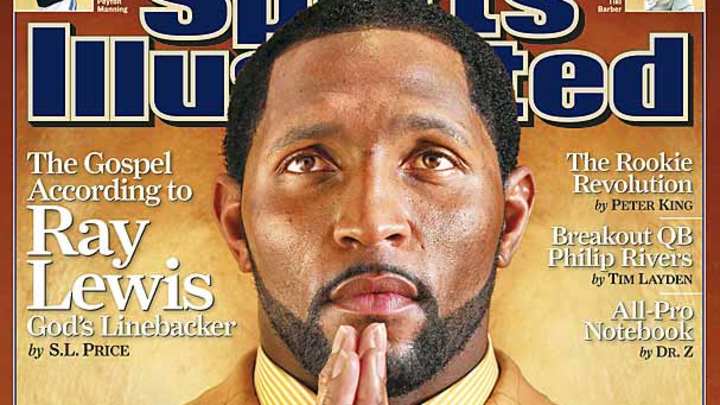

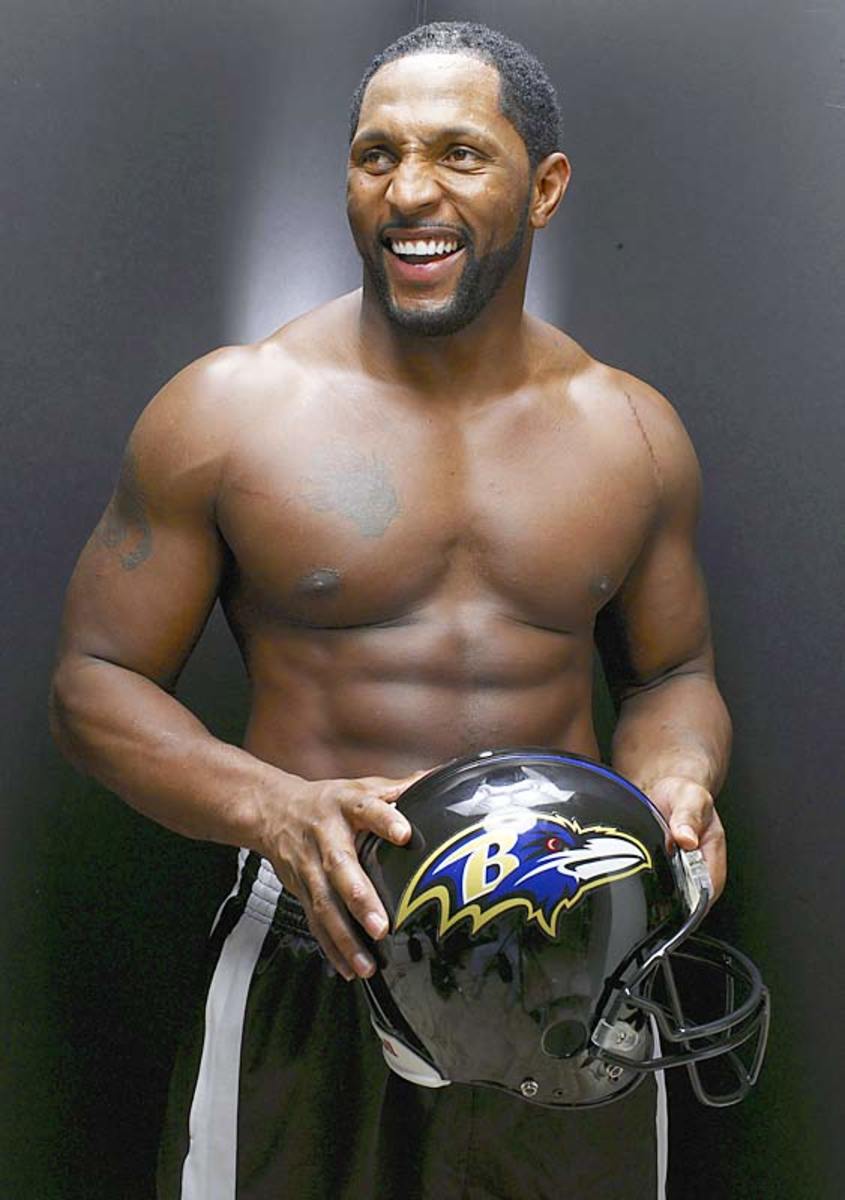

The Gospel According to Ray Lewis

The Gospel According to Ray Lewis

In this week's Sports Illustrated, senior writer S.L. Price tells the story of Ray Lewis, the Baltimore Ravens linebacker who was accused of murder one year and became Super Bowl MVP the next. What follows in this gallery are text excerpts and photos from a story billed in part as one of persecution and redemption, of fathers and sons, of pain caused and pain endured.

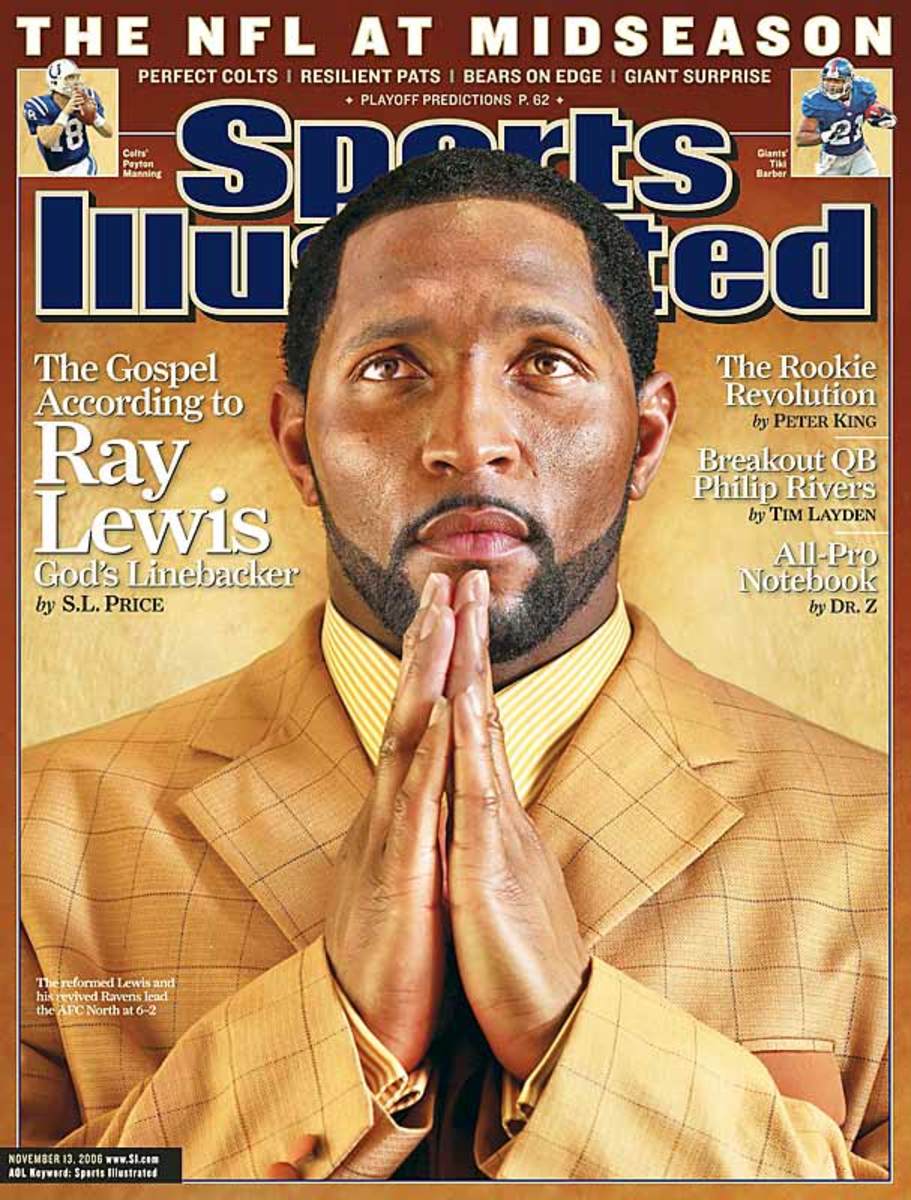

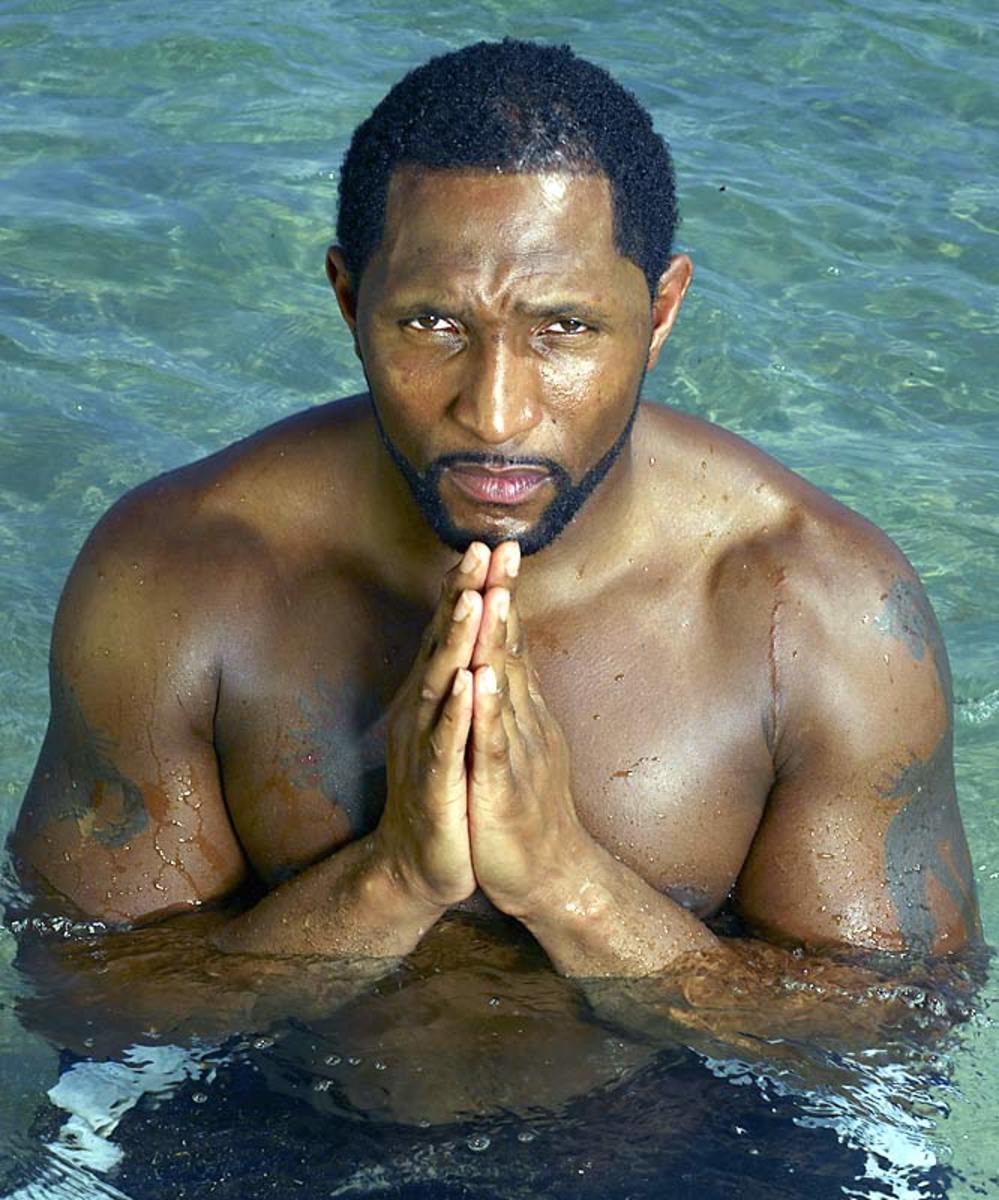

"God has done something in my life -- and not just for me to see it," Lewis says softly. Then his eyes flash, and he starts shouting, pointing. "God has done something in my life for ev-ery hat-er, ev-ery enemy, every person who said I wouldn't walk or ever play again!"

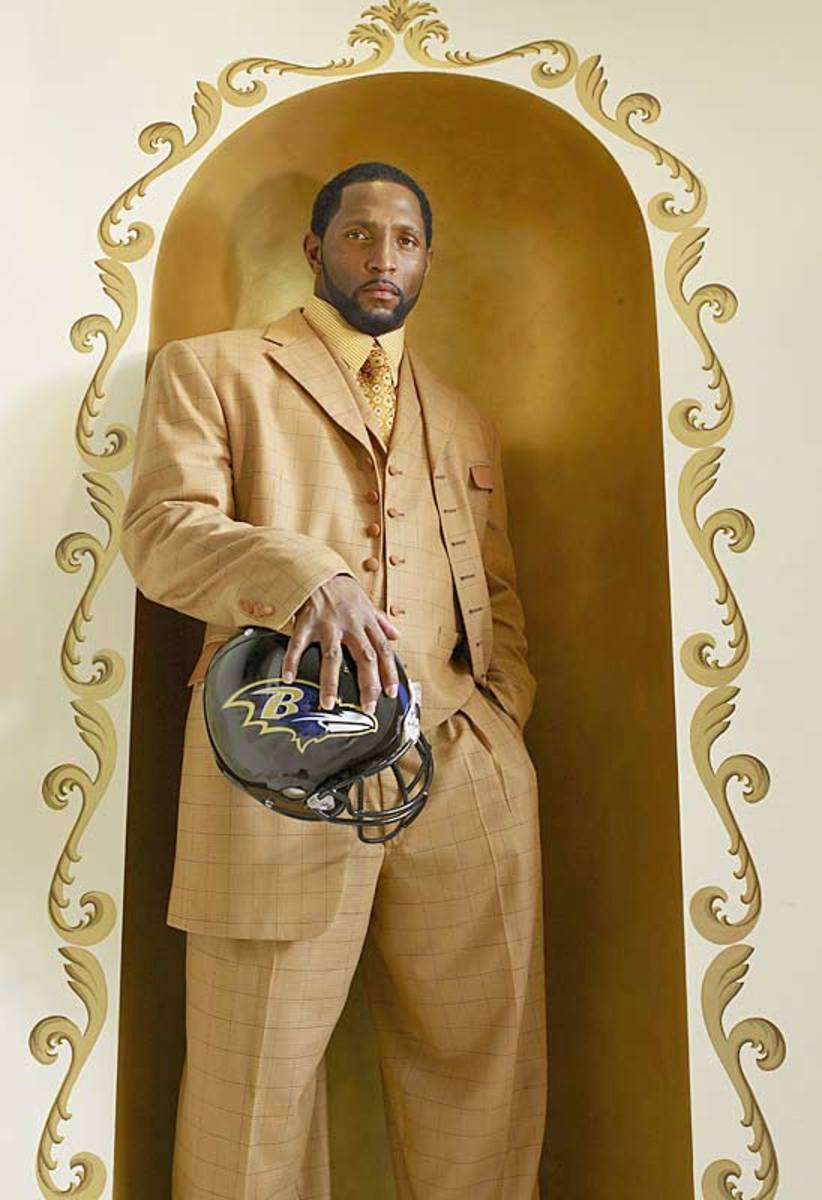

Lewis will tell you these days that he's "anointed," that he enjoys "favor," that he is a "king" charged with fostering a national ministry on the order of Martin Luther King Jr. and that, once football is done, his mix of piety and street cred and that spectacularly nasty, Court TV-chronicled fall will drag even the most hardened hearts to the light.

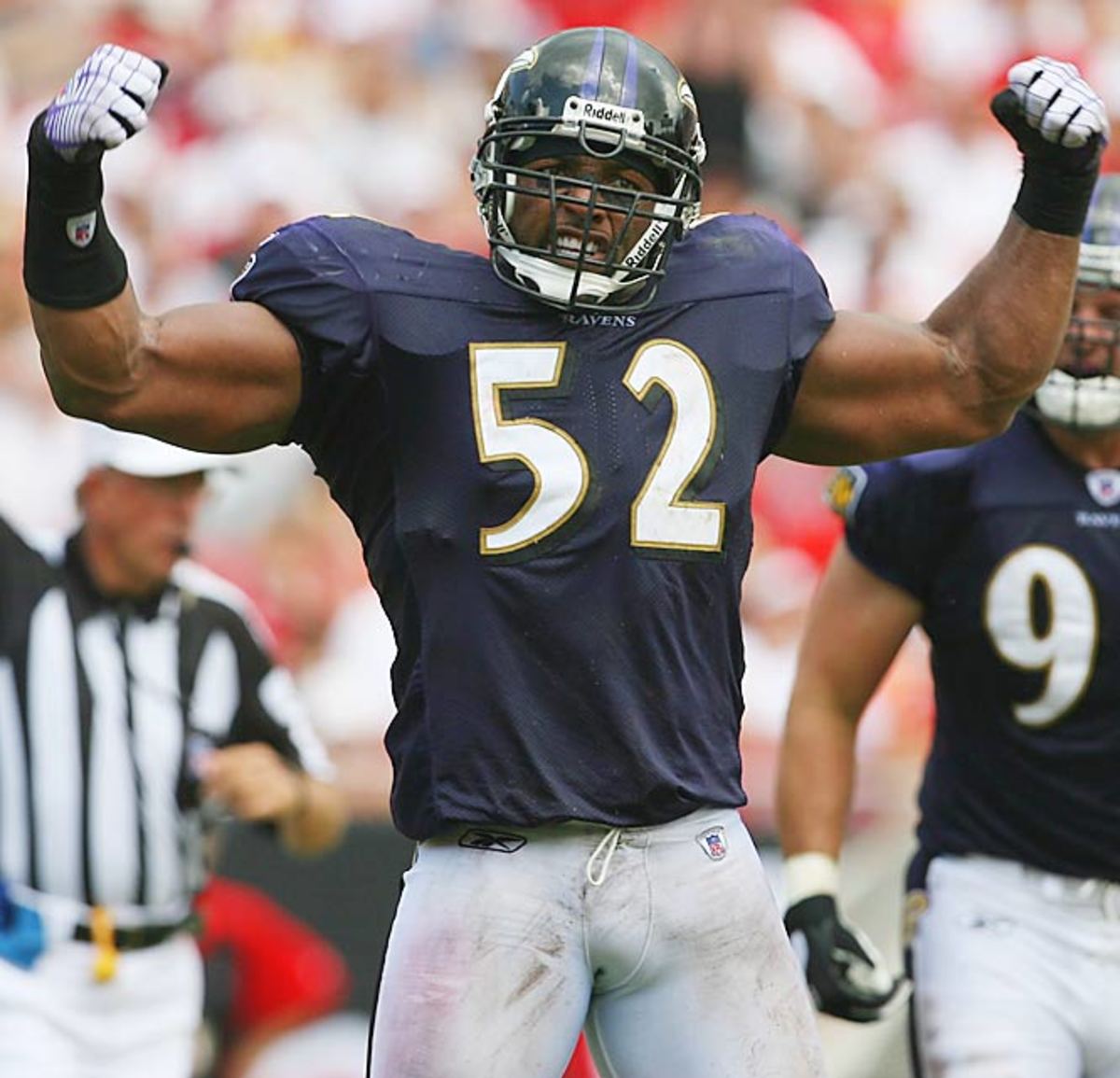

Lewis's revamped faith, like the man himself, is a raw, loud, electric thing, a muscular mix of the sacred and the profane. Every game day, just before another 60 minutes' worth of NFL hype and violence, Lewis will dip his fingers in consecrated oil, seek out a half dozen of his fellow defenders and trace a cross on each of their foreheads.

Lewis's charity efforts -- his annual donation of Thanksgiving meals to 400 Baltimore families, his purchase of Christmas gifts for 100 needy kids, his providing of school supplies to 1,200 city students -- have helped make him Baltimore's most-beloved public figure.

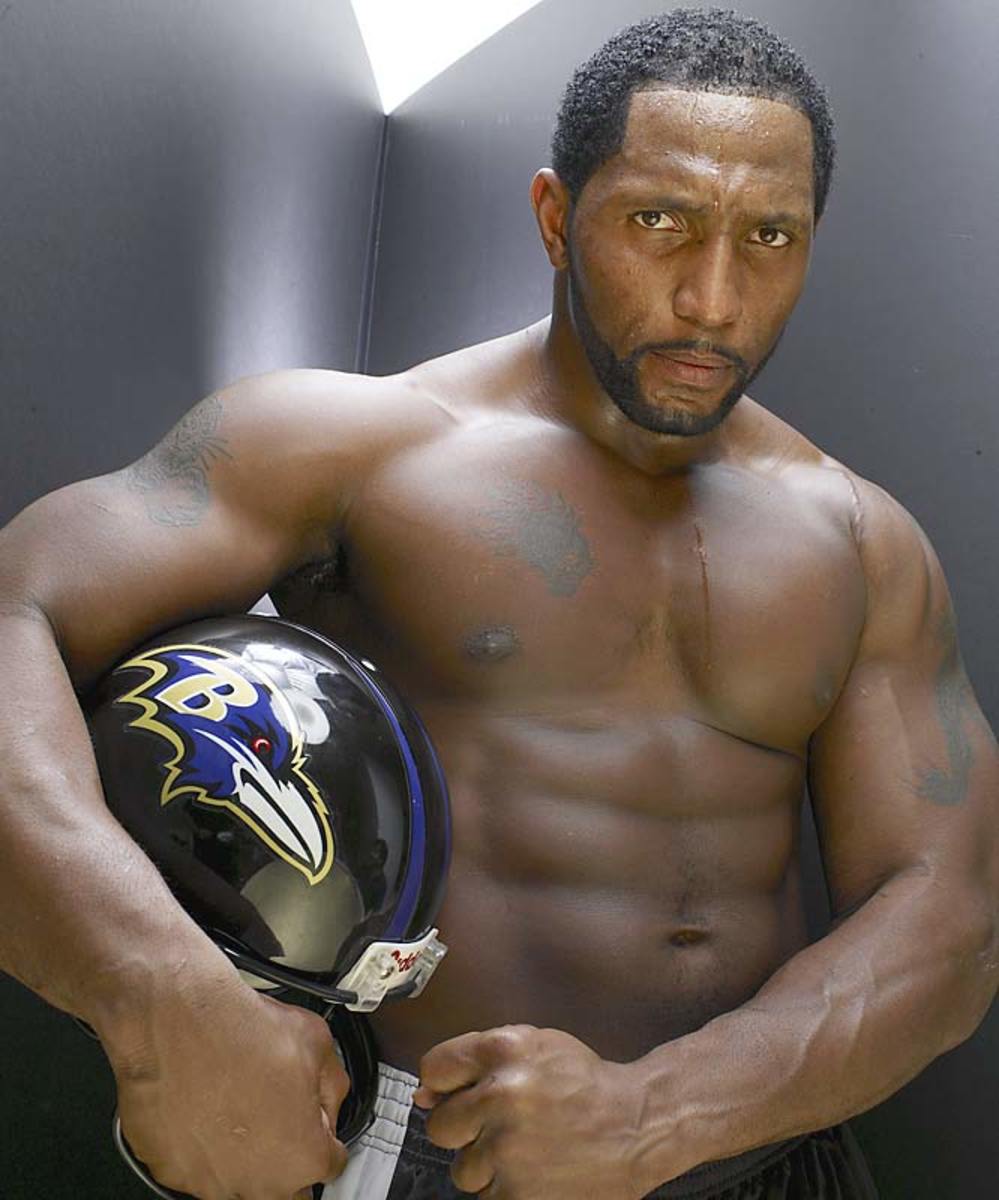

For all his spiritual growth these past few years, for all he will tell you about his new walk, it's clear now that Lewis retains every bit of swagger, menace, that palpable promise of violence that made him one of football's greatest defensive players.

The cynical will say Lewis bought his way back into favor, but it's not as easy as it sounds: Neither O.J. nor former Green Bay Packers tight end Mark Chmura nor any other recently scandalized athlete has come close to Lewis's recovery.

"Ray has a huge heart and will help anybody in need if he's able," says Tatyana McCall, who met Lewis at Miami and has three sons with him. "I would be remiss if I didn't say I was proud to be the mother of his kids. It's not always easy, but I am very proud."

The prosecution's case against Lewis fell apart quickly, and the murder charges were dropped. Lewis pleaded guilty to one count of misdemeanor obstruction of justice, was sentenced to a year's probation and testified in the case against two other men.

"The saddest thing?" Lewis says now. "Take me out of that equation, you got two young dead black kids on the street. The second sad part is, because of the court system and the prosecutor's lies, I got two families hating me for something I didn't have a hand in, and the people who killed their children are free. The people who killed their children could be having dinner with them and they'd never know. Because all they know is the big name, Ray Lewis."

Lewis won't go so far as to call himself the Second Coming, but he's close to believing himself a prophet of sorts, and if martyrdom is the price, so be it. "God has me to do what people are afraid to do: tell the truth," he says. "Yes, racism does exist. Hatred exists every day. I'm not afraid. The worst thing that could happen to me -- and I don't see it as the worst -- is to be killed and go to heaven."