Honoring Major Taylor, America's first black world champion in any sport

Looking back from the vantage point of today’s sports-crazed society, it seems inconceivable that the first African American world champion from the United States would be relegated to obscurity. Yet that’s the lot of Marshall (Major) Taylor, the star-crossed cyclist who, more than a century ago, was this country’s most recognizable and wealthiest sports figure.

“I wish for him a much bigger legacy, because he deserves it,” says Todd Balf, author of Major: A Black Athlete, a White Era, and the Fight to be the World's Fastest Human Being. “His story is still relatively untold. It hasn’t really penetrated our social conscience the way it should.

“Those athletes that do discover Taylor are blown away by him. Not only was he a champion, he was this super-human athlete with this amazing body,” says Balf. “He’s had a tremendous influence over the people he’s reached. But it still seems like an accident to come across his story. It shouldn’t be. It should be a part of American history.”

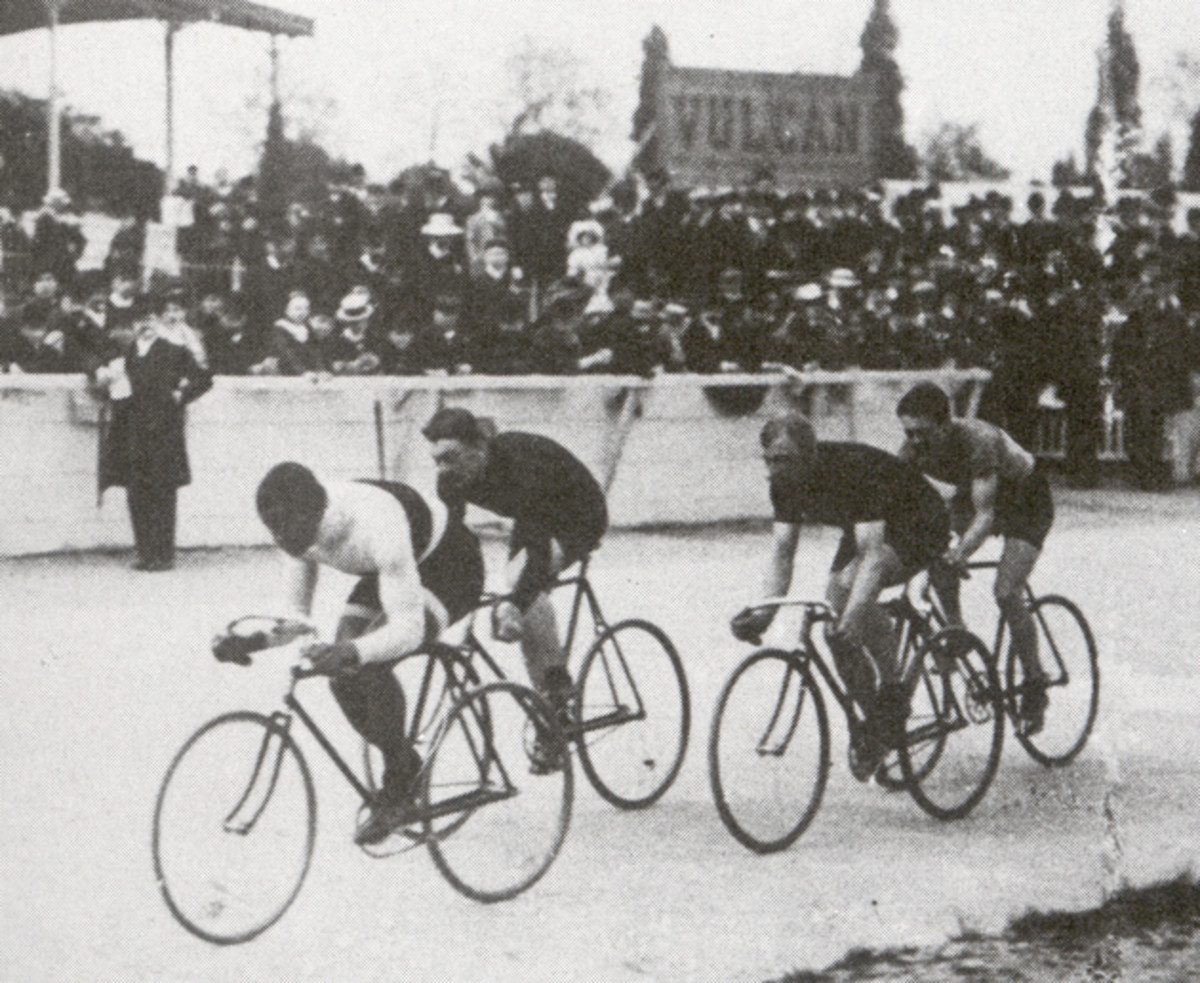

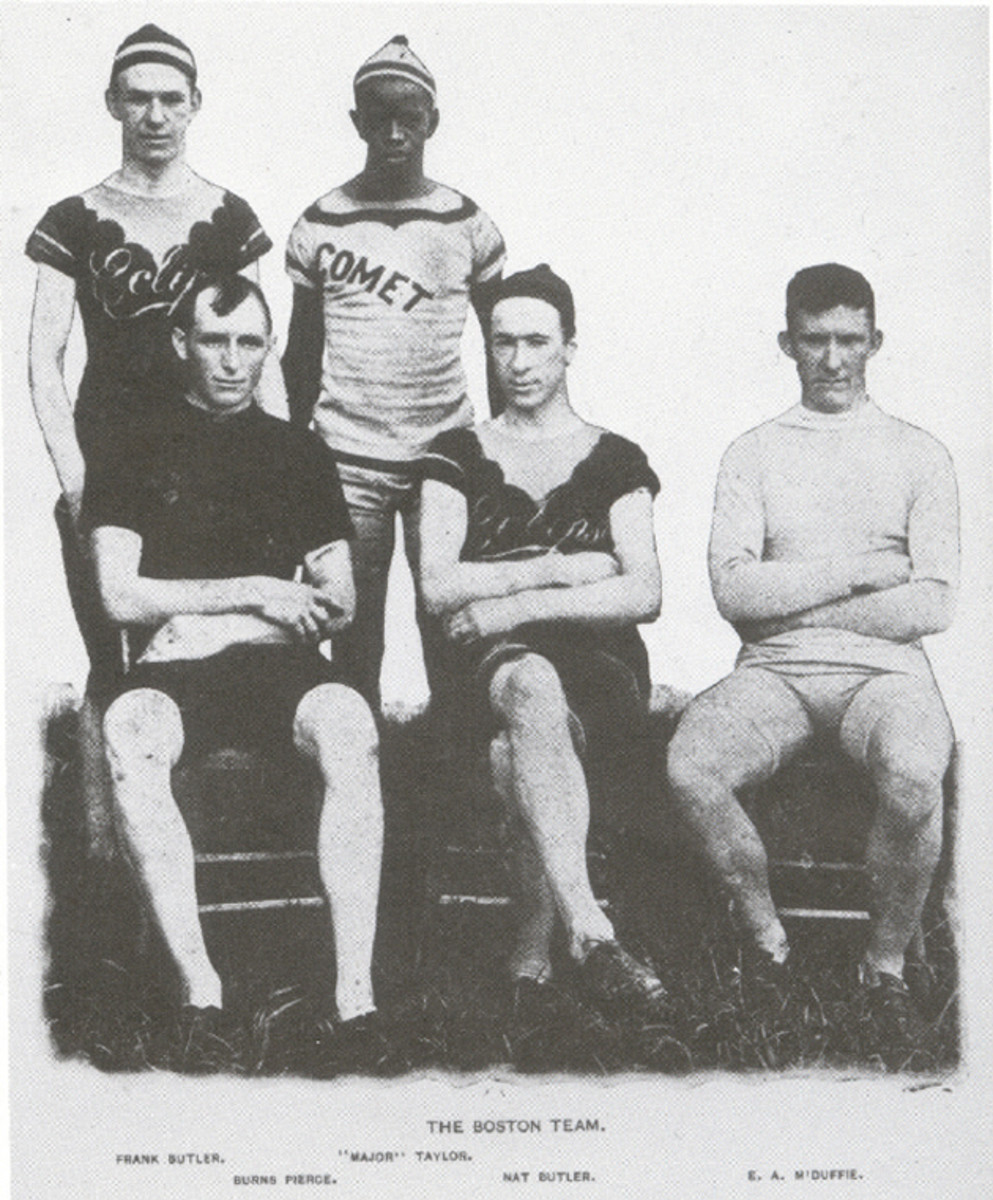

Taylor was three months shy of his 21st birthday when he lined up against three white men—Boston brothers Tom and Nat Butler and France’s Courbe d’Outrelon—for the final of the 1-mile world sprint championships on Aug. 10, 1899, before a crowd of more than 12,000 at Queen’s Park velodrome in Montreal.

Unleashing the scathing finishing sprint that made him the most feared and most popular bicycle racer of his era, Taylor blew past the Butlers and d’Outrelon to win by inches.

“He has the most perfect sprinter’s build you’ve ever seen. It just screamed ‘explosiveness,’” says Balf. “That’s certainly what he was known for. When you think about that era, there was a real fascination with speed.”

Love the NFL's high-tech tricks? Early innovators put the ball in play

Taylor’s breakthrough world championship came nearly a decade before Jack Johnson, who admired Taylor, became the first black American to win boxing's heavyweight title. It came 37 years before Jesse Owens buried the myth of Aryan supremacy at the Olympic Games in Berlin, and 48 years before Jackie Robinson shattered baseball's color barrier. Taylor was only the second North American of color, after Canadian bantamweight boxer George Dixon, to win a world championship.

“Major was the first African American international sports superstar,” says Lynne Tolman of the Major Taylor Association. “Taylor took his impact onto the world stage,” she says. “He really cemented the impact of his world championship when he went overseas.”

That Taylor even made it onto the track in Montreal is remarkable, says Andrew Ritchie, author of Major Taylor: The Extraordinary Career of a Champion Bicycle Racer. Ritchie’s detailed account chronicles Taylor’s career, from his birth to descendants of slaves in 1878 to the pinnacle of his sport in two short decades, to his death 32 years later.

The United States of the late 1800s was a sharply divided nation, with the raw, open wounds of the Civil War still fresh, says Ritchie. Though Taylor lived in the “free state” of Indiana, he couldn’t escape discrimination. He wasn’t even allowed to join the YMCA. He learned about white society through his relationship with a wealthy Indianapolis family that hired his father.

Later, Taylor worked for several bicycle shops, earning the nickname Major by performing stunts in a soldier’s outfit. He started racing, and winning, much to the dismay of his white competitors. Eventually, he teamed with cycling enthusiast Louis (Birdie) Munger, who became a father figure, employer and manager.

When Taylor was prevented from racing against whites in Indiana, he joined Munger in Worcester, Mass., where the racial climate was more tolerant and velodromes dotted the landscape. Still, prejudice hounded Taylor. The League of American Wheelmen (LAW) was split on racial issues, and at a 1894 meeting in Kentucky it passed a “white only” rule (despite the objections of the Massachusetts members).

With Munger’s support, Taylor secured a professional racing license from the LAW’s New York board. At 17, Taylor was a lightning rod. He stood out, not only because of the deep brown color of his skin, but also because of his undeniable talent and noble bearing.

“What grabbed me about Major Taylor was his aura of dignity, the way he endured,” says Tolman. “He faced so many closed doors and so much open hostility with remarkable dignity.”

Taylor and his entourage also faced near-constant threats of violence off the track. Yet Taylor, a deeply religious man, maintained decorum without being submissive.

Into the Wild: Fighting the trail, the cold and 430 miles of solitude

“He was sharp enough to know that he couldn’t have done it any other way, because he would have been dead,” says Ritchie. “It worked for him because his personality predisposed him toward the ‘turn-the-other-cheek’ attitude.”

Dignified and disciplined, Taylor was fierce on the track. Errant elbows and collisions were common. Taylor often found himself blocked by scheming riders jamming his path to the finish. That tactic forced him to race from the front, an unenviable position for a sprinter hoping to conserve energy by riding in another racer’s draft.

After winning his world championship in 1899, Taylor also set the paced 1-mile world record in Chicago, averaging 45.5 miles per hour. He was, says Ritchie, “the most hated, the most admired, the most controversial, the most talked about, quite simply the most famous athlete in America.”

“You had to be impressed with the sheer speed, which was a huge deal in those days,” says Tolman. “He titled his autobiography The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World. But really, he was the fastest human on the planet.”

Immediately after his victory lap in Montreal, the “fastest human on the planet” thought about his home.

“It was the first time I had triumphed on foreign soil, and I was thrilled as I heard the band strike up The Star-Spangled Banner,” wrote Taylor in his memoirs. “My national anthem took on a new meaning for me from that moment. I never felt so proud to be an American before, and indeed, I felt even more American at that moment than I ever felt in America.”

Taylor flourished “on foreign soil,” finding fame and fortune racing in Europe and Australia, where the social atmosphere, if not utopian, was more enlightened. A devout Baptist, he wouldn’t participate in world championships held on Sundays. But he was dominant the other six days of the week.

“He had personality,” says Balf. “He knew how to charm people, how to work a crowd. When he was traveling through Europe, and especially when he was living in Paris, they loved him. They adored him, because he was a cultured human being with a full life. He wasn’t just an athlete. He was much more.”

The peak of Taylor’s career overseas came in 1902-04. At a time when baseball’s best players were paid $2,500 annually, Taylor was earning well in excess of $10,000.

“His color, which stood in his way in America, was the foundation of his appeal and attraction all over the world, and his speed and style continued to thrill spectators in every country he visited,” wrote Ritchie. “During these two years, he was probably the world’s most sought-after athlete and almost certainly the most traveled sportsman in the world. He was, without a doubt, the world’s most illustrious black athlete.”

With that newfound celebrity, Taylor also found his voice.

“He was an interesting athlete at a time when there were two approaches to take in the face of racism. And that hasn’t changed that much,” saya Balf. “You could either work quietly against it, or you were militant, and rose against it in a much more strident way.

Driven by success: Why getting to the next level is all in your head

“Major was of two minds. He really was torn. Early in his career, he was very tolerant. He understood that he had to suffer all sorts of racial abuse and indignation, and he just coped with it. But as he gained stature, and especially as he became known in other countries, he saw that it didn’t have to be that way. He became more outspoken and wasn’t as inclined to tolerate the things he tolerated as a young man.”

In 1910, at 32, after a decade of non-stop travel and unrivaled accomplishment, Taylor retired. The sport, and his country, allowed Taylor to fade away. His disappearance from the public eye in the United States was dramatic and swift. The same fate befell the bicycle.

"A whole generation of men went off to World War I. Then the automobile arrived,” says Tolman. “That's all you have to know about cycling in this country.”

Or, as Ritchie wrote, “a dead sport does not remember its own past.” Johnson and Robinson owe their legacy in part to the continuing popularity of boxing and baseball. Taylor didn’t have the same platform. While many cyclists today are aware of Taylor—according to Tolman, there are 32 clubs nationwide linked to the Major Taylor Association, and at least another 10 that bear his name—the general sports audience in this country has no knowledge of the man.

“What it really comes down to, unfortunately, is that cycling is really historically under-appreciated” in the United States, says Balf. “That period, the late-1800s and early 1900s, when cycling was the biggest game in town, doesn’t really resonate.”

“Cycling was a mainstream sport then,” says Balf. “Madison Square Garden was filled with fans, and every major city had a velodrome, and the grounds had 20,000 and 30,000 people. Huge crowds. The heyday was brief, but for that short period of time, he was the best thing going.”

Taylor died on June 21, 1932, in the charity ward of a Chicago hospital, and was buried in an unmarked grave. He was 53.

“This topic is perfectly appropriate for Black History Month, but Taylor's story needs to be told broadly,” says Balf. “That’s the way I always thought about this story. It wasn’t a sports story. It wasn’t a black history story. It was an American story. A really, really perfect American story.”

In 1989, 90 years after his landmark triumph in Montreal, Taylor was enshrined the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame in Davis, Calif. Speaking at the dedication of the Major Taylor monument in Worcester, on May 21, 2008, three-time Olympic medalist Edwin Moses said that Taylor’s name should be mentioned in the same breath as those of other trailblazers, including Johnson, Owens, Robinson, Ali, Arthur Ashe, Tommie Smith, and Hank Aaron.

“Today, Marshall (Major) Taylor will take his rightful spot at the top of this distinguished list,” said Moses.

Taylor, recalling his 1899 world championship, wrote: “I shall never forget the thunderous applause that greeted me as I rode my victorious lap of honor around the track with a huge bouquet of roses.”

It would be a shame if Taylor's country forgot him.

To learn more about Major Taylor, visit the Major Taylor Association.