You Relays Got a Hold On Me

Some five decades after Dave Johnson’s first Penn Relays, the details still return to him with ease. There was the tingling sensation he felt on that mild Saturday morning in late April 1968, arriving at Franklin Field as an alternate miler for his high school team and seeing an “absolutely mind-boggling” crowd of nearly 29,000 track fans—more spectators than he’d ever seen, save for that time his dad took him to Connie Mack Stadium to watch Sandy Koufax pitch. And the chills he got leaving the Relays that night, hustling to the parking lot with a coach who was hell-bent on beating traffic, when Villanova’s Larry James set a meet record with a scorching 43.9-second anchor leg in the 4x440 final and the stadium’s roar rumbled through the streets of West Philadelphia.

“That’s what I remember,” says Johnson, whose wide-eyed fascination would later turn into a full-time job, director of the Penn Relays, that he has held since 1996. “Just the enormity of it all.”

Haven’t been? Haven’t heard? Originally staged in 1895 as a single-day track and field meet for East Coast high school and college students, who squared off in events such as a two-mile bicycle race, a one-mile walk and “putting the shot,” the Penn Relays have since evolved into an international sporting spectacle. “If you run track and field, that’s something you want to participate in,” says Ron Bazil, who attended 34 straight Relays from 1968 through 2002 as the coach at Adelphia, Army and Tulane. “If you can’t, you at least want to be a spectator, to see the glamour. That’s the Mecca, really.”

The list of celebrity alumni is eye-popping enough. To name a few: Jim Thorpe, Jesse Owens, Roger Bannister, Wilma Rudolph, Allyson Felix, Usain Bolt and an Army pole vaulter named Edwin Aldrin, who would later attain greater fame for soaring much higher than the 12' 6" he cleared (tied for fifth place) in 1950. But consider the full scope.

Through last spring, the Relays had added up approximately 800,000 total registrants over the years, spanning ages eight to 100 (in the masters division), representing three dozen countries in 2019 (including eight government bodies who sent envoys of their nations' best). Now held over three full days, always hooked to the last Saturday in April, the action runs from dawn to dark, per a frenzied yet precise schedule. “Races start every five minutes, but if we need to we can do it in four,” says Johnson. “From the time the last runner finishes until the next gun goes off, we average between 10 to 15 seconds.”

That pace allows little respite for the fans who ring Franklin Field’s brick parapet each spring—close to 2.2 million total since 2000, more than any track meet short of the world championships or Summer Olympics. “There’s constant shrieking, bursts of cheering … ” Johnson says. “It’s a madhouse.”

Gold watches are traditionally awarded to most champions, but glory is equally prized. “I used to be ashamed that the Penn Relays were so important to me,” legendary Villanova coach Marty Stern confessed to Penn’s student paper, The Daily Pennsylvanian, in 1991. “During the Vietnam War, I would think to myself: How can I care so much about my team winning at the Penn Relays when people are being unnecessarily killed?’”

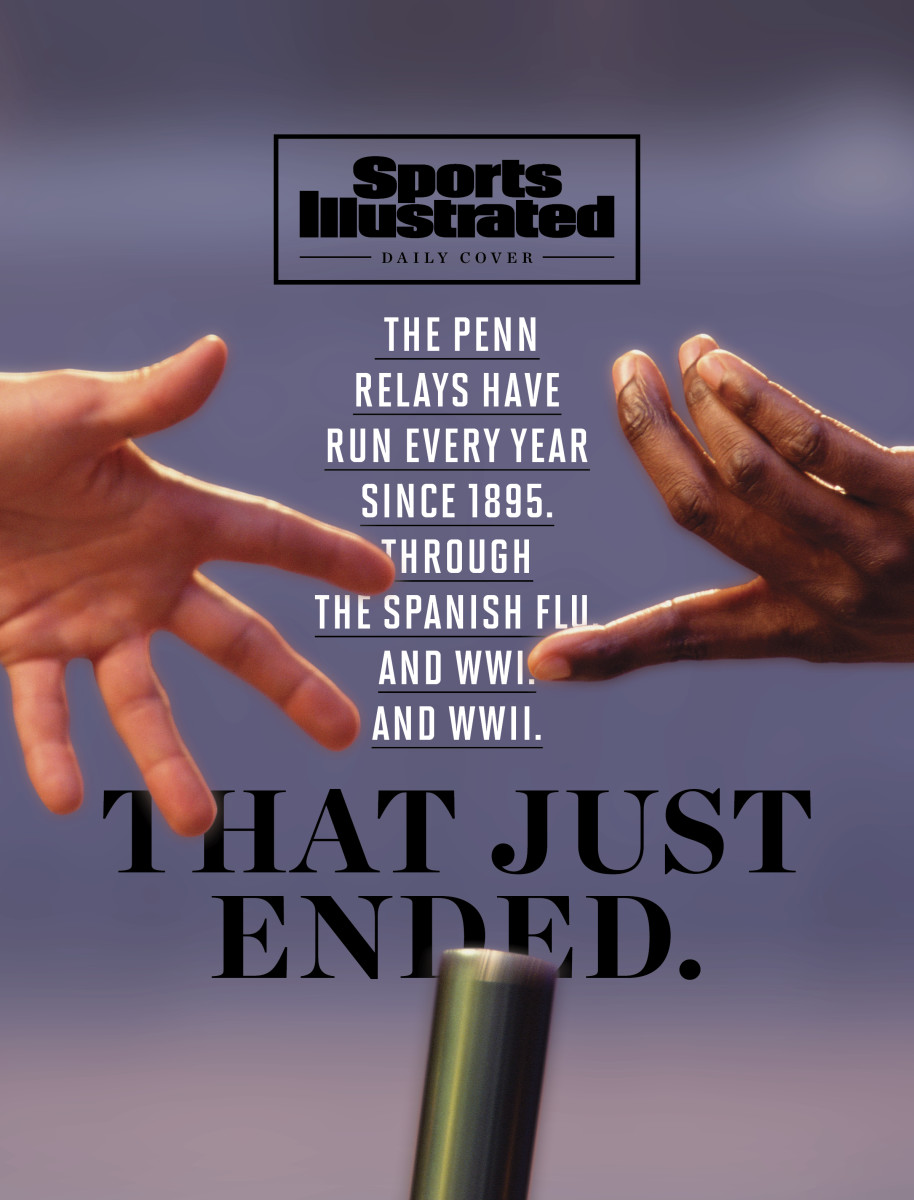

Surely that wasn’t the first time someone at the meet had run into this moral dilemma. Last April the Relays celebrated their 125th consecutive staging, a streak that endured through World Wars I and II without so much as a one-day postponement. Of course, that was before the coronavirus pandemic paused sports as we know them. “[In the past] we’ve escaped major calamities that suddenly befell the country,” says Johnson. “But the Relays have often been responsive to general societal changes, if you will, and this is a calamitous change.”

Under normal circumstances, 14,000 or so athletes; 500-plus officials and volunteers; and 100,000-odd fans would’ve attended the Penn Relays from April 23 through 25. Instead, the 400 gold watches, 3,450 winner’s medals and 144,000 runner’s bib safety pins that Johnson had ordered will be stashed away until next year. The madhouse will be empty. Franklin Field will be silent. “Without the Penn Relays,” Johnson said in the news release one month ago that announced a cancellation of the 126th carnival, “springtime in Philadelphia will not be the same.”

For a time, though, Johnson had been holding onto hope. Even after the Jamaican government barred its schools from traveling for the meet, and after the superintendents at the Maryland track hubs of Baltimore County and Montgomery County followed suit, his staff kept busy by tweaking the qualifying standards to account for new fields. University higher-ups eventually made the decision, leaving Johnson relieved it was out of his hands—but until then staffers around the office had been reaching back into history for signs of optimism.

“ ‘What about World Wars I and II? It has to be the same, right?’ ” Johnson recalls being asked. “Well, no. While there were similar national emergencies, they were not so precipitous that they shut things down. This is completely beyond the scope of what we faced in those war years.”

Even so, the 1910s and ’40s remain relevant to the legacy of the Penn Relays for other reasons. Without having persisted through those periods, when athletes ran the 4x440 and put the shot while bigger problems loomed outside Franklin Field, it’s possible that the carnival wouldn’t have become the crazed multicultural celebration that it is today.

* * *

Inspired by a novel concept introduced two years earlier at a campus track meet, where teams of four had run quarter-mile legs in succession, the inaugural Penn Relays were held on April 21, 1895, coinciding with the dedication of Franklin Field (future home of the NFL’s Philadelphia Eagles and, for a few recent years, an ultimate Frisbee outfit called the Philadelphia Spinners). An estimated 5,000 fans filled the newly built wooden grandstands that first year, while athletes from eight high schools and 10 colleges battled on the freshly coated cinder track.

Much of the attention was grabbed by the relay team from Harvard, which breezed to a 50-yard victory in the 4x440, and by a Penn football star named Arthur Knipe, who, according to The Times of Philadelphia, broke the state shot put record by 10 inches, “with absolutely no practice.” Otherwise, though, reviews were tepid. “The only particularly interesting and well-contested event of the regular programme,” wrote The Times, was the bicycle race, in which riders “fought a most interesting struggle for supremacy.”

Clearly the competition wasn’t even that fierce. Having arrived in Philly the previous evening, runners from Harvard and Cornell reportedly yucked it up at a campus musical-comedy show alongside their Penn adversaries, sharing a theater box decorated in Crimson and Big Red colors. Still, it wasn’t long before the Relays’ reputation grew. By March 1914, as a squad from Oxford set sail across the Atlantic Ocean to become the meet’s first international participants, the Times of London observed: “These races have come to be the most important inter-collegiate and inter-scholastic games held annually anywhere in the world.”

By then, several months before the outbreak of World War I in Europe, the event’s proper name had grown to capture the scene at Franklin Field: the Penn Relay Carnival, after the circus ring of tents that sprouted around the field’s perimeter, in lieu of locker rooms. The event, meanwhile, had positioned itself as an innovative presence on the U.S. track scene, becoming the first major meet Stateside to follow the example of the 1912 Stockholm Olympics in adopting the baton exchange over the old method of touching hands.

Even after the U.S. declared war on Germany in early 1917, leading to the likes of Cornell and Yale withdrawing their runners “due to the stress of martial preparedness,” according to The Daily Pennsylvanian, the carnival barely lost steam. Chilly weather limited fan attendance on that Friday, April 27, but an estimated 15,000 turned out beneath clear skies on Saturday to see Penn edge out Notre Dame in the one-mile relay while BYU high-jumper Charles Larsen—“the lad from far-away Utah” with “the elastic muscles” as The New York Times described him—bounded to a new Penn Relays record of 6' 5 3/8".

Any result from the weekend, however, ran second to what the Gray Lady referred to as “all the panoply of war.” American flags filled every corner of the stadium grounds. Two college bands belted out patriotic tunes instead of fight songs. A soldier battalion of Penn students, clad in khaki military garb, stood watch with “businesslike-looking rifles in their hands” and filled breaks between races by performing drills in the infield. A hearty reception was given to hometown hero Howard Berry, who won his third straight carnival pentathlon on Friday before announcing he was immediately withdrawing from Penn to join the Army Aviation Corps in San Diego.

All of which set up an even greater display of pageantry in 1918. Not only did the action regularly halt when troop trains rumbled past Franklin Field, servicemen waving out the windows as the crowd applauded their passage south. But hundreds of active soldiers, Marines and sailors—among them: Berry, returning to represent Camp Dix—were invited to compete in a full slate of special events on Army-Navy Day, including wall scaling, field drilling, a rescue race, a bayonet charge and a bugle contest. Charlestown Naval Training Station, perhaps buoyed by the freshness of arriving in town first and bunking up at the posh Colonnade Hotel, captured the half-mile marching relay, its members still decked out in service uniforms.

The novelty competitions were never repeated, but the Penn Relays were nonetheless stamped as a marquee weekend on the track calendar. “The meet has become the most important held any place in the world,” The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote that year, “and the only athletic meeting that can be compared with it is the Olympic championships, whose continuity has been broken into by the war." Two-day attendance totals throughout the next decade reflect this rise in popularity: 38,000 in 1920 . . . 50,000 in ’23 . . . 60,000 in ’26 . . . . So, too, in a roundabout way, does the infamous 175-yard dash final of April 28, 1928, when Franklin Field’s brick parapet crumbled beneath a sellout crowd’s weight and caused 100-odd fans to tumble (unharmed) onto the track, right into the oncoming runners’ path.

Today’s Relays pulse with similar energy, albeit with a much different look. Black athletes have competed at Franklin Field since the turn of the 20th century, establishing the Penn Relays as a truly open meet for all races, beginning with a local high school track star, the son of former slaves, named John Baxter Taylor. Johnson recalls once coming across an archival letter from the 1910s, sent by a Penn Relays official to a university administrator who was threatening to withdraw his school’s participation if African Americans were allowed at the carnival, basically telling the racist bozo to take a hike. That, says Johnson, "is the most significant document I think I’ve ever seen regarding the Penn Relays."

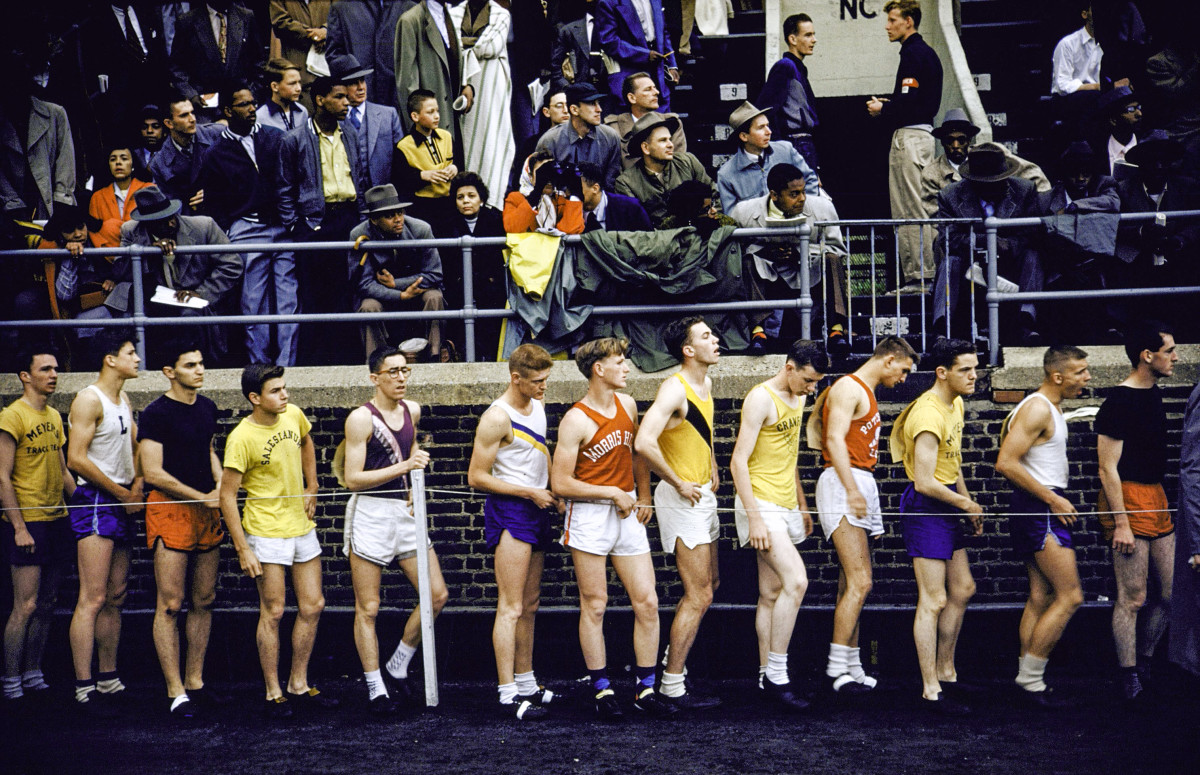

But it wasn’t until another global conflict broke out, decades later, that minorities began making their mark en masse. “Before that,” Herb Douglas says with a snicker, “it was all Ivy League.”

* * *

The young man tossed in his bed, fuming as the stench of hops filled his nostrils. A sophomore sprinter at the historically black Xavier University of Louisiana—“a school only half the 5,000 shirt-sleeved spectators at the 48th annual University of Pennsylvania relays could locate,” as proclaimed by the Associated Press—Douglas and his teammates had traveled to Philadelphia in April 1942 only to learn that no hotel would house them, “because we were a black school coming from the South,” Douglas says.

The closest lodging his coach could find was miles outside of the city, smack next to a brewery. “That’s all we smelled all night,” Douglas says. “I was so angry. It [made you] want to go beat the world. And that’s what we did.” The next day, with Douglas running leadoff in the 4x110-yard final, Xavier knocked off favorites Pittsburgh and Penn State to become the carnival’s first HBCU relay champion. “We were on our way as African Americans,” says Douglas.

Until then, black athletes had only occasionally made the papers for their exploits at Franklin Field; even Owens was upstaged in 1936, mere months before his gold-medal performance at the Berlin Olympics, when the University of Texas team arrived wearing 10-gallon hats to practice their starts. But these Xavier runners of ’42 were hailed as trailblazers on the track. “Brown America hit the jackpot with gusto here last weekend at the Penn Relays,” reported the historically black Pittsburgh Courier, under the headline “Xavier Leads Sepia Brigade as Race Stars Dominate Relays.” “In fact, it marked the first time any all-Negro institution ever crashed the sacred portals of the relay’s inner sanctum of championships.”

It was a banner weekend for breaking down racial barriers altogether. “Paradoxically, the event, once-upon-a-time strictly lily-white, has nurtured itself into the No. 1 Negro sports show of the year," the Courier wrote.

Though national rubber shortages and gas rationing had threatened to limit attendance, some 35,000 spectators watched Southern University’s Adam (Chu-Chu) Berry eclipse the meet’s old high-jump mark by a quarter-inch, while Douglas’s Xavier teammate Clarence Doak and Alabama State’s Leo Tarrant won gold watches in the 400-meter hurdles and 100-yard dash. Douglas recalls bolting out to a lead on his leg of the 4x110 relay and nailing his handoff to Doak, just like they had practiced every day, all season. “Shoot,” says Douglas. “I was going to bring that baton in there first if I had to die.”

Crossing the finish line in 41.7 seconds, though, Xavier’s sprinters were more funereal than festive. “Well, you take an all-white crowd. . . ” Douglas says, trailing off. “We were very cool about it. We shook hands, stood up for a photo, and that was about the essence of it.” The reception that awaited those sprinters upon their return to New Orleans was only slightly warmer. Invited to a theater screening of Pathé News covering the Penn Relays, Douglas got to watch himself run for the first time ever. “Everyone cheered,” he says. But: “We had to sit up in the [theater’s] bleachers, because that’s where African Americans sat.”

Over the next several decades, until SEC schools finally got with the times and integrated their track teams, “the athletic growth of the HBCUs along the Atlantic Coast was really what marked the 1950s and the early ’60s at Penn Relays,” says Johnson. Just look at the list of champions: Nine HBCU teams captured relay titles in the ’50s (including Morgan State, with its four straight wins in the 4x100-meter dash), followed by 15 more teams in the ’60s. Black fraternities and sororities, meanwhile, have been putting on a Penn Relays step show on campus every Saturday night after the final race, dating back at least into the '80s.

Based today in Philadelphia, Douglas, at 98, is believed to be the oldest living Olympic track and field medalist, having taken bronze in the long jump in 1948, in London, before pivoting to a successful career in the liquor sales business. It’s clear that he hasn’t lost his passion for athletics. “I jogged until I was 66,” he says. “I worked out swimming until just three months ago.” He also makes the quick trip to the Penn Relays each year, donning the gold hat of an honorary official in the same stadium bowl where he once helped make history. “If someone comes up with a complaint,” he says, “I take it to a young guy and let him handle it.”

As he sits there at Franklin Field, runners whipping past his post at the referees' table in the corner near the first turn, sometimes Douglas will peer into the stands, flags from European nations and Caribbean islands alike flapping in the spring breeze, and he will think back to April 1942. To the perfect baton exchange, to the all-white crowd, to the smell of hops. “We laid the foundation for African Americans. ... For the Caribbean as well,” he says. “I watched it change.”

* * *

Up until two weeks ago, June Griffith-Collison didn’t even know the Penn Relays had been canceled for the first time ever. Which is understandable. As the president and CEO of Community Hospital Health of San Bernardino (Calif.), she is responsible amid the COVID-19 pandemic for the well-being of 350 physicians, plus 1,400 other employees—not to mention a slow but steady ebb and flow of infected patients. “My goal every morning is to make sure my providers and my front-line staff stay safe, make sure they have all the personal protective equipment needed,” she says. “I think it’s going to be a joyous day when we come out of this.”

For now, Griffith-Collison, 62, fills her hours by making rounds throughout the hospital, ensuring that her staff is practicing proper social distancing and wearing masks according to protocol. Presumably, this is accomplished at a swift pace.

In April 1978, then a freshman hailing from Guyana and attending Adelphi University, June Griffith was the breakout star of the first Penn Relays to have a full day of women’s events, running a 53.3-second anchor leg on the victorious 4x400-meter relay team and winning the long jump. As with Johnson, the memories of that first carnival are still fresh. The warmup jog she and her teammates took through a rainy yet “vibrant” street festival outside Franklin Field, where vendors hawked arts and crafts and spectators welcomed them. The “thunderous applause” she heard upon entering the infield, and “the crowd right on top of you, yelling and screaming” as she tore down the final stretch to beat Morgan State by 2.7 seconds in the 4x400. “It was my responsibility to bring that win home,” she says. “I had to deliver.”

More than the glory, though—women hadn’t yet “achieved [the] status” of earning gold watches at the Penn Relays, according to the next day’s New York Times, so she took home two championship medals—Griffith-Collison remembers with fondness the Relays’ unique scene. “America has come a long way, but they’ve never been into track and field like Europeans,” says Griffith-Collison, who later ran the 400 meters for Guyana at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. “But at the Penn Relays it was always packed, always crowded. That was the only [meet] that came close to a European setting.”

She has been back to the carnival only once since college, coaxed several years ago by some former teammates who wanted to reunite. And that’s what it turned out to be, a reunion—not only with her fellow Adelphi runners, but also with a number of women against whom she'd once competed on that very track. "It surprises you to know how many of the ex-athletes are still engaged in the sport," she says. "That said something to me.”

Griffith-Collison stepped away from the running scene after giving birth to a son, Darren—the future NBA point guard—but she and husband Dennis, another ex-Adelphi sprinter, have slowly returned to their roots, attending the Olympics and the IAAF world championships whenever they can. Not long ago, Dennis suggested they add the Penn Relays to their regular circuit, for old time’s sake. Health care professional that she is, though, she cannot help but imagine how such a mass gathering would’ve spread the novel coronavirus if it had been staged as scheduled this weekend. (In the event’s absence, the university is hosting a Digital Penn Relays, centered around a virtual race set in the online world of Minecraft.) “There was no other choice but to cancel,” Griffith-Collison says. “The stakes were too high.”

Through it all, she remains hopeful—about a flattened curve, about a widespread vaccine, about a world brought back to normal.

“And one year from now,” she says, “I’m heading to the Penn Relays.”