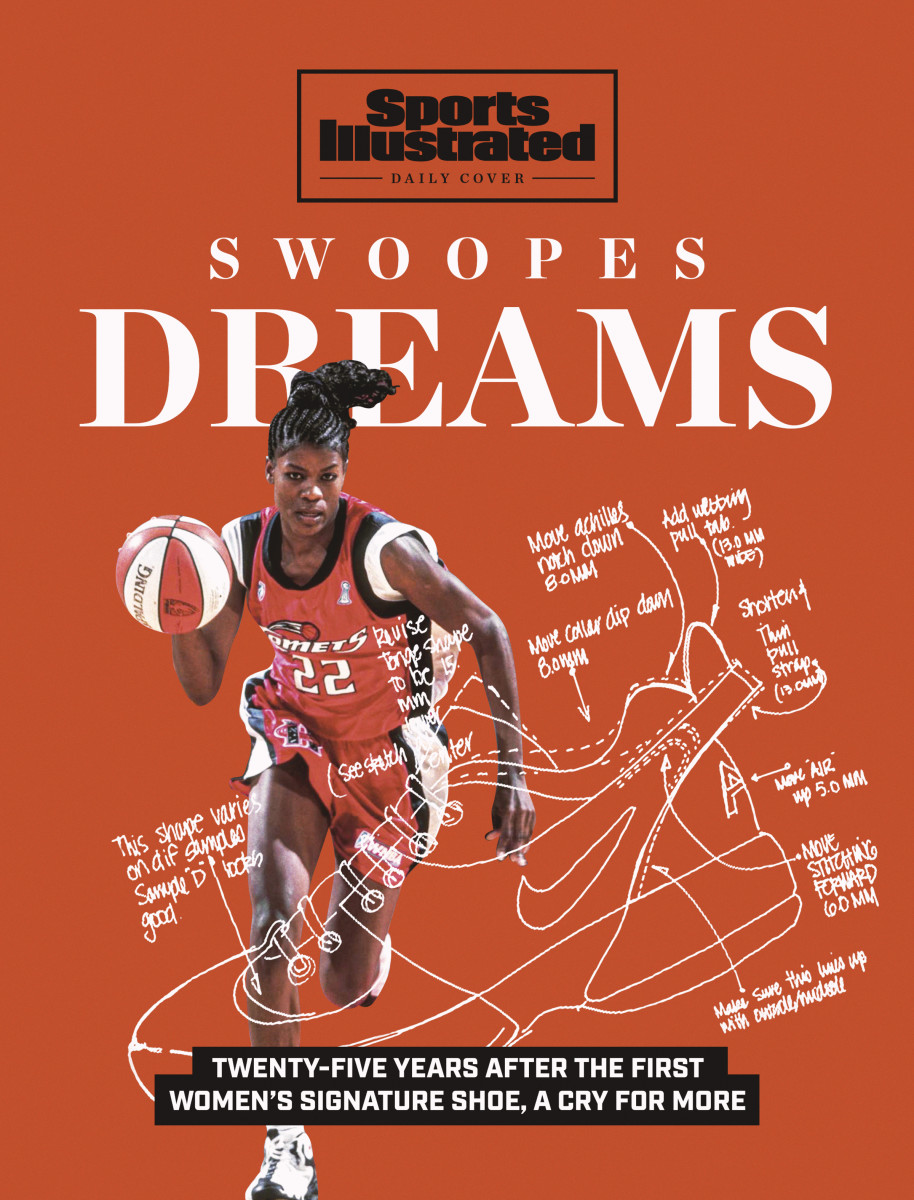

The Legend of Air Swoopes and the Quest for a New Women's Signature Shoe

Sheryl Swoopes never wore Nikes as a kid growing up in Brownfield, Texas. “I didn't even know what Nike was,” she says.

O.K., perhaps she’d heard of the brand, but she never wore the shoes, insists Swoopes. Her mother, Louise, raised four children on her own, and practicality won out over the latest footwear trend. Even in college, at Texas Tech, Sheryl wore a more affordable pair of Converse. As a senior in 1993, she won the national title in white-and-red Accelerator RS1 hi-cuts.

That all changed two years later, though, when Nike announced the Air Swoopes, just in time for the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta and ahead of what would be a groundbreaking year for women’s basketball.

From Texas Tech, Swoopes played professionally in Italy, but her career was short-lived. As is still the case for some players today, she was not paid on time, and so she decided to return home. Around that time, USA Basketball began paying its athletes year-round to train and play exhibition games against college teams on ESPN. The NBA financed marketing for the women’s team, placing it front and center for the first time. All of this served as a soft launch for an NBA-backed women’s league.

A quarter-century later, no sneaker has impacted women’s basketball culture more directly than the Air Swoopes—because there’s been no true successor. Undeniably, the women’s game has reached fantastic heights at the college and professional levels, but in terms of women’s shoes, the Air Swoopes is the most successful in history. Hoopers like Candace Parker, Maya Moore and Elena Delle Donne have had player exclusives over the years. Legends Rebecca Lobo, Dawn Staley and Chamique Holdsclaw have carried signature shoes. But none of those shoes had seven runs, like the Air Swoopes. “Do I think it's time for someone else to have their own signature shoe?” Swoopes asks. “Of course I do.”

The economics back her up. Women’s sports fans have shown that, largely, if Nike sells it, they will buy it. In the last year, the company saw its U.S. women’s national soccer team World Cup kit become the No. 1 selling kit ever sold, and overall World Cup–related apparel sales increased by 150%. In the fourth quarter of 2019 the company became No. 1 in market share for bras in North America for the first time in its history. Additionally, Nike saw a first-of-its-kind Sabrina Ionescu Oregon Ducks replica jersey sell out in less than 24 hours. Based on the success of the Iatter, “I feel like there could be a big push to make a [signature shoe] with [Ionescu],” says Melani Carter, a cofounder of the women’s sports and sneaker culture website Made for the W. “That’s the route Nike might want to take if they want to be on that history-making train.”

In June, Nike announced the Swoosh Fly athletic shoe and apparel line, designed with the women’s basketballer in mind—but at the moment there’s no specific plan for a signature shoe, despite a few candidates as deserving as Swoopes herself was.

***

Looking back, everything aligned perfectly for Swoopes. In 1993, she finished her Texas Tech career as the National Player of the Year, an NCAA champion and the record holder for the most points in a national title game, with 47, beating Bill Walton’s 20-year record by three. (Nearly 30 years later, that record remains untouched.)

In her preparation for a pro career overseas, Swoopes hired an agent. Nancy Lieberman-Cline billed her client as the “female [Michael] Jordan” in a 1993 interview with The Washington Post.

That summer, Jordan invited Swoopes to work at his youth summer camp in Illinois. The two played a friendly game of one-on-one in front of a crowd of campers and news cameras. Swoopes’s college career had caught the attention of those in the basketball community, and her casual banter with Jordan added undeniable mainstream marketability. The segment aired in the winter on NBC, soundtracked to “Anything You Can Do (I Can Do Better).” Even without a domestic women’s league, the newest Nike athlete was being introduced to a mainstream audience, right alongside the biggest name in all of basketball.

With Jordan retiring that fall for the first time, there was suddenly room for a new athlete to carry a signature shoe, and Swoopes got the life-changing news while meeting with staff from the footwear development team. Nike execs told her they were launching the first basketball shoe designed specifically for women, and that it would bear her name. She remembers only soft screams of joy escaping from her mouth.

The release was part of a new company commitment to women’s sports, including soccer. (Much as Swoopes and the national basketball team was headed to the 1996 Atlanta Summer Olympics full of hype, the national soccer team had won the ’91 M&M’s Cup and was preparing to host the ’99 World Cup, sparking an unprecedented interest in that team.) Girls under 18, it was estimated by the Athletic Footwear Association, made up 43% of scholastic basketball players at the time, but women's footwear accounted for just 21% of Nike's domestic revenue, according to The New York Times.

Liz Dolan, then Nike’s vice president of marketing, reported at the time that "one in three high school girls plays sports." But these girls—and professional players like Swoopes—defaulted to men’s shoes for their needs. Dolan said Nike “needed to make a women's basketball shoe to make sure [women are] viewed as equal."

Sheryl Swoopes was the solution.

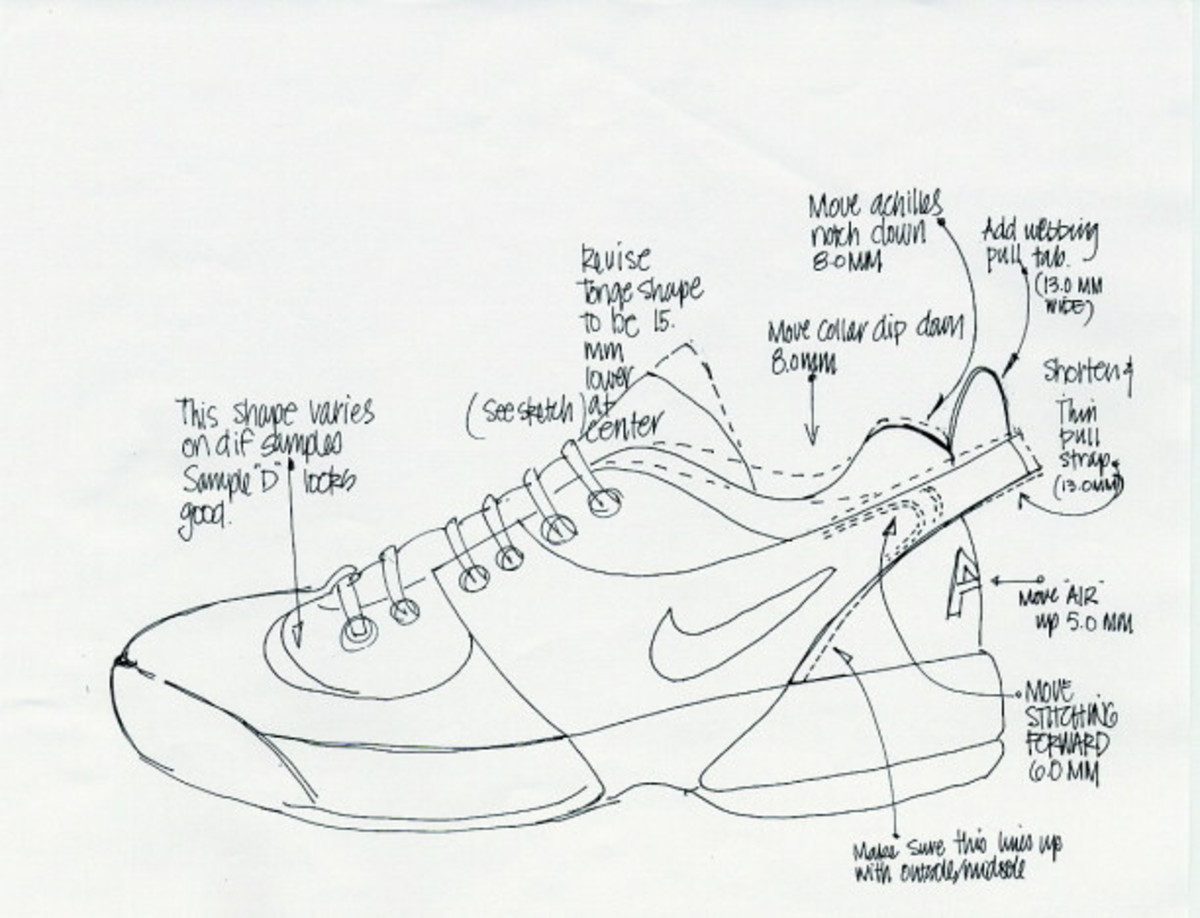

The lead designer on the Air Swoopes, Marni Gerber, worked closely with Swoopes to tap into what a woman might want from a performance shoe that she wasn’t getting from men’s styles. Swoopes said her main priority was proper support, so Gerber focused on designing a flexible, lightweight shoe that still provided adequate ankle support. In the end, the design incorporated a rugged black Durabuck synthetic leather material with a midfoot stability strap to cradle the foot, which had the added effect of color blocking, making the design stand out on the court.

The shoe also featured an “S” on the tongue, for Swoopes, and Sheryl debuted the original Air Swoopes during the Team USA tour ahead of the 1996 Games. The shoe came in black with a white strap, as well as in white with a black strap and blue swoosh. The pair Swoopes wore in Atlanta, where Team USA took gold, was white, with a red strap and blue trim.

“We had many meetings to decide whether or not we would call the shoe Air Swoopes,” Gerber says. “It was the right thing to do. Sheryl was the best player … at the time. Why wouldn’t we?”

***

Indeed, it was the right choice. Following Swoopes’s success in Atlanta—she started all eight games in her first Olympics and finished second on the team in assists (31) and steals (12), and was one of four players to average double digits in points per game—she became one of the first three players to sign with the new WNBA. Alongside fellow future Hall of Famers Cynthia Cooper and Tina Thompson, Swoopes led the Houston Comets to four consecutive league championships, a feat since unsurpassed.

Off the court, Swoopes helped spark a movement, and the rise of her shoe is indelibly linked with the rise of women’s basketball in the United States. The fast-growing girls’ basketball community now had its own role model—one who resonated specifically with Black and multicultural girls. The Air Swoopes, says Carter, was “a symbol, especially for women's basketball, that we had arrived. That shoe … garnered a generation of women and young girls who looked up to the game and wanted to play because she was that player. If you wanted to play basketball, you wanted to be like Sheryl Swoopes.”

Swish Appeal contributor and women’s basketball culturalist Jasmine Baker, who grew up watching Swoopes in her native Texas, remembers begging her mother to buy the shoes. “When I think about that shoe and what it represents,” she says, “I remember being a little Black girl seeing another Black woman—with my same skin tone, and my same hairstyles—hoopin’.”

Not all of those women looked exactly alike, of course. Those who were bigger or taller even found themselves competing with men for larger sizes, such was the demand. “I had men who wanted to wear [my shoe], but because they wore a size 13 or 14, they couldn’t wear the Air Swoopes,” says the three-time WNBA MVP. (The shortage of larger shoe sizes remained an issue when Nike did a retro run of the Air Swoopes II in 2018.)

If the Air Swoopes was a clear cultural hit, its monetary success is a bit harder to gauge. Asked about all-time sales of the Air Swoopes line, a Nike spokesperson said the company doesn’t share such details. Those who lived during the Swoopes era, though, can speak, if only anecdotally, to the shoe's success in the marketplace.

“They did not have the color I wanted in the size that I wanted. ... So I had to go to the next best color and hope they had it,” says Baker. “That was always the thing with women's shoes. ... I remember begging my mom for it and how difficult it was to get shoes in my size.”

***

Flash forward to the present, and Nike is once again looking to capitalize on an uptick in interest in women’s apparel.

A press release for Swoosh Fly—“Women are used to shopping in the men’s basketball section, with limited choices, and this widens her options ...”—mirrors what Dolan, Nike’s old VP of marketing, said in 1995 when announcing the Air Swoopes. The difference, says Mistie Boyd, a retired WNBA veteran and now the product-line manager for Swoosh Fly: This time around, there’s a cry from women for the product. All those years ago, Nike was just going on a hunch.

Boyd, who won a WNBA championship with the Phoenix Mercury, brings a certain viewpoint and legitimacy to the new Nike endeavor. She laments “just how underserved I was.”

Details incorporated throughout the Swoosh Fly line are designed to cater to women’s basketball players: hoodies with an extra-deep hood, to accommodate updos. Shorts with a triple-stitched waist, to eliminate the need to roll or tuck the waistband (an age-old trick used by athletes with trim waistlines and thicker legs to keep their shorts in place). Playing off a phrase from Nike’s launch in 1988 of its Women’s Air Force III shoe—Who said woman was not meant to fly?—the line will also incorporate the concept of flight through its signature cloud print.

Over the years, Nike and other companies have seen fleeting moments of financial success in women’s footwear and apparel. Today, Boyd says success is more about taking this moment and turning it into a movement.

“We have to get this apparel thing right. We have to gain some respect from our consumers,” she says. “Because if they say, ‘Yes, we love it; they're doing the right thing and this is ours,’ then it starts to open doors and create opportunities for players right now—[the same] opportunities Sheryl had back then.”

***

If there’s another women’s signature shoe in the offing, who could be tabbed as the face of it? Notably, both Ionescu and Las Vegas Aces standout A’ja Wilson—two young stars beloved by their old college audiences—consulted on the Swoosh Fly line, and Wilson is included in the marketing campaign. But there’s no shortage—especially now, as the players continue to lead on the court and in social justice efforts —of WNBA stars who could carry the next signature shoe.

Baker believes that Dallas Wings point guard Arike Ogunbowale qualifies, based on her performance (having twice reached the NCAA finals with Notre Dame, winning once) and her mainstream sports appeal (later appearing on Dancing With the Stars). Much like Ionescu, Ogunbowale shared a bond with Kobe Bryant. It can be argued that Jordan brought Swoopes to mainstream basketball; perhaps Bryant’s past blessing can play a similar role here.

College crossover success is important when considering a candidate for a signature shoe, but so too is an authentic voice. To that end, Carter, along with Made for the W cofounder Bria Janelle and general counsel Simran Kaleka, thinks someone like 2019 WNBA champion Natasha Cloud should get a signature sneaker. In June, Cloud became the first female athlete to sign with Converse, eventually joining NBA players Kelly Oubre Jr. and Shai Gigeous-Alexander in promoting the brand’s All Star BB Evo line. Later that month, she announced she would sit out the condensed 2020 WNBA season to focus on social justice efforts. (Converse later announced it would pay her ’20 salary.)

Elsewhere: Adidas collaborated with L.A. Sparks veteran Candace Parker on its Ace line. The shoe brand also has vocal All-Stars like Chiney Ogwumike and Liz Cambage on its roster. And Puma signed Phoenix Mercury point guard Skylar Diggings-Smith in 2017.

No matter which company takes on a women’s signature shoe first, though, Carter and her partners believe that any success will be predicated on the athlete getting the same level of marketing attention as any man with his own shoe. “The NBA does a great job formulating these personas. It's visible, you're gonna always hear about [their players],” Carter says. “Fans have not been able to access who these women are.”

Instead, the personality branding of female athletes more typically comes from independent outlets like Made for the W. Companies like Nike are still, woefully, behind the curve when it comes to tapping into women in sports and their impact on culture, despite their knowledge there is a market for women’s footwear and apparel.

During Nike’s 2019 fourth-quarter conference call, CEO Mark Parker reported double-digit growth in the women’s category in the last year. He added that women-specific sneakers like the Air Max Dia helped propel footwear and apparel sales.

Perhaps it’s not a matter of consumers responding to Nike, but Nike responding to the consumer. Says Janelle: “It comes down to, What do you value? Finally [companies are] starting to [understand] an ounce of what people value.”

It’s been two months since Nike announced its Swoosh Fly initiative, the latest dip into targeted women’s apparel. Maybe Nike—or another brand—will respond to one of its steadily growing consumer markets and finally launch what’s been more than two decades in the making: a new women’s signature shoe.