There Is Still Chlorine in Michael Phelps’s Soul

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. This year’s WHERE ARE THEY NOW? crop features a Flying Fish and a Captain, jet packs and NFTs, the Commerce Comet and the Say Hey Kid. Come back all week for more.

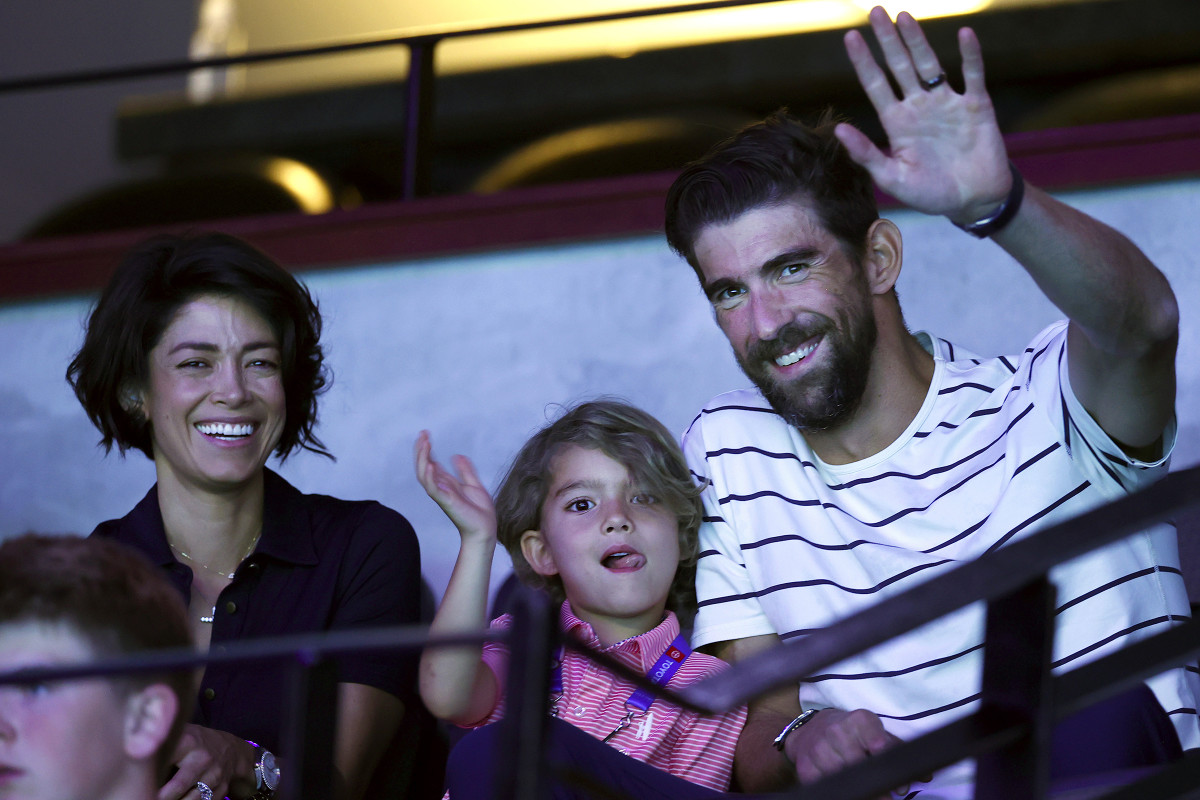

Boomer Phelps wore an NBC media credential around his neck, which certainly made him the youngest accredited person in attendance at the U.S. Olympic Swimming Trials in Omaha last month. His job was “Michael Phelps’s Son,” and the 5-year-old performed it with adorable aplomb. Everyone swooned over his cascading golden hair and sparkling brown eyes, but Boomer really just wanted to hang with dad.

“He won’t go to anyone else all week,” Phelps says, and he’s not complaining. With younger sons Beckett and Maverick not making this trip, this is great one-on-one bonding time.

Sitting in his famous father’s lap, Boomer learned about starts, turns, kicking underwater and other intricacies of the sport that Phelps defined and elevated like no one else in history. They were in The House MP Built; the grandiose idea of a swim meet in a 17,000-seat basketball arena with eight consecutive nights of prime-time NBC coverage would have been laughable without Phelps’s transformative work. But now at age 36, Phelps is on the other side of it—watching from the stands, dry, surveying a realm that seems to be swimming fine on its own.

For the first time since 1996—when Bill Clinton was in his first term, Michael Jordan still had a couple of NBA titles left in him and the internet was still new—there will be an Olympics without Michael Phelps. “It’s weird,” he says. “But hopefully relaxing. I think it will be good to watch it with the whole family. During a big meet I always feel like I’m on high alert, super tense, and this should be more relaxing.”

Perhaps Phelps will be able to relax when he’s in his living room and the competition is on the other side of the globe. But if you get him near the pool for a major competition, all his well-honed swimming instincts re-engage. The Olympic Trials, with all its attendant energy and all the memories of dominance there, was an emotional one.

“For me, just walking onto the pool deck, I felt chills running up my body,” he says. “I almost had to stop and let everything sink in. It was semi-overwhelming, but in a very positive way. I felt the tears start coming up.”

There is chlorine in Phelps’s soul. This was his chosen path through life from pre-adolescence, spanning five Olympic Games, winning a record 28 medals, including a record 23 gold. He had the longest run of success in the hardest of sports to sustain it, and he appears to be in good enough shape to still land on the podium in an Olympic event or two. “This is all I know and all I ever understood,” he says, a statement based in truth but also a dramatic underselling of his development over time.

By his own proud admission, Phelps always has been a “nerd-geek” about swimming. That begins with a photographic memory of his own races. Bob Bowman, his lifetime coach and de facto father figure, recalls watching some races recently with his greatest pupil and being struck by the detail of his recollection. Reviewing the 200-meter individual medley from Rio de Janeiro in 2016, Phelps pointed out, “In about five yards, I’m going to take a breath to my left to see where Thiago [Pereira of Brazil] is.” Sure enough, that’s what he did.

But Phelps’s immersion extended beyond himself. Despite a series of unprecedented performances over 16 years, he remained intensely interested in what was going on around him. Even at the height of his prowess he watched all the races—and he digested them, checking times and strokes and tempos. If a random swimmer had a standout performance at a meet where Phelps was competing, the GOAT almost certainly noticed.

That hasn’t changed. He says he wrote down all his predictions for Olympic Trials—times and places—and there was even a rumor of Phelps being in a super-exclusive pick ’em contest with a few other ex-swimmers. He watched what happened in Omaha, and he had some thoughts.

“I’m surprised they’re not faster in some events,” he says. “These next few weeks for these Olympians will be a true test. We’re going to have our hands full with swimmers from a lot of countries. …The one thing that frustrates me the most is seeing a swimmer almost fall apart at the end of a race, kind of have that piano on their back. Those last finishing 10 meters are so important—that’s the race.”

Phelps specifically was referring to 22-year-old rising star Michael Andrew, the American heir apparent to Phelps in the 200 IM while also making the American Olympic team in two other events. The 6' 6" Andrew is immensely talented and has been on the radar since controversially turning pro at age 14, but his training has always been unconventional and left him open to critique. Enter the man who won every Olympic 200 IM from 2004 to ’16: Phelps referred to Andrew as “someone who has an amazing 75% of a race” but cannot finish well enough to seriously threaten Ryan Lochte’s 10-year-old world record in that event.

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

Phelps made similar comments regarding Andrew on-air while sitting in between play-by-play man Mike Tirico and longtime analyst Rowdy Gaines during the Trials. That analysis arched a few eyebrows in an exceedingly diplomatic sport, but also made clear a potential future role for Phelps: the Johnny Miller of swim commentary, with a lot more hardware to back up his candid assessments. “I think he’d be a great analyst,” says Bowman. “He just sees it with different eyes.”

For now, Phelps has plenty of other things to keep him occupied. He says he has more sponsors now than at any point in his life, which dovetails with his increasingly articulate and passionate views on things other than flip turns and closing speed. “We’re still hammering on this mental health,” he says.

Phelps’s voice—his vulnerability and honesty in the wake of serious public pratfalls—did as much as anyone’s in the world to blaze a trail for athletes to acknowledge their mental health issues. The dialog he had a role starting six years ago has expanded, with his encouragement and involvement. “I’m so proud of him for that,” Bowman says. “He struggled through a large part of his career with those things. I’m sad to say I couldn’t help him. I wasn’t equipped. Everyone saw him as a machine, and physically he was a machine—but machines have insides.”

Phelps was moved by tennis star Naomi Osaka’s recent comments on her mental health, and he’s made himself available as a resource for many in the swimming community to discuss their struggles. There is more to come: Phelps is working on a book with Karen Crouse of The New York Times that he says goes into greater detail about his struggles outside the pool.

“I really just feel like there’s hope that this stigma is going away, the wall is being broken down, we’re finally accepting it,” Phelps says. “We should be able to. What Naomi did on that stage was very powerful and very vulnerable. It’s always going to be such a battle.”

Phelps will help wage the battle while being the kind of involved and present father he didn’t have as a kid. He’s worked over the years at mending his relationship with Fred Phelps while also learning from his dad’s mistakes. He takes Boomer (who says he wants to be a pro golfer) to the driving range frequently. And, yes, he’ll jump in the pool with all three boys and wife Nicole at his Scottsdale home. (The extremely early scouting report is that 2-year-old Maverick might be the most naturally Phelpsian in the water.)

“I’m the grandpa who lets them do what they want if it’s not going to kill them, and he’s the ‘No’ man,” Bowman says with a laugh. “But he’s really good with them. It is great to experience this side of him.”

Father, budding TV analyst, author, mental health advocate—Michael Phelps keeps winning, even on dry land.

• The Charmed Season: Revisiting Derek Jeter’s Origin Story

• How Ricky Williams Found Himself in the Planets and the Stars

• We Could Sure Use Dick Cavett Right Now