Don’t Look Away

Let’s start here: my house, a couple of months ago, a good friend over for dinner and the conversation turning toward the article you’ve just started.

This friend played sports at a high level, and he asked me, tentatively, whether he could explain why he doesn’t watch women’s sports. “Of course,” I said. “Let’s hear it.” I wanted nothing more than to understand why someone like him—an athlete, a millennial, a feminist—had never turned on a women’s basketball game. Or, more precisely, I wanted to hear why he believes he hasn’t.

“I’ve actually thought about this a lot over the years,” he said. “Because I often feel some level of guilt about it, but when it comes down to it, I just think that if I’m going to take the time to watch sports, I want to be watching them at the peak of how they can be played—speed, strength, all of it. And to me, that pinnacle is happening on the men’s side.”

I nodded as my friend spoke. He hit all the expected notes. I don’t watch because they can’t dunk; I don’t watch because they’re like a good boy’s high school team; I don’t watch because, you know, I could probably beat them one-on-one.

Perhaps you even saw your own reasoning reflected in his. At its heart, this reasoning insists that people don’t watch the WNBA because men run faster and jump higher. That is, in fact, true. Most men do run faster and jump higher. And, yes, it’s incredibly exciting when one of those men runs fast and jumps high and we watch, in awe.

It’s a soothing rationale, this little story we tell ourselves about our insatiable appetite for windmill jams. It’s foolproof, too, because this reasoning doesn’t just absolve sports fans of any further introspection, but more important it absolves the marketers, the TV networks and the sports apparel companies. Hell, it even seems to pardon the women themselves: It’s not your fault; sports fans crave something you just can’t give them. This reasoning presents itself as more than logical; it’s biological.

Actually, it’s pathological. It’s chronic, and irrational, and it’s been stalking the WNBA since its founding. In the U.S., this lie is the serial killer of women’s professional leagues. To name a few: the American Basketball League (1996–98), the Women’s United Soccer Association (2000–03), the Women’s Professional Softball League (’97–01) and Women’s Professional Soccer (’07–12).

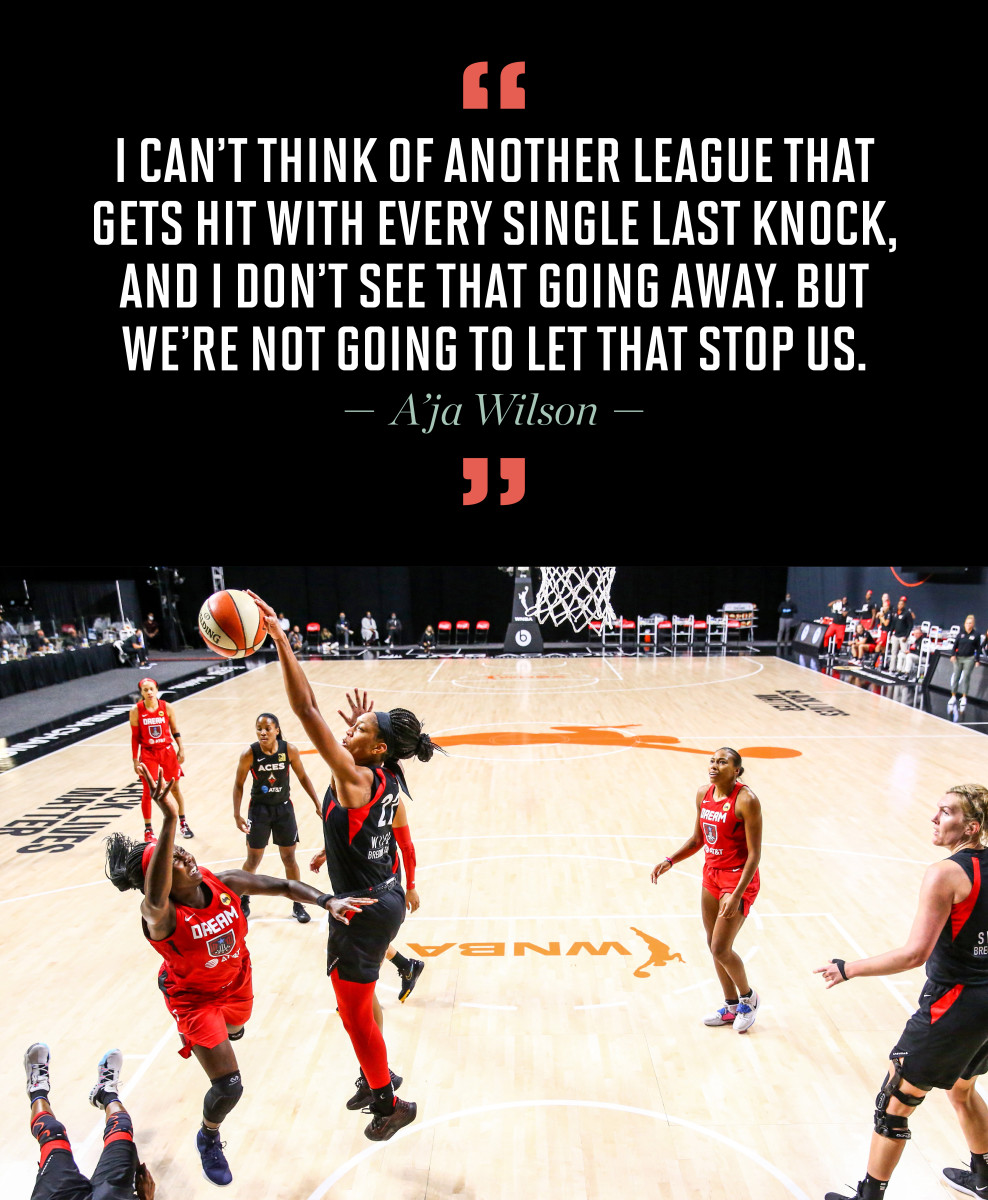

The WNBA, though, is resilient. When launched in 1996, the league was ahead of its time—in almost every way. Long before Big Business saw the value, the players of the W stood against racial injustice, and for equality, and took the hits—“Every direction we turned, we were walking into a wall,” says WNBA legend Sue Bird—for representing the folks at society’s margins. “People think you’re supposed to look and talk and be a certain way, but the WNBA blasts all of those things out of the water,” says A’ja Wilson of the Las Vegas Aces. “And you should want that. We are standing on the shoulders of women who didn’t back down just because casual sports fans didn’t think they were worthy. That’s what makes our league better, because we have faced those hurdles. I can’t think of another league that gets hit with every single last knock, and I don’t see that going away, but we’re not going to let that stop us.”

Understanding why we watch sports isn’t just a thought experiment. It has practical implications. Rather than passively believing the WNBA is biologically inferior, we can actively recognize that no athletes in modern history have faced more cultural obstacles than the players of the W. Not only are comparisons to the men ubiquitous—and the differences rendered clearer because of the unique intimacy of the sport—but also, more important, no women’s league has a higher percentage of Black athletes, meaning that for nearly a quarter century the WNBA has been rowing against the headwinds of racism, sexism and anti-LGBTQ sentiment.

Here we are, on the WNBA’s 25th anniversary, and society’s margins have reconfigured themselves. Today everyone inside the league feels similarly: that the world has finally caught up, that a movement has met its moment. In 2020 the WNBA saw all meaningful metrics—social media impressions, TV ratings, merchandise sales—skyrocket during its bubble season, and just months after the players signed a new collective bargaining agreement that doesn’t just raise salaries but encourages player movement, the fuel for year-round relevancy.

You might be wondering why, on this historic birthday, I’m not taking you on a trip down memory lane, peering into long-ago memories, spinning an orange-and-oatmeal ball as we backpedal to 1996. (You can see that here.) The league, its foothold and its future, has never been guaranteed, so why not simply celebrate a milestone reached?

For one, because public reminiscing translates only if most people agree that something matters, and, as a culture, we haven’t yet agreed the WNBA matters. But also because I think sports fans are ready for more context, more critical thinking about what drives their interest, as well as a league’s growth. It’s time. That aforementioned exchange, the one from my house? It’s not an anomaly. Some version of that exchange has played out millions of times—in cars and bars and coffee shops, among people of all genders and ages, in every year of the league’s existence.

A quarter century ago, a group of stakeholders—led by former NBA commissioner David Stern—believed the media exposure from a successful 1996 Olympics could serve as a springboard for the larger goal of launching a newly formed professional basketball league, with the backing of the NBA. From nothing to something, it was an inflection point for the game unlike any seen before, or since.

Until now. The promise of this second inflection point for the WNBA is to take it from subsisting to thriving. The league has finally captured a slice of cultural relevancy, and, if you’re just casually paying attention, you might believe the outcome, this potential leveling up, will be determined solely by the players of the WNBA. You might believe some line about quality of play, etc. etc.

But you’d be wrong. Here, I’ll give Bird the floor: “The story of 25 years, for a lot of people, the headline is: Oh, they wouldn’t exist if the NBA didn’t keep them afloat; look how poorly they’re doing. But that’s not the story line. It’s actually look at corporate sponsorships, look at the media: You didn’t invest, you didn’t do s---, and we’re not just still here. We’re actually growing.”

So let’s invest. After a quarter of a century, perhaps we finally owe the WNBA a little introspection.

The simple fact that in the last two decades Diana Taurasi has not blossomed into a transcendent megastar is evidence enough that our sports world is not a meritocracy, as we like to believe. Anyone who’s watched Taurasi play—or walk onto the court, or sit on the sidelines, or be anywhere, really—knows that she’s impossible to look away from. She’s won four gold medals with Team USA and three WNBA titles with the Phoenix Mercury, and her popularity (outside of Phoenix) probably peaked in 2004, while playing for UConn. “I don’t know if there’s a bigger marketing ball that’s been dropped than us not talking about Diana Taurasi nonstop,” says former player and longtime ESPN analyst Rebecca Lobo (whose husband is a contributor to Sports Illustrated). “Her name should have been like Serena Williams. It’s not that great players haven’t existed in the league; it’s that we haven’t done right by them. Taurasi should have been on national TV every week, and we should have been talking about her across the network.”

Lobo is getting to the heart of the matter. The heart of why we really watch. What drives our interest in sports, generally, are stakes and story lines. The stakes cannot be artificially constructed; they must be culturally agreed upon. Winning this game, this trophy, this tournament matters in some larger sense. An incomplete list of those we’ve agreed have significance: a title in any of the major sports (men’s, of course), an NCAA championship, the Grand Slam tennis tournaments, the Olympics, the World Cup. Regardless of the discipline, we’ll passionately watch any Olympic event. We’ll watch curling, and we’ll care, because an Olympic gold medal is at stake and we are patriotic.

There are other events on the “matters” list, but a WNBA title is not yet there. It is for some fans, of course, but it hasn’t so far hit a widespread cultural tipping point.

Go ahead and test this stakes-and-story-line theory. Imagine watching two lousy basketball players in a game of H-O-R-S-E. Yawn, right? Now imagine Mark Cuban walks by and announces that he’ll give the winner a million dollars. Well, now pull up a chair and get the popcorn ready. You might even start to feel your heart pounding, and you don’t know these people. And they’re not even good! Now imagine one of the shooters is your wife. Imagine if she wins this game, you know she’ll finally be able to pay off her college loan debt and start that business she’s always dreamed of. Bingo: stakes and story line.

Just existing in our culture, we absorb, almost through osmosis, a half dozen NBA story lines. In Pixar’s recent movie Soul, there’s a joke built around the perennial ineptitude of the New York Knicks. Men’s sports will invade our personal space, often without permission: Apple TV will literally interrupt whatever show you’re streaming to alert you that a game is close. You might stop and watch a couple of minutes, and probably not because some proficient skill thrilled you.

The WNBA might actually flourish if, just existing in our culture, the message we absorbed about the league was neutral, or even nonexistent. But it’s not. The league isn’t even afforded the common courtesy of apathy, which would allow curious, prospective fans to make up their own minds. Instead, the W is the butt of pathetic jokes, poorly written Saturday Night Live skits and aggressive trolling on social media. In this culture, when you’re not even seeking it out, people will invade your space to tell you how pathetic the WNBA is. That’s the story line absorbed through osmosis. So the W is forced to battle just to reach the starting line, just to remove the poison from its water.

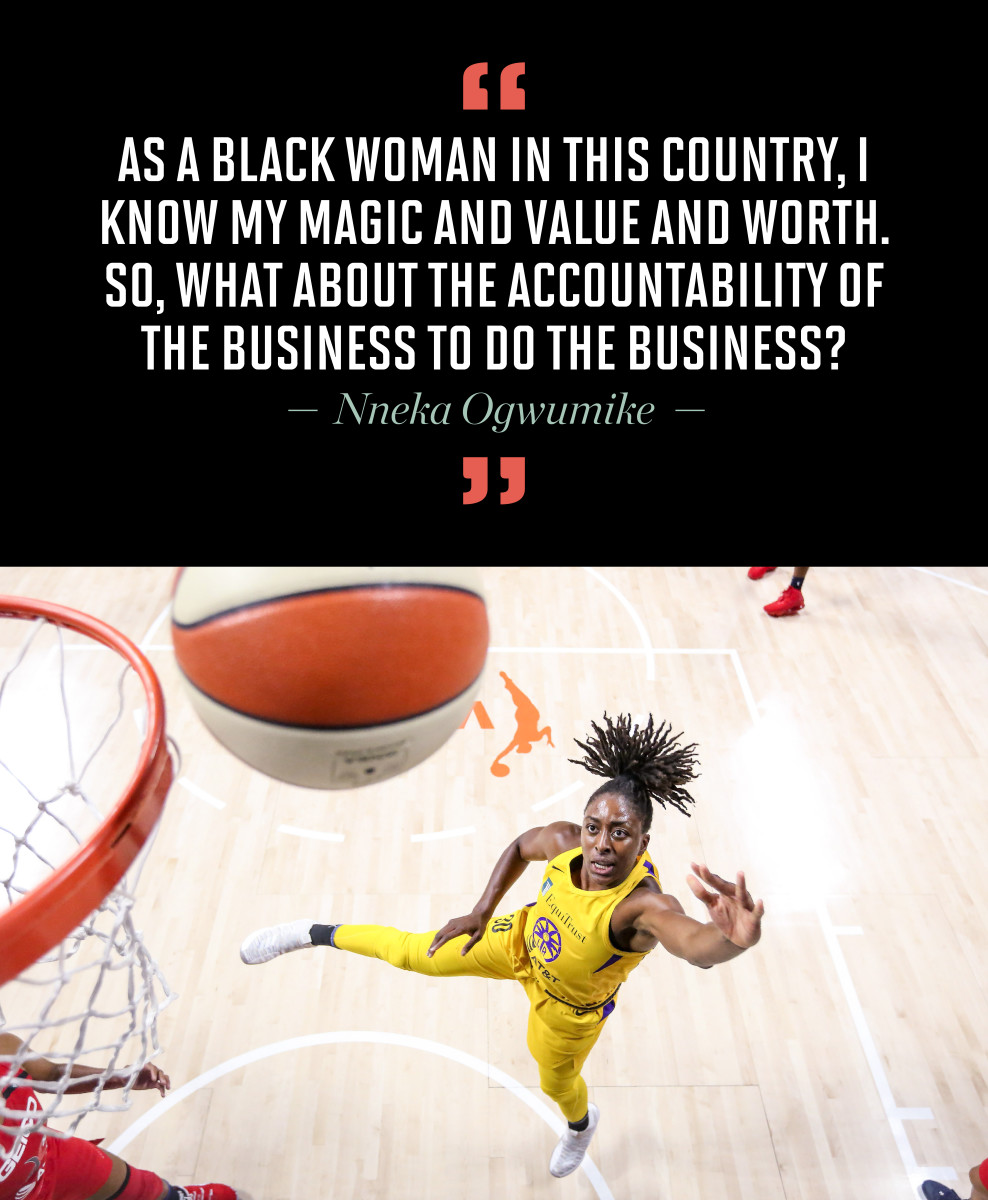

“When I hear the argument of ‘quality of play’ or shooting percentages—or points scored, or whatever—as reasons people don’t watch, those are all just excuses to continue pointing to the players, to the women, as scapegoats,” says Nneka Ogwumike, president of the players’ union. “When do we look elsewhere? As a Black woman in this country, I know my magic and value and worth. So, what about the accountability of the business to do the business?”

Every square inch of the NBA has been, or is currently being, exploited—physically, digitally and financially. Innovators offering even the slightest advantages—some small data insight, juicing beets for better oxygen absorption, creating secondary revenue streams by selling game-worn uniforms or the right to “own” a digital highlight—are rewarded with Wall Street–level salaries. Where there is cash, talent follows. So, in a world like this, what is the WNBA but, at best, a stepping-stone? Generally speaking, if someone is good at their job in the W, they move on. The NBA is the best 450 players in the world, surrounded by the best marketers, merchandisers, communications directors, salespeople, trainers and analysts. With few exceptions, the same cannot be said for the W, except for the part about the players—they’re the best 144 in the world.

Armed with all that information, fans can continue believing the WNBA flies below the radar because its players don’t fly above the rim. Or fans can glance at the infrastructure of the sports world—i.e., the programming decisions by ESPN, the marketing dollars budgeted by Nike, the cover (and coverage) decisions by the magazine you’re currently reading—and wonder whether perhaps, maybe, women aren’t invested in the same way men are. “If something is supported—monetarily, or in love, or in going the extra mile—then success is going to happen,” says former WNBA star Dawn Staley, the current coach at South Carolina. “If we pour into the W what they poured into the NBA from Year 25 to 50, we’ll have a team in every city and we’ll fly charter, and we’ll have sneaker contracts that are multimillion deals.”

During the pandemic year of 2020, ESPN more than doubled its slate of regular-season WNBA games, airing 37, up from just 16 the previous season. (The network was desperate for live programming.) It was an experiment that many women’s sports advocates had long called for. The old Field of Dreams argument: If you build it, they will come. More airtime would drive better ratings, would justify more airtime, would drive even better ratings. “A huge thing for us is breadth of coverage,” says WNBA commissioner Cathy Engelbert. “That ratings increase was because we had more games on and people would say, ‘Oh, it’s just because you had more games on’—as if we didn’t earn it. And I said, ‘Well, isn’t that the point?’ ”

“I’m not in the TV business,” says Seattle Storm guard Jewell Loyd, “but I feel like it’s not that hard to put us on TV. It’s an effort thing.”

You know Aristotle’s notion, The whole is greater than the sum of its parts? Somehow, when it comes to the first 25 years of the WNBA, the whole has been less than the sum of its parts. That is to say, all of the league’s tangential stakeholders profess dedication to the growth of the game. All the outward noises from such companies tell the story of sport as universal, of game recognizing game. The bird’s-eye view shows companies trading on equality; yet their day-to-day decisions rarely live up to those lofty ideals. Nike hasn’t introduced a new signature women’s basketball shoe in 25 years, since Sheryl Swoopes debuted the Air Swoopes in 1996. ESPN pays $12 million a year for the right to broadcast the WNBA, then historically buries games while offering almost no studio programming to generate story lines and interest. And for the upcoming 2021 season, ESPN has split the difference, dropping to 25 games. “My wish is that ESPN would drive the push for the WNBA instead of waiting,” says Lobo. “I wish we would drive the conversation. The WNBA has gotten cool, and ESPN needs to understand that it’s a cool thing.”

(If you’re doubting the WNBA’s growing cool factor, especially among the younger demographic, you’re probably looking in the wrong places. The evidence exists on social—Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok—where images of the players’ fits (i.e., outfits) as they walk into the arena get tagged and linked and reshared. In this way, players of the W are burgeoning fashion icons. “We were once seen as outsiders,” says Bird, who this winter was on the cover of GQ with her fiancé, soccer star Megan Rapinoe. “But society caught up with us.”)

A March 2021 study by USC and Purdue analyzing sports media coverage shows, once again, that female athletes receive about 4% of airtime on SportsCenter—about the same as it’s been for decades. Cue the chicken and the egg: Is the WNBA given little coverage because people don’t want it, or do people not want it because it’s given little coverage?

“People in every other industry understand that demand is created by the marketers and the decision-makers,” says Nefertiti Walker, professor of sport business at the UMass–Amherst. “They know: People watch what you tell them to watch, what you create bells and whistles around them watching. Only sports people, when making decision about investing in women, throw up their hands and act like the consumers drive decisions.”

The wild thing is that even that 4% actually overstates the coverage given women. Because that 4% is almost always either a highlight or an anomaly (i.e., the much-publicized on-court fight involving the Detroit Shock in 2008). It’s a one-off. It’s almost never a story line, which offers continuity, which sparks debate, which has elements of inheritance, passed down from one generation to the next. Inheritance in sports isn’t talked about enough. The only women’s team sport that is on the cusp of generational inheritance is the U.S. women’s national soccer team. Almost certainly, any player who wears that uniform in the future will find, awaiting them, a rabid fan base, an elevated platform—something like stardom. But the USWNT has, among other advantages, the racial makeup of its talent pool—predominantly white—and the rare double double of the Olympics and World Cup, two stakes-and-story-lines events. (Yes, the WNBA also has the Olympics, but the team usually toils in the shadow of that year’s iteration of the Dream Team, the men.)

On the other hand, most male athletes grow up knowing that if they excel, a kingdom awaits. The best NBA player will always transcend his game, because his sport includes an altar at which we all worship. It also includes inherited story lines, which fuel media coverage, and will always exist regardless of the specific personnel in the league.

“We’re never a talking point,” says Bird. “If we’re covered, it’s a highlight. And there are times when some of those anchors, they know their s---, and you can tell. And there are times they’re just reading copy. But either way, we are never a story-line topic: Should this coach be fired? Should that player be traded? This player is on the max contract, why? We never have talking heads talking about us.”

I spent seven years at ESPN and routinely pitched WNBA topics during morning production meetings. Resistance existed because “the guys don’t know much about the WNBA” and it “wouldn’t make for good TV.” Well, we could have said the same about every NHL pitch, but the assumption was that people would get educated. That was the job. Yet somehow that logic didn’t extend to the WNBA. And once, when we finally tried a segment, it did, in fact, fall flat. Nobody had done their homework. My male colleagues couldn’t name more than one player. The verdict was “See, that didn’t work; the WNBA isn’t compelling.”

The players in the W, as is often the case, identified the problem and worked to introduce a fix—themselves. As the 2020 deadline for a new collective bargaining agreement approached, the players knew that a lot of foundational issues needed reworking, issues going back to the beginning. When the league launched, it essentially just borrowed the wisdom from the NBA. Those first years, the power resided at the league level, for big things like deciding which players would play in which cities (Lisa Leslie to Los Angeles; Cynthia Cooper to Houston, etc.), to the small things like how players should be marketed, how they should look in a photo shoot (“straight”). “In the beginning, the league was trying to have players fit the image they weren’t,” says reigning WNBA Finals MVP Breanna Stewart. “And it was because the league thought that’s what was best for the league. I remember Sue and [Taurasi] telling me: ‘If you don’t feel comfortable doing a photo shoot, don’t do it.’ There are pictures of them wearing things that they wouldn’t wear. Back then, they weren’t able to be the exact person they are. But that’s changed.”

It’s one of many gradual changes that the WNBA has integrated on the fly, while still playing, while still fighting for its future. In many ways, the league is a completely different specimen than when it launched. Like the Ship of Theseus, which asks whether an object remains fundamentally the same if all its parts have been replaced, the WNBA has been in a steady state of renovation, one piece at a time. Many casual fans think they know what the league is, because maybe they checked it out once at the beginning, or maybe a friend of theirs made some snide comment. But it’s nothing like it was. Over the last quarter century, the power has migrated from the league, to the teams and, finally, now, to the players—where it has always belonged.

The CBA signed in 2020 is an agreement with an eye to the future. Some of the more important aspects are obvious. The players fought for changes that allowed for more player movement, which they rightly recognized as the lifeblood of offseason coverage. A player now reaches free agency after five years, not six, and the number of times a team can “core” a player—similar to the NFL’s franchise tag—drops from four to three, and a year later, down to two. Right away, Candace Parker left Los Angeles for Chicago—a splashy move almost impossible under the old agreement. And now we have a new story line: a blossoming rivalry.

But there are additional shades within the agreement that highlight the players’ keen understanding of why people watch sports. Take the new maximum contract of $500,000, more than triple the previous number. They know that only a few players can achieve that, but that wasn’t the point at all. The headline was the point. The point was to break free of the flawed narrative that WNBA players don’t make money. You know what doesn’t sell tickets? The belief that female players make less money than schoolteachers. The NBA, NFL, MLB lifestyle is an aspirational lifestyle. Not just the athleticism, but also the money, the culture, the fashion, the cachet—it all adds up to cultural capital.

Watching sports is communal, even when alone. It’s about being a part of something—often first with your family, growing up, then with your community. You’ll often hear the argument that if women aren’t watching women’s sports, then men shouldn’t be bothered to care, either. But that’s irrational, because women watch sports for mostly the same reasons men do. “There’s a certain cultural value, status and inclusion that you get as a sports fan if you’re a fan of men’s sports,” says Cheryl Cooky, professor of American studies at Purdue and author of No Slam Dunk: Gender, Sport and the Unevenness of Social Change. “Men’s sports transcend sports itself and becomes a part of the larger cultural consciousness. Of course, both women and men want to be a part of that cultural conversation.”

People watch sports because of how it makes them feel. Sometimes that is nostalgic or tense or blissful, but more often the feeling is cool. It’s why courtside seats for the aforementioned Knicks, with only three winning seasons this century and even fewer bona fide stars, still sell for thousands of dollars and why during the games the latest hip-hop blares even though its most expensive seats are filled by 40- and 50-year-olds, because those guys don’t want to hear what’s on their usual Spotify playlists; they want to live inside a moment when they’re ageless and timeless, part of what’s young and relevant.

The inverse of cool is a cause. And too often throughout the years, the pitch for the WNBA has been something like, Supporting it is the right thing to do, for our daughters. Even though the top players stockpile cash overseas alongside their W contracts, and alongside separate apparel and marketing deals, and even though most of the top players have multiple homes and numerous investments, the belief exists that they don’t make lifestyle money. And that perpetuates the idea of the W as a kind of charity, a Title IX offshoot. Maybe that was true during the 2000s, but it’s not anymore. Investors are just beginning to recognize the tremendous long-term value in owning a WNBA franchise.

Look no further than Las Vegas Raiders owner Mark Davis’s acquisition of the Aces in February. Says Lobo: “Every time a WNBA team has gotten a new owner it’s like, ‘Do they have money, or do they have reaaaaaaal money?’ Because on the NBA side, people have real money. You need owners with money-money, owners who say, ‘This is a status thing for me. I’m proud to sit courtside and wear their gear.’ ”

The W has rarely had owners with yacht money. “Mark clearly has a passion for the WNBA and he’s clearly seen that there’s growth potential,” said Engelbert. “His purchase is a great sign for us. Mark wouldn’t be here if he didn’t clearly see growth potential. Investors are now kind of saying, ‘Hmmm, yeah, this is pretty interesting to me.’ ”

When Art Rooney founded the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1933, more than 80% of NFL franchises had failed. The modern-day NBA claims that half of its franchises lose money. This is not to say everyone believes owners when they cry poor, but rather that a specific team’s profit-and-loss sheet has never been used to degrade the athletes themselves. “Historically, owners of men’s teams have had a very different attitude,” says Dave Berri, professor of economics at Southern Utah. “It’s often a vanity project—just to be involved in the game. But suddenly when it’s women’s sports, you have to make a profit; now you’re running a McDonald’s? Now we have to pore over profit-and-loss statements? When did we decide that’s how we evaluate things in sports? The takeaway is that we love investing in men. Wow, do we ever.”

If you’re paying attention to what Davis is doing, he’s investing because he sees potential. That may seem like common sense, but for women’s sports it’s revolutionary. Male athletes are paid based on their potential, then invested in so they reach it, and it sounds very much like that’s what Davis has in mind for the Aces. A new 50,000-square-foot practice facility near the Raiders’, perhaps an arena all their own—all this after a sit-down conversation with the team’s star, Wilson, to get her buy-in. “Players on marquees on the strip, flying first class to All-Star; we set a bar that’s so high,” Wilson says of the Aces. “And we look at other teams and we might not have championships yet, but we are setting another kind of bar.”

“We’re here to push the envelope,” says Loyd. “Our generation, we’re like, F--- it, we’re gonna do it. A little bit of me is saying a league isn’t a league unless there are players. We aren’t asking for a Lambo and a penthouse suite. We aren’t asking for crazy things. But this generation is fearless. That’s how we play and that’s how we feel about the future. And it’s like, get on board.”

Everyone around the game knows that over the last few seasons the ground has shifted beneath them; they just don’t know how to react. So, the question isn’t whether anyone will heed Loyd’s directive, but rather who will be next and how soon. Will it be ESPN, reevaluating its lukewarm commitment to the W and doubling its on-air presence? Or will it be Nike finally accepting culpability—that they’ve been like vampires: marketing the abstract concept of female power, and of sport as equal, while contributing to its inequality? Or perhaps it will be some blue-chip company recognizing it can partner with women—predominantly Black women—and benefit from a quarter-century of the league’s blood, sweat and tears? Whoever moves first will benefit most.

Yeah, Taurasi should have been the Jordan, but maybe, just like the league itself, she was ahead of her time. Maybe the Jordan is about to walk through the doors. And when that player does arrive, all the scales and models that say women’s basketball players get only this much—this much airtime, salary, marketing dollars, investment—will be blown to smithereens. Because those models are already creaking under the weight of their absurdity, because those models were built without vision, meant to offer women a place but not a chance.

Read More of SI’s Daily Cover stories here

More WNBA:

• How a Hoodie Became the WNBA’s Defining Symbol

• Cynthia Cooper Is the League’s Unsung Star

• How the ABL Helped Pave the Way for the WNBA

• Key Players for Each Team