Roberta Williams thinks it’s a shame gamers aren’t taught patience anymore

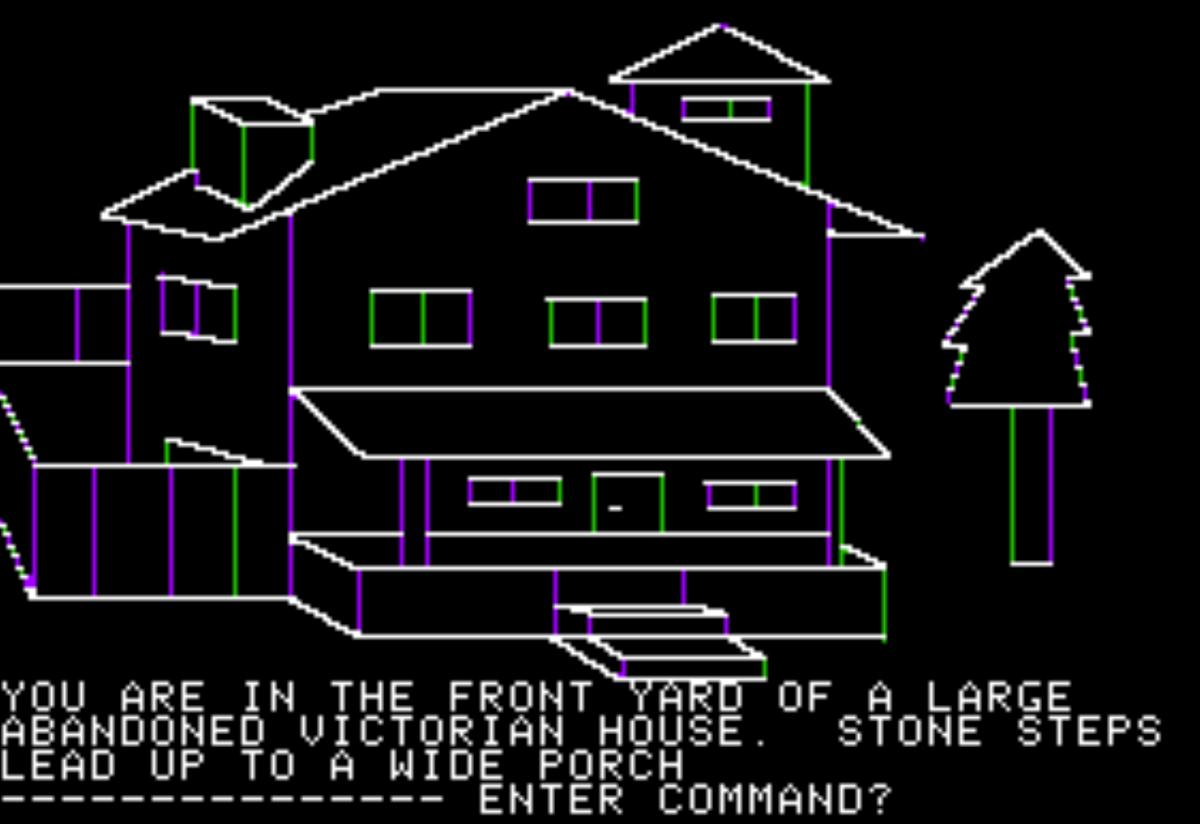

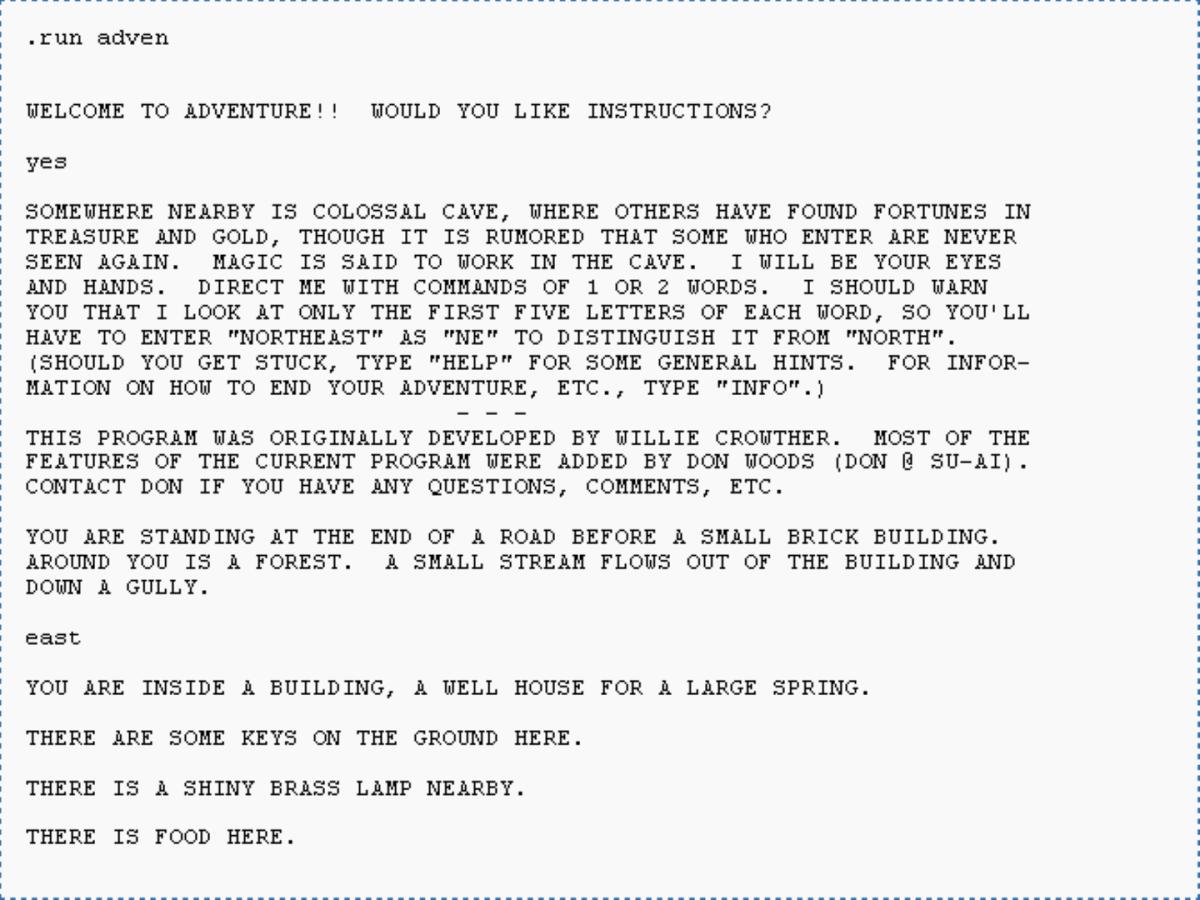

When you boot up your PS5 and start playing God of War Ragnarök, it’s hard to imagine that at one time adventure games didn’t have graphics. They didn’t have audio either. Back in the ‘70s, as video games were just beginning, adventure games were nothing more than text on a screen. You were given a problem, you typed in your solution, and the scenario that played out was all in your head.

There are few people still working in the industry that were there from the very beginning, and even fewer that were as influential as Ken and Roberta Williams. The pair founded Sierra On-Line, which developed, among other things, the King’s Quest series of adventure games, and published, or had a hand in making, many many more.

We were fortunate enough to speak with the Williamses about their time in the industry which has advanced beyond imagination over the last 50 years. Ken said it best himself when he explained, “We've been around the business from the beginning and watched it grow. It’s kind of a wild business that got a lot bigger while we weren’t paying attention.”

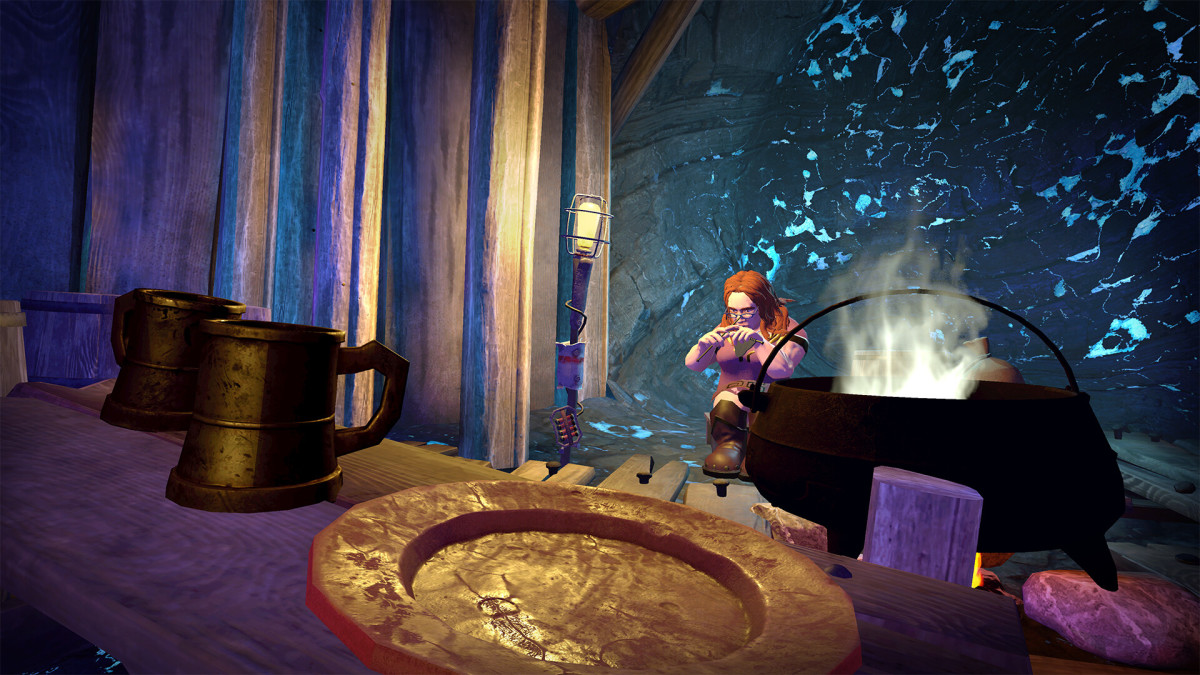

The couple took a 25-year hiatus from gaming, and have only recently come back to release their new game Colossal Cave, a 3D reimagining of the 1976 text adventure Colossal Cave Adventure. The original game had a huge influence on Roberta, and is the game that influenced her to design games for herself, starting with another adventure game, Mystery House.

Remembering Mystery House, Roberta explains: “I was just motivated to do it. In fact, I was almost compelled. That sounds very like it's a very mysterious word. But I was compelled to do it, to just sit down, never having designed a game in my life. Computer games were not common back then. I had figured that Mystery House would be a text because I didn't know of anything else.

“But Ken is a great programmer. He's a genius software engineer, and when I told him and showed him my game for Mystery House, I asked him, ‘Will you program it for me?’ So he agreed, but we started talking about [it] and he said, ‘You know what? We should put graphics to it.’ So that was his idea. This is on the Apple II [which] had no computer games with graphics at all, none at the time. So the idea of putting pictures or graphics to it as bad as they were, [and] they were pretty bad, it was a huge step in technology, believe it or not.”

The strides that the Williamses made in the gaming industry cannot be overstated. The couple both influenced how people took to designing or writing games, and the way they could be programmed or the different technology they could use. This was best demonstrated by their long-running series King’s Quest, which made huge strides with each new entry.

Roberta claims that improving on the series was easy, as advancements in technology told them where to go next. She says, “In those days, it [buying a new computer] was definitely every year. We used King's Quest as the technology advancement product. We had prototypes so we had some advanced knowledge. I would say, ‘Okay. What are the parameters for next year?’ Whatever it was that was going to be out, tell me what it is and I will design the game around how much memory and how many colors. Can we have animation or sound?

“I would design a game according to that. We had other designers and they would follow behind and use the new way that we decided that we're going to go and they would design their games around that, and then [again] two years later the next King's Quest. I would advance and we would move forward forward forward.”

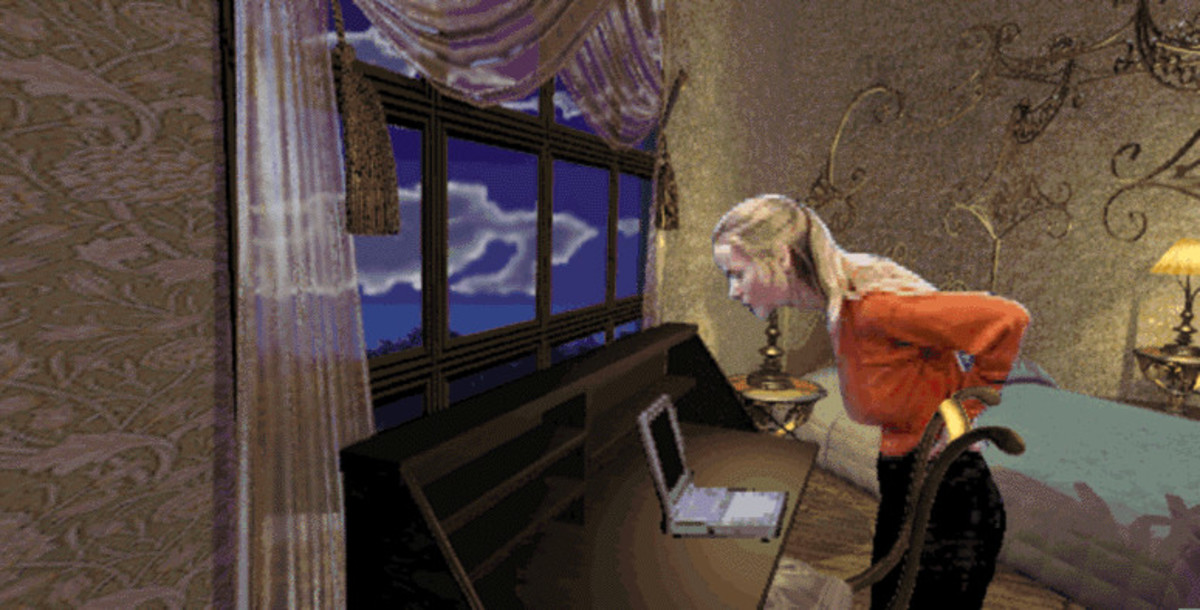

While adventure games were the basis for Sierra On-Line’s developmental success. Roberta is also known for Phantasmagoria, a horror game that had the team work with FMV for the first time. While FMV was already picking up in popularity, it wasn’t just the fad that encouraged Roberta to use it for her game.

Roberta explained her thought process for designing horror and suspense. She said, “I became interested, a little bit obsessed, in the idea that you can scare someone playing a computer game. I played both [Night Trap and The 7th Guest], and those were shot as movies, that you basically had like decision trees, and then you would watch vignettes. The reason I was looking at those at the time was I was trying to figure out how to scare somebody with a computer game.

“I was going to figure out what scares people, not just in a movie, not just in a book, but if you go out camping with your friends and you're sitting around a campfire and you start telling each other scary stories. I read Stephen King almost like a textbook on how to write a scary [story]. It got to the point where I started having nightmares literally. I would wake up screaming and I said okay, I think I'm done.

“You have to put yourself in the body of that actor [and] that can't happen with a computer-generated character. So I had to go with actors, but I didn't want to do the cutscene approach with vignettes that had been done up to that point. I wanted it to be done in the same way that I did King's quest and every other game as much as possible. We decided to do it with blue screen. The world was a 3D-rendered mansion and town and the land around was 3D-rendered. Walking was done on a treadmill, but we had to have her walk very naturally, then cut her out and made her a character. And I think it worked. A lot of people tell me they were literally scared.”

In the 25 years they were absent from gaming, I wondered what had inspired them since they stopped developing their own games. Technology has obviously advanced, but so has methods of storytelling, ways of making the audience feel. The Williamses didn’t seem concerned with inspiration, and instead went out on adventures of their own.

Roberta explains, “When we sold Sierra we had to sign a five-year [non-compete] deal. So we couldn't [make games], and there was no reason to [play them] in the meantime. We're very energetic people and we like challenges and I love adventure, whether I'm designing it or playing it or whether I'm doing it. And we decided that we were going to buy a boat that could cross oceans that we could handle ourselves and circumnavigate the globe, but we never got to Australia.”

So what made them come back after all this time? It seems it was pure curiosity. Roberta told me, “I think both Ken and I have been somewhat interested in getting back into the industry a little bit more [out of] curiosity. Like, I wonder what's out there and what we could do and could we do it and do we want to do it?”

However, the process of getting back into gaming seems to have been a difficult one. From the new interfaces, and game engines, software had moved on from what they once knew. They tell me that Ken had been playing around with Unity with the thought of making a game to teach beginners how to design basic game code. However, when Roberta suggested that they reimagine the game that got them started, Ken was on board.

The task wasn’t as simple as they first thought. Roberta explains the struggles they came across, “[It was] very hard, very hard. I thought it was gonna be easier because the game was already designed and it's very historical. It was the blueprint you might say for all adventure games. All we have to do is put graphics to it. I was told that retro was very in these days and point-and-click everybody loves right now. I approached it as I would have in the ‘80s, and we kind of wanted to get sort of an ‘80s vibe.”

Luckily, the pair had the original source code from Will Crowther and Don Woods, with notes interspersed between lines explaining why they made each decision for the games’ design. There was still a lot to be decided though, from the look, to the sound, to the actual gameplay. This is alongside all of the decisions that need to be made to make it more accessible for a modern audience.

The differences between players in their era, and players now is what surprised the couple the most. Roberta says, “I am finding that some players of today may not have the patience for it. I don't think it's too hard, I honestly think it's a patience thing. It's stopping and thinking and pondering and figuring out, taking time, writing notes. I think taking notes is not something that is normal in today’s world. It's very deep, you have to get really pretty far in the game to really start understanding it.

“In fact we had hired 35 people to help us and work with the game and they were all of probably your generation [millennials] and younger. But a lot of them came to us and basically said ‘We think this is going to be too hard for today's generation.’ We have automapping, we have a hint line, you can call the hotline, we're thinking of doing a hint book. But we are wondering if maybe we should do a little more hand-holding.

“It actually kind of saddens me, you want to know the truth. Having some thinking is a good trait. If you're figuring it out yourself and you have that moment where you click, that's so much more satisfying. It is like this really satisfactory feeling and maybe I just assumed that that was a very human trait. Maybe it's not. Maybe it's something that has to be taught in schools or by parents. We talked about it a lot in the media about how this game [the original Colossal Cave Adventure] wouldn't sell today. Isn't that sad? It's too hard for today's player, [but] it wasn't in the ‘80s, it wasn't too hard.”

Whether the Williamses will create another game after this one, all depends on how successful it is. They have a good understanding of who this game is for, but they still want to create games that can find their audience among today’s selection. Roberta told me, “It's not going to be a big hit. I think it's for a relatively narrow audience because of what it is, and it's not for everybody. And I think it's sort of being reviewed as if it is.

“It is a game for adventure game players. I always thought I knew what an adventure game was. I'm kind of the one that helped start the mystery adventure genre, so I thought I had a pretty good handle on what an adventure game is, but apparently not. It's a definition that has expanded, so that has made it a little bit tougher to take this game and make it be like what I think of as an adventure game, which probably fits into the 80s and 90s and the early 2000s [definition]. I always knew it was never going to be for everybody. Adventure games in and of themselves are not for everybody.

“They were for adventure game players of those days. I added a little bit to try to spice it up, but I couldn't go too far. Colossal Cave itself was self-limiting [with] what you can do. It's like walking on a fence. If I try to make it too modern and fit in all these elements, I would be in trouble with people that love the game. If I keep it very original, I'm gonna be in trouble with all the modern players. So my job was how do I make this game without making people mad? Obviously, I would like to capture as many as I can and have them try it out and see if they have the patience. I know they're out there, I know there are those out there that have the patience and would want to try it. Once it starts getting a little harder, keep going, keep pushing and keep trying, take some notes. It won't hurt you.”