How Russia Pushed the WNBA to a Crossroads

Editors’ note, Dec. 8, 2022: Brittney Griner has been freed from Russia in a prisoners’ swap, according to President Joe Biden. The following story, about how women’s basketball players were and are affected by her detainment, was first published in April.

As players report for the WNBA’s 26th season, set to begin May 6, the league is riding unprecedented momentum: It boasts soaring ratings, heightened cultural awareness and a fresh infusion of cash thanks to a $75 million round of fundraising that included the likes of Laurene Powell Jobs, Condoleezza Rice and Nike. And yet, more than a dozen players, talent evaluators and agents who spoke to Sports Illustrated described an equally unprecedented cloud of uncertainty hanging over the women’s professional basketball landscape.

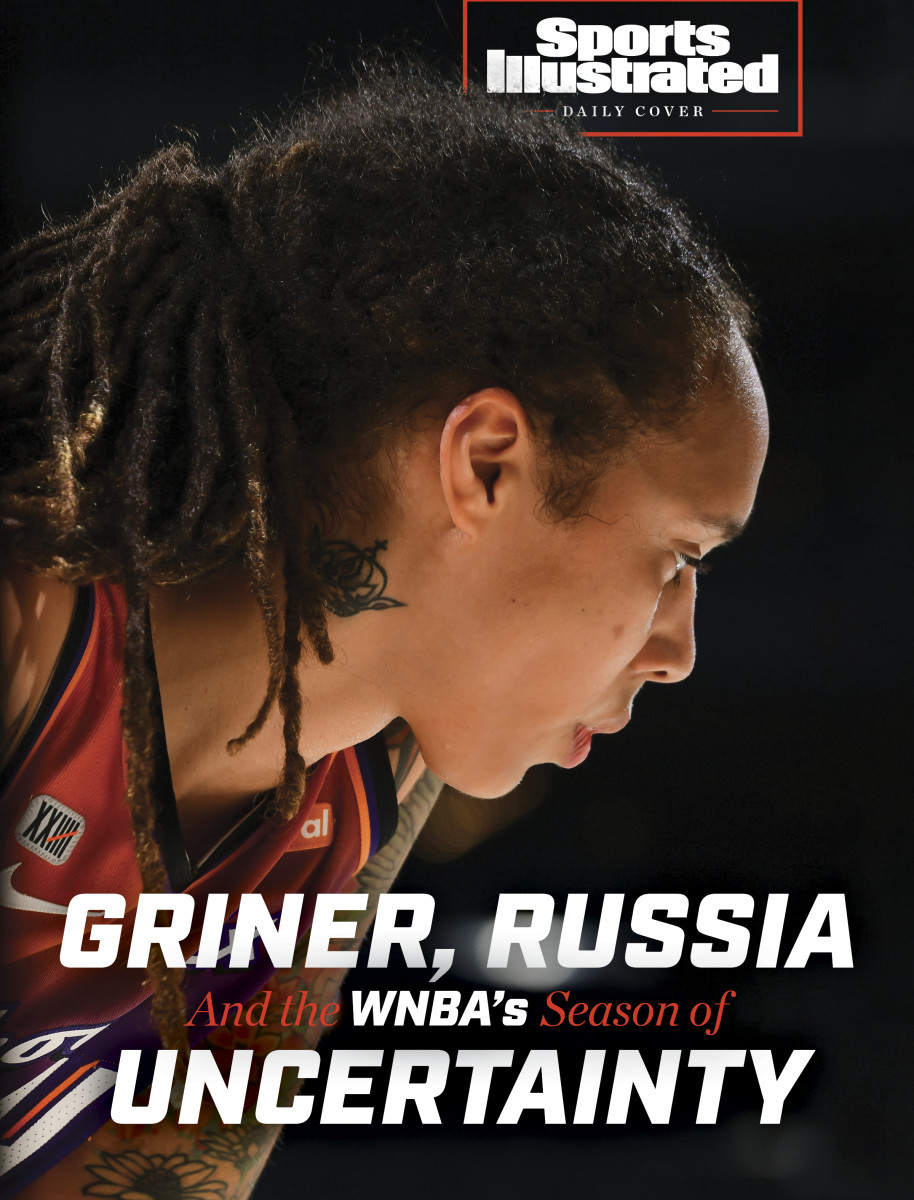

Much of it stems from Russia’s arrest and detainment of Mercury superstar Brittney Griner: Conversations between players now center on how best to help Griner, and whether it is better to publicly speak out or keep silent, as her family has reportedly requested. In the back of many players’ minds is a simple, haunting thought: It could have been me.

That knowledge leads to another major source of uncertainty: Roughly half the WNBA players also played overseas in 2022, supplementing their salaries from the WNBA—which range from a rookie minimum of $60,471 to a supermax of $228,094—with oftentimes much fatter international contracts. Typically, over the first few months of the WNBA season, players and their agents are busy lining up those overseas gigs in Australia, in Turkey, and in, yes, Ukraine and Russia. But the arrest of Griner, detained until at least May 19, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have thrown the sport and its money-making ecosystem into flux. The only thing anyone is sure of, as SI learned in its interviews, is this: Everything is about to change.

The most lucrative overseas contracts to be found anywhere were long given out in Russia, specifically by three teams: Dynamo Kursk, Nadezhda Oremburg and Griner’s team, UMMC Ekaterinburg, where players can earn six or even, in rare instances, seven figures per season. Those squads are no longer options and may not be for some time, if ever again. Meanwhile, China, until recently a prominent option for WNBA players like Phoenix’s Tina Charles, remains closed to overseas players due to its zero-COVID-19 policy.

And so the usual talk between agents and their overseas contacts of team fit and dates has been supplemented with questions like: Is your family out of harm’s way? And, when the ruble plunged in value: Will my clients even get their money?

“It's just an unknown,” Storm star Breanna Stewart said earlier this month at USA Basketball minicamp in Minneapolis. “As far as overseas, obviously, Europe is gonna keep doing what it does. EuroLeague is gonna continue to keep happening. The state of Russia, I'm not sure. And it's just one of those things that you kind of wait and see.”

Amid all this turmoil and global tragedy, the general belief among players, executives and agents alike is that the WNBA, strangely, has an opportunity. The optics of players going to earn their real money overseas (at the expense of staying in the public eye Stateside) have long nettled league executives who, in the most recent collective bargaining agreement, won new strictures on international play. Players, meanwhile, have long been frustrated that the WNBA doesn’t pay them enough to justify staying at home in the offseason. Now, with the Russian and Chinese leagues out of play and the WNBA riding a new financial high, the league has a chance to show players it can be their exclusive basketball home. At her recent predraft press conference commissioner Cathy Engelbert said, “We are creating an economic model where we’re aiming for players to prioritize the WNBA.”

Will she succeed?

Prioritize is the watchword around the WNBA these days. The process bargained as part of the 2020 CBA to restrict overseas play is called prioritization and it sunsets, over time, players’ ability to play an overseas season, then report late, either during training camp or even missing games in the WNBA season itself. This coming offseason, all players who are beyond zero to three years of service will be fined 1% of their annual salary for each day of training camp missed and suspended if not in market by the beginning of the regular season. In 2024, that suspension applies for the start of training camp itself.

And no, teams will not have the discretion to forgive their stars’ penalties. It will be enforced at the league level.

Accordingly, a player like Stewart, who will be a free agent this offseason and in incredibly high demand, can simply elect to sign late this year. But by 2024? It’s going to be a choice for her and every other established veteran in the league. Nobody is quite sure how prioritization is going to play out. “It's gonna be interesting,” Stewart said at the end of her comments in Minneapolis.

“There’s the pro side, which is, hey, everyone’s gonna be on time,” one team executive says, offering the optimistic vision. “And that's fantastic. And we’re gonna have a really good product from day one of the season to show the fans.”

Then there’s the other way things could turn out, the source says, “where you have the disaster of really top players just … not here. And that’s really scary.”

Several players and agents tell SI that they or their clients would not think of playing in Russia until the Griner situation is resolved and, of course, the U.S. sanctions against Russia are ended. But the lure of the Russian payday—the chance to accumulate generational wealth—is so great that if relations ever return to “normal” and the money spigots once again start flowing, they believe that they or their clients would most likely return. The longer Griner is imprisoned, of course, the more that calculation could change.

That gives the WNBA a window of opportunity to convince players they are better off staying home—an outcome, incidentally, that the players would like, as well, though not at the expense of their economic earning power.

Or, as one WNBA agent puts it: “You know, it’s not like people wake up and say, ‘Hey, I want to play in Russia.’”

“You’ve gotta be built different a little bit to go over there,” says the Aces’ A’ja Wilson, who played one season in China (hurting her knee and leaving after just four games) and has not returned overseas. “... You have to understand that you’re there for something that’s bigger than you and you’re providing for your family. Those are the conversations that I hear. And that’s why I credit my teammates for doing it. Because it takes a lot to do that, completely separated from your world. … I've experienced that for maybe a couple of months. And I was just like, this isn’t for me. And it takes a lot to say that, just step away from it. Because you’re missing out on money. You’ve got to find other ways to get that. And that’s sometimes the hardest part.”

Another factor will be the ripple effect of Russian and Chinese leagues falling off the table. Suddenly, the overseas market is without its crown jewels, which moves everyone up a peg, from Turkey to Australia. But between the missing top teams and the resulting more players available, the financial incentives are likely to change dramatically. Top players may not have the same level of financial incentives at the top of the market.

That does not mean other foreign leagues won’t try to jockey for position. One league source tells SI that Australia’s WNBL, whose season doesn’t overlap with the WNBA, believes it can get a bigger star level of player, despite contracts that typically pay less. Another league executive says there are already rumblings of EuroLeague—where the Russian teams have played—considering a change in the calendar to accommodate the WNBA’s stricter policies. Meanwhile, Athletes Unlimited, a Las Vegas–based upstart that ran a five-week season earlier this year and has announced a second one for 2023, will also bid for WNBA players’ services, even if it hasn’t been able to offer the requisite dollar figures yet to attract big stars. As of now, it offers players a base salary of $8,000, with the chance to hit upward of $10,000 in performance bonuses.

“I do think that other leagues are like, O.K., well, we might need to adjust,’” a WNBA source tells SI. “And that's really, to my knowledge, never happened before. The WNBA has always been the league that adjusts, we adjust for everything.”

Lynx forward Aerial Powers says the WNBA’s compensation just needs to get close to what players can earn by supplementing with overseas play to get them to stay—a feeling that, in SI’s conversations, represented something of a consensus.

“So I don’t know if you can get to that,” she says. “But if you can, I’m sure girls will not go overseas, because no one wants that toll on their bodies, to be away from their families.” When pressed on whether she thought the league could get to a number that would work for most players, Powers laughs and says, “You’d have to ask Cathy!”

She was referring to Engelbert, commissioner of the WNBA. And Engelbert does have a number of tools in her toolkit she’s already begun using. The league, as part of the new CBA, can sign marketing agreements with individual players that can more than double what is otherwise the max salary of just under $230,000 to more than $500,000. In other words, the commissioner is able to direct additional salary from the league to players in exchange for performing requested tasks to amplify the WNBA’s message—anything from live public appearances to media requests. The Liberty’s Betnijah Laney, Lynx’ Napheesa Collier and Aces’ Dearica Hamby have reportedly already benefited. And a number of league sources tell SI the recent investment of $75 million from selling equity in the league can expand the total number of agreements, even as the salary cap and max salaries remain unaffected by the new capital.

There is also a looming financial windfall coming, one that could fundamentally change the economics of the entire league: a new media rights deal. The current agreement with ESPN dates back to the middle of the last decade and pays a pittance compared to virtually any parallel contract—just $25 million a year. One league source tells SI the WNBA will shoot for $100 million per year for the new deal, which would begin in 2024. By comparison, Major League Soccer, a similar league in season size, television ratings and even age, already receives $90 million per year for the expiring rights deal it has. And that is considered well below market value.

“By 2024, sponsorship dollars will continue to increase as women’s basketball athletes grow more and more into household names and cultural icons,” texts WNBA agent Allison Galer of Disrupt the Game, who represents players like the Sparks’ Chiney Ogwumike and Amanda Zahui B. “Television viewership, media coverage and social media conversation will be perfectly poised for 2024 to be a monumental year with the Olympics and the national WNBA television agreement set to be renegotiated.”

A massive influx of new capital should trigger the provision in the CBA that allows for players to receive half of basketball related income when certain revenue targets are met. Agents are already doing back-of-the-napkin math on it—one told SI they are envisioning maximum salaries around $1 million. “That would end overseas,” the agent says.

An improved media rights deal would also likely lead to higher profiles for WNBA players, leading to more off the court possibilities, says WNBA agent Erin Kane of Excel Sports, who represents Elena Delle Donne among others. “Once the earning potential for players in the U.S. exceeds what they can earn overseas, the choice is simple.”

Kelsey Plum, an Aces guard who has played overseas in the past, is paying close attention to all of it. Like her USA Basketball teammates, she’s watching the Griner situation, frustrated that she cannot do more or know more.

“I think there’s a lot of questions that people have,” Plum says. “And to be frank, I don’t think they've been answered.”

At the same time, second income streams are never far from any WNBA players’ mind. The Lynx’ Powers has her own side-hustle in esports, where her Twitch stream has become one of the platform’s most popular. She said she can’t stop thinking about Griner—her meals, her daily life—but she is also hardwired to think about money. She says she hopes that Griner is taking notes so that one day she can write a bestselling book.

“It was sad because it’s like, you know, this could have been you,” Powers says. “This could be any one of your teammates.”

Read more of SI’s Daily Cover stories here:

• Behind the Spectacle of Colin Kaepernick's Comeback Tour

• The Complicated Legacy of Jackie Robinson Day

• Sportswashing Is Everywhere, but It’s Not New