A History of Football in 100 Objects

Five years ago The MMQB—with a nod to the British Museum and the Smithsonian—presented NFL 95, telling the story of the league through 95 artifacts. For the 100th season, we’ve expanded and updated the project. Why is the NFL’s game ball called “The Duke”? Who devised the slingshot goalpost? Whatever happened to that Ford Bronco? From the Hupmobile to Shad Khan’s yacht, Tom Dempsey’s boot to Deion’s bandana, Don Hutson’s cape to Tom Brady’s draft card to the notorious corset that introduced the phrase “wardrobe malfunction” into the American lexicon, here’s a century of the NFL as told through things.

Capsules by the MMQB staff and Damichael Cole, Mitchell Gladstone, Torrey Hart, Bobby Sullivan, Ethan Thomas and Morgan Turner.

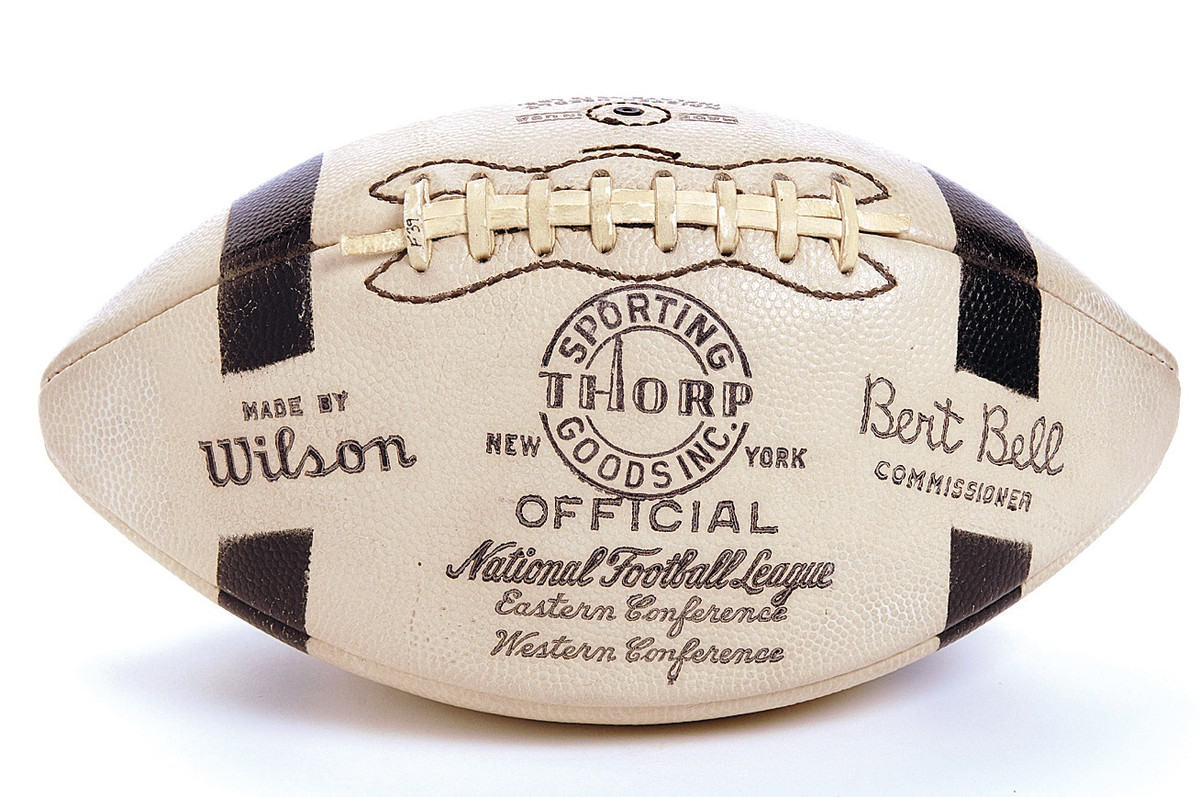

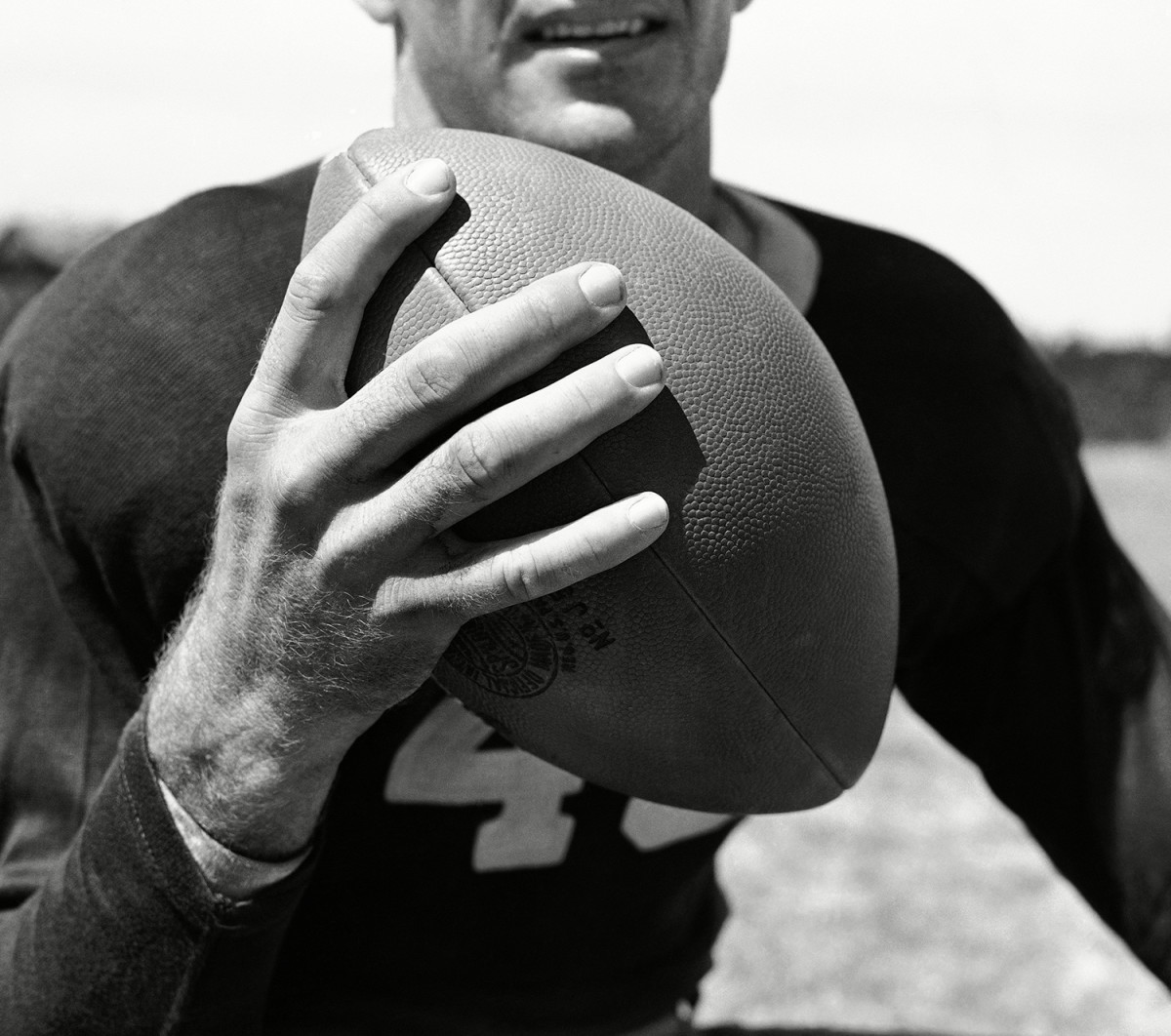

“The Duke” Football

It’s hard to think of anything more iconic in football than the “pigskin” itself (which, of course, is really cowskin.) The story behind its nickname: Future Giants owner Wellington Mara was named after the Duke of Wellington by his father, Giants founder Tim Mara. In the 1920s, when Wellington was a ball boy, the players dubbed him “The Duke.” While at the helm of the team, Tim Mara inked the NFL’s deal with game ball supplier Wilson. Following that monumental agreement, Chicago Bears owner and coach George Halas suggested the ball take on a moniker in Wellington’s honor, and it officially did so in 1941. That ball remained standard until the merging of the National Football League and American Football League in 1970.

Wellington Mara fought in World World II, then returned and was named team vice president of the Giants under his brother, Jack. After Jack’s death in 1965, Wellington took over as Giants president. Through the years he earned a reputation among players, fans and colleagues for level-headed leadership and dedication to the Giants and the league.

After his death in 2005, the NFL returned “The Duke” name to the league’s Wilson balls in his honor, while Mara’s legacy lives on through his son, Giants co-owner John Mara. In a time when the league is adopting new rules and has been rocked by controversy, “The Duke” is an homage to simpler times. You wouldn’t really notice if it changed—the label is merely ornamental, after all—but knowing it’s there makes it all the better.

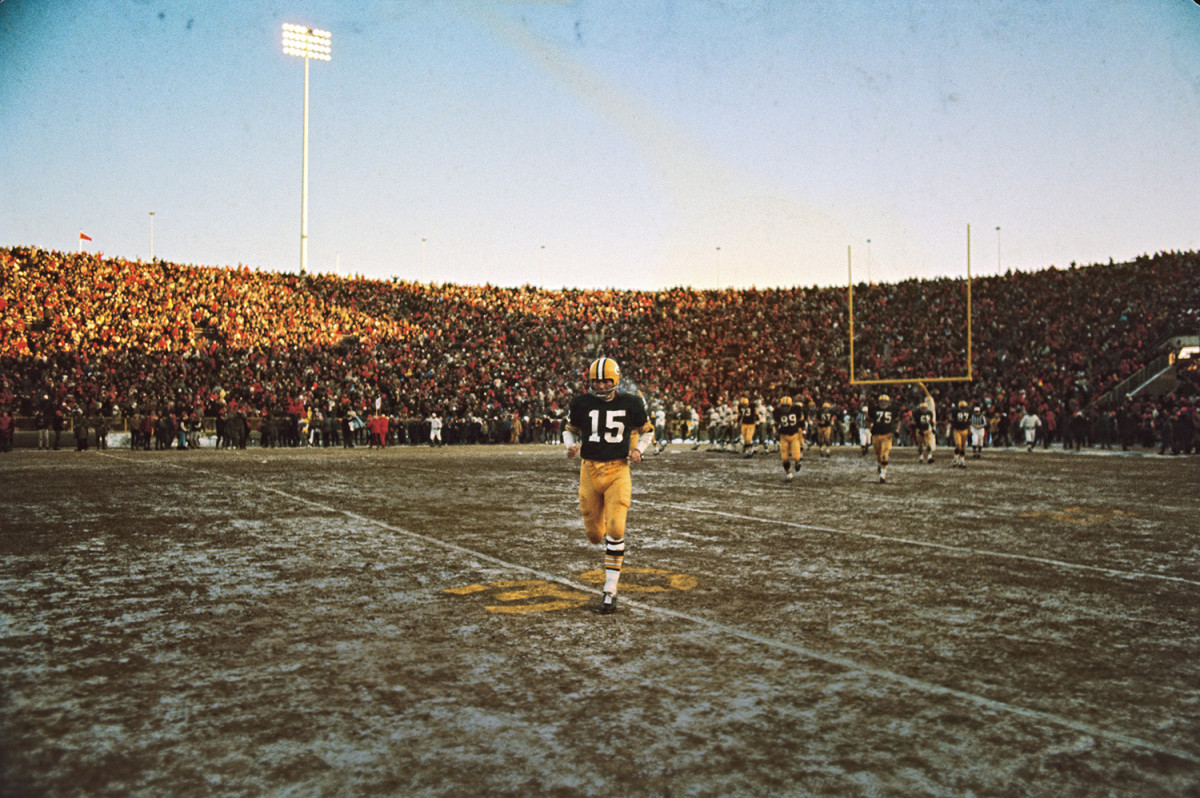

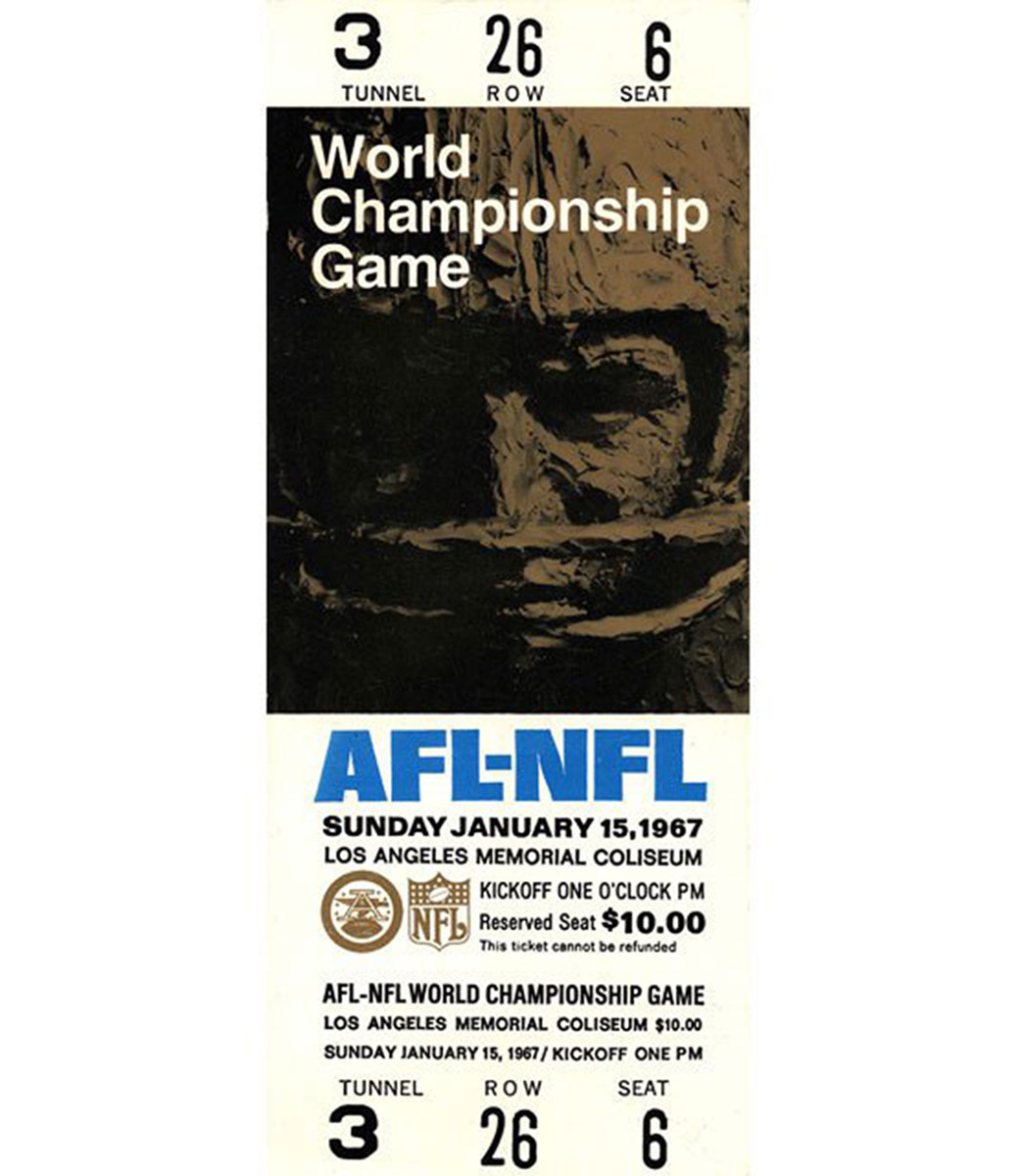

The Frozen Tundra of Lambeau Field

When the Packers and Cowboys awoke on Dec. 31, 1967, the day of the NFL Championship Game, they were greeted by temperatures of minus-15 degrees with the wind chill around minus-48. Lambeau Field, which had fine footing during the walkthrough the previous day, had become a sheet of ice because the turf-heating system had malfunctioned. When the tarps were taken off the field, the moisture on top flash-froze.

Temps warmed to a balmy minus-13 and minus-38 wind chill by kickoff. The conditions would negate one of Dallas’s biggest assets, its team speed. The game went back and forth, and with Dallas leading 17-14 with 4:50 left in the fourth quarter, the Packers had the ball at the 32-yard line. Bart Starr drove the Pack to the 1-yard line with 16 seconds remaining and no timeouts left. Starr and right guard Jerry Kramer thought they could get enough traction for a quarterback sneak. “Run it, and let’s get the hell out of here!” was Vince Lombardi’s reply. Kramer and center Ken Bowman doubled Cowboys defensive tackle Jethro Pugh to allow Starr to cross the goal line for an eventual 20-17 victory.

The game became famous as “the Ice Bowl,” but it generated another memorable phrase when NFL Films’ Steve Sabol, in his script for the highlight movie, described the Lambeau turf as the “frozen tundra.” A legend was born, one that the current groundskeepers don’t really appreciate. Lambeau now has an advanced system of tubes circulating anti-freeze to keep the surface pliant and playable amid the snow and ice of a Wisconsin winter.

The Slingshot Goalpost

Today the forked goalpost is one of the most widely recognized icons of American football. Two metal rods, standing 30 feet above the end zone, have made or broken entire seasons (just as the 2018 Bears). But the iconic goalpost has not always looked the way it now does. It’s the product of an evolving NFL.

When the league was founded in 1920, H-shaped wooden uprights stood on the goal line. The posts shifted between the front and rear of the end zone over the years as league officials attempted to either decrease or increase kicking attempts—in 1933 field goals were too few and far between, so the posts moved to the goal line; by the early ’70s, attempts had surged to the point that in 1974 the league pushed the posts to the back of the end zone in hopes of persuading more teams to prolong drives rather than go for an easy three. They’ve stood at the end line ever since, and it’s impossible to imagine a change.

But what about the shape? The forked or “slingshot” goalpost can be attributed to hobbyist, inventor and retired newspaper distributer Joel Rottman. The story goes that Rottman was having lunch with Montreal Alouettes coach Jim Trimble when he suggested the now-traditional shape after staring at the prongs of his fork. Rottman’s proposition was not only more aesthetically pleasing, but also safer, as it featured one less standard for players to crash into. The unique “gooseneck” design also allowed the post to sit farther back from the goal line, thus interfering less with play. Rottman built an aluminum prototype, which first appeared at the World’s Fair in Montreal; the display earned him a meeting with NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle.

The first forked goalpost was used in the University of Miami’s defeat of Indiana in the Orange Bowl on Oct. 21, 1966. By NFL opening day in 1967, all 16 teams were equipped with yellow slingshot uprights made by Triman (Trimble-Rottman) Tele-goal Co. The shape has since stood for decades in the end zone without issue—except for an occasional problematic post-touchdown dunk—and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

A Tailgating Grill

Ribs and burnt ends in Kansas City, kielbasa in Pittsburgh, beer-can chicken in Cleveland, beer brats in Green Bay, fish tacos in San Diego, beef on weck in Buffalo, char-grilled gulf oysters in New Orleans, smoked brisket in Houston. If this list doesn’t make your mouth water, it should at least conjure images of one of the NFL’s finest time-tested rituals: tailgating.

And where would fans be without the ultimate tool of backyard-to-stadium convenience, the grill? Enter a stadium parking lot a few hours before kickoff, and you are likely greeted with a waft of charcoal-heavy smoke. Thousands of fans congregate around parked cars, tents and grills in extreme heat, bitter cold, harsh winds, rain, sleet, snow and everything in between. It’s not a way to kill time before kickoff, but rather a football tradition epitomizing the camaraderie of a fan base. Tailgating represents the devotion not only to a team, but also to the traditions those teams have become synonymous with. Faces are painted, fight songs are recited, beverages are consumed, footballs are tossed and the aura of optimism is contagious. These few hours represent football fandom at its purest, and thanks to the grill, it’s delicious.

Stickum

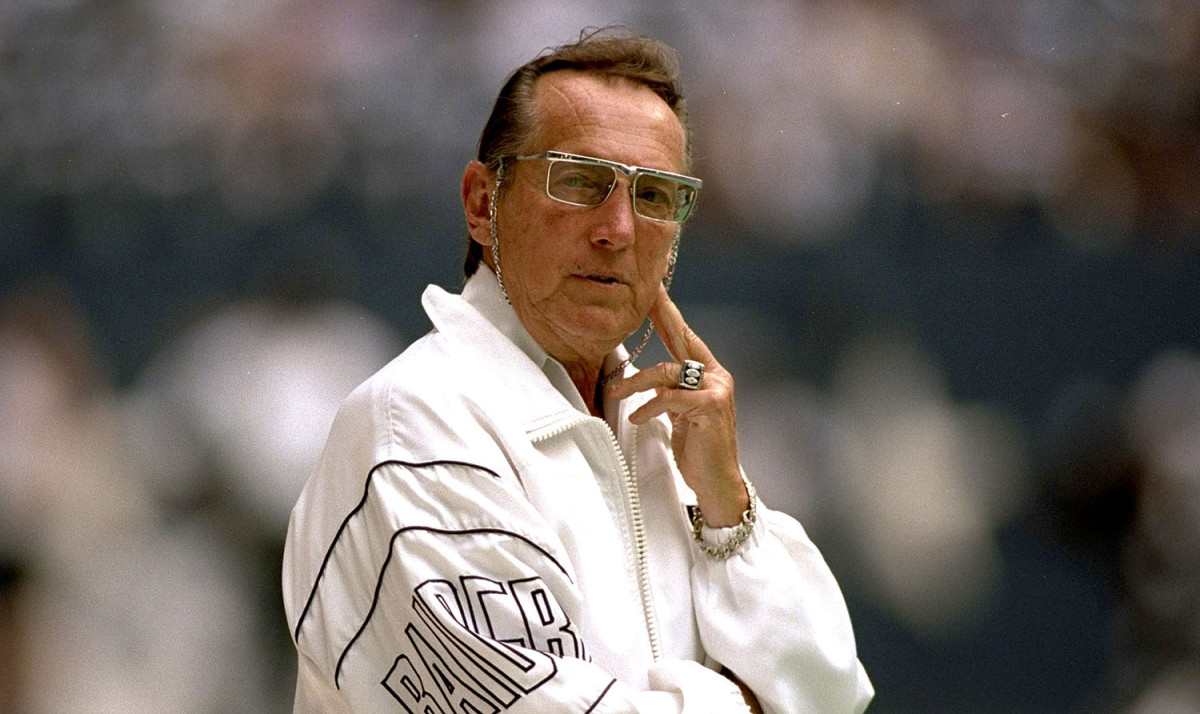

Al Davis was famous for his catchphrase Just win, baby, though some Raiders of the ’70s and ’80s might have taken the owner’s words a bit too literally.

That’s one way to explain why some players smeared themselves with this dark yellow substance before games. Stickum was said to enhance the potential for sure-handed receptions—Oakland Hall of Fame receiver Fred Biletnikoff dabbed the substance on his socks so he could easily reach down for a shmear—or for members of the secondary to elongate the bump in bump-and-run coverage. Though numerous players on plenty of teams lathered up, Stickum is is probably most associated with Raiders defensive back Lester Hayes, who won the 1980 NFL Defensive Player of the Year award with 13 interceptions, then added five more en route to Super Bowl XV. Hayes smeared a half a jar (about nine ounces) on his body each game, the honey-like goo dripped from his forearms, hands and uniform. Competitive advantage, baby.

The NFL banned Stickum and similar adhesives in 1981. In his final six seasons, Hayes never tallied more than four interceptions. Of playing with Stickum, he told the Houston Chronicle in 2004: “I could catch a football behind my back on one knee. It was tremendous stuff.”

Stickum hasn’t been seen since, though the NFL opened an investigation into the Chargers in 2012 after an on-field official thought a towel on San Diego’s sideline might have a sticky substance on it. The NFL found no wrongdoing but fined the team $20,000 for not immediately complying with the official. Consider that being caught in a sticky situation.

Vince Lombardi’s Chalkboard

Vince Lombardi’s domain was Lambeau Field, but his mastery of football was evident on another expanse of green: the chalkboard. That’s where Lombardi drew up the plays that established the Packers’ dynasty of the 1960s.

Plays like the power sweep, the perfect vehicle to illustrate Green Bay’s dominance—and to characterize the coach that made the Packers great. “There is nothing spectacular about it,” Lombardi once said of the sweep that came to bear his name. “It’s my number one play because it requires all eleven men to play as one to make it succeed, and that’s what ‘team’ means.” Every player’s assignment was crucial, but it highlighted the execution of the three interior offensive linemen, the center and both guards, who normally toiled in anonymity. The center, first Jim Ringo and later Ken Bowman, had to execute a difficult cutoff block, against either a tackle or linebacker. That allowed both guards, Jerry Kramer and Fuzzy Thurston, time to pull outside the playside tackle. The off guard had the toughest duty, since he had the farthest to run. “I know it’s a difficult maneuver,” Lombardi once said. “But [the off guard] has to get there. I don’t give a damn whether he enjoys getting there or not.” Then the patience and reading of the blocks by halfback Paul Hornung and fullback Jim Taylor finished off the play.

“You think there’s anything special about this sweep?” Lombardi once asked a writer. “Well, there isn’t. It’s as basic a play as there can be in football. We simply do it over and over and over. … There can never be enough emphasis on repetition. I want my players to be able to run this sweep in their sleep. If we call the sweep twenty times, I’ll expect it to work twenty times ... not eighteen, not nineteen. We do it often enough in practice so that no excuse can exist for screwing it up.”

The Terrible Towel

“Your idea was pure genius,” Steelers president Dan Rooney once told team broadcaster Myron Cope. “But you were too stupid to know what you were doing.”

WTAE was looking for a gimmick. It was December 1975, and in two weeks the defending Super Bowl champion Pittsburgh Steelers would host the Baltimore Colts for a playoff game. The team’s flagship radio station was looking for something to both energize fans and draw the attention of sponsors. Cope, the team’s radio broadcaster, was asked to join a brainstorming session. As Cope recalled in a 1979 essay for Sports Illustrated:

“What we need here,” I said, “is something that’s lightweight and portable and already is owned by just about every fan.”

“How about towels?” [VP of sales Larry] Garrett said.

“A towel?” It had possibilities. “We could call it the Terrible Towel,” I said. “Yes. And I can go on radio and television proclaiming, The Terrible Towel is poised to strike!”

“Gold and black towels, the colors of the Steelers,” someone piped.

“No,” I said. “Black won’t provide color. We’ll tell ’em to bring gold or yellow towels.”

The concept didn’t sit well with players. (Linebacker Andy Russell: “What’s this crap about a towel? We’re not a gimmick team.”) But it was a hit with fans. Cope approximated that 30,000 towels were in attendance when Pittsburgh beat the Colts. The Steelers went on to win a second straight Super Bowl, making Cope’s gimmick a part of the team’s lore.

Before he passed away in 2008, Cope ensured that the Terrible Towel would have an impact beyond the gridiron. His son, Danny, was born severely autistic and required 24-hour care. The Copes sent him to the Allegheny Valley School, where he developed further than Myron thought possible. In 1996, Cope thanked the school by giving it the trademark rights to the Terrible Towel, along with the millions of dollars in royalties that come with it.

The Challenge Flag

Since its inception in 1999, the coaches’ challenge has contributed to countless game-changing moments in the NFL. With the mere drop of a hanky, NFL coaches have the power to force officials to reconsider their calls—not only once, but twice or even three times per half. The results of those challenges can break hearts, or mend them.

In replay review’s first go-round in the league, from 1986 to ’91, there were no coaches’ challenges. Reviews were initiated by an official in the booth, or occasionally by field officials who wanted a second look at a play. When replay returned to the league in ’99, coaches were given two challenges per half (except inside two minutes, when officials would take over), and would lose a timeout if a ruling was upheld. Until 2004, coaches would call for a review via a pager. That gave way to the simpler—and much more demonstrative—red challenge flag. Over the years, as technology advanced and the system was tweaked, the rate of successful challenges has climbed fairly steadily, from 29% in 1999 to 49% in 2019.

The suite of challengeable plays has evolved over the years, and some calls (scoring plays, change of possession) now are automatically reviewed, taking the pressure off the shoulders of coaches. On the other hand, they’re sometimes left itching to throw a flag when they can’t; witness Sean Payton’s impotent fury over the pass interference non-call in the January 2019 NFC title game. It’s cold comfort for Payton that, beginning in the 2019 season, he and his coaching brethren can now toss the flag to challenge pass interference.

The 12th Man Flag

It has been unfurled below the Statue of Liberty and raised above the Space Needle. President Obama posed for photos while holding it up. In the months surrounding Seattle’s Super Bowl XLVIII win, the 12th Man Flag experienced a tour-de-force of sightseeing. But for fans of the Seahawks, the electric-blue nylon piece of fabric with a white No. 12 printed in the center is as familiar as any player on the Seattle roster.

The flag—hoisted before kickoff for each game at CenturyLink Field—represents community, devotion and passion for a fan base that prides itself in having the best, and loudest, home-field advantage in the NFL.

Whether Seattle’s is the best, and whether the Seahawks even have dibs on the term “12th Man,” is up for debate. (Just ask Texas A & M, which sued the Seahawks to protect that trademark in 2006; the two parties settled.) Not in question, however, is CenturyLink’s volume, which, depending on whom you ask, reaches either righteous pandemonium or insufferable loudness. In a night game against the Saints in 2013, Seattle’s fan base regained the Guinness World Record for crowd noise with a 137.6-decibel reading (Kansas City fans at Arrowhead Stadium have been in a tug-of-war with Seattle for this distinction). Another Pacific Northwest legend was born in a 2011 playoff game when fans cheered so hard during Marshawn Lynch’s 67-yard Beast Mode touchdown run that they generated recordable seismic activity. From the field to space, from Lady Liberty to the White House, Seahawks fans and their beloved flag set new standards for fan engagement—and lung capacity.

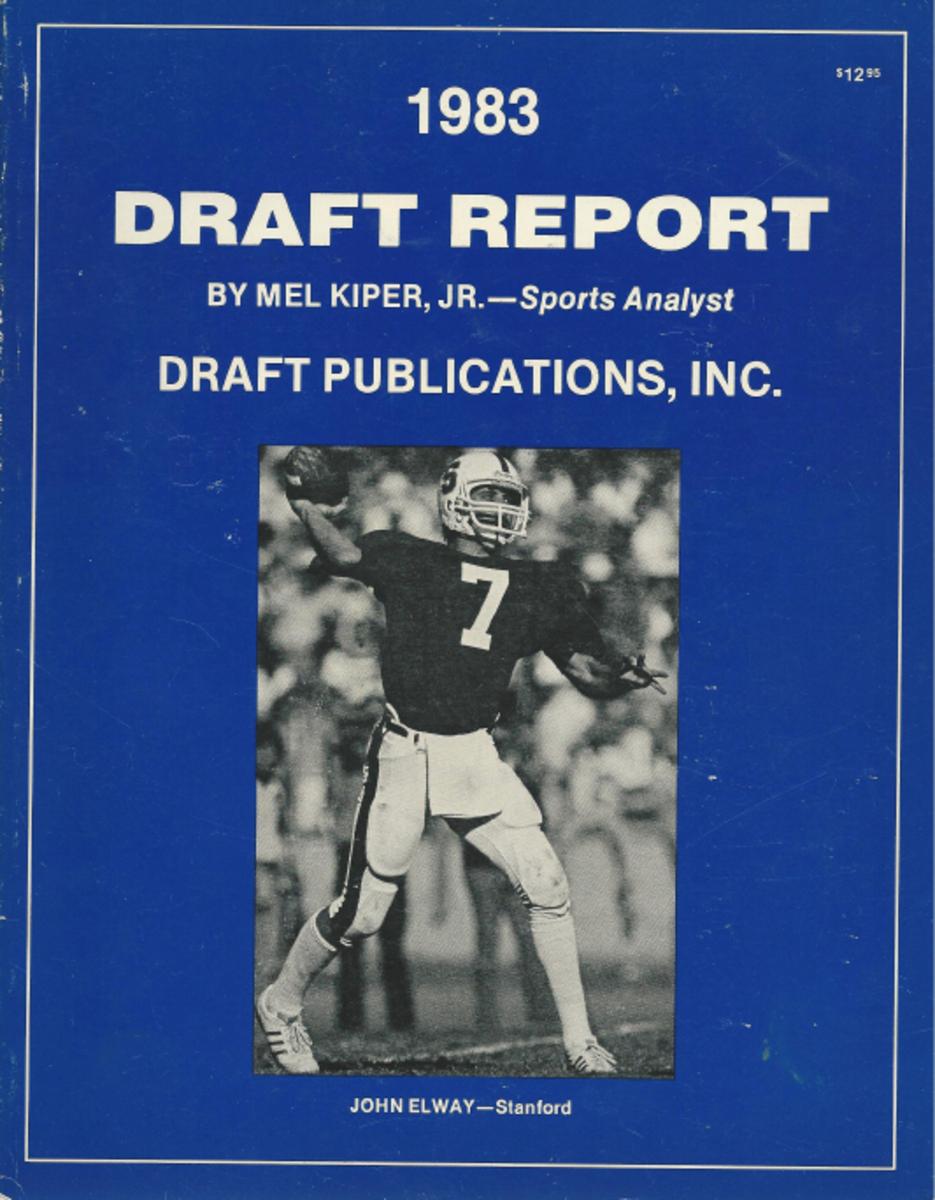

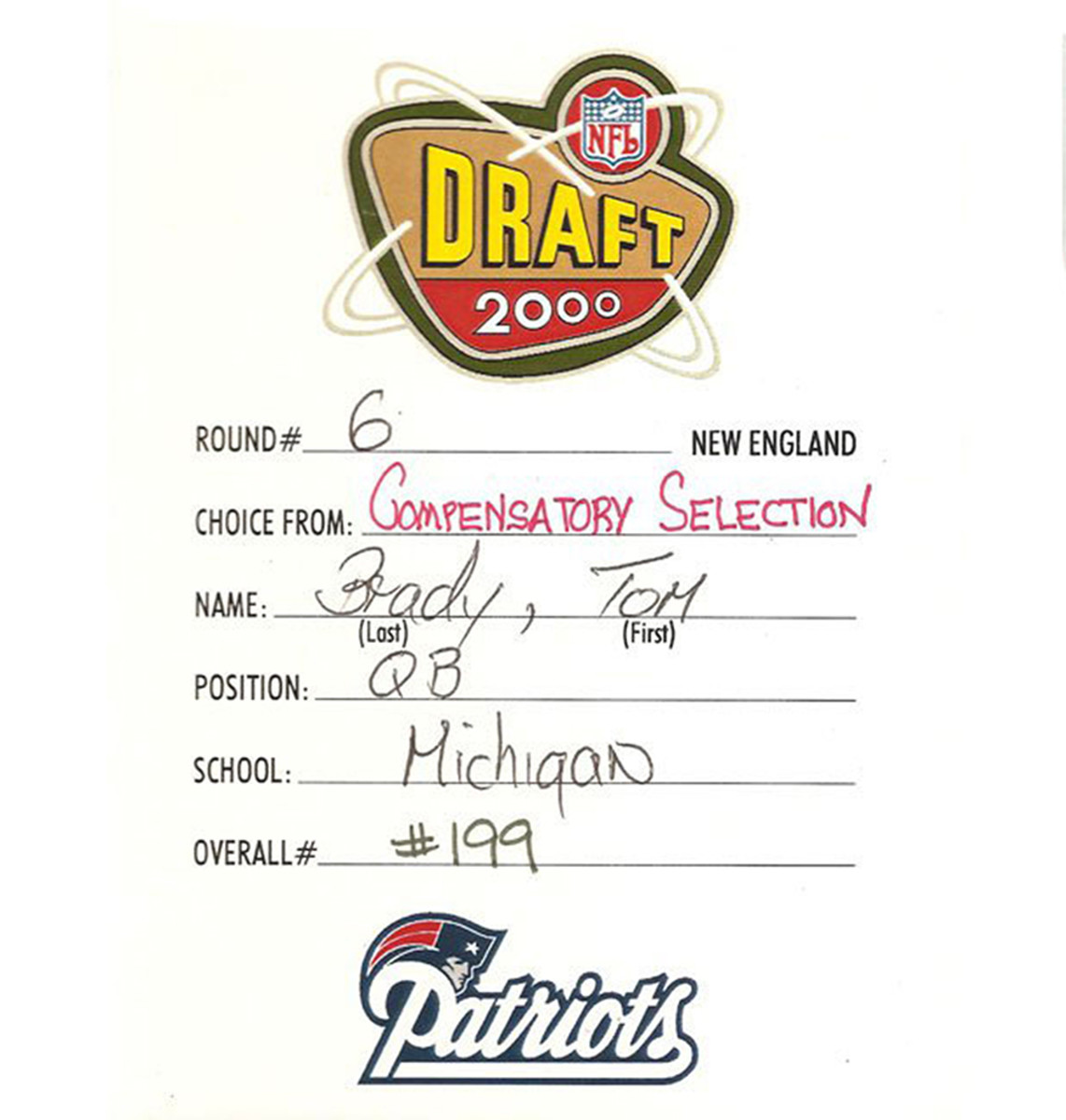

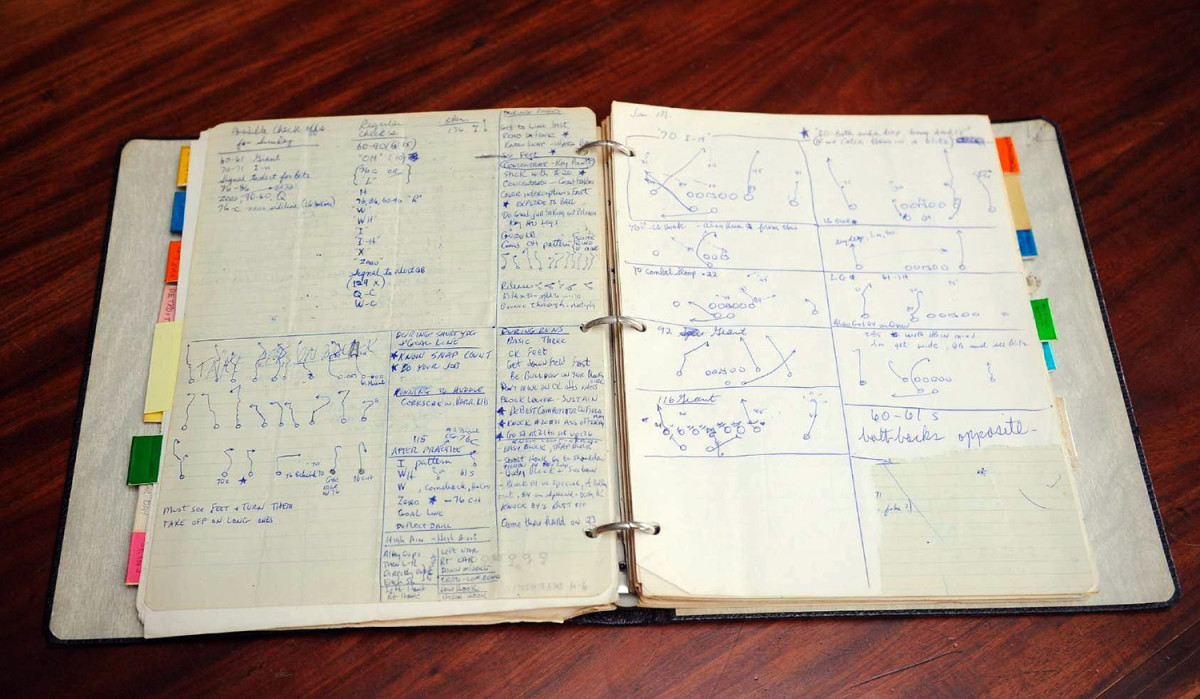

Mel Kiper’s Draft Book

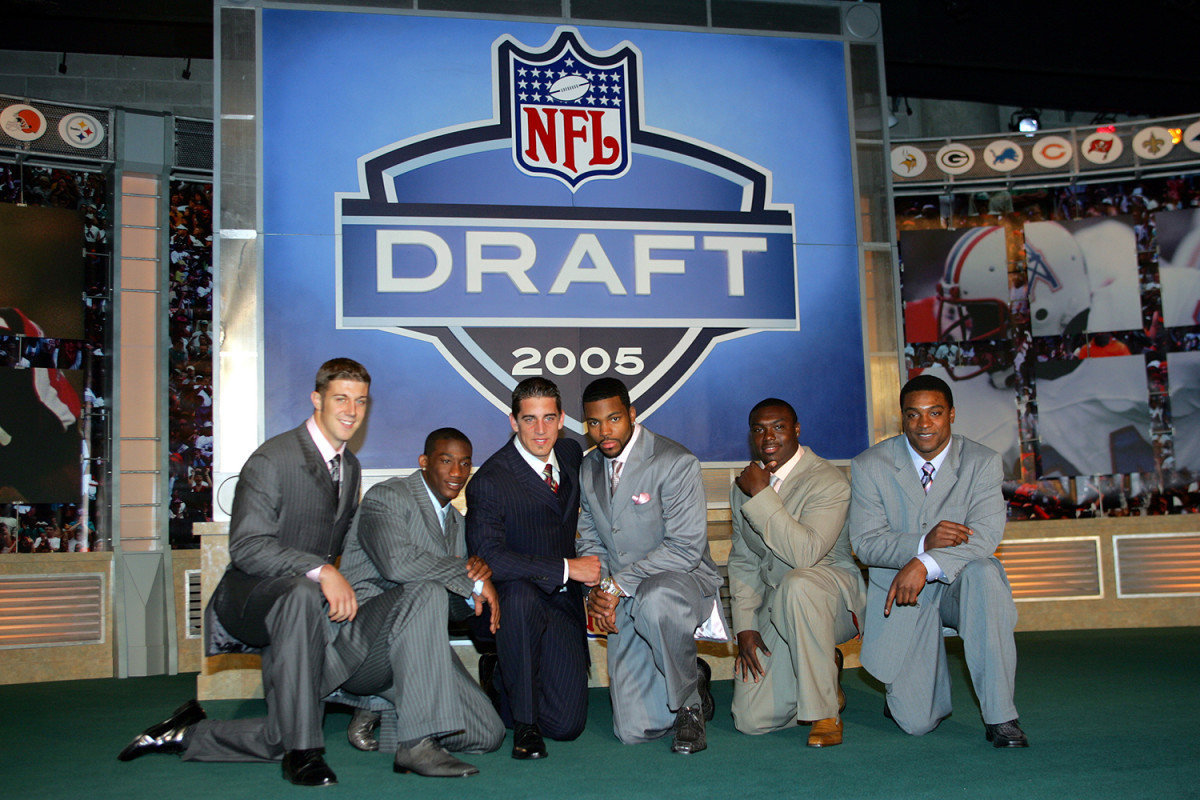

How did this happen? And why hasn’t it happened for baseball, ice hockey or basketball? Everyone watches the NFL draft. In television ratings, it blasts playoff games in every other major North American sport out of the water. With the help of Kiper and dozens of draft gurus who were spawned in his image, ESPN and the NFL turned a quiet hotel ballroom tradition begun in 1936 into the true kickoff of the season; the league even pushed back the draft a month to May to hype the hypiest NFL event other than Super Bowl even more.

Here’s how this happened: A skinny, draft-obsessed kid from Baltimore began charting the NFL’s annual talent parade at age 12 and wrote his first comprehensive draft preview in 1979 as a high school senior. He sent that guide to every team in the league, seeking feedback, and soon he had developed contacts throughout the NFL among personnel people who were impressed with the kid’s dedication, and his knowledge. Operating out of his parents’ basement, Kiper created a market basically out of nothing, selling his draft guide to subscribers and working the phones—“I’d talk to anyone who called me, two minutes to two hours,” he told SI in ’92—to build a network and a reputation. The outsider became an insider in 1983 when Colts GM Ernie Accorsi hired him as a personal assistant. Accorsi would leave the team after the John Elway episode that year, but Kiper had arrived. He made his first appearance on ESPN in 1984 and became a fixture on the network’s draft-day coverage. He also produced his Blue Book every year, until 2014.

No matter. An army of draftniks with their own websites arrived in his wake, all mulling over the same information and issuing their own mock drafts and predictions. The draft has become a landmark on the spring sports calendar. Some say it’s a non-event: No one knows whether a guy will be a Hall of Famer or a bust until he hits the field, and Kiper has had his share of misses over the years. But good on Mel for making his dream come true and helping create an entirely new industry. Not too many people can say that.

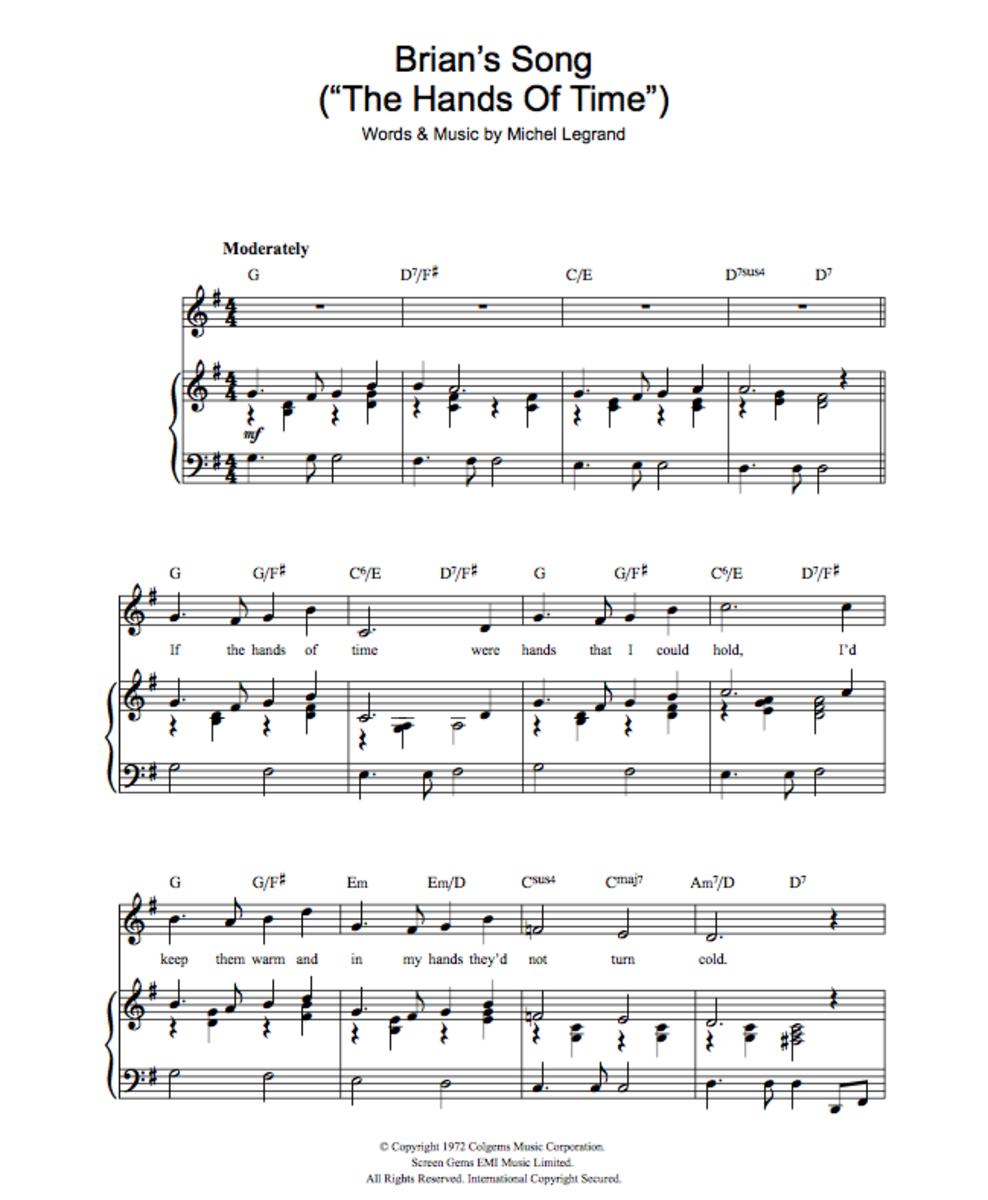

Sheet Music from “Brian’s Song”

As legend goes, sometime after Bears running back Brian Piccolo was diagnosed with embryonic cell carcinoma, he told his wife: “You can’t cry. It’s a league rule.”

In the early ’70s, that sentiment seemed to stretch from the NFL to its fan base. Then Piccolo’s story changed everything. A 90-minute ABC-TV movie on the Piccolo’s fellow Bears back Gale Sayers, a bond that only strengthened as Piccolo’s cancer progressed, tugged America’s heartstrings so hard that it’s nearly impossible to find a fan who can talk about the 1971 film without misting up. Brian’s Song was the movie that taught grown men it’s OK to cry.

What was it about the film that generated such strong emotion? Perhaps it was the nuanced performances of James Caan and Billy Dee Williams. Perhaps it’s just the tale of two men—one white, one black, with seemingly little in common besides football—who form a strong friendship, organically, that endures through tragedy. Piccolo died in 1970 at age 26, but the movie, as its tagline suggests, is “a true story about love.”

Or, perhaps, the sobs stem from the X-factor that ties it all together: music. Composer Michel Legrand (The Thomas Crown Affair, Summer of ’42) was a master of sweeping instrumentals that amplify a movie’s sentiment, and in Brian’s Song nothing tugged the heartstrings more irresistably than its theme, “The Hands of Time.” Legrand’s score builds with the story’s arc, the theme presented in countless variations, and by the time Sayers delivers his climactic, heart-wrenching speech—“I love Brian Piccolo, and I’d like all of you to love him too. ... Please ask God to love him”—the accompanying theme hits its most wistful note. Even the hardest-bitten viewer has been reduced to a blubbering heap. In a good way.

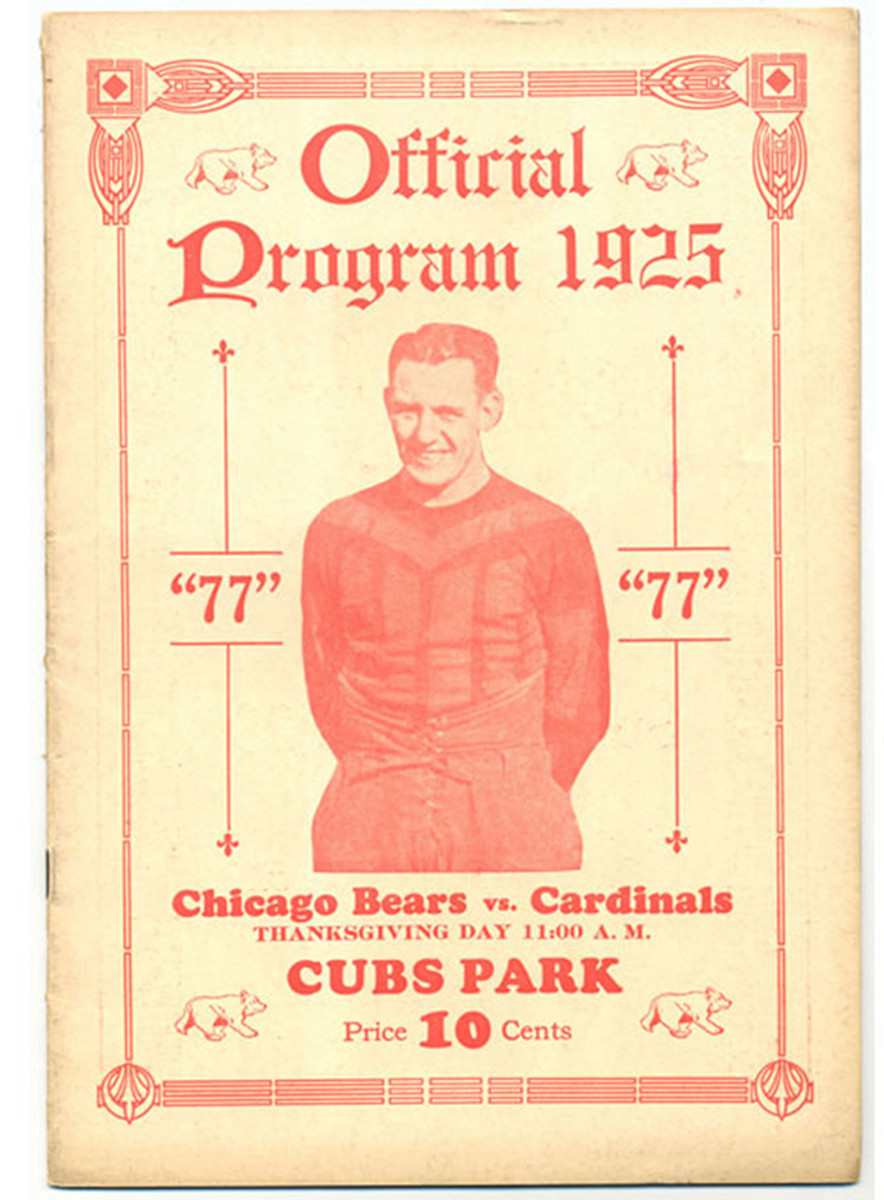

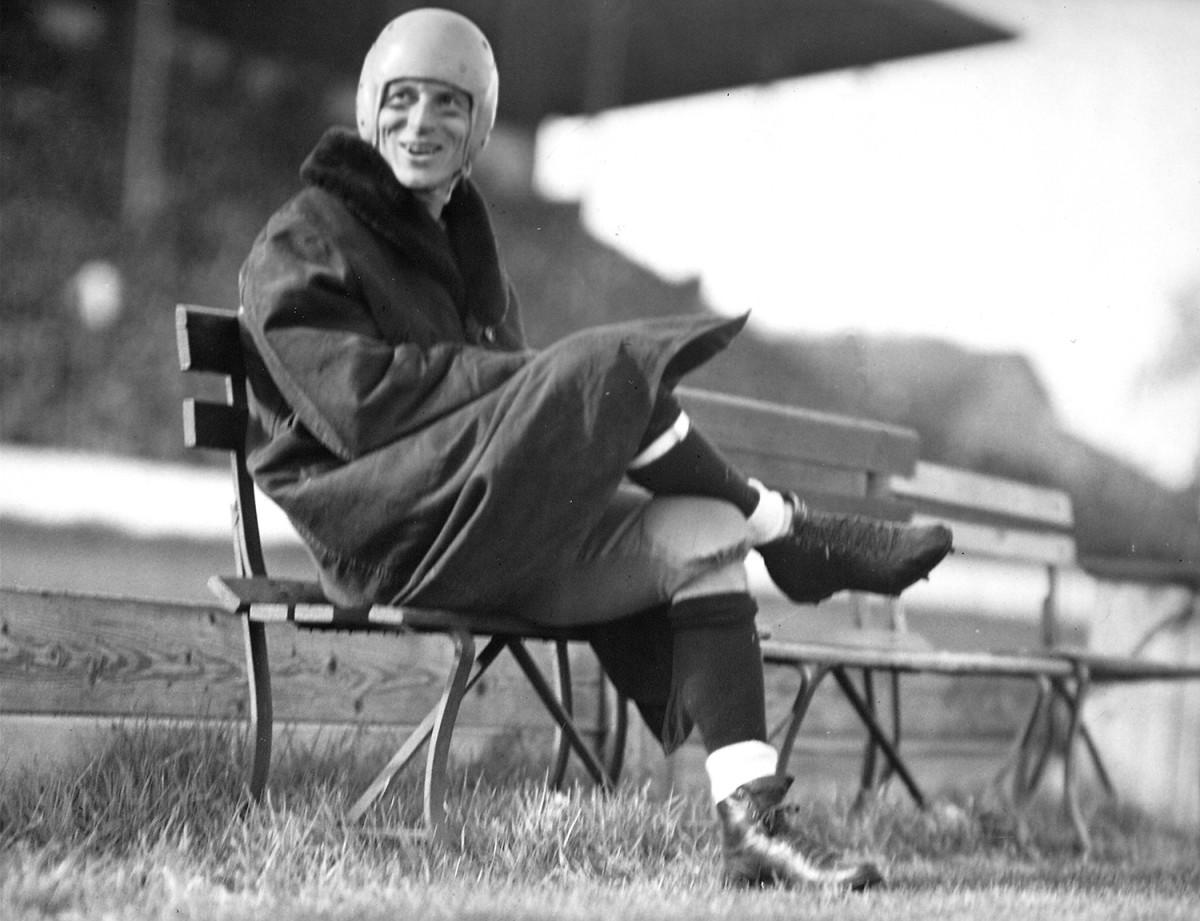

Program From Red Grange’s Barnstorming Tour

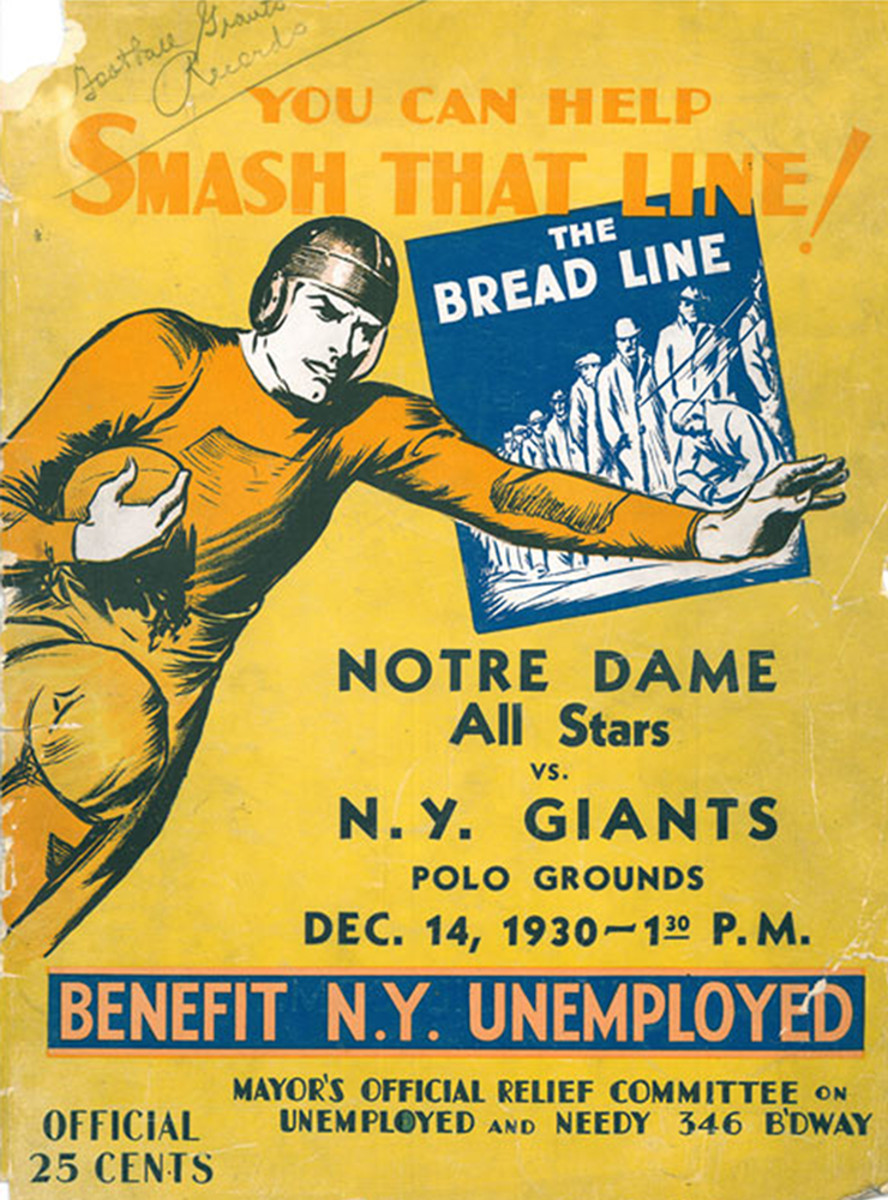

Before 1925, professional football was struggling to gain an audience. More than 20 franchises had folded in the previous four years, and attendance ranged from a few hundred on a good day to mere dozens of spectators on a slow one. That all changed when Harold “Red” Grange, who was called the Galloping Ghost by fawning reporters, became the first player to drop out of school (the University of Illinois) and become a professional football player.

Days later, Grange joined the Chicago Bears and embarked on a 19-game, 66-day tour during the winter of 1925-26. The cross-country tour was organized by C.C. Pyle, considered the first football agent, who signed Grange to a multiyear contract. In his first eight games as a pro, Grange played before an estimated 200,000 fans, including some 70,000 at the Polo Grounds against the Giants, which helped to rescue New York owner Tim Mara from $45,000 in debt. Yankees baseball legend Babe Ruth was among those in attendance in New York that day, as were more than 100 sportswriters. Professional football had finally entered the consciousness of the country, and it had Grange to thank for it.

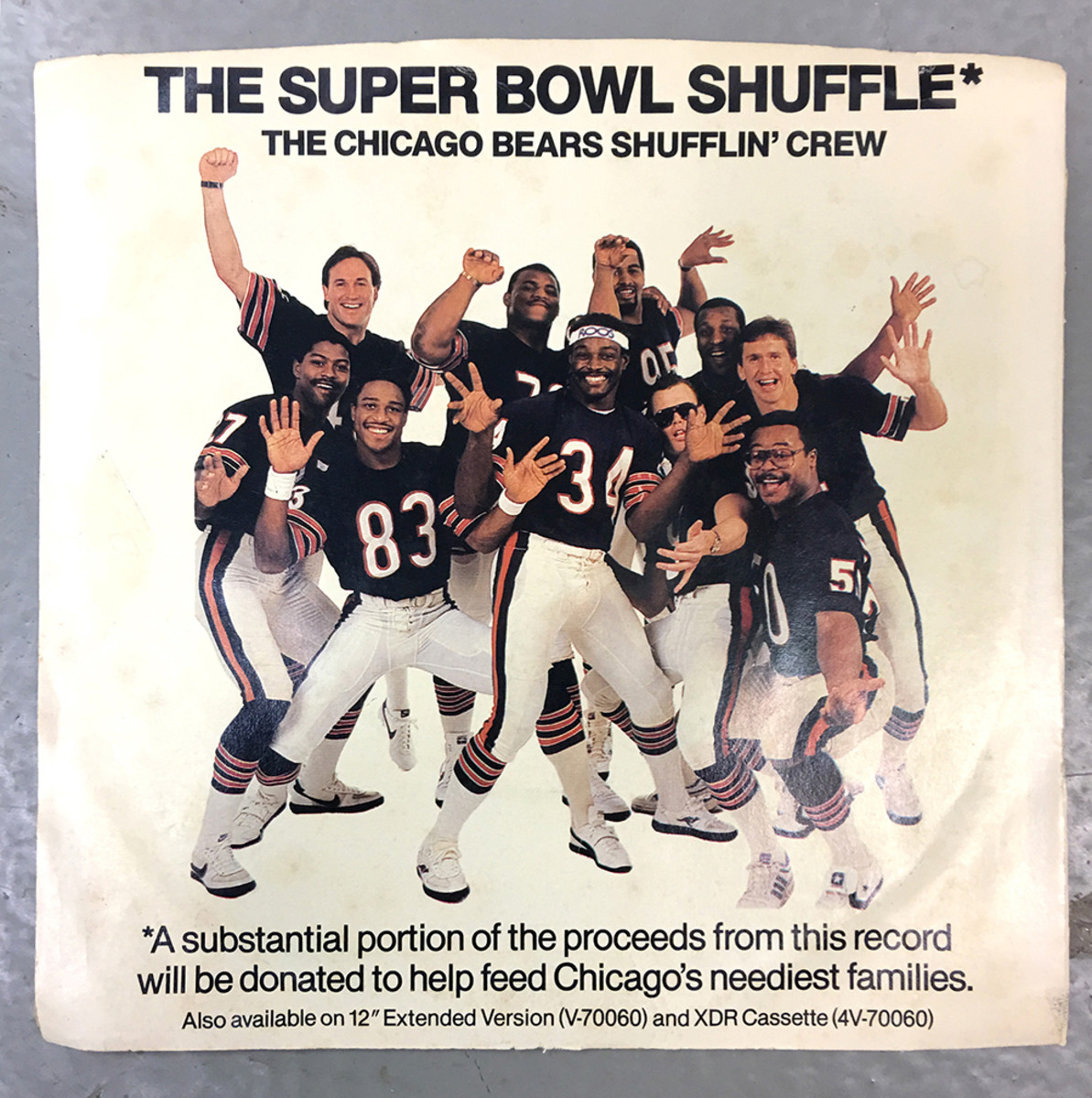

“The Super Bowl Shuffle” Record

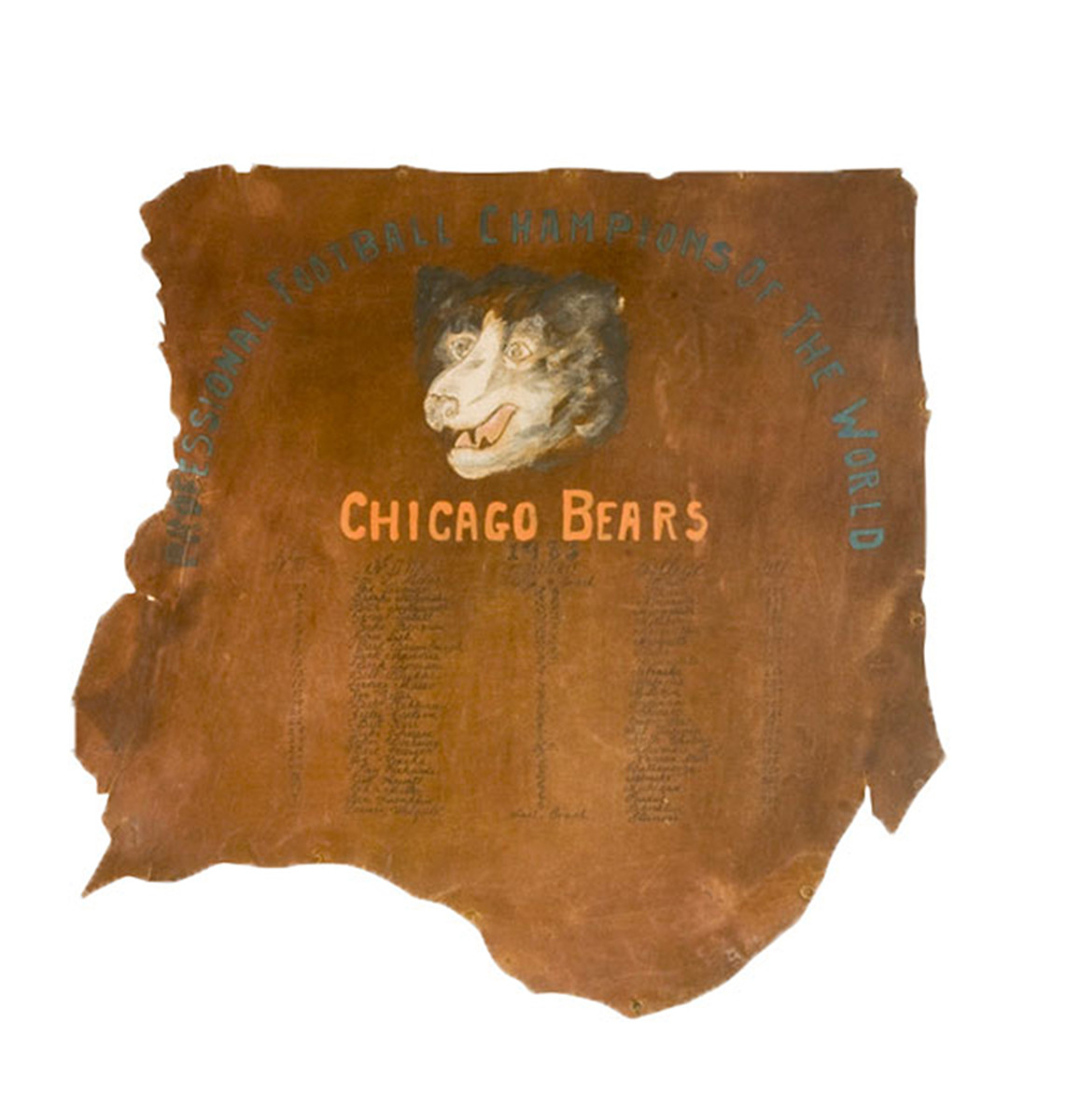

There will be eternal debate about the greatest NFL team of all time, but the ’85 Bears can claim one thing no other can: They produced a hit single.

Superstition be damned, the self-described Chicago Bears Shufflin’ Crew recorded the catchy “Super Bowl Shuffle” and accompanying video months before Super Bowl XX. Cocky? Sure. But that’s the way the ’85 Bears played, rattling off a 15-1 record with Walter Payton and perhaps the greatest defense ever. Receiver Willie Gault (and his swerving hips) spearheaded the music project with Red Label Records, recruiting nearly half the roster to join as rappers, backup dancers or the band. Payton was darn good at spitting rhyme, and most of the Bears were pretty bad at dancing. The jingle caught on, rising to No. 41 on the Billboard Hot 100 and selling around a half-million copies, with the profits designated for charity. But the Shuffle wouldn’t have its enduring place in history if the team hadn’t backed it up on the field. The Bears did so in convincing fashion, beating the Patriots by a historically lopsided score of 46-10 “to give Chicago,” as Payton had rapped, “a Super Bowl champ.”

The Shuffle’s success spawned a slew of imitators in subsequent years, from Mike Ditka’s Coach-tastic “Grabowski Shuffle” (in which Ditka extols the virtues of the common fan) to Key & Peele’s fabulous East/West Bowl Rap. But there’s just nothing to compare to the Bears’ trend-setting opus.

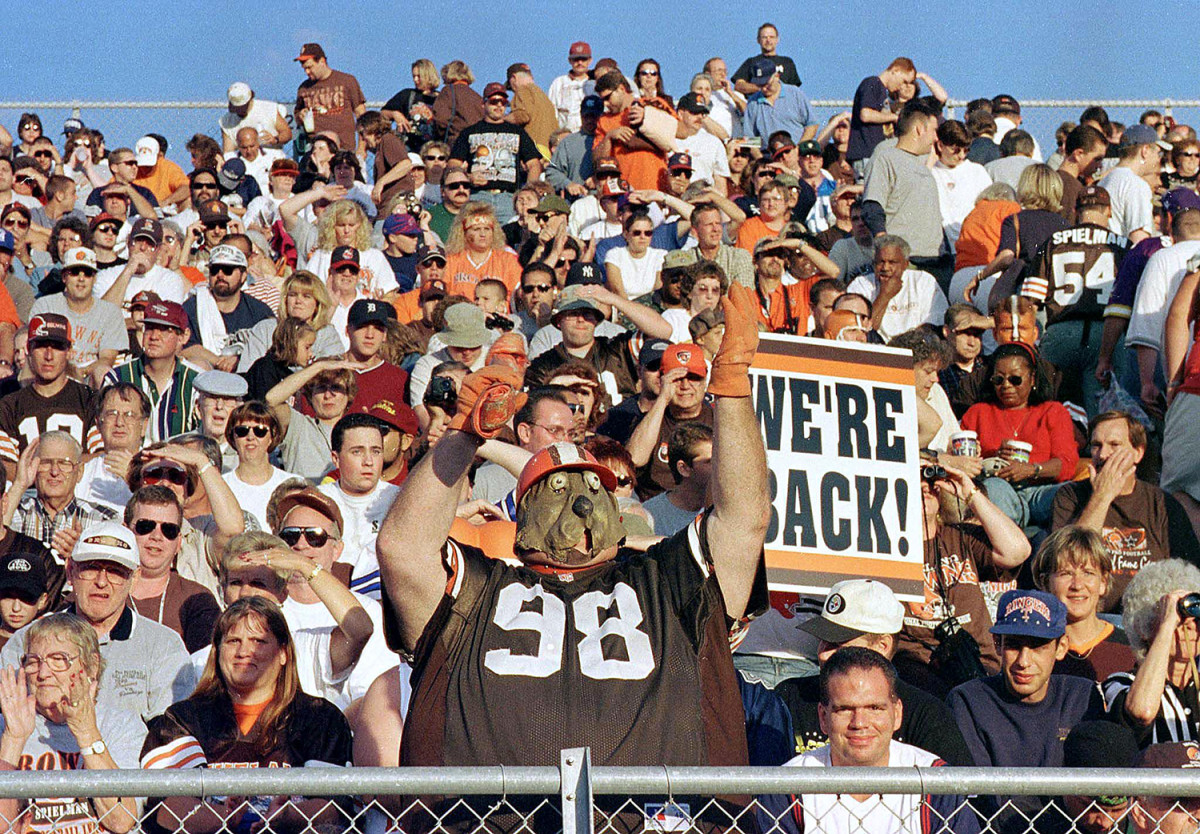

Big Dawg’s Dawg Pound Mask

The history of Cleveland’s Dawg Pound dates to 1985, when fans overheard two Browns cornerbacks, Hanford Dixon and Frank Minnifield, barking at their defensive line. Dixon called his fellow defenders the Dawgs to inspire them during the ’85 season, and fans ran with the idea. Barking was the first trademark of the Dawg Pound, but when John Big Dawg Thompson donned a dog mask, the fan section was given its face.

His nickname has no quotes around it—he legally added it as his middle name. In a way, that reflects just how important he is to the Browns. Thompson’s huge frame and droopy dog mask have served as the leading image for the Dawg Pound for decades. His passion and recognizable nature earned him a spot in the Hall of Fans in Canton, and his importance to the team allowed him to travel to Washington D.C. to lobby for the Browns to stay in Cleveland in the mid 1990s.

That effort failed, of course, as Art Modell moved the franchise to Baltimore in 1995. But it was because of fans like Big Dawg, Clevelanders fanatical about their football team, that the NFL knew it had to bring a franchise back to Northeast Ohio, which it did in 1999. To the average NFL fan, Big Dawg and his rubber mask are a fun novelty, but for Cleveland, he and his compatriots in the Dawg Pound represent the vital place the Browns occupy in the culture of the city.

Frank Reich’s 1993 Wild-Card Game Hand-Warmer

Beset by injuries, the Buffalo Bills were without their franchise quarterback (Jim Kelly), linebacker (Cornelius Bennett) and running back (Thurman Thomas) when they trailed the Houston Oilers, 35-3, at home in the second half of a wild-card playoff game on Jan. 3, 1993. What’s more, Houston had defeated Buffalo, 27-3, in the regular-season finale the week before. So it was no wonder that Bills fans (who didn’t sell out the game to begin with) headed for the exits early at Ralph Wilson Stadium.

But Kelly’s backup, Frank Reich, was just keeping his hands warm in the 24-degree wind chill that day. After falling behind by 32 points, Reich and Bills outscored the Oilers 38-3 to win, 41-38, setting the record for biggest comeback in league history.

It started innocently enough, with a 1-yard touchdown run by Kenneth Davis to make it 35-10. Then Bills kicker Steve Christie recovered his own kickoff (dubbed a mistake by coach Marv Levy), and a controversial 38-yard touchdown pass from Reich to Don Beebe made it 35-17 (replays showed Beebe stepping out of bounds). Three more Reich TD passes in seven minutes, one after a botched snap on an Oilers’ 31-yard field goal attempt, gave the Bills a 38-35 lead with 3:08 left to play. But Houston quarterback Warren Moon marched the Oilers 63 yards to set up the game-tying 26-yard field goal.

On the third play of overtime, Moon was intercepted by Bills defensive back Nate Odomes. After two runs, Christie booted the game-winning field goal from 32 yards out. Reich completed 21 of 34 passes for 289 yards and four touchdowns. He also led the Bills to a road win over the Steelers the next week but was replaced by the recovered Kelly in the AFC title game as the Bills advanced to their third straight Super Bowl. So much for the hot hand.

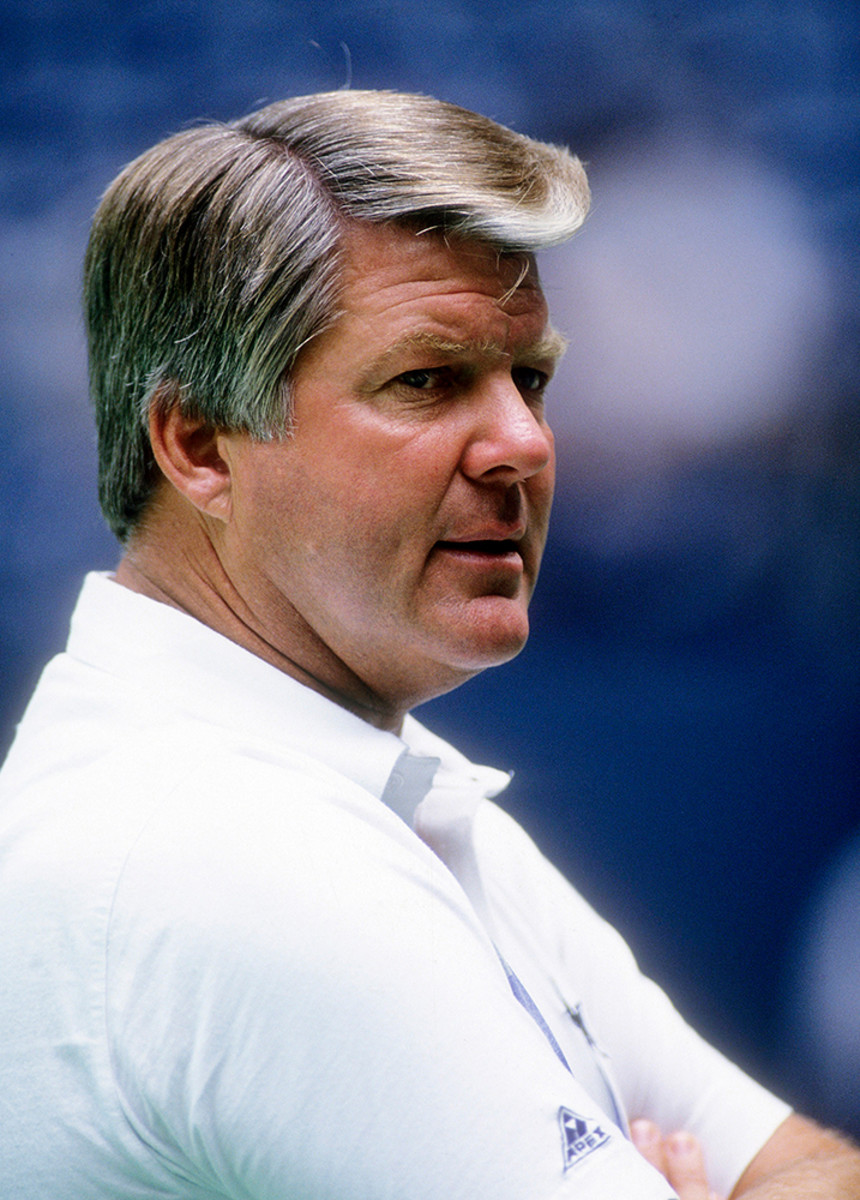

Jimmy Johnson’s Hair

Anyone who watched a Cowboys game in the early 1990s surely pondered this critical question: Does Jimmy Johnson’s hair move? That shiny swirl atop his head seemed to be locked in place—an all-too-appropriate symbol of those flashy, cocksure Cowboys teams he coached. Though he couldn’t take it with him on the sideline, the coach was known to carry a canister of Paul Mitchell Freeze and Shine Super Spray in his briefcase anywhere he went.

Jerry Jones bought the team in 1989 and replaced Tom Landry with Johnson, expecting Johnson’s success at the University of Miami to transfer to the NFL. The Cowboys stockpiled talent, drafting Troy Aikman in ’89 and Emmitt Smith a year later to form “The Triplets” along with receiver Michael Irvin. America’s Team won back-to-back Super Bowls in 1992 and 1993, but the power struggle between Jones and his coach resulted in Johnson’s resignation after the Super Bowl XXVIII win. Dallas won one more championship with Johnson’s building blocks, in 1995; Johnson’s coaching career, meanwhile, ended in ’99 after four unspectacular seasons with the Dolphins. His perfectly coiffed mane can be seen on Sundays in his role as an analyst for FOX Sports.

Drew Rosenhaus’s Cell Phone

Agent Drew Rosenhaus is seemingly always on his cell phone—even if some of the calls aren’t quite organic. Take, for example, the 2003 draft, when cameras zoomed in on Rosenhaus sitting next to his client, projected first-rounder Willie McGahee. As the picks rolled on, McGahee appeared nervous. Then the halfback’s cell phone rang—turns out, Rosenhaus was on the other line. “I didn’t want it to make it look like our phones weren’t ringing,” Rosenhaus told the AP afterward. “Willis and I had a little chat to create the perception that we weren’t waiting for teams to call us.” The Bills chose McGahee at No. 23.

Rosenhaus’ tactics are unconventional and at times controversial, but he perfectly illustrates the breed of super-agent that emerged in the NFL’s salary-cap era. In fact, agents like Rosenhaus have become so ubiquitous that it’s hard to imagine an NFL without them. (It did exist; Vince Lombardi famously frowned upon players who wanted to hire representation.)

Rosenhaus earned his accreditation at age 22, appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated eight years later and accumulated a roster of A-list clients for whom he has negotiated more than $2 billion worth of contracts. He did so by working tirelessly, making countless calls to general managers, players and anyone in between to maximize potential earnings. (Rosenhaus titled his autobiography A Shark Never Sleeps.) SI’s 1996 cover story deemed Rosenhaus “the most hated man in the NFL”—his detractors include rivals and former clients—though here’s something everyone might agree on: Listening in on his phone conversations would be priceless.

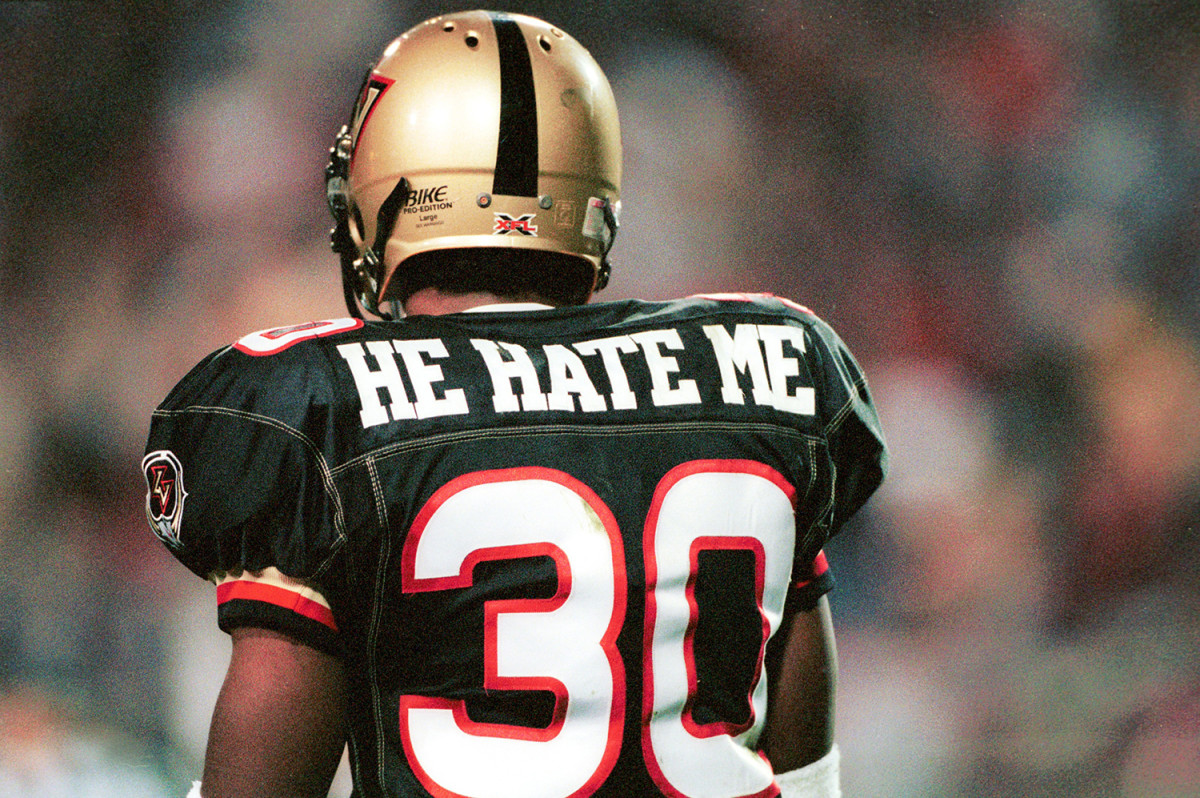

He Hate Me’s XFL Jersey

In case it wasn’t obvious that a Vince McMahon-led, WWE-influenced pro football league would be different from the NFL, there was the guy with “He Hate Me” on his jersey.

Rod Smart was the poster child for the XFL, the ill-fated extreme football venture that valued the outrageous. Teams had names like the Hitmen and Maniax while Smart, a running back for the Las Vegas Outlaws, drew plenty of attention with the moniker he decided to wear on his back for the league’s lone season in 2001. (Smart would go on to play six seasons in the NFL, making a Super Bowl appearance with the Panthers in ’04.)

With trash-talking stadium announcers, cameras in the huddle and no penalties for roughness, the XFL was mostly about entertainment. Instead of starting the game with a coin toss, a ball was placed on the ground and one player on each team was sent to grapple for it. The league opened with tremendous buzz, and the February-April schedule smartly complemented the NFL calendar, but the novelty quickly wore off. When the league folded, dozens of XFL alums went on to NFL careers, from Tommy Maddox to Steve Gleason to Paris Lenon, who was the last XFLer to play in the NFL, in 2013. Both the WWE and NBC lost millions on the league—the cost of challenging the almighty shield—but McMahon is planning to resurrect the league (minus many of its extreme elements) in 2020.

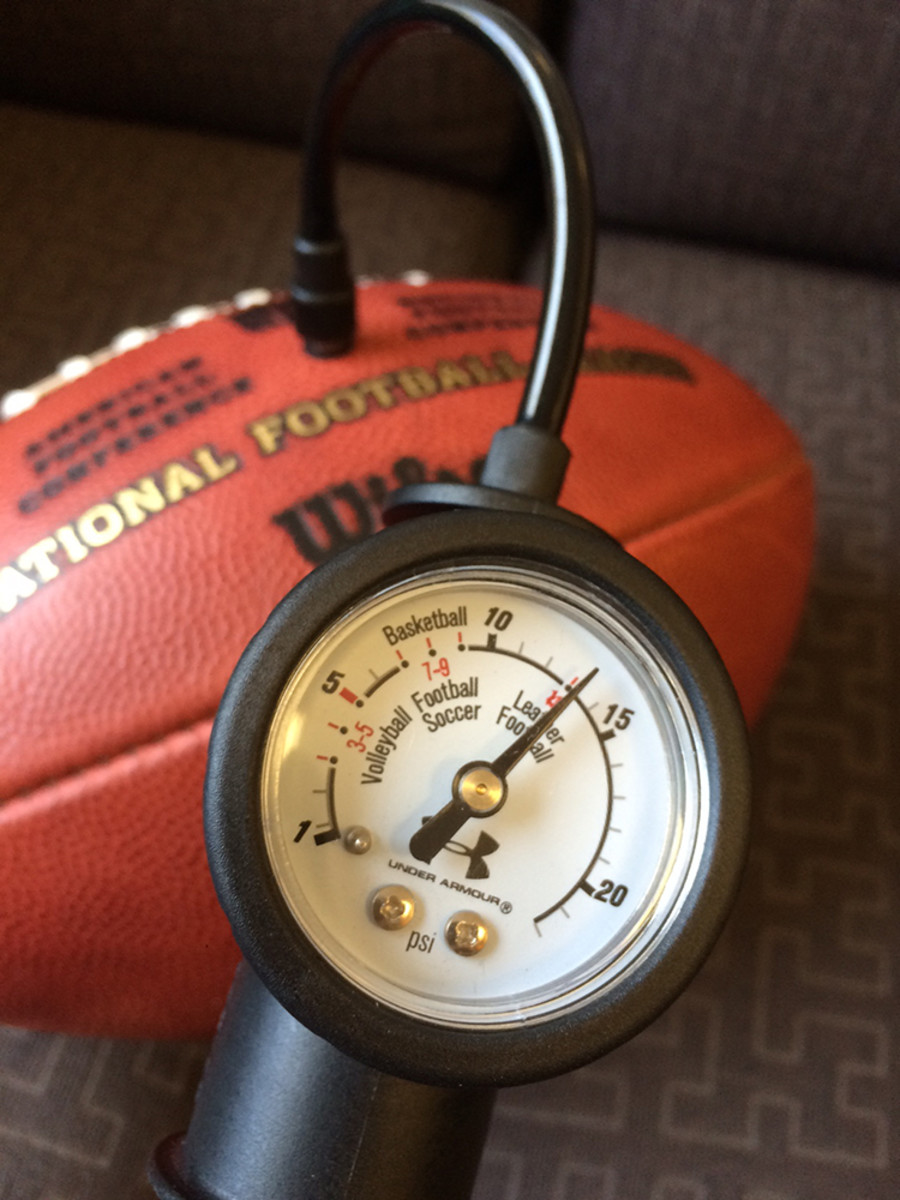

A Football Air Pressure Gauge

Regardless of where you stand on the divide between the Patriots and the rest of the world, there’s no denying that “Deflategate” was one of the wildest and most bizarre controversies in the history of American sports. Did Tom Brady and the Patriots conspire to deflate the footballs used in the January 2015 AFC title game against the Colts at Gillette Stadium, sucking the air out of the balls to make them softer and presumably provide the home team with a competitive advantage? Or was the hubbub prompted and promulgated by jealous opponents and a league looking to humble Belichick, Brady and the New England dynasty?

After a Colts interception in the first half, Indy staffers checked the ball and reportedly found it to be under 12.5 psi, the minimum pressure allowed by league rules. Concerns were expressed to referee Walt Anderson, and two alternate officials, using two separate gauges, checked 11 Pats’ balls at halftime, finding all of them under the 12.5 lower limit. A league investigation proceeded, litigation ensued, and Brady was ultimately suspended for four games, and the Patriots fined $1 million.

Never mind that the two gauges used did not agree on any of the readings, or that the league had never previously checked balls at halftime to see how environmental and playing conditions affected inflation levels, or that NFL vice president of football operations Troy Vincent admitted he was unaware of the Ideal Gas Law, the scientific principle that governs air pressure. Or that that Patriots actually did better after the balls were brought back up to regulation—scoring 28 unanswered points in the second half to win 45–10. The punishment would stand.

Throughout the process the NFL looked both petty and ignorant of basic science. MIT professor John Leonard was one of many who ridiculed the league’s arguments and testing protocols. After the saga played out, Brady ultimately sat out the first four games of the 2017 season—then led New England to a Super Bowl victory.

Mean Joe Greene’s Coke-Ad Jersey

The premise was brilliant: After he drank a Coca-Cola, Joe Greene would be revealed to America as a man who wasn’t so mean after all. The TV commercial captured viewers’ hearts when it aired in October 1979, and then again during Super Bowl XIV—the fourth championship won by Greene’s Steelers.

A cornerstone of Pittsburgh’s famed Steel Curtain defensive front, Mean Joe had a reputation that matched his hulking 6'4", 275-pound frame. But as he’s limping to the locker room in the commercial, more vulnerable than he’d ever been seen on the field, he’s offered a Coke by an awestruck kid and suddenly turns sunny. Greene tosses the boy his jersey while intoning the classic line, “Hey kid … catch!” Greene’s surge in popularity lasted well beyond his 13-year, 10-Pro Bowl career—and the fact that a Steelers player was picked to sell Coca-Colas (and a smile) meant something, too. The ’70s were the Steelers’ dynasty years, when Chuck Noll, Terry Bradshaw, Franco Harris and Greene won four championships together in six seasons, and the team’s tough, blue-collar image was embraced far beyond Western Pennsylvania.

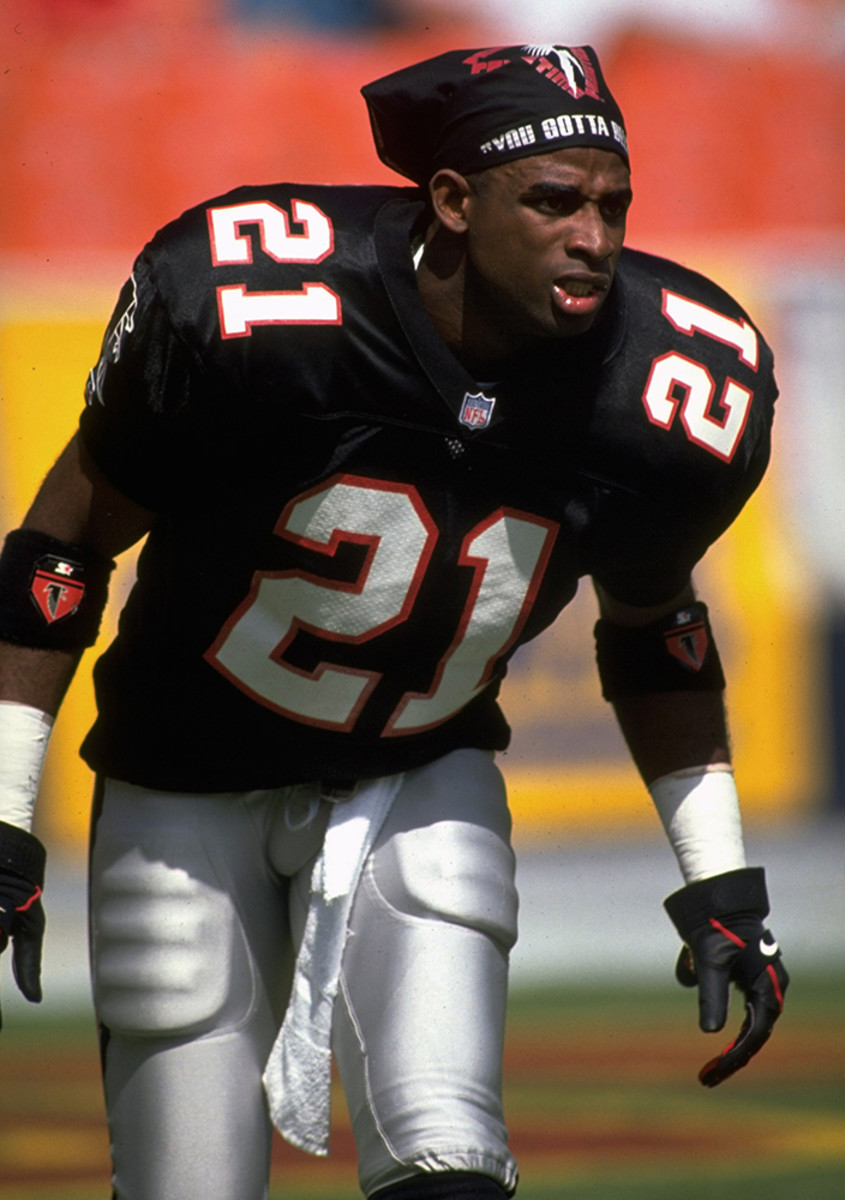

Deion Sanders’ Bandana

Who embodied the NFL in the 1990s better than Deion Sanders? Prime Time caught the self-promotion bug early; as a Florida State senior he showed up to a game against Florida in a tuxedo, via limousine. From the time he arrived in the NFL as a Falcon in 1989 until he left as a Raven in 2005, no player was louder, more talented or more divisive than Sanders.

“Neon Deion” says he gave up the flamboyant bit after a suicide attempt in 1997 and committed his life to religion. He gave hints about his fading taste for the spotlight earlier than that, telling the Associated Press in 1995, “In college, maybe you wanted the glamour and the limelight and all the interviews. But now I’d rather be away from it. Everybody wants exposure and endorsements and making a lot of money, but you can’t leave your hotel room… Once in my life, all this was cool. Now I just like to play the game and go home.”

In addition to the Falcons and Ravens, he played for the 49ers, Cowboys and Redskins, winning two Super Bowls and never spending more than five seasons in the same place. He changed bandana colors at each stop, famously breaking out a black one to tie around his Hall of Fame bust at his induction in 2011.

The AT&T Stadium Video Board

Leave it to Jerry Jones to build something that proves everything really is bigger in Texas.

The $1.3 billion AT&T Stadium, which opened in 2009 as Cowboys Stadium, resembles a palatial spaceship dropped into Arlington, in the middle of the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex. No feature represents the structure’s grandiosity more than the 160-foot-long HD video board suspended over the center of the playing field. It was Guinness World Record-size at the time of its construction, and though other venues have since unveiled larger ones, the Cowboys owner’s video board remains the most famous. The giant flashing display is part of the show at “Jerry World” and has been struck by punts on occasion.

Bigger, though, isn’t always better. Super Bowl XLV, intended to be the showcase for the Cowboys’ mansion, instead turned calamitous—the incompletion of temporary seating areas left 400 fans without seats, and falling ice outside the stadium injured six people two days before the game. More disappointing for the Cowboys, while the flashy digs have hosted a Super Bowl, they have yet to see an NFC Championship Game.

Joe Namath’s Knee Brace

The white fur coat might have been his most famous accessory, but the knee brace was Broadway Joe’s most important.

The history Joe Namath made for the New York Jets, after all, depended on him playing on those wonky knees. His right knee was already gimpy when he signed his superstar-making $427,000 contract (record-setting money in those days) as the No. 1 pick in the 1965 AFL draft. Just a few weeks later, Jets team orthopedist James Nicholas operated on Namath for the first time, to fix the injury he’d suffered during his senior season at Alabama. Nicholas fashioned a special brace to protect Namath’s knee, with the help of Lenox Hill Hospital’s brace shop, and told the rookie quarterback he might be able to play four years.

Namath went on to play 13 seasons, though his knee problems only got worse—he needed four operations during his time with the Jets (two on each knee) and years later had a double knee replacement. That fourth season, though, did end up being significant: That was 1968, the year Namath made his famous guarantee to upset the Colts in Super Bowl III—still the Jets’ only championship.

The Monday Night Football Blazers

Looking back on the lunacy that was the beginning of ABC’s Monday Night Football, those garish yellow blazers worn by the broadcasters and pioneered by the Wide World of Sports crew were the least outrageous thing. The day it was played, Monday, was an affront to some—weekday football had yet to be embraced by the public. Three announcers instead of two seemed excessive. And nine cameras instead of four? Sensory overload. ABC Sports president Roone Arledge’s plan: treat Monday Night Football like the Olympics.

We know now it was a pretty good idea. NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle sold a yearlong package beginning in 1970 to Arledge and ABC for $8.5 million, only after Sunday broadcast partners NBC and CBS passed on the unconventional football slot. Those same rights cost ESPN $1.1 billion in 2005. With the 500th broadcast in 2002, Al Michaels and John Madden donned the same canary yellow made famous by ABC’s original crew of Keith Jackson, Howard Cosell and Don Meredith.

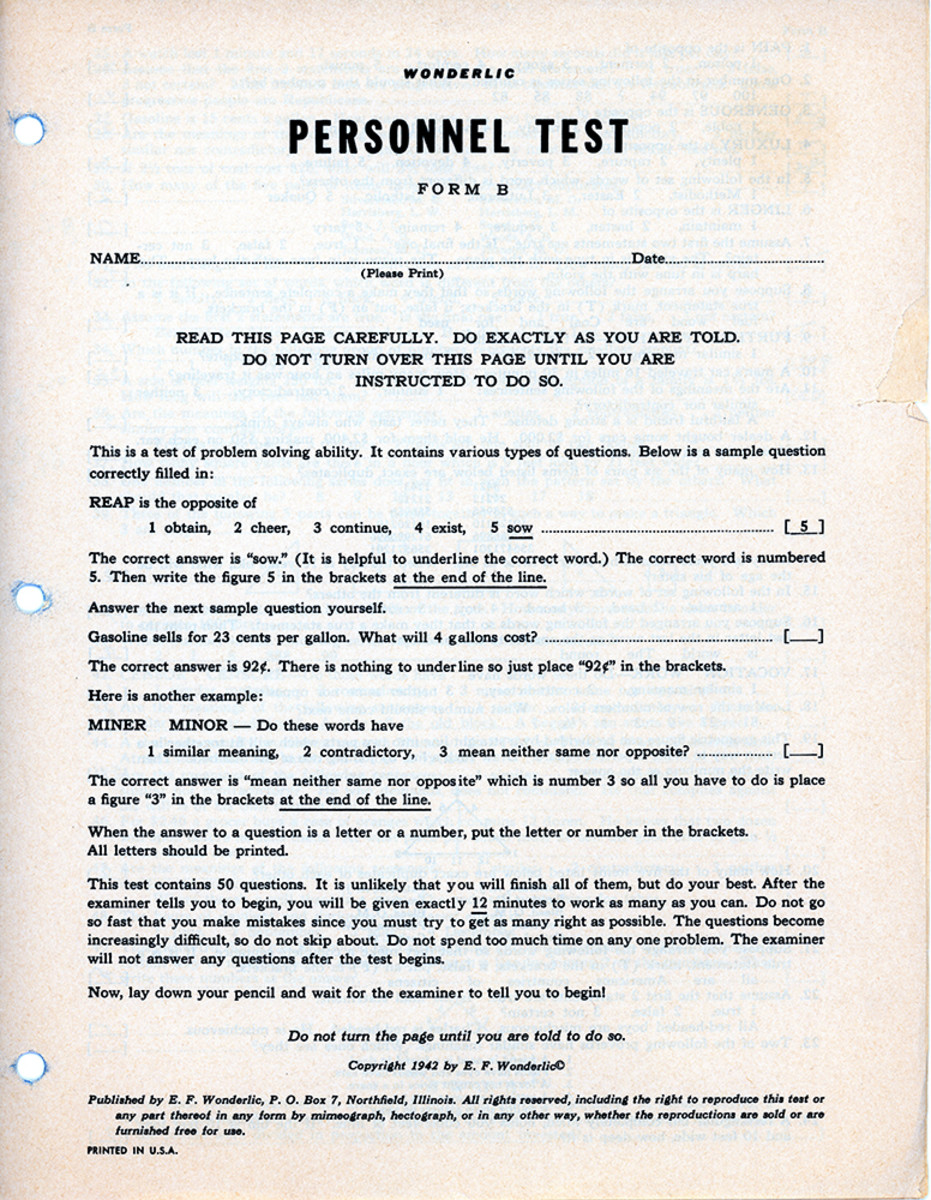

The Wonderlic Test

The SAT is to college as the Wonderlic is to … ?

Answer: The NFL, for those brushing up on their analogy skills.

The 50-question, 12-minute test administered at the scouting combine is an entrance exam of sorts for the NFL—even if the scores aren’t publicly released and its impact on the draft is both uncertain and varied. The test was developed in the 1930s by a Northwestern graduate student, E.F. Wonderlic, as a short-term cognitive exam with which companies could screen potential employees. Cowboys coach Tom Landry is credited with introducing it to the NFL in the 1970s, to assess the mental aptitude of prospects. Test-takers answer questions related to math, vocabulary and reasoning, and receive a score between 0 and 50. The link between a player’s score and his career outlook is hotly debated, as are the ethics of teams or individuals leaking players’ results to the media. NFL teams have explored other means of testing a player’s off-field cognitive capabilities, but the Wonderlic is fast and simple—and, like the 40-yard dash, has been a customary part of the pre-draft mystique that builds every spring.

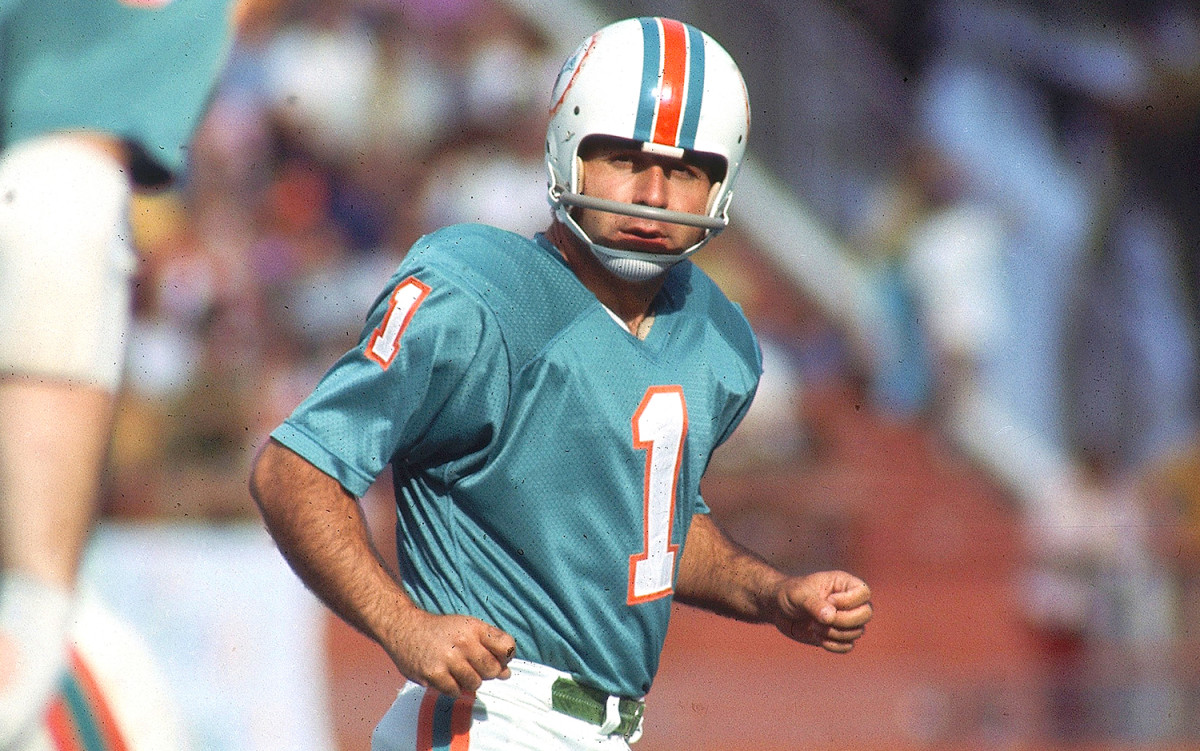

The Single-Bar Face Mask

Wearing full-cage face masks, some players are virtually unrecognizable on a football field. But it didn’t used to be that way.

Into the early 1950s, most players didn’t wear face masks at all, except for a few improvised materials that first appeared as early as the 1920s. The dedicated face mask wasn’t born until Cleveland Browns coach Paul Brown asked equipment manager Leo Murphy to come up with a device that would allow star quarterback Otto Graham to remain in a game in 1953. Graham had suffered a lacerated mouth, and soon after, Brown devised a mask that could be permanently affixed to the helmet.

Other teams adopted the practice and the face mask largely became part of the NFL uniform by 1955. Different species were created, and soon players became recognized by their distinct face wear, from Ernie Stautner’s beak-like model produced by Marietta to Larry Csonka’s nose guard. But some players continued to hold true to the old single-bar, preferring the better sightlines into the 1980s and beyond. Former Redskins quarterback Joe Theismann was the last non-kicker to wear the single bar, up until his retirement in 1985.

The single-bar face mask was officially ruled illegal in 2004, though players who wore it previously were grandfathered in. On Oct. 7, 2007, it made its final appearance on an NFL field when Scott Player of the Browns punted five times in a 34-17 loss to the Patriots at Gillette Stadium. That was the last game for Player, who was the last to wear the single bar. He was released the following training camp by the Patriots and their football history-loving coach, Bill Belichick.

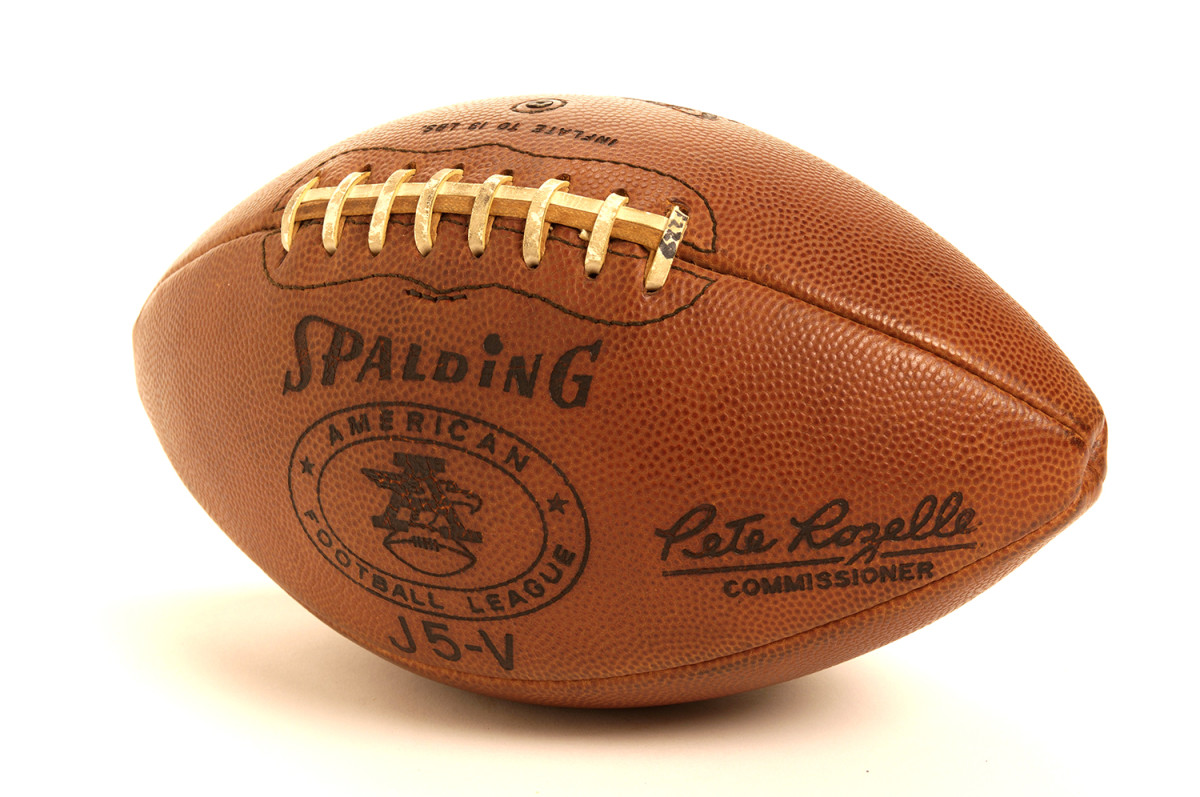

The AFL’s Skinny Football

Beloved by the likes of Len Dawson and George Blanda, the upstart American Football League’s official game ball—the J5-V by Spalding—was only a quarter-inch skinnier and longer than “The Duke” produced by Wilson and used by the NFL, but it represented to players the key difference between the two leagues.

Dawson and Blanda led vertical passing games envied by young AFL fans such as Terry Bradshaw, who, according to Ed Gruver’s historical account The American Football League, cherished his Spalding J5-V Christmas gift from his father as a 9-year-old. The AFL’s early popularity among young people stemmed from the wide-open offensive play, but that had less to do with the ball and more to do with the anti-establishment disposition of the Foolish Club, the adopted nickname of the AFL’s eight owners who eventually merged with the NFL in 1970.

The most significant transformation for the football happened in 1875, when college rules dictated the ball be egg-shaped, for carrying, rather than spherical, as it had been for the first seven years since the College of New Jersey and Rutgers played what is considered the first game in 1869. In 1912 the all-important circumference was defined and reduced to 22 1/2 inches. Still, it took several decades until long-fingered pioneer quarterbacks like Sammy Baugh redefined throwing accuracy. (At his first NFL practice in ’37, Baugh was challenged to hit a Washington receiver in the eye. Baugh asked, “Which eye?”). With the early success of “Slingin Sammy” and a long line of others, the ball grew ever svelter, eventually reaching the 21 1/4 inches mandated by the NFL today.

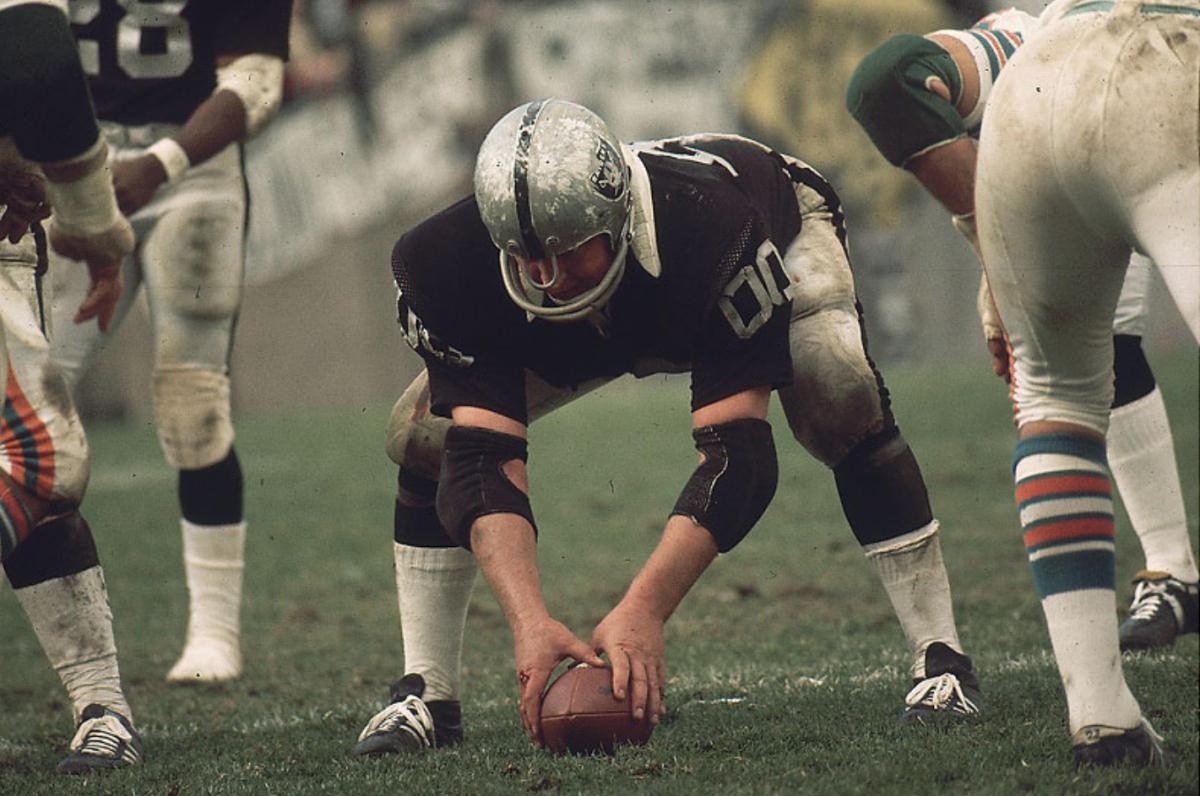

Jim Otto’s Helmet

As the NFL prepared for its 100th season, Oakland Raiders headwear was a hot topic, with receiver Antonio Brown fighting to keep the model he’s worn since entering the league in 2010 but which no longer meets the NFL’s upgraded safety standards. Brown might ask Raiders all-timer Jim Otto whether he’d have sacrificed familiarity for better protection.

Otto, a 10-time All-AFL selection and Pro Football Hall of Famer, played 15 seasons at center for the Raiders, 223 consecutive games’ worth of bashing and banging in the trenches. The man known as Double O “had a massive Prussian head, a perpetual sneer, and dark, menacing eyes,” author Gary Pomerantz wrote. “His nose, broken more than 20 times, curved like the letter ‘S,’ and his wife sometimes rearranged it in the stadium parking lot after games as if it were living room furniture. He wore a size 8 helmet, big as a bucket, largest on the Raiders, a battlefield relic with the signature pirate with an eye patch on its side covered over by a white splotch—the paint scratched off from Otto’s violent collisions with the likes of Curley Culp, Ernie Ladd, Buck Buchanan, Merlin Olsen and Mean Joe Greene.”

The price of all that punishment, inflicted and endured, was steep. “There were so many times that I would walk off the field and my eyes would be crossed,” Otto said in 2012 for Frontline’s League of Denial documentary. “Did you ever have that happen to you? Get hit in the head so hard your eyes were crossed? … Or what about if you had amnesia for two days? When you looked at your wife and you didn't know who she was, like, who’s this chick? And you couldn’t remember.” Otto related one play in which Packers linebacker Ray Nitschke shattered his helmet and facemask, breaking his nose, cheekbone and zygomatic arch and detaching his left retina, leaving Otto blind in one eye for six months. He didn’t even leave the game.

Otto said he suffered more than 20 concussions, no thanks to the rudimentary plastic helmet with sparse foam padding common in his era. And it wasn’t just his head. Double-0 underwent 74 surgeries, including 28 on his knees, as well as multiple joint replacements. In 2007, after several serious bouts with infection related to the surgeries, he had his right leg amputated. “I went to war, and I came out of the battle with what I’ve got,” he told Frontline. “And that’s the way it is.”

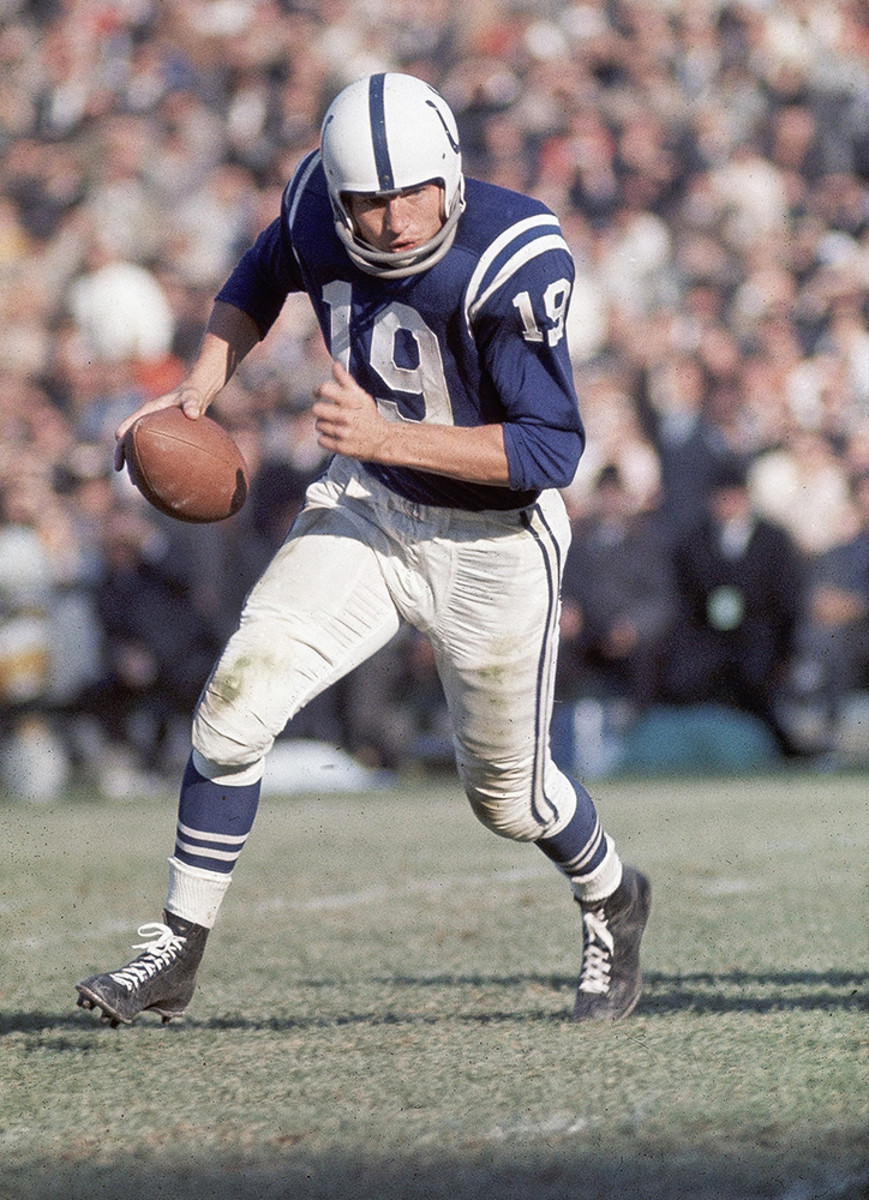

Johnny Unitas’s Black High-Tops

The shoes were black high-tops with long spikes and white laces. Johnny Unitas wore them for as long as he was a Baltimore Colt.

Even in the 1970s, when football fields were combed and trimmed like putting greens and even the linemen wore low-cut cleats, Unitas still wore the high-tops. He had to compromise though, in 1973, when the Chargers sported uniform powder-blue low-tops. The team ordered two pair special for Unitas and defensive tackle Dave Costa, who told Sports Illustrated’s Tex Maule he was a member of the “high-top society” chaired by Unitas. Said Johnny with a grin, “Jim Thorpe left me his shoes. They keep my ankles together.”

The high-top was resurrected in the 2013 season in the form of Carolina quarterback Cam Newton’s Under Armour super-high-tops, but it’s Unitas’s legacy of pushing the aerial envelope and putting the NFL on the map that endures more than 40 years after his retirement and 12 years following his death. Back when ground-and-pound offenses lacking modern-day finesse were all the NFL had known, Unitas led Baltimore to victory in the 1958 NFL Championship Game with 314 passing yards and a breathtaking two-minute drill. “You have to gamble or die in this league,” Unitas told Maule in 1959, weeks after the title match that was dubbed “The Greatest Game Ever Played.” “I don’t know if you can call something controlled gambling, but that’s how I look at my play-calling. I’m a little guy, comparatively, that’s why I gamble. It doesn’t give those giants a chance to bury me.”

Music from NFL Films, Vol. 1

On the back windowsill of NFL Films czar Steve Sabol’s office—which was preserved after his passing in 2012—sits a row of binders, many containing memos to his staff. One undated sheet, which features a large cartoon of a gladiator blowing a French horn, is headlined: “We need more inspirational music in our films. Heart-stirrers, pulse pounders!” Pick up a copy of Music From NFL Films, Vol. 1, and you’ll know exactly what Sabol was seeking.

NFL Films, a catalyst in mythologizing pro football, produces more than 1,000 hours of programming per year. Each show presents the sport through the lens of human drama, with its hallmark style of tight, low-angled shots, slow-motion action, exclusive sideline access and poetic prose. Binding it all together is the music. The orchestral sounds of Sam Spence evoke images of troops preparing for battle, spaghetti Westerns or grand literary romances. But if you close your eyes and listen to tracks such as “Gut Pride” or the up-tempo, jazzy “Ramblin’ Man from Gramblin’,” you might also see a football field.

Combined with booming narration from John Facenda (many of his scripts penned by Sabol), this soundtrack reveals how Americans began to appreciate football not only as a game of X’s and O’s but as a stage for human struggle and success. The tracks are heart-stirring, pulse-pounding and everything we have come to love about the sport.

The Gatorade Bucket

There’s some dispute as to whether the Gatorade dunk started with the Bears in 1984 or the Giants in ’85, though it’s clear the Giants were most responsible for the tradition that stands today.

Teammates Jim Burt and Harry Carson turned the Gatorade bath of coach Bill Parcells into a special form of celebration on New York’s road to Super Bowl XXI. Parcells’ bonhomie in the matter didn’t hurt. When the season was over, the Giants having defeated Denver in Super Bowl XXI, Gatorade thanked Carson and Parcells for all the free publicity with $120,000 for the coach over three seasons and $20,000 to put Carson on a Gatorade poster, according to Darren Rovell in his 2005 book First in Thirst: How Gatorade Turned the Science of Sweat Into a Cultural Phenomenon.

“It’s really remarkable that people haven’t found anything else to do,” Rovell told the Washington Post in 2012. “The bullpen car is gone in baseball. Or how many people are really putting on eye black? Sports traditions don’t really last anymore.”

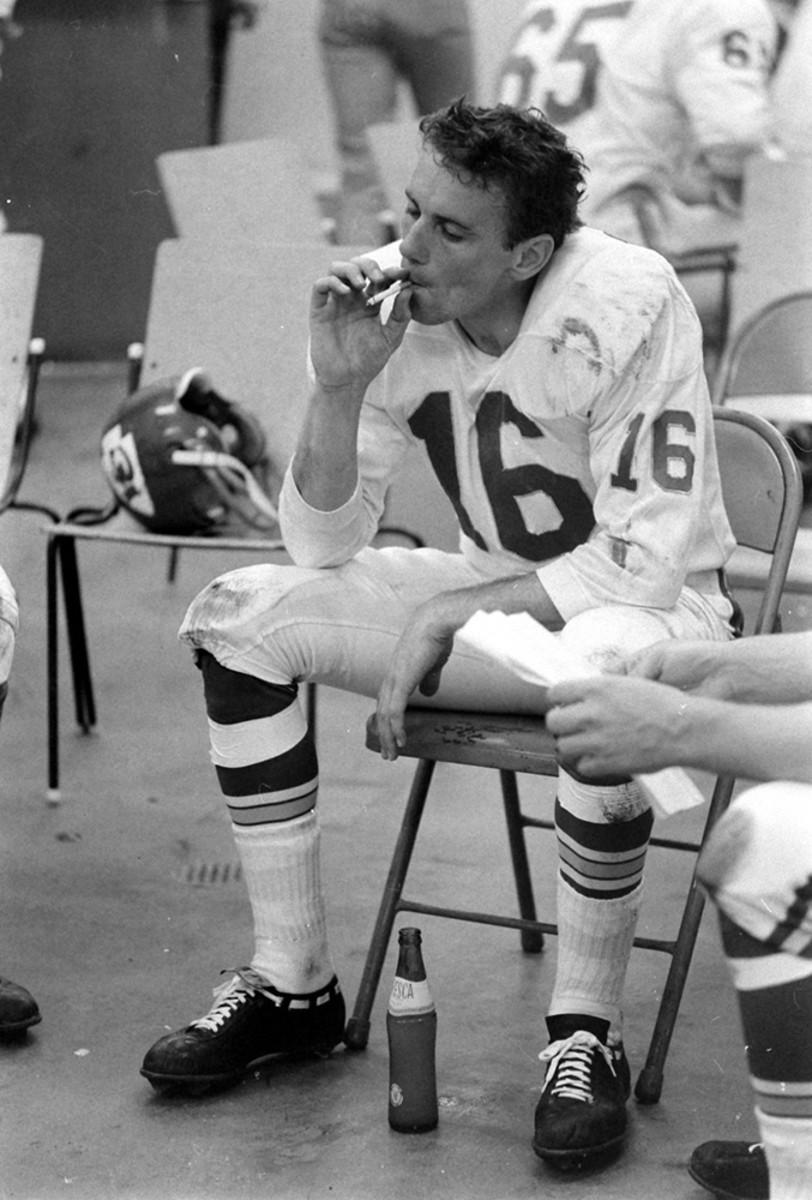

Mike Ditka’s Cigar

They don’t build ’em like the ‘85 Bears anymore. That started at the top with coach Mike Ditka, the gruff former NFL tight end whose penchant for cigars rubbed off on his team.

Ditka was beloved in the Windy City after a playing career that included Chicago’s NFL championship in 1963. He returned in ’82 as the Bears’ coach and made good on his promise to bring the team another title in short order. Ditka’s feud with defensive coordinator Buddy Ryan was as famous as Ryan’s 46 defense, but that simply added to the personality of a team that was cocky and fun-loving.

Ditka was often seen lighting up a cigar, and they were passed out in the locker room after the Bears blanked the Rams 24–0 in the NFC Championship Game. Chicago’s 46–10 demolition of the Patriots in Super Bowl XX two weeks later called for an even bigger celebration: cigars and champagne for one of the greatest teams of all time.

Though Ditka worship was at first limited to Chicagoland, his godhood went national with Saturday Night Live’s now legendary ”Superfans” skits—the cigar featured prominently, as did the trademark Ditka ’stache, the aviator shades and mounds of sausage. More than two decades after it first aired, the bratwurst-loving, Ditka-philic Superfans was resurrected in a series State Farm commercials. Talk about a legacy.

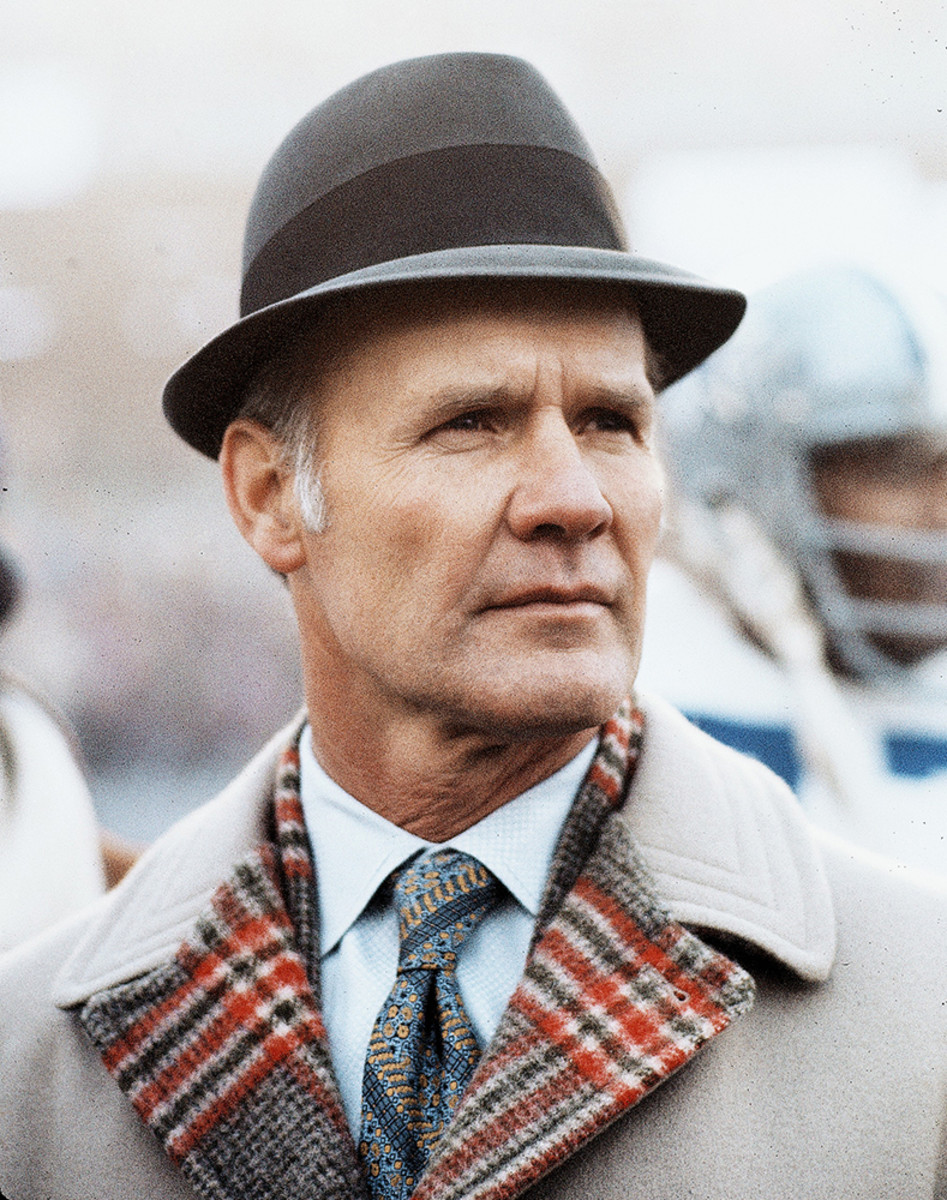

Tom Landry’s Fedora

Tom Landry always wore his Sunday best on the sidelines: suit, tie and his famous fedora. It was fitting for a man who always expected the Sunday best from his team.

The native of Mission, Texas, coached the Cowboys for 29 seasons. Under Landry’s watch, Dallas had a winning record in 20 straight years, from 1966 to 1985—a feat no other club has matched—and made five trips to the Super Bowl, winning twice. Landry won because he innovated, developing the “flex” variant of the 4-3 defense and popularizing the shotgun formation, allowing him to go toe-to-toe with contemporaries like Vince Lombardi and Don Shula. In fact, Shula, one of only three NFL coaches with more career wins than Landry’s 250 (George Halas and Bill Belichick are the others), considered Landry’s Cowboys to be the toughest foe he faced.

Landry played pro football in New York (with the Yankees and Giants) and began his coaching career there, too, as the Giants’ defensive coordinator in the late 1950s. But he returned to his home state in 1960 to make a star of the Cowboys. A Stetson would have been the obvious choice of headwear, but his fedora matched his memorably stoic demeanor. It was an unusual style, but it worked.

A Hy-Vee Shopping Bag

Before Kurt Warner caught on with the Rams, sparking a storied pro career that included two league MVP awards and a Super Bowl title, it was all nearly derailed by a spider. We all know the story of Warner bagging groceries and stocking shelves at a Hy-Vee in Cedar Falls, Iowa, before catching his big break. But did you know an arachnid’s bite interrupted plans for an NFL tryout a year earlier?

After two seasons with the Arena League’s Iowa Barnstormers, Warner earned a shot with the Chicago Bears but couldn’t attend the tryout after suffering a spider bite on his honeymoon. The Bears went another way, and the Rams came calling a year later. (Efforts to locate the spider were unsuccessful, so we went with the grocery bag.) Warner took the Rams to two Super Bowls, and bagged another Big Game trip with the Cardinals.

Warner is far from the only NFL great with a bizarre how-I-made-it story: Colts legend Johnny Unitas famously hitchhiked back to Pittsburgh from Steelers training camp, opting to save the bus fare the Steelers forked over after cutting him. He played semi-pro ball for $6 a game before getting his shot with Baltimore. The humble Warner can certainly relate.

“The Dirty Dozen” Movie Poster

JIM BROWN QUITS FOOTBALL FOR THE MOVIES

The Associated Press headline wasn’t exactly true. Jim Brown quit football at 30 years old for Jim Brown, as he would later tell it. For starters he was bored, just a few months after winning the league’s MVP award for 1965. “I wanted more mental stimulation than I would have had playing football,” he said on July 13, 1966, the day of his retirement. And Brown, then the NFL’s all-time leading rusher, didn’t want to fade away in the manner of a Joe Louis or, later, a Muhammad Ali. “People had sympathy for them,” Brown would say in coming years, “and you should never have sympathy for a champion.”

And yes, he wanted to be a movie star. The Dirty Dozen, a World War II action film about a group of Army convicts who are turned into an elite commando unit for a suicide mission, set him on the right path: Brown filled director Robert Aldrich’s vision for the first militant black hero in an action film. As modern-day movie critic Gary Susman notes, before Brown’s Robert Jefferson role, audience-friendly black characters typically turned the other cheek. Jefferson, on the other hand, slugged a character who called him a “n-----.”

Dirty Dozen co-star Ernest Borgnine wrote years later that Aldrich was urged by MGM execs to drop Brown’s death scene, in which he is gunned down after laying waste to a chateau full of German officers. The film would win an Oscar, they told Aldrich, if he cut it. He refused, and the scene upset audiences across the nation. In that way, Aldrich’s film seemed to mimic Brown’s unpopular and unexpected choice to leave football after nine brilliant seasons. Dozen character Samson Posey, played by Clint Walker, may have said it best: “I reckon the folks’d be a sight happier if I died like a soldier. Can’t say I would.”

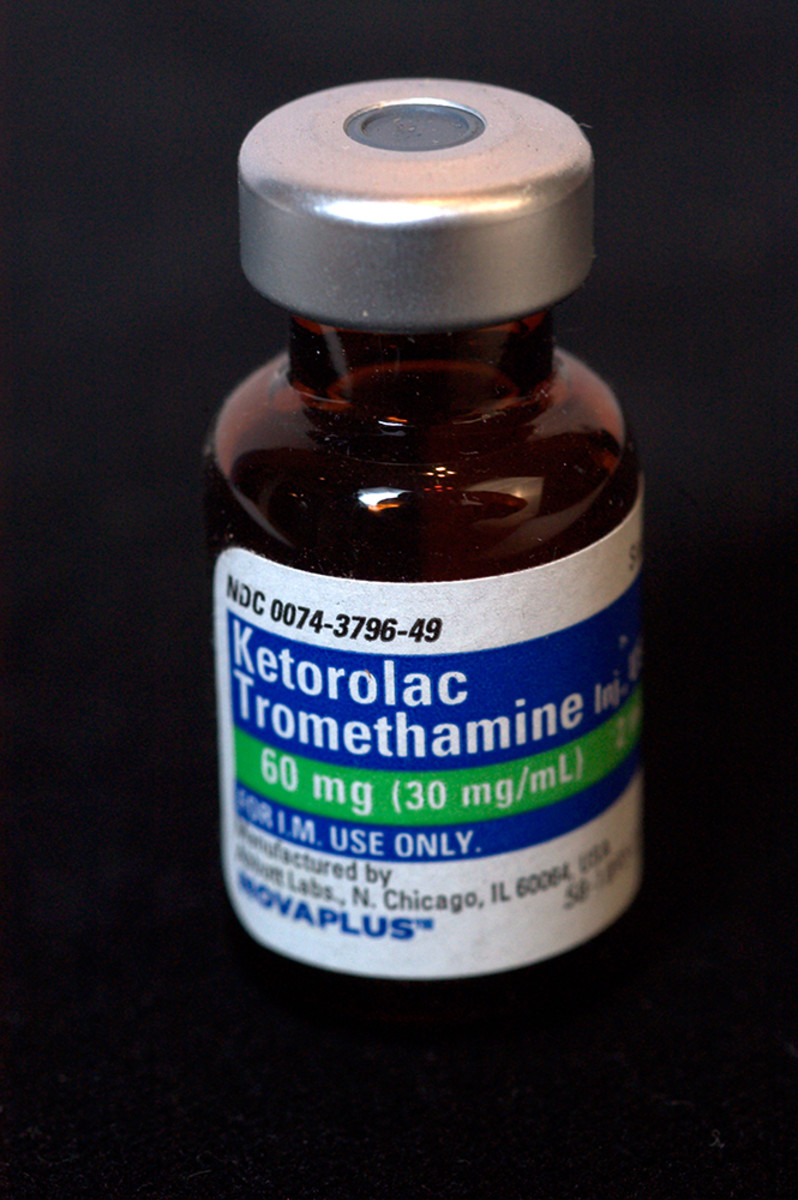

A Bottle of Toradol

The drug comes in pill form, but inject 30 to 60 mg into the butt and it will act even faster. Regular use could lead to gastrointestinal bleeding and kidney damage. Ketorolac Tromethamine (better known as Toradol) may sound dangerous, and it very well might be. But after being approved by the FDA in 1989, it became the NFL’s go-to wonder drug, an amped-up Aleve that numbs the pain—even if the pain doesn’t exist yet. As former Bears linebacker Brian Urlacher famously told HBO’s Real Sports in 2012: “It’s normal. You drop your pants, you get the alcohol [swab], they give you a shot, put the Band-Aid on and you go out and play.”

In a violent sport that lauds toughness, pain management has always been a complex issue. That’s why Toradol’s prevalence isn’t surprising. While the non-narcotic is not physically addictive, some doctors have raised questions about its long-term effects, especially when served with a cocktail of other drugs. Whether players are properly clued in on that is murky as well as a springboard for several lawsuits. Although some teams shy away from Toradol and other powerful painkillers, the ritual of players lining up for a pregame syringe has been commonplace for decades. Its full impact is still cloaked, for now.

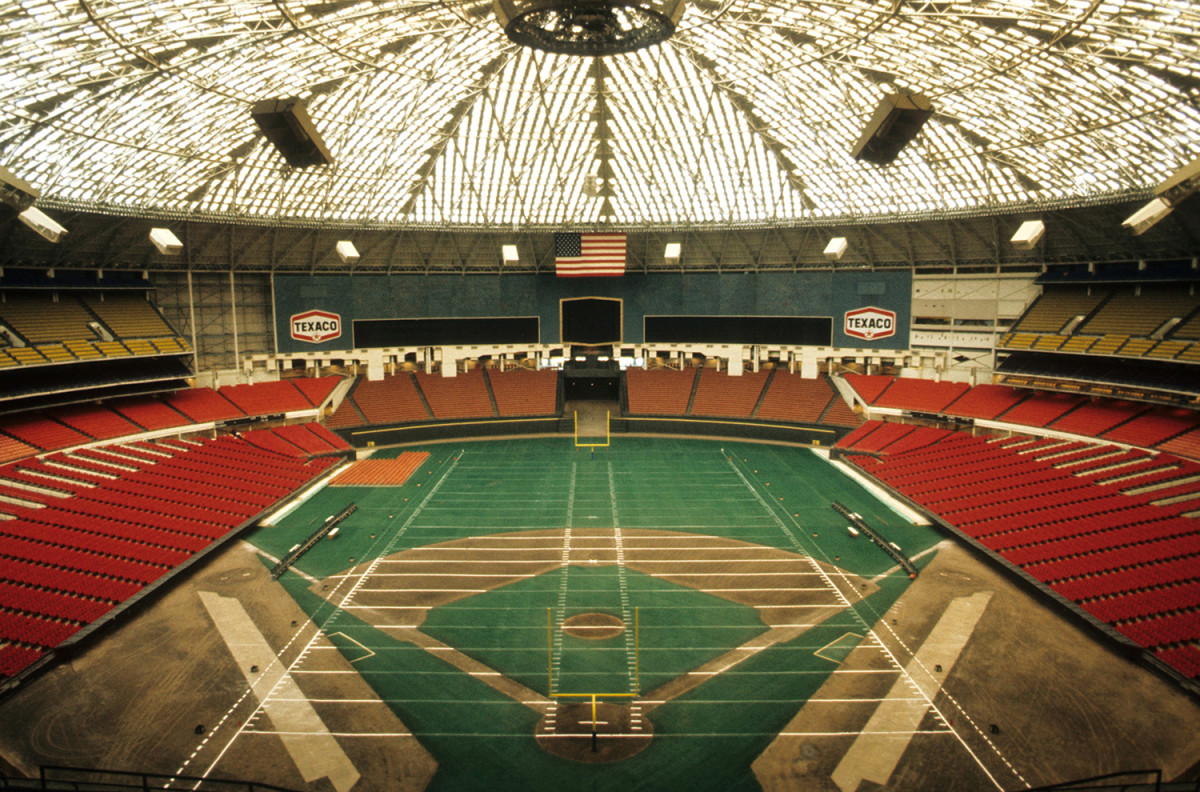

The Astrodome Roof

Here sits the first domed stadium, gutted and unused but preserved—for now. Unique in every conceivable way, from luxury boxes decorated like living rooms to a $2 million scoreboard, the Astrodome opened in 1965 with an exhibition game between baseball’s Yankees and the Astros (formerly the Colt .45s, rechristened that year) watched by President Johnson and his wife, Ladybird, from the owner’s skybox. The “Eighth Wonder of the World” became home to the Oilers in 1968 and served both teams into the late ’90s, when the football team left for Tennessee and the baseball team into a new park.

When the NFL came knocking again with a new team in Houston the early 2000s, a retractable roof stadium went up right next to the old Astrodome. While the Astrodome has mostly sat idle for more than a decade and its future is unclear—it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is a Texas antiques landmark, but recent plans to turn it into a parking garage and multi-use venue hit a snag over cost—its legacy permeates the NFL. The Astrodome gave us Astroturf, guarded the field from the elements and introduced a new way to play football: fast, fast, fast. How would Warren Moon’s run-and-shoot Oilers have fared on natural grass chewed up by a season of football in the heat of Houston? Would the Greatest Show on Turf, the Kurt Warner-led Rams, have reached those unprecedented heights if not for the Edward Jones Dome, one of the Astrodome’s many progeny? Would Randy Moss have been great on the frozen tundra of old Met Stadium in Minnesota, or did the fast track of the Metrodome help him in December when it was 72 degrees inside instead of 2 degrees outside?

Traditionalists will argue that domes deprive us of the very conditions—ice, snow, fog, mud—that have given the game some of its most memorable moments. Whether that’s good or bad might depend on how you feel about watching football in sub-zero wind chill or sweltering humidity, versus the cool comfort of climate control.

The Colts’ Mayflower Trucks

Late Baltimore Sun photographer Lloyd Pearson, a travel nut who guessed he’d crossed the U.S. 73 times in 25 cars and was engaged to his sweetheart within weeks of meeting her after their WWII pen-palling, caught perhaps the most iconic photo of a team leaving behind a city in American sports history.

Early during the morning of March 28, 1984, with Phoenix representatives turning away Bob Irsay and his Colts and the Maryland state legislature on the verge of giving Baltimore eminent domain over the team, Irsay and Indianapolis mayor William Hudnut pulled the trigger on a move that would shake up the NFL and help shape its future: The Colts were headed to Indy. Mayflower, the trucking company chaired by Hudnut’s friend and neighbor, offered to do the move for free, enlisting a stable of Sigma Chi brothers from the University of Maryland to pull off the secret midnight escape. Word got around Baltimore, and Pearson, who died in 2012 at age 90, was dispatched to team headquarters in Owings Mills to capture a scene that would play out several more times in the league’s modern era, but never under such clandestine circumstances.

Wrote former Sun editor Ernest Imhoff of the picture Pearson snapped through the snowflakes: “This single photograph made owner Irsay the devil for many Baltimore fans and the hero of Indianapolis.”

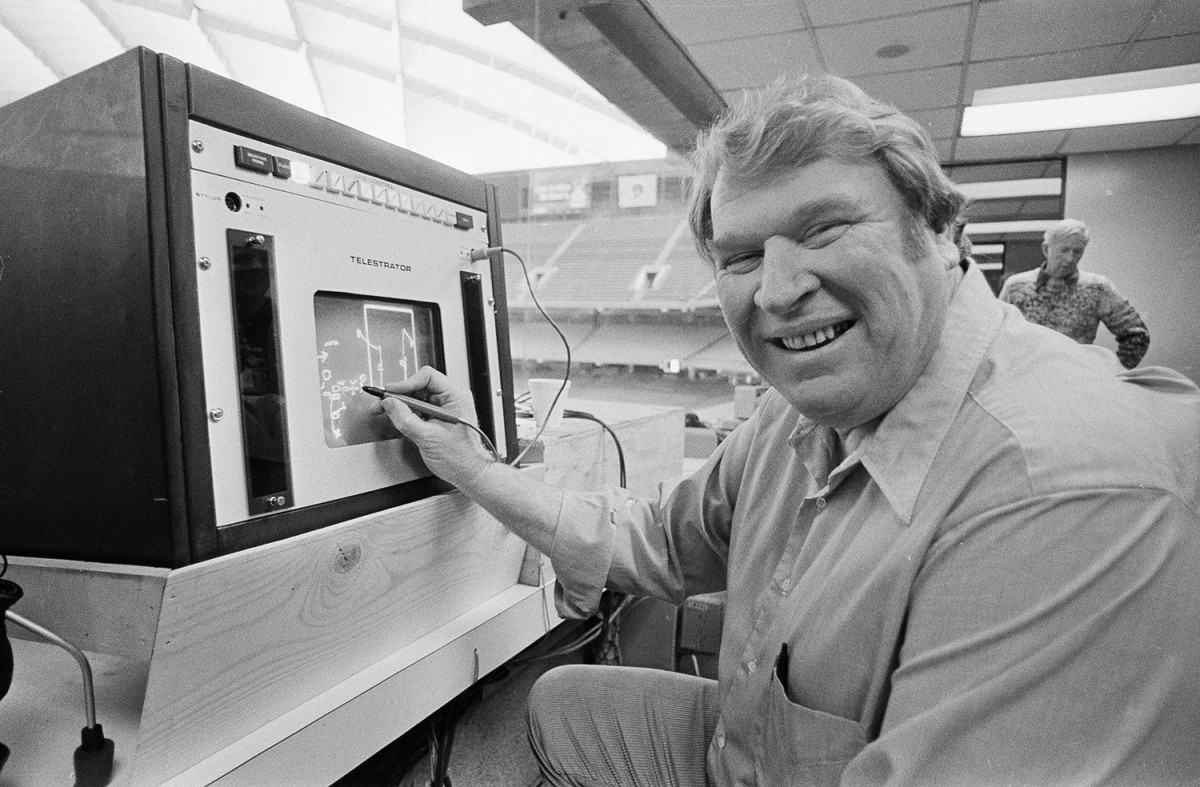

The Madden Cruiser

CBS once rented Dolly Parton’s tour bus for John Madden, as a solution for his famous fear of flying. Soon after that he got his own vehicle, and The Madden Cruiser became an icon in itself. The custom bus debuted in the 1980s and logged 80,000 miles annually, transporting Madden to his broadcast gigs across the country.

It had all the essentials: a bed, a stocked refrigerator and a mobile office where Madden broke down film or got his coaching buddies on the horn. Madden already had plenty on his résumé when he became a broadcaster: During 10 seasons as the head coach of the Oakland Raiders, he won Super Bowl XI and was the youngest coach to reach 100 wins. But he earned the affection of fans nationwide in his second career, as a color commentator for all four major TV networks, with his coach’s eye and endearing Maddenisms—Boom! Doink!

Madden retired from broadcasting in 2009, after three decades, though his name is entrenched in American pop culture through the best-selling EA Sports video game that bears his name. And the Madden Cruiser remains a fond memory: Quirky and wildly popular, just like the man it carried.

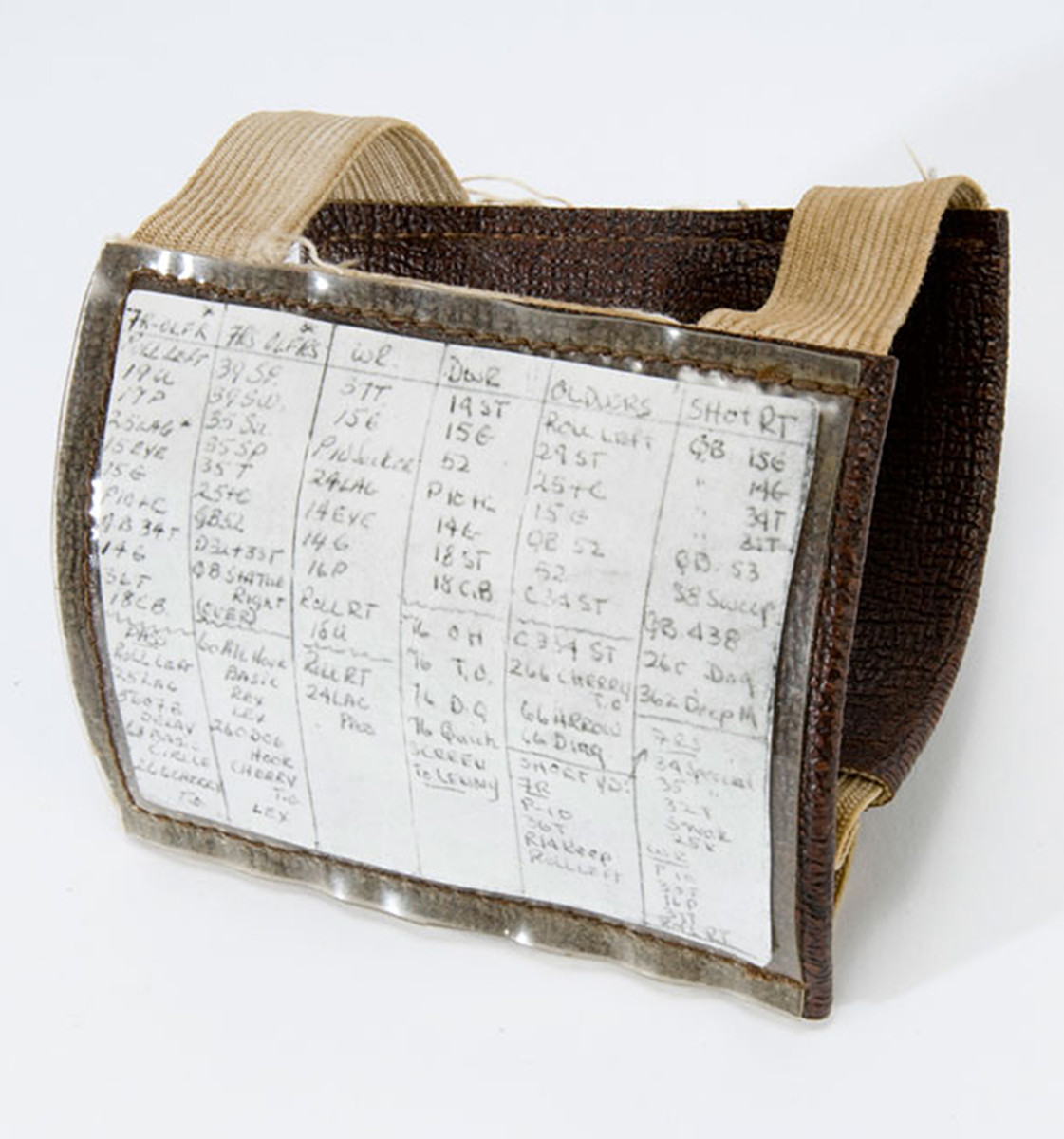

Tom Matte’s Playbook Wristband

Part of Don Shula’s success was adapting to each quarterback he coached—including the running back he was forced to play at quarterback.

Shula’s 1965 Baltimore Colts improbably lost both starting quarterback Johnny Unitas and back-up Gary Cuozzo right before the climax of their season. For the regular-season finale, and the Western Conference playoff, Shula turned to a running back who had never been a signal-caller in the pros: Tom Matte. Scrambling, Shula simplified the offense and gave Matte a makeshift plastic wristband with the Colts’ plays scrawled on a card underneath. Matte would have led his team to the NFL Championship Game that season were it not for a controversial fourth-quarter field goal by the Green Bay Packers—it appeared to sail wide of the upright—that gave Vince Lombardi’s squad the opportunity to win the conference playoff in overtime.

Matte returned to his preferred position of running back for the rest of his 12-year career, but in his brief three-game stint as an NFL quarterback, he turned out to be a trailblazer. The wristband, a novelty when Matte wore it, is commonplace among full-time quarterbacks today.

The White Football

Long before playing under the lights was considered prime time, it was an oddity that called for a most unusual piece of equipment. The Providence Steam Roller’s meeting with the Chicago Cardinals on Nov. 6, 1929, was the first NFL game played at night, and the teams used a white ball in case of foundering floodlights.

The white football—which a local newspaper compared to a large egg seeming apt to crack each time it was passed through the air—actually outlasted the Steam Roller franchise, being used well into the 1950s. It was showcased by Otto Graham and the Cleveland Browns on the evening of Sept. 16, 1950, when they made a roaring entrance into the NFL by stunning the defending champion Philadelphia Eagles; it even snuck onto a few football trading cards of that era.

But there were drawbacks: Players complained that it was slippery and hard to distinguish from white uniforms. By 1956, the white football was extinct in the NFL, rendered needless by high-watt floodlights and TV lighting requirements—a shame, if only for the fact that it could have been a star during the power outage of Super Bowl XLVII.

Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders Uniform

So established are the Dallas Cowboys cheerleaders that even Jerry Jones couldn’t ruin them. Longtime Cowboys fans may remember a four-day offseason spat in June 1989 in which 14 cheerleaders quit when informed of new owner Jones’s plans to trim the cheerleaders’ uniforms and relax policies against fraternizing with team employees and promoting alcohol. The public outcry that ensued forced Jones to back off any changes to ex-general manager Tex Schramm’s brainchild.

In 1972, Schramm, the man who put the star on the Cowboys’ helmets, scrapped the high school boys and girls who cheered games in sweaters and long skirts and pants in favor of a handpicked dance team dressed in high-cut shorts and bare midriffs. They were going for a sexy-but-wholesome aesthetic, hiring young professionals and governing them with strict rules. The uniforms and the rules would remain largely the same, with the rest of the NFL taking note and modeling their cheerleaders after Schramm’s.

The team faced criticism from feminists who noted the most prominent females in pro football were scantily-clad side acts. But America embraced the new look, and the Cowboys cheerleaders became a cultural phenomenon—with their own posters, calendars, Making of . . . shows and even a full-length 1979 made-for-TV movie starring Bert Convy and Lauren (Love Boat) Tewes.

For better or worse, the cheerleading tradition has persevered in the NFL. As of 2019, 26 six teams had official squads—only the Bills, Bears, Browns, Giants, Packers and Steelers did not. In Buffalo, the team suspended operations of the Jills in 2014 after five cheerleaders filed a lawsuit over compensation and what the plaintiffs called degrading treatment. Several other teams, including the Raiders, Texans and Saints, have faced similar suits in recent years. Is the future of cheerleading in doubt? Hard to say—in 2016 the Lions, who hadn’t had official cheerleaders since 1974, added a squad.

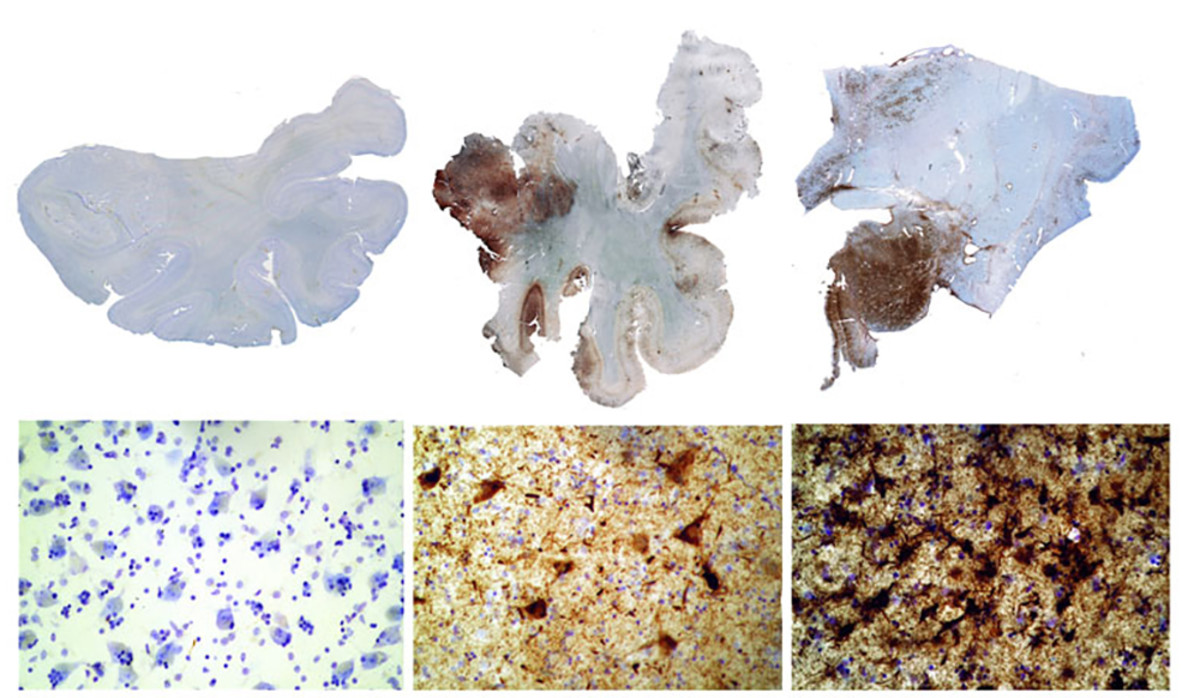

Tau Protein

It’s not something the naked eye can see, and until recently it wasn’t detectable outside an autopsy room. Frankly, few of us know much about it. But the more scientists learn and tell us about the abnormal protein called tau—which can build up to cause Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a deterioration of the brain—the more we realize that although microscopic, it could be one of the most important factors in the future of football.

Scientists at Boston University, notably Dr. Ann McKee, have been at the forefront of research into the relationship between CTE and sports. Their 2009 paper presented evidence of tau’s role in reducing neurological and cognitive function in football players and other athletes who suffer repetitive brain trauma. McKee’s team studied the brains of deceased former athletes who suffered cognitive impairment and discovered significant tau buildup in a majority of them.

Among the deceased players whose brains have been shown to have signs of CTE are Hall of Famers Mike Webster and Junior Seau, and living players including Tony Dorsett have been told they have the condition. CTE has been linked to memory loss, depression, and eventually, progressive dementia. As scientists explore these connections and delve into ways to can identify, treat and, ideally, prevent CTE, the football world has been forced to readjust long-embedded attitudes towards head injuries. We have already seen changes with rules, equipment and medical policies. Will truths about tau tell certain individuals they cannot play the sport? It’s daunting to imagine what a future NFL landscape might look like—it’s not something most of us can visualize, at least not yet.

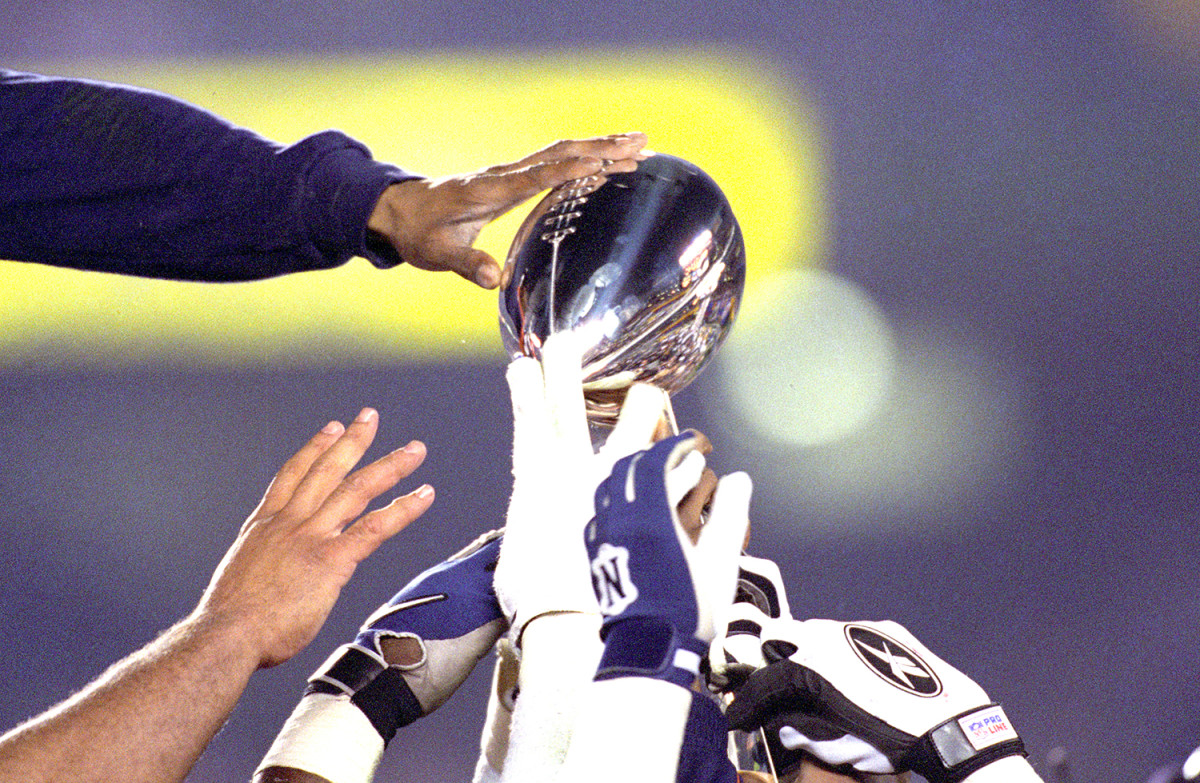

The Super Bowl Ring

Franchises play for and receive the Vince Lombardi Trophy for winning football’s ultimate prize: a Super Bowl title. But since only one trophy is given to each champion, rings are given out to the players, coaches and other staff members. After the 1966 season, Lombardi himself designed the very first one with Jostens, which has created most of the Super Bowl rings. The first had just one diamond, was made of gold and was valued at $750. Inscribed on the inside were three important words to Lombardi’s Packers: harmony, courage and valor.

The NFL pays a small portion toward the creation of 150 rings; the rest of the bill is footed by the club. And sometimes the ring captures more than just abstract notions. After Super Bowl LI, in which the Patriots came back from a 28-3 deficit against Atlanta to win in overtime, the team created rings with 283 diamonds, “to tell the story of the game,” according to a Patriots spokesman Stacy James. That didn’t sit well with Falcons owner Arthur Blank, who confronted Robert Kraft about the bling. “It pissed me off,” Blank said.

The Hupmobile

Ralph Hay was a successful automobile dealer, but his showroom’s place in history far exceeds that of the Hupmobiles he sold. Pro football had existed since 1892 but lacked any real order during its first three decades. A pair of meetings in August and September 1920, in Hay’s showroom in Canton, Ohio, changed that: The American Professional Football Association, renamed the NFL two years later, was organized.

As the story goes, the founding fathers—including Hay, owner of the Canton Bulldogs, and George Halas, representing the Decatur Staleys—sat on the cars’ running boards and drank buckets of beer while devising the league that would become the crown jewel of American sports. Jim Thorpe was elected president, a $100 membership fee was set, and play began within a few weeks. Fourteen teams played that first season, only two of which still exist today: the Staleys, now the Chicago Bears, and the Chicago Cardinals, now in Arizona.

Hay’s Hupmobile showroom has long since been torn down, but at the site in downtown Canton (now the Frank T. Bow Federal Building) you can find a plaque identifying the hallowed ground as the birthplace of the NFL.

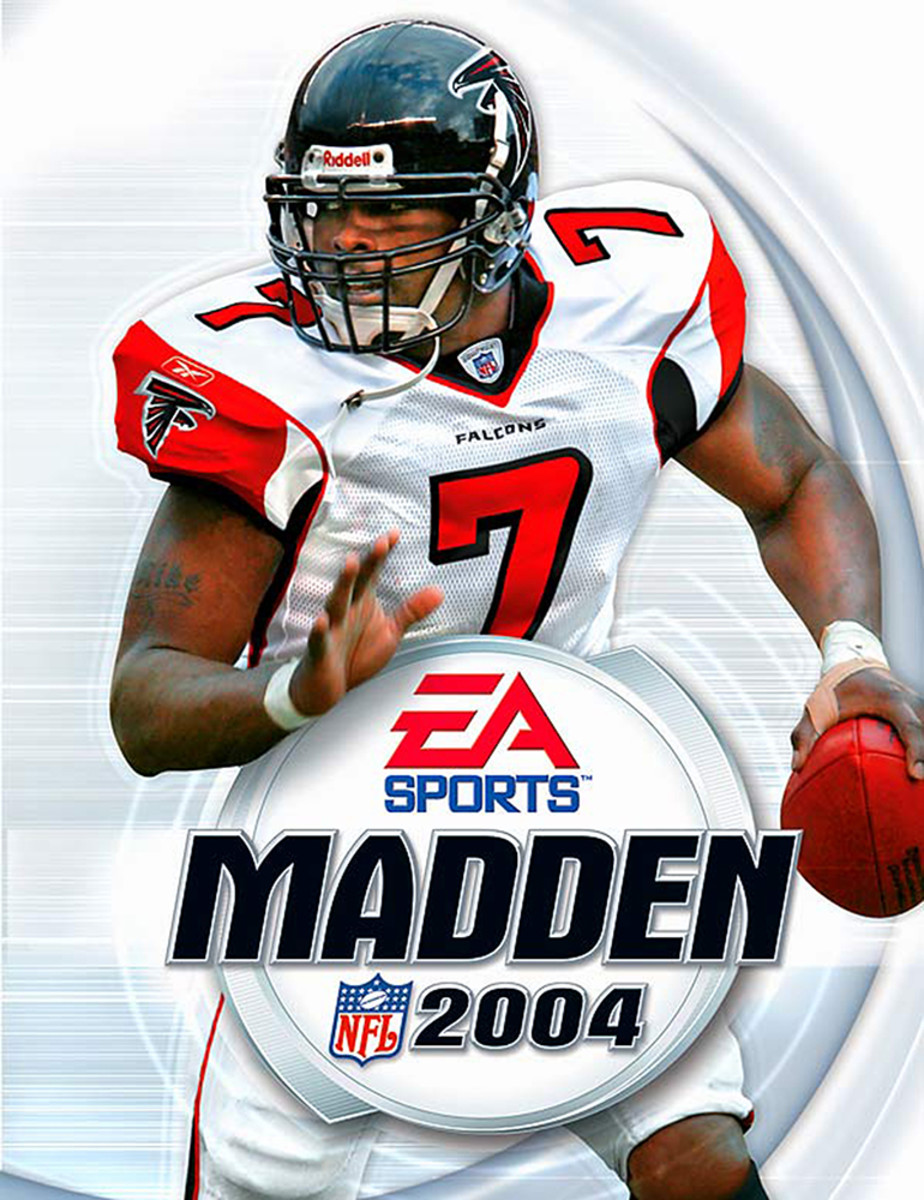

The Madden Video Game

The Madden football franchise, now more than three decades old, almost wasn’t Madden at all.

When the game that would be called Madden was taking shape under EA Sports in the late 1980s for use on the Apple II home computer, EA founder Trip Hawkins saw the former Oakland Raiders coach, broadcaster and robust pitchman as a third choice. The top pick was 49ers quarterback Joe Montana, at the height of his powers at the time and Hawkins’ boyhood idol growing up in Southern California. But Montana already had a deal with another video game maker, Atari. The second choice, Cal football coach Joe Kapp, wanted royalties on the title. So Hawkins went with Madden, and both were in for a crash course; Madden in the power and promise of technology and Hawkins in the game of football.

Madden insisted that if he was putting his name on it the game had to be 11-on-11, a major challenge considering the lack of computing power in late ’80s. As gaming consoles evolved Madden grew more realistic through the ’90s, with NFL teams and logos, and later player names (with the NFLPA’s blessing) becoming part of the game. With realistic playbooks and real-time roster updates, gamers playing current versions can feel like they’re a hoodie away from being the next Bill Belichick.

Through a partnership with the NFL, the franchise eventually brought an intersection of jock culture and gaming, no small feat in the pop-culture climate of the early ’90s. Today, each new version of Madden is unveiled to massive publicity and invariably sells a million copies in its first week on the shelves.

The White Ford Bronco

O.J. Simpson won the 1968 Heisman Trophy, became the first NFL player to rush for more than 2,000 yards in a season (during a 14-game slate in 1973 no less), starred alongside Arnold Palmer in commercials for Hertz, worked on Monday Night Football with Frank Gifford and Howard Cosell and appeared in Roots, The Towering Inferno and the Naked Gun movies. Today he may be the most notorious former athlete in America.

The Hall of Fame running back is now best known for the circumstances surrounding the deaths of his ex-wife, Nicole, and Ronald Goldman in June 1994. Charged with double murder in the case and given the chance to surrender to police on June 17, Simpson instead engaged in a “low-speed chase” with police along the freeways of L.A., in a white Ford Bronco owned and driven by former teammate Al Cowlings—a pursuit that was broadcast live on all three networks and on CNN, interrupting the NBA Finals on NBC. An estimated 95 million views watched the drama unfold. Simpson finally turned himself in later that evening, after reaching his house in Brentwood.

In a criminal case that dragged out for more than a year and that made household names of Johnnie Cochran and Kato Kaelin, introduced America to the Kardashians and brought the phrase “If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit” into the lexicon, Simpson was eventually found not guilty. However, he subsequently lost a wrongful death civil suit brought by the Goldmans and was ordered to pay $33 million. He later served nearly nine years in a Nevada state prison for felony armed robbery and kidnapping, after he tried to steal sports memorabilia at gunpoint that he said belonged to him. The mementos included his Hall of Fame certificate. The Bronco? Simpson’s former agent bought it from Cowlings for $75,000 and kept it in a garage for years, charging the battery every now and then to keep it running. It appeared on a 2017 episode of Pawn Stars and is now on display at the Alcatraz East Crime Museum in Tennessee.

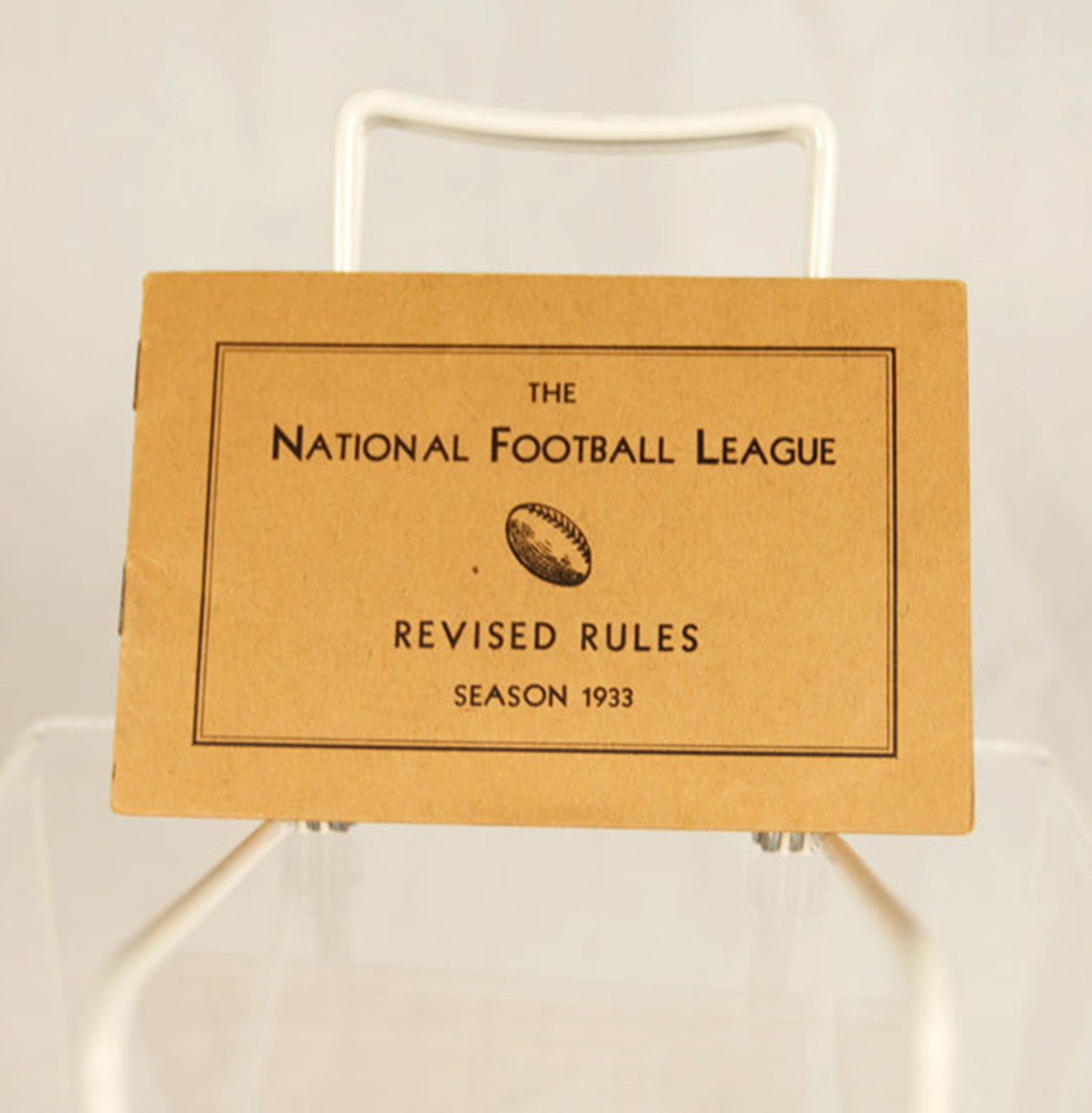

The 1933 Rule Book

The rules have allowed the forward pass in the professional game since 1906. George “Peggy” Parratt of the Massillon (Ohio) Tigers is believed to be the first player to complete a pass in a pro game, with Dan “Bullet” Riley on the receiving end, against Benwood-Moundsville (W.Va.) on Oct. 25 of that year.

But it was hardly ever used because of stiff penalties for incomplete or illegally thrown passes. For instance, the passer had to be five yards behind the line of scrimmage, and the penalty for failing to do so was a turnover, whether the pass was complete or not. A controversy bubbled up in the 1932 championship game between the Chicago Bears and Portsmouth Spartans when Bears fullback Bronko Nagurski faked a run and then threw a touchdown to Red Grange. The Spartans protested that Nagurski wasn’t five yards behind the line of scrimmage. The play stood, and the Bears later won 9–0.

At the league meetings after the season, Spartans coach George “Potsy” Clark asked for a rule change to legalize any pass thrown from behind the line of scrimmage. The move, which would transform football and lead to the aerial show we see today, wasn’t meant to further the pro game, which had adopted the college rules to that point. It was because, Clark argued, “Nagurski would do it anyway!”

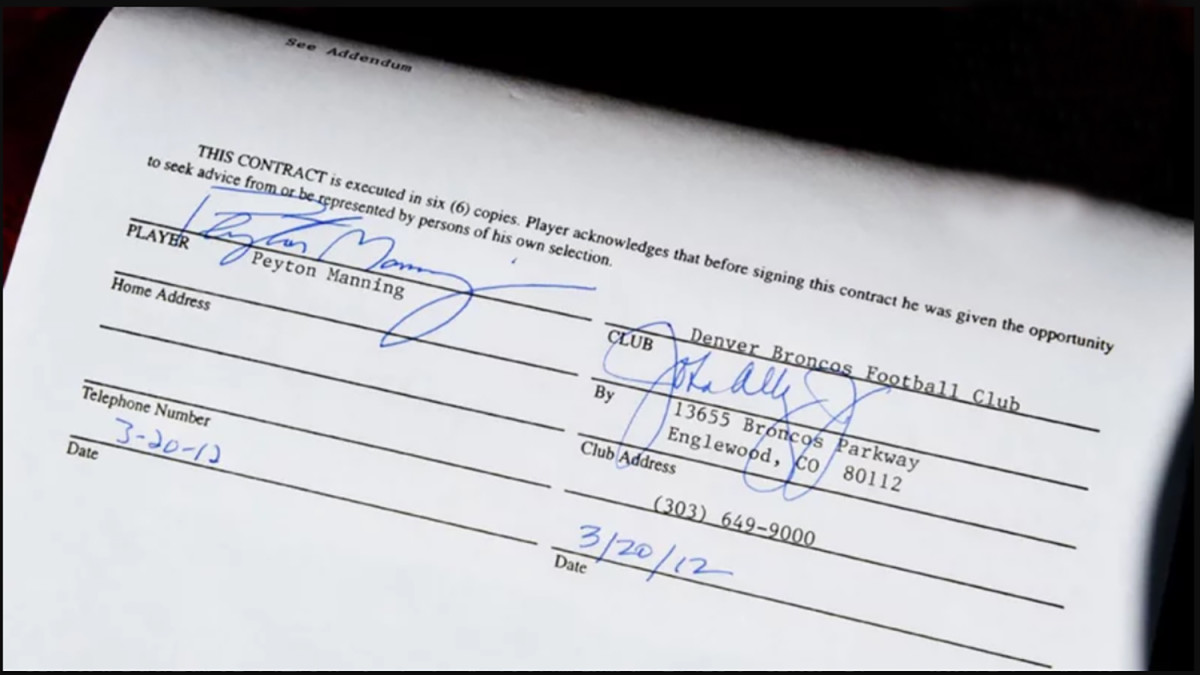

Ryan Leaf’s Colts Jersey

Here’s all you need to know about how inexact the science of drafting can be: In February 2013, the first overall pick in the 1998 draft, Peyton Manning, was playing for his second team in his third Super Bowl at the end of his fifth MVP season, in which he earned a $25 million salary.

The second overall pick from ’98, Ryan Leaf, was in a Montana prison, having flamed out of the NFL after five seasons. He was arrested twice in two days in 2012 and sentenced to five years on felony drug and burglary charges. During the sentencing, Leaf told the judge, “I’m lazy and dishonest and selfish. These were behaviors I had before my addiction kicked in.”

In Leigh Steinberg’s book The Agent: My 40-Year Career Making Deals and Changing the Game, Leaf’s representative revealed that the Washington State QB intentionally skipped his pre-draft meeting with the Colts in order to avoid being taken No. 1, leaving Indy and San Diego fans alike to wonder what might have been had the 1998 draft gone down differently. For one, the No. 16 Colts jersey pictured above would have been awarded to Leaf had Indianapolis called his name first at Madison Square Garden during the 1998 draft. Signed by Leaf, it hangs on the set of the Dan Patrick Show in Connecticut. Manning’s blue No. was 18 retired by the Colts in 2017 and hangs from the rafters in Indianapolis.

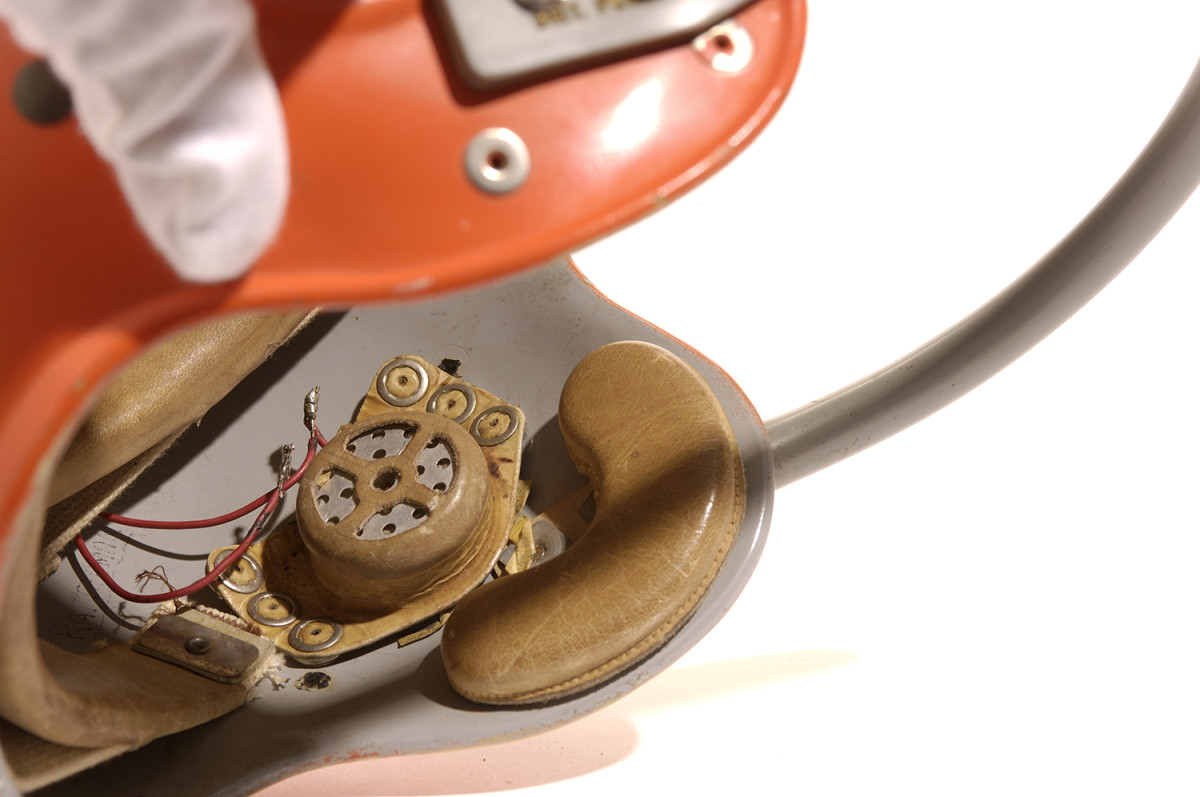

Tom Dempsey’s Boot

They called him Stumpy. Born without a right hand or toes on his right foot, Tom Dempsey had seemingly no future in professional sports. Yet on November 8, 1970, Dempsey kicked a 63-yard field goal—setting an NFL record that endured for 43 years—not in spite of his clubbed foot, but rather because of it.

Dempsey began his kicking career barefoot, simply wrapping athletic tape around the end of his right foot. Sid Gillman signed him to his Chargers taxi squad in 1968, and the coach helped develop a better tool for kicking. Dempsey’s new shoe was a $200 custom leather boot that featured a 1¾-inch leather block at the toe; it resembled (and struck like) a sledgehammer. Fast-forward two years and one team later, to Week 8 in 1970, as Dempsey and the 1-5-1 New Orleans Saints hosted the heavily favored Lions at Tulane Stadium. With the Saints down 17–16 and two seconds remaining, Dempsey took the field for what was considered an impossible attempt. It wasn’t. His 63-yard bullet snuck over the crossbar, winning the game and upping the ante for kickers—the previous record was 56 yards, set in 1953.

Stumpy became an enchanting folk hero for the four-year-old Saints. As for the boot: Though never proven, the NFL believed it created an advantage. In 1977 the “Tom Dempsey Rule” required players with artificial limbs to have footwear that conforms to the shape of a normal kicking shoe.

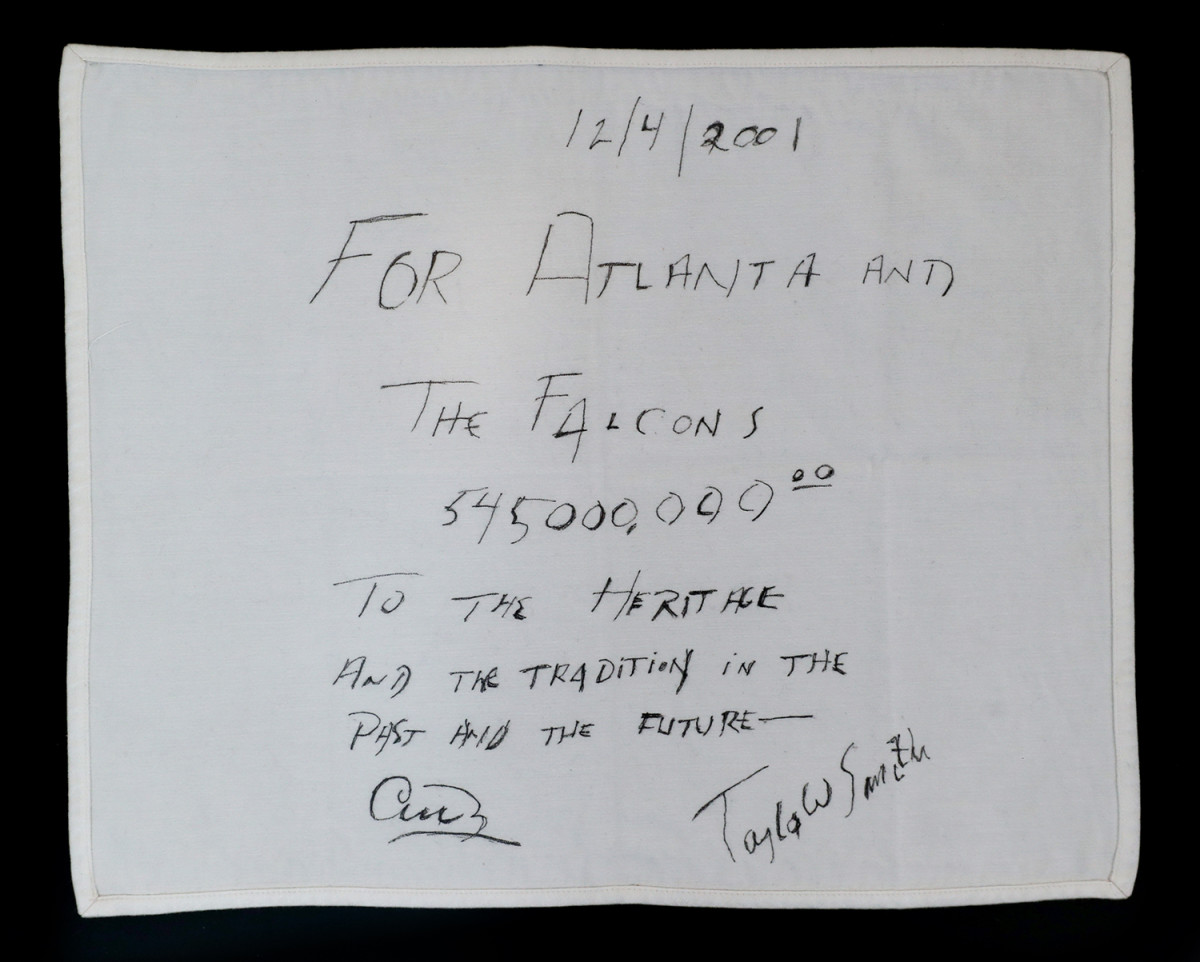

Arthur Blank’s Napkin

Atlanta’s transformation from a city of finicky football fans to fervent supporters, along with the Falcons’ shift from occasional playoff team to regular contender, can be traced to one white dinner napkin. Sound ridiculous? Consider what was written on it. Atlanta joined the NFL in 1965, making the playoffs six times under founding owner Rankin Smith (and later his son, Taylor). But the Falcons never recorded consecutive winning seasons, and the team’s lone Super Bowl appearance was marred by the arrest of safety Eugene Robinson for soliciting a prostitute the night before the game. Fan support was lukewarm.

In 2001, Taylor Smith decided to sell the franchise. Home Depot co-founder Arthur Blank was an eager suitor, and over dinner the men reached an agreement. To consummate the deal, Blank began writing the contract on a napkin. Initially, Smith was skeptical. Is this guy serious? Yet soon enough, both men scribbled their names on the makeshift contract, a $545 million deal. While the Falcons enjoyed immediate success under Blank, they endured a rough patch in the mid-2000s, especially after quarterback Michael Vick pleaded guilty for his role in operating a dog-fighting ring. With an emphasis on drafting homegrown talent and strengthening community ties, the Falcons have emerged as a model franchise, with a gleaming showcase stadium (shared with Blank’s wildly popular soccer team, Atlanta United FC) drawing sell-out crowds. The napkin, if you will, wiped a clean slate.

John Zimmerman’s Bednarik-Gifford Photo

Concern over player safety has become an integral part of the game in recent years, but the sheer brutality of football has undoubtedly fueled its popularity. One of the most famous hits, delivered and received by two future Hall of Famers, occurred on Nov. 20, 1960, at Yankee Stadium. It resonated at the time because the game was broadcast live on national TV; and it resonates today because of the photograph snapped by Sports Illustrated photographer John Zimmerman, which has become one of pro football’s iconic images.

With the Eagles leading the Giants 17-10 late in the game, New York quarterback George Shaw connected with flanker Frank Gifford on a slant. Gifford was leveled by Eagles linebacker Chuck Bednarik with a forearm to the chest. Knocked unconscious, Gifford was rushed to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital and wouldn’t play again for 18 months; the six-time All-Pro was diagnosed with a deep brain concussion at the time, but he learned decades later that what he actually suffered was a spinal concussion. The hit paved the way for Philadelphia to win the East conference: Gifford fumbled on the play, the Eagles recovered to seal the victory, and they won the rematch against the Gifford-less Giants the following week on the way to 1960 NFL title.