'This Would Be a Great Way to Go Out': Behind the Scenes of Pacquiao’s Win Over Thurman

LAS VEGAS — Manny Pacquiao entered Dressing Room 1 at MGM’s Grand Garden Arena shortly after 6 p.m. on Saturday. He was flanked by his entourage, his wife, his mother and, naturally, Miss Universe. He wore a white sweatshirt, black pants and black sneakers, and his outfit featured so many corporate logos he resembled a human billboard.

As the room swelled with five people, then 15, then something closer to 50, the obvious question lingered, same as it has for years now. For the 40-year-old boxer, the sport’s fighter of the decade a full decade ago, would this be The End?

Pacquiao’s longtime trainer, Freddie Roach, waited in a blue chair. He said his conversation with his fighter earlier that morning had centered on their strategy to fight Keith Thurman. They discussed feinting, moving in and out, utilizing the footwork that Pacquiao long ago perfected. But mostly, Roach wanted Pacquiao to punish Thurman’s midsection, then come over the top with a right hand. “He knows what he has to do,” Roach said in that chair, his eyes staring off into the distance, resolute.

“If he does what he’s supposed to, he will win by knockout,” Roach said. “(Thurman’s) body is very weak.”

The television in the dressing room showed Thurman and his crew headed toward the arena, their eyes closed, perhaps in meditation. Pacquiao’s workout czar Justin Fortune pointed at the scene and laughed.

If this was The End, Pacquiao and his team and acolytes would take a relaxed approach. He held group Bible study in the morning and played with his youngest son before leaving for the arena.

At 6:20, he asked for water, which sent several members of Team Pacquiao scrambling for Fiji bottles. At 6:25, he called for a chair, and one appeared magically beneath him. At 6:45, he bounced and stretched and paced, eyeing a potential future opponent in Errol Spence Jr. on the television. At 6:50, he retreated to the bathroom, hiding from the crowd.

The assembled discussed the fight in hushed terms as the bout drew closer. Was Pacquiao the boxer who dropped a controversial decision to Jeff Horn in 2017? Or the one who stopped Lucas Matthysse and manhandled Adrien Broner in the two fights since then?

When Pacquiao took the Thurman fight, oddsmakers made him the underdog. But in the months since, the wagers moved in his direction, making him the slight favorite. This likely owed to Thurman’s own career evolution since ’17, after he topped welterweight champions Shawn Porter and Danny Garcia in back-to-back bouts, then suffered a deep bone bruise in his left hand and injured his right elbow, forcing an almost-two-year layoff that ended with a meh win by decision over Josesito Lopez.

“Why do they call him One Time?” Roach asked inside the dressing room, noting Thurman’s nickname. “Because of that one time he won a world title?”

Still, Thurman promised to retire Pacquiao, the same way that Pacquiao effectively ended the careers of Oscar De La Hoya, Ricky Hatton, Tim Bradley and Matthysse. No one believed that in the dressing room. Not even Miss Universe.

At 7:05, Pacquiao dressed in a small room off to the side. He tugged on white shoes with blue laces that featured red stars and stitching that read “Jesus is the name of the Lord.” At 7:10, he prayed with his mom. At 7:15, referee Kenny Bayless relayed to Pacquiao the usual pre-fight instructions, but he delivered them with such fervor it felt more like a sermon.

“You doing alright?” he asked Pacquiao at the end.

“Doing really good,” Fortune answered. Pacquiao just shrugged.

So this is what The End might have looked like, the scene similar to so many of the 70 career fights that came before. Pacquiao wrapped his own hands. Officials tried to clear the entourage, unsuccessfully, then tried again and again while no one moved. Someone grabbed his gloves from a white envelope marked “PacMan 1” and helped him fashion them over his fists. He worked the mitts with Roach while the Fox cameras rolled. His punches landed with snaps and thuds that echoed down the hallway. He didn’t look old. He looked sharp, ready. They walked through one key sequence over and over at half speed: a right-left-right hook combination, with the last right thrown over the top. “That’s it,” Roach said. “Beautiful.”

“All we gotta do is win now,” his manager Sean Gibbons said.

So there went Manny Pacquiao, out of a dressing room and down toward a boxing ring, for the 71st time. Eye of the Tiger blasted from the arena’s speakers. The pro-Pacquiao crowd unleashed roar after roar, chanting his name, while Miss Universe waved the Filipino flag.

The bell sounded for Round 1. Both men came out swinging. It didn’t take long before Pacquiao put to effective use the sequence he had repeated only 45 minutes earlier. While walking toward Thurman, he continued to throw punches, then he came over the top with the right. Thurman toppled backward onto the canvas. “We worked on that the whole training camp,” Roach said later. “I knew it would work.”

Thurman proved a more-than-capable opponent. That shouldn’t be surprising. He entered the ring 10 years younger than Pacquiao and with no losses on his résumé. Still, he fell behind early, as Pacquaio went after his ribs, landing stinging lefts, staking a large lead.

By Round 6, Thurman was bleeding from his nose and his face featured bruises near both eyes. He started to take some rounds around then. But Pacquiao did not look old. He looked springy and powerful and even when he began to tire later on, he still continued to hunt his much younger prey.

By Round 10, Thurman had almost closed the gap between them. But a combination from Pacquiao stunned him, so much so that had Pacquiao noticed Thurman wobble, he might have finished him right there. Instead, he didn’t see it, and he paused, ever so slightly, just long enough for Thurman to recover and backpedal away.

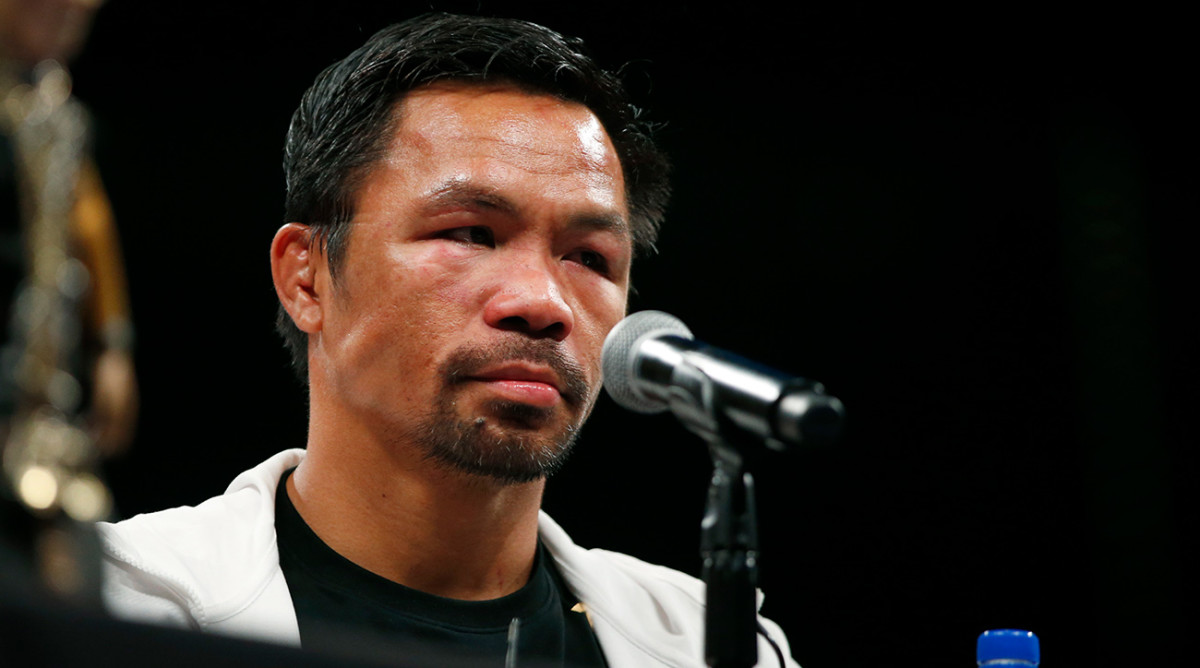

The final bell sounded soon after, and the men’s faces told the story of what had happened in the ring. Pacquiao’s had been touched up. He sported black bruises underneath both eyes. Thurman had inflicted some damage, owing to both his youth and skill. But he wore on his face the outcome, looking like a man who had been beaten up. And, well, he had.

Pacquiao climbed the ropes in each corner and threw both arms skyward. He blew kisses to the fans. They would boo the split decision delivered by the judges, with two favoring Pacquiao by a score of 115-112 and one inexplicably gifting the fight to Thurman, 114-113.

At 10:11 p.m., Team Pacquiao started to fill Dressing Room 1 all over again, only this time the vibe had changed. They cheered every single person who walked in, crowding near the entrance, cell phones held high to capture Pacquiao’s arrival. The screams that went up when he entered caused one woman to cover her son’s ears.

Pacquiao appeared both tired and worn down and, at that moment, for the first time all night, he looked his age. It was like he had been put through a real-time FaceApp in that ring. He praised Thurman and his skill level and appraised this bout as one of the top fights of his career. The assembled started to look forward, to the future, to a Spence bout, or a fight with Terence Crawford, or—God help us all—a rematch against Floyd Mayweather Jr., should Pacquiao be able to coax him out of retirement. Mayweather had climbed into the ring before the decision was announced Saturday and his presence there didn’t seem like a coincidence.

At the press conference, Thurman said that he saw “everything that Pacquiao has always been” on Saturday and that the Filipino champion “has a lot of that still within in.” On one hand, it seemed fair to wonder if this career resurgence might continue—and for how long. Perhaps Pacquiao will try and fight until age 50, like Bernard Hopkins did, or long enough at least to make a run at becoming the Filipino president.

And yet, an alternate scenario presented itself late Saturday, and the whole notion would have seemed unthinkable in recent years. Perhaps because the 40-year-old fighter summoned the Pacquiao of old, selling out Grand Garden Arena, dipping and darting and landing combinations, while the crowd rose to its feet and thundered … perhaps by summoning the exact kind of performance that marked his rise to superstardom … perhaps because of all that he had arrived at the place everyone expected but not in the way most had thought. “This would be a great way to go out,” Roach said afterward in the dressing room. “This was one of our best fights. There’s nothing left to prove.” He paused, as if considering the gravity in that statement. “I don’t know,” he said. “We’ll see what Manny says.”

As Saturday night gave way to Sunday morning, Pacquiao and over 100 of his supporters retreated upstairs, to the top floor of the MGM and his house-sized hotel suite. He sat at a large banquet table, his eyes closed, clearly in pain. Longtime observers said he last sustained this type of punishment against Antonio Margarito, a much larger fighter, in a dominant but scarring victory at super welterweight in 2010.

Gibbons said Pacquiao’s eyes were bothering him, from the combination of Thurman’s punches and Vaseline that had seeped inside. The champion rose from his seat and shuffled down the hallway, requiring the help of two members of his entourage to guide him with his eyes clamped shut. At one point, he bumped into a staircase, and he continued to wipe at his eyes with a towel.

As Gibbons watched this scene, a rough end to an impeccable performance, he saw the best finale in the Mayweather rematch, saying that a Pacquiao victory would “put an exclamation point” on one of the all-time careers in boxing history. It was 12:48 a.m.

Thus began another dilemma, one familiar to all boxers at The End. Did Pacquiao really need to absorb this price, at 40? Would his End be the same sad story that happens to so many boxers who hang on for too long because they need the money or can’t force themselves to quit? It sure seemed that way after the Horn fight. But Saturday felt like something else.

The Perfect Ending.

Should he choose it.