF council from that era—11 well-heeled, pale men, each in suit and tie, each since deceased—wondering which of them was gay, which was the philanderer and which was the white-collar crook.

Said journalist sifted through old news stories about the IAAF brass and scoured microfiched obituaries in search of telling details. A supportive IAAF spokesperson, meanwhile, said the outfit’s records from that time are “not particularly detailed” and contain “no reference as to who exactly decided the brush spikes did not comply with the technical rules.”

David Jones, the loquacious British track scenester, compares this blackmail mystery to the old board game Clue—“which was ruined in America, by the way.” (One could say the same about the brush shoe.) Jones and his old track friends, world-class British athletes from the ’50s and ’60s, rubbed elbows with upper-crust IAAF-council types for decades. They are sure they know who the three allegedly compromised members are. Or were. But being gentlemen, they’d rather not say.

For all its protestations over the legality of the brush shoe, Adidas had no qualms about embracing the technology. “Adidas wanted it banned because they considered it illegal,” says Ralph Serna, an elite distance runner turned sport-shoe historian and designer, “but they were also working on a version of it.”

In an issue of Track and Field News that was published nine days before the Mexico City Games, notice came that Adidas had developed an “experimental” sprint shoe, “the Quill,” featuring 42 minispikes at the forefoot, a bit of news that surely elicited some choice German epithets from inside Puma headquarters. Neither Adidas’s nor Puma’s brush shoe touched the track at the Games, of course, or any other IAAF competition afterward. Not legally, anyway.

As for the ’68 Olympics, Lee Evans’s vacated 400-meter record from Echo Summit would have been broken by the 43.86 he ran in Mexico City, wearing traditional spikes. It was a new world record, and yet, “I believe I would have ran faster in the brush shoe,” Evans recalls. “Everyone on the Olympic team wanted to run in that shoe.”

Neither Carlos nor Smith was wearing it for their highly anticipated rematch in the 200-meter final. Over the first 120 meters, Carlos ran 12.2, a blistering pace that he couldn’t sustain. Smith bolted past Carlos—both in traditional four-spike Pumas—as they came out of the turn and sped down the homestretch, gliding to the top of the medal stand, where the two men made a different kind of history.

We remember their raised, black-gloved fists and lowered heads, but few people noticed the single black Puma sneaker lying at each man’s socked feet as the national anthem played. At the time, Smith told SI that he and Carlos simply “didn’t want to leave the shoes lying around for somebody to steal.” Fifty-one years later, he’s more forthright: “Puma was like family. The camaraderie between me and Puma was about more than shoes.” They had helped feed his wife and child at a time when Olympians earned zip. Simburg, his Puma contact, not only helped in that effort, he flew back to the Bay Area with Smith and Carlos after their podium protest and rode out the death threats with them.

***

There is something melancholic about the full-page advertisement, reserved before Mexico City but published just after it, that appeared in Track and Field News that October. The ad announced the arrival of “The World Beaters, Puma’s WONDER Shoes.” They still didn’t have a name; instead, Puma called them “no. 296 . . . the track shoe of tomorrow that Puma is making today.”

But, for the most part, their day had already come and gone.

Steve Williams wore them off-and-on in the early ’70s at San Diego State, where college officials were more lenient in patrolling soles. He trained in them, too, after his international career took off later in that decade—and every time he pulled those Velcro straps over his metatarsals he thought of the secret Horst Dassler had shared in his French manse. In specific, Williams reflected upon a race he’d run a month before he says he heard Horst’s blackmail tale, when he and Don Quarrie broke the 200 record Smith set in Mexico City—“a record that shouldn’t have been there,” Williams says, “because of Horst Dassler’s games.”

By the late ’70s, plastic spikes had replaced metal ones as the industry standard, nullifying the IAAF’s rule on steel spikes. “That was the first, legal way to get around it,” says Serna. Still, the brush shoe’s brief, thrilling life—a 60-meter dash of rumors and records—left a mark much deeper than the holes it poked into Echo Summit’s synthetic track. Celebrated Nike designer Nelson Farris, a recognized authority on such matters, says the brush shoe “opened the door to creative thinking about the future in track spikes.” He frames the Tahoe as a bridge between Jesse Owens’s gear and the ceramic composite spikes of today, which cover modern soles like stalactites on a cave ceiling.

Ultimately, Serna believes that the brush shoe’s hasty banishment prevented it from being studied and improved upon. “Think of how [shoe companies] could have evolved their best product over the last 50 years,” he says. “Today’s [track spike] would be something we would never have dreamt of.”

What ever happened to the O.G. brush shoes that remained from the original 500 pairs? Tommie Smith gave his to a museum in Texas. A large majority, though, says a Puma spokesman, were “destroyed after the ban. We still have a few pairs in our archives.”

Ralph Serna remembers finding a set in the mid-’70s, when he was a high school distance phenom, amid a pile of remainders in Simburg’s Hollywood garage. He likened it to discovering a Babe Ruth baseball card. Thirty years later, nearing middle-age but still a shoe-obsessed kid at heart, he was rummaging through a bin in the back of a second-hand shop in Boston when he discovered another pair of the red, prickly-soled fossils. He says: “I asked the guy—trying to keep cool and not look interested—‘How much are these?’”

“Five bucks.”

For all its lore and intrigue—Nazis, fraternal hatred, -hashish—the only thing the brush legend ever lacked was hard proof that the shoe provided runners an advantage. Then the existence of an obscure 1972 research study, conducted at Ohio University, revealed itself this year, not unlike Serna’s thrift-store find.

The only copy, bound in a hard, brown cover and titled “An Experimental Test of the Puma Model Number 296 Brush Spike Shoe,” contains a record of hundreds of 45‑meter sprints run by six test subjects—members of the local college and high school track teams—in 1970. Each subject ran in both the brush shoe and a traditional pair of spikes, after which the study’s author, Donald W. Wood, determined that five of the six subjects ran faster in the banned shoe. Wood wrote that he regretted conducting the tests at such a short distance, and without a turn. Still, “these results tend to favor the brush spike shoe regarding improvement of sprint-running performance.”

John Carlos was more succinct in the moments that followed his blazing 200 at Echo Summit, as the first skepticism about his strange new footwear crept in. Regarding the

unofficial record he’d just set, in a time that wouldn’t be bested for 28 years, he told inquisitive reporters: “You saw it, and you’ll write it.”