Candace Parker’s Journey From Chicago to Chicago

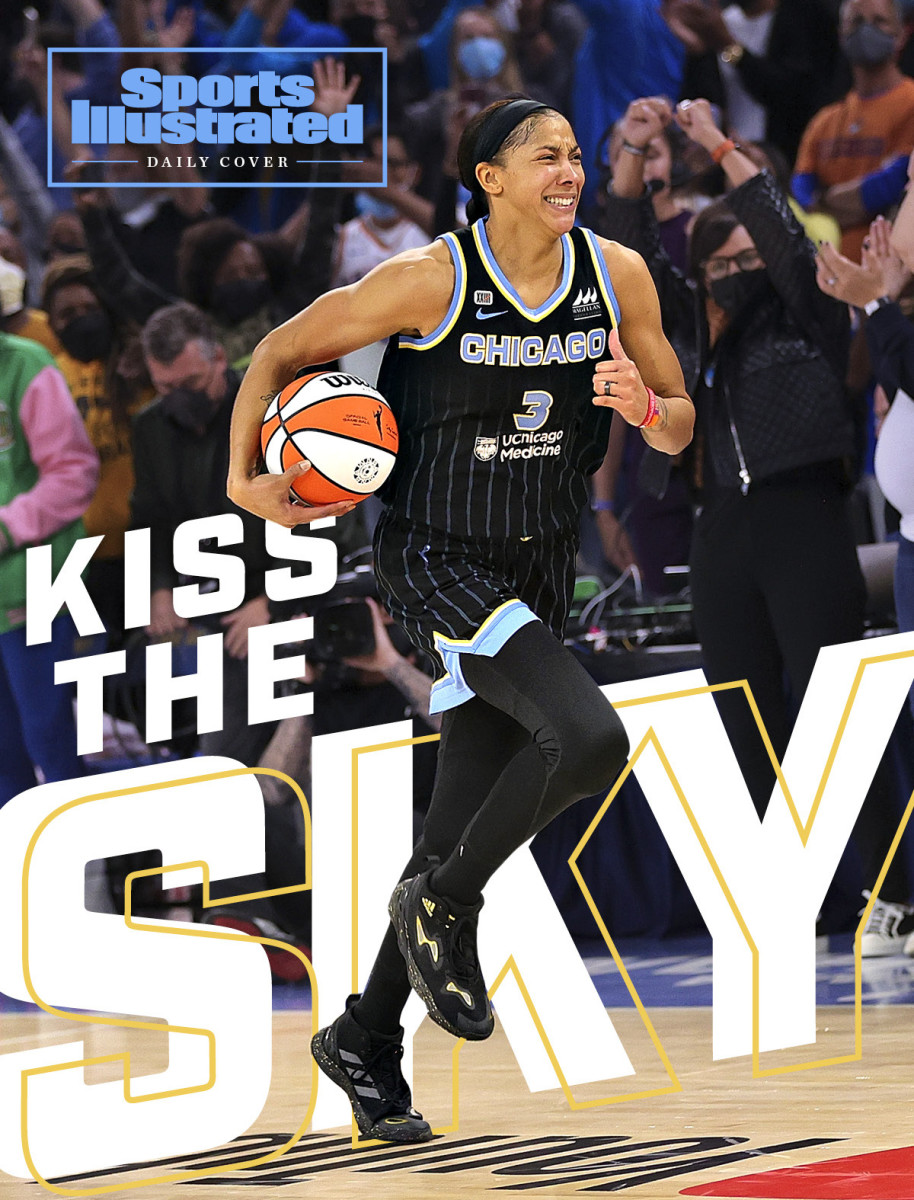

Candace Parker had no work left to do, but because she is Candace Parker, she kept working. She grabbed one last defensive rebound and ran toward her family, a sprint that took a few seconds and all 35 of her years—a journey from child prodigy to veteran leader, and from Chicago to Chicago.

The Sky are WNBA champions, after an 80–74 Game 4 win over the Mercury that Parker and Sky coach James Wade both called “a microcosm of our season.” They meant that the team started slowly—the Sky, who began the season 2–7, trailed Phoenix by 11 early in the fourth quarter Sunday. But the Sky did not just turn it on when it was necessary. They turned inward when it was necessary.

The Sky, the sixth seed, were 16–16 in the regular season and had to win two single-elimination games in the playoffs. Yet by the end they were clearly the league’s best team. In the semifinals they beat the league’s top seed, the Sun, and reigning MVP, Jonquel Jones, in four games. In the Finals, they whipped two first-team All-WNBA players, Brittney Griner and Skylar Diggins-Smith, and the recently declared greatest player in league history, Diana Taurasi.

Parker, a former league MVP, spent much of the season cajoling her teammates to be the best versions of themselves. A few weeks ago, they held a team meeting in which everybody had to name someone for whom they wanted to win. Parker named guard Allie Quigley, a fellow Chicagoland native. Quigley scored a team-high 26 points in the final game, including back-to-back three-pointers in the fourth quarter, but she was not the Finals MVP. Neither was Parker. Neither was Quigley’s wife, Courtney Vandersloot, perhaps the best passer in league history, who finished Game 4 with 10 points, 15 assists, nine rebounds and a gentle scolding from Parker, who thought Vandersloot should have said she needed one rebound for a triple double before Parker grabbed that last one: “I would have tipped it.”

The Finals MVP was speedy guard Kahleah Copper. When the announcement came over the speakers at Wintrust Arena, Parker smiled like she had won the award—which, in a small way, she had.

“I don't think she realizes her impact,” Copper said last week, “far beyond her skill set.”

When the Sky wooed Parker back to her hometown as a free agent last offseason, they tried every Chicago trick except bribing her alderman. They sent popcorn from Garrett’s and pizza from Giordano’s and Lou Malnati’s. Parker had spent her entire WNBA career with the Sparks, but she has never stopped being from Chicago. When her mom picks her up at the airport, she likes to go straight to Portillo’s for her usual: a jumbo chili cheese dog with no onions, large fries, a chocolate-cake shake and a chocolate cake.

Parker chose the Sky, of course, yet she is still a Chicagoan in spirit but not in residency. She spent the season at a rented apartment in suburban Northbrook because she does not own a place in Chicago. She will continue to raise her daughter, Lailaa, in L.A. She did not go back to Chicago to live close to home, and she sure as heck did not do it to watch the snow come in off Lake Michigan. She wanted to fulfill a promise that her talent unwittingly made.

Nearly 20 years ago, as a Naperville Central high school sophomore, Parker dunked in a game, immediately transforming herself from top recruit to national story. The next morning, there were news trucks outside her house.

“I was playing overseas at the time,” says her brother Anthony, a former NBA guard. “That was my little sister. I came back, and we’d walk around, and I was Candace Parker’s brother. It happened that fast.”

Her mother, Sara, told her to ignore the hype: “That’s just other people’s opinions.” The dunk made Candace a celebrity, but the crowds at her high school games saw who she really is: a fundamentally sound two-way player whose brilliance is in the details. She is tied for 10th on the WNBA’s all-time assist list, an incredible achievement for someone who is nominally a power forward. In this series, she sometimes guarded 6' 9" Griner in the post, ran out to hedge screens on the perimeter, then resumed guarding Griner.

Parker wanted to play before the people who watched her as a kid. Like Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot, who told Sara that she used to go to Naperville Central games and now watches her regularly with the Sky.

It’s a lovely story now, with the championship in hand. But the Sky had not gone deep in the playoffs in years. Parker wakes up every morning with an assortment of reasons to stop playing. She has had seven knee surgeries. She needs acupuncture and cupping, and, when Wade gives her a rest during games, she spends the time on the bench getting therapy for the herniated disc in her back. She once dislocated her shoulder during the NCAA tournament, kept playing anyway, led her Tennessee team to the national title and finally needed surgery years later after it popped out and wouldn’t go back in. Her family can tell from the opening few minutes whether her body feels good that night.

Two games into this season, Parker stepped on somebody’s foot at a shootaround. The doctor’s diagnosis was a left ankle sprain, and Parker’s assessment was even more alarming: “I rolled it bad,” she told her mom. Parker once went through a serious workout two weeks after giving birth and returned to the lineup a few weeks later. If she says it’s bad, it’s bad.

The Sky lost their next seven games. Quigley says, “We didn’t know who we were.” They missed Parker’s playmaking and her defense, but they were still benefiting from her example: the daily maintenance on her body, the assurance that she had won a title and that they could win one, too. One player in particular needed to hear it.

This story of a Chicago superstar going home began with a Chicago superstar going home. In 2017, Sky forward Elena Delle Donne wanted to be closer to her family in Delaware, and so Chicago shipped her to the Mystics in a sign-and-trade deal for a package that included center Stefanie Dolson and a young guard entering her second season named Kahleah Copper.

The Copper we saw in this series—a two-way jet with the ability to create highlights on both ends—appeared in flickers for a while. She had the speed, the athleticism and the drive, but she did not have the kind of overwhelming self-confidence that we usually associate with stars. Though she was a McDonald’s All-American in high school, Copper says, “I just don't think I was that good.” At Rutgers, she did not attempt a three-pointer until her junior year and did not make one until she was a senior. She was always determined to play in the WNBA, but her sister Letia Parks says, “I’m not sure if she felt in herself, like, “I’m gonna get there, I’m gonna get there,’ until it finally happened.” When Copper arrived in Chicago, she would commit a turnover and then look over to the scorers’ table to see if somebody was coming in to replace her. She did not become a WNBA starter until 2020, her fifth season.

The Sky coaches believed Copper could reach another level, but she did it because she heard it from her idol. Parks says the only player she can remember Kaleah talking about when she started playing basketball in middle school was Candace Parker. Two years ago, Copper found herself at a gathering at Parker’s L.A. home, and she called her sister like an Elvis fan calling from Graceland: “I’m at her house.” Then she took a nap on Parker’s couch.

Copper says, “I didn't know her, so I just went there and I just went to sleep.” But Parks says: “She was in awe that she was even there. It’s one of those things that you only ever really dream about.”

Copper says when Parker signed with Chicago, “I immediately knew we were championship contenders.” But she low-keyed it with her sister. “I think she didn’t want to be starstruck,” Parks says. Copper was also the only Sky player who did not text Parker to welcome her. (“I didn't have her number!” Copper says. “She’ll never let me live that one down.”)

Parker is going to the Hall of Fame. She did not need to receive a message from Copper. She needed to deliver one to her.

“I never thought of myself as a superstar or whatever, but it’s funny because Candace always used ‘superstar.’ ” Copper says. “She’s like, ‘You’re next. You’re gonna be the next superstar.’ And I’m just like looking at her like, ‘O.K.—whatever that means!’ ”

It means blowing past defenders with one of the quickest first steps in the game and harassing them on the other end. It means truly expecting to dominate for the first time in your life.

“She just took me under her wing and challenged me, and just was like, ‘I see much more for you and what you can do for us and what you can be for yourself,’ ” Copper says. “I could just feel the genuine belief. And she’s not just anybody, you know. It’s Candace Parker.”

Although Parker is a deeply unselfish player, the season was dotted with reminders of what a star she is. During the losing streak, Copper says the Sky missed her ability to take playmaking pressure off Vandersloot. When Copper and Parker stayed in L.A. for an extra day after a game, Parker said, “Stop worrying about it. I’ll get the jet.’ ”

Says Copper: “I’m like ‘Wait, wait, wait, what?’ ” She did not ask questions about the private jet that Parker arranged: “I just got my a-- on the plane.”

On a few occasions in the Finals, Copper embarrassed the great Taurasi by blowing past her. Parker urged her to lead more, too: “I’m not a big talker,” Copper says, but she has come to realize that “sometimes I have to talk more. I just have to.”

One day this summer, WNBA commissioner Cathy Engelbert called Copper, and Copper says, “I was like, ‘Damn, did I not pay a fine?’ I just did a total blank.” She knew the league was announcing All-Stars that day but did not make the connection. She received her first All-Star nod. It was the highlight of her career to that point. It turned out to not even be the highlight of her season.

The Sky’s championship meant so much to so many people that it would be wrong to put them in order. Copper has definitive proof that her biggest fans were right about her. Quigley and Vandersloot now have two days when they picked up rings together: the day they married each other and Sunday. Dolson, who rolled for a crucial lay-in late in the game, won her first title, too.

Wade can use this title to look both backward and forward. He hugged his mentor Dan Hughes afterward, then cried when he talked about him: “Dan was the first person who told me I was going to be a great head coach, and I thought he was crazy as s---.” Now every player he coaches will know they are listening to a championship coach.

Wade arrived in Chicago two years ago and took Quigley and Vandersloot to Max and Benny’s Restaurant in the north suburbs and, according to Vandersloot, “He told us he wasn’t taking the job unless me and Allie were going to be here.” He also promised a championship. He admitted Sunday that he didn’t know how the Sky would win one, but he figured it out. After the Sky’s Game 2 loss, he emphasized the team’s defensive rotations and late-game execution but did not overwork them. These are veteran players. They are better off watching film and resting than going too hard in a playoff practice.

Parker could look around Sunday and marvel at the world she helped create. When the WNBA was formed in the 1990s, Chicago was the center of the basketball universe but didn’t even have a team; Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf did not want his employees working on what seemed like a novelty. Parker was the first high school girl to announce her college choice (Tennessee) on TV. She appears on TNT and wins arguments with men in the Hall of Fame—who could have imagined that?

Now she is a Chicago champion. The Finals games at Wintrust were sold out. Rob Judson, who coached Anthony at Bradley, attended Game 3. Sara sat next to Justin Fields, the Bears’ starting quarterback. Parker said winning reminded her of high school state championships; maybe it was all the coaches and players from her childhood in the stands.

After Game 3, security guards walked Parker out so she could say hi to her mom, who was waiting in a car. Sara asked how Candace was. “I’m good,” she said. “Just tired.” Tired had never stopped Candace Parker before. Less than 48 hours later, she won her second championship and the first WNBA title for her hometown. She had 16 points, 13 rebounds and four steals. Larry Parker likes to watch a replay of every game that day—he was up until 1 a.m. after Game 3—but this time, let’s save him the trouble. Ignore the slow start and missed shots. In the context of Candace Parker’s life, this was the perfect game.

More WNBA Coverage: