Terence Crawford Stakes Claim As the Best Boxer of His Era With Win Over Errol Spence

LAS VEGAS — Roughly 28 hours before their career- and sport-defining clash, Terence “Bud” Crawford and Errol “The Big Fish” Spence Jr. walked into an empty T-Mobile Arena from opposite sides, through lit tunnels, toward the clearest of clarity with their futures. Crawford’s entourage was so large it resembled a football team and hid him somewhere in the middle of a few dozen bodies. Spence’s group was smaller and leaner, but no less ready or intense.

Boxing champions like Roy Jones Jr., Evander Holyfield, Antonio Tarver and Riddick Bowe milled backstage. Their presence alone, for a weigh-in that was no more than ceremonial in nature, made for TV—the real versions took place Friday morning at the MGM Grand—signaled the immense stakes. Tommy “The Hitman” Hearns was in the house, hoping, along with thousands of others who descended on Las Vegas during an epic heatwave, for another welterweight classic. The old-school, vintage kinds he long ago engaged in.

Crawford’s head trainer, Brian “BoMac” McIntyre, banged the ring apron like a drum with both hands. Two men carried four belts and the white, satin-like bags they would soon be gently placed in. Once inside, all four would stay there until both undefeated champions and their teams carried them into the ring late Saturday.

As Mike Tyson strolled onstage, before a scuffle broke out between two boxers in a nearby hallway, everyone joined in a collective hush. The fighter's facial expressions said more than anything they had said for months. They were serious, intense, funeral-adjacent or super-fight ready. You could almost feel the energy emanating from those expressions. It came across, more or less, like it’s … about … to go … down.

Onstage, the boxers ran through the usual machinations: undress, step on scale, flex, pose; endured the flashing lights, the probing spotlights, a packed crowd and, for Crawford, heavy boos; then stood inches apart, primed, ready, chomping. But then something unusual happened, something I’ve never seen in the 15 years I’ve covered fights like this one. (And, in hindsight, there weren’t any other fights like this one.)

Spence’s team may have been wearing “Smoking On Bud” T-shirts. And Crawford’s confidants may have pulled on their own merch that read, “NEBRASKA/FIST BATTERED/FISH FRY.” Both boxers wore black Air Force 1 sneakers on their feet. Both chose those shoes intentionally, as a nod to a street code of sorts. Crawford spied Spence’s kicks and laughed. But when it came time for the menace, for two boxers who have traded insults and appraisals of their superiority for months now, to talk trash and clench teeth and inch closer, nothing of the sort actually happened.

Instead, Spence leaned in close and whispered in his opponent’s ear. Showtime’s cameras caught the exchange. Spence said, “Thank you for making this fight happen.”

Crawford smiled. Once more, for those who don’t understand how rare that is. He … Totally … Willingly… Smiled.

“Thank you,” Crawford responded. “We can thank each other.”

The friendship vibes didn’t last long, though. Crawford stalked into T-Mobile Arena as early as he possibly could Saturday afternoon. It was 5 p.m. here and still hot as all hell. Now, boxers but especially the best boxers, the elite boxers, the champions among champions, almost never arrive on time for a bout of such magnitude with three others to be held before they can even walk. I’ve never seen someone arrive exactly on time until Crawford did. And this, from a fighter who routinely nods off when reviewing his own fights on his grandmother’s couch in Omaha, Neb.

Stephen Espinoza, the president of Showtime Sports, saw Crawford heading in. Espinoza has worked in boxing for decades, with Oscar De La Hoya and Golden Boy Promotions before Showtime. But as the undercard plowed forward, back inside the VIP reception, he said he had never seen a fighter—not De La Hoya, not Floyd Mayweather Jr., not Manny Pacquiao or anyone else—make such an emphatic entrance without saying a word.

At the weigh-in, BoMac wore a T-shirt with Ice Cube’s likeness printed on the front. Perhaps he hoped that in 24 hours Crawford would embody Cube’s most famous anthem: “It Was a Good Day.” Which is exactly what their team expected. Crawford’s close friend and camp member Bernard Davis said he had never seen the welterweight this primed, and he predicted a 10th-round knockout. Friends, of course, have said similar stuff before every fight ever held. But that was the vibe that Crawford oozed all week. Locked in fails to capture the full intensity.

While Crawford stalked inside, wearing a gray tracksuit that read “Even Big Fish Get Caught” on the back, the VIP reception unspooled inside a banquet room on the bottom floor of T-Mobile during the pay-per-view undercard. Star-studded doesn’t begin to cover it. They came, Tracy Morgan and Chance the Rapper and Andre 3000 and Chris Brown, along with Pacquiao and Mayweather and Ryan Clark and Stedman Graham and Damian Lillard. They came, like everyone else lucky enough to snag a ticket, for the show.

It wasn’t hyperbole to describe Saturday’s main event as the closest thing boxing has (this year, anyway) to a Super Bowl. Crawford’s family walked down a corridor with only two hours of time and nerves and anticipation left to whittle. His grandmother was wheeled alongside his mom, Miss Debra. As they walked, one member of the group said they had spied Mike Tyson—and someone else added that Bud was about to go full Iron Mike.

Spence entered the ring two years younger, one inch taller and with a five-inch advantage in reach. Crawford had logged more career rounds and beaten more world champions, albeit in more fights. Between them, they held 67 wins and 52 knockouts. Rarer still.

Both eyed the first “undisputed” title—meaning one boxer holds all of the four major belts simultaneously—in the storied welterweight division. Both wanted to join the welterweight classics lexicon. Think: Leonard-Hearns (1981), Whitaker-De La Hoya (’97), or De La Hoya-Trinidad (’99), Pacquiao-Cotto (’09).

Crawford even targeted an undisputed crown in a second division, a first for a male fighter in the sport’s history. He seized his first at junior welterweight in 2017, which prompted the move up and led to a career stall that wasn’t his fault at all. He could land any punch a boxer can throw, from both stances, but not the opponents he most wanted to bludgeon. Like Spence.

“This is one of the best fights to be made this century, with both guys being undefeated and with everything Terence accomplished,” McIntyre said. “It means a lot, and I’m expecting a lot of fireworks.”

BoMac was right. Dead right. Gloriously right. Mark-this-one-down-in-the-annals right. Boxing-ain’t-dead right. Saturday night was electric, but especially Crawford, a champion for years and years who never received the full due he long ago earned. He’s charming and dynamic once you know him, but not exactly media friendly, which didn’t help but won’t matter even a little now.

Crawford was special Saturday. Legendary. Iconic. The majority of the fireworks came from him. He triumphed in a dominant performance—a ninth-round TKO to improve to 40–0—that was almost painful just to watch, for the bludgeoning he clinically delivered. He won with right hooks and straight lefts, won by fighting from orthodox and southpaw stances, won despite absorbing a high number of body shots and stiff jabs. He triumphed with a knockout in Round 9, with what seemed like half of Omaha in the stands and in the ring, with a sold-out T-Mobile Arena rising and roaring and partying at a fight that ranks among the best bouts of this century. (Which, before we wholesale buy into typical boxing hyperbole, isn’t yet a quarter old. But still … this night and that fight, they’re boxing at its absolute best.)

Spence, after losing a coin flip—the actual act performed, naturally, by Tyson, who flipped and watched the coin fall to the floor and under a chair—walked toward the ring first. He wore a red ball cap atop his head and a fairly neutral expression on his face. Apple watches began to ping with “loud environment” alerts.

Crawford came out next, with a special guest, Eminem, who rapped the night’s most fitting anthem, his own, “Lose Yourself.” But there was more. Bud wore a diamond-studded chain around his neck and draped a fishnet—like a real, full-size fishnet—over his left shoulder. His expression was gloom-and-doom, as if was headed toward his shift as an undertaker, rather than the most important night of his life.

Anticipation built. Intensity heightened. Those minutes remain, regardless of how you view boxing and its supposed health, the most electric in sports. Finally, after six years of stalled negotiations, after a fateful phone call between both fighters sealed the fight everyone with a pulse desperately wanted to see, after the squabbles and debates and the hype train barreling down to Vegas, Spence and Crawford bounced inside the same ring.

The opening bell sounded, gloriously, at 8:33 p.m. local time. The vast majority of the crowd had already sat down, not wanting to miss a second of the bout. That’s also rare, even for the big ones. Crawford wore black trunks with a fish net—a fish net!—stitched onto them. Spence donned black-and-white trunks, with a red belt line and various stripes.

Spence dominated Round 1, which is typically a feel-out affair anyway. But Spence has long demonstrated a thudding jab, and he announced just how thudding early.

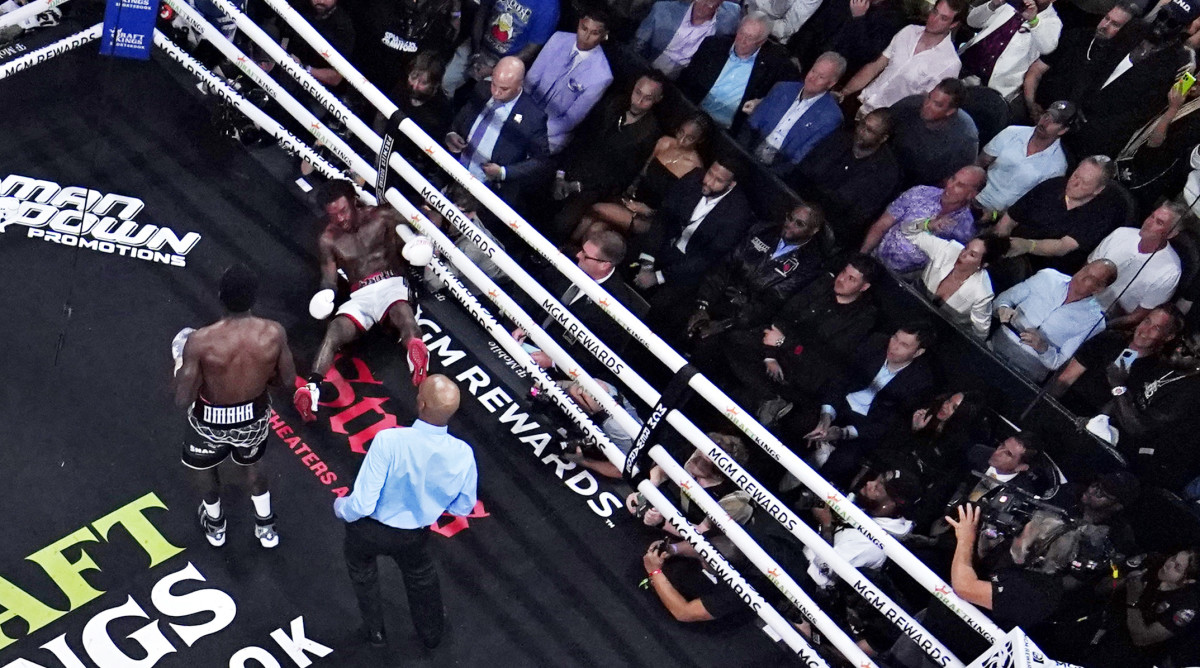

The fight turned the next round, though. Spence continued to hunt for jabs and body shots, in both cases, with precision. But then! Spence lunged too far at Crawford, lost his balance and Crawford, as he always does, pounced. He tried a left first, and Spence partially blocked it. Then Crawford sailed a right into Spence’s face—and down The Big Fish went, caught in the net Team Crawford had predicted.

Spence would later say that his timing was off. He alluded to issues making the 147-pound weight limit, but Crawford had those, too, and Spence did his best to minimize the impact of whatever energy all the weight loss and weight maintenance drained. He said he felt Crawford’s true power in those early rounds, but that all the swelling and bruising on his face never impacted his vision. “I couldn’t kick it up a notch,” Spence said.

Still, A bout that had been billed as a callback to the 1980s welterweight heyday had not been exaggerated, after all.

Spence came right back, undeterred by his brief meeting with the canvas. He continued to land jabs, continued to pound the body. He trapped Crawford in a corner and unleashed a flurry that drew the crowd to its feet. The camera flashed to Mayweather in the stands before Round 4, and Crawford, whether inspired by Money or money, compiled his most complete round of the bout. Spence’s face was starting to redden and bruise. He looked like he was beginning to tire, too.

After the fifth started, Crawford appeared to be timing Spence better and more. And yet, Spence came back from that, too. He started targeting Crawford’s midsection exclusively. This was smart, because he already looked tired, and his best chance at that point was to force Crawford into the same feeling. The sixth was the first close round and, halfway through a night that portended greatness, the bout was so close that, if not for the knockdown, it likely would have been tied.

The fight turned, for good, it seemed, in Round 7. Crawford came out intent to dictate the action. Dictate, he did. When Spence trapped him in a corner, after landing a stiff straight left to the face, Crawford responded with a sharp right hook. Spence crumpled to the canvas. When Spence rose, Crawford stalked back toward him, hoping to finish the night early. He threw a series of that same right hook, each with more force than the one before. Didn’t matter. There it came, another right bludgeoning Spence’s cheek, perhaps breaking his orbital bone, like he had done to his two previous opponents (Kell Brook, Yordenis Ugás).

With a 10–7 round booked and three knockdowns collected, Crawford took absolute and total control. Spence should be credited for what he did anyway, which was continue to come forward, keep throwing, keep trying, no matter how many blows he absorbed or how much they hurt.

The fisherman had netted his big catch, but Spence fought to the very, very end. He even did an in-ring interview, where he looked concussed, his face battered and bruised, his words slurred. Warrior stuff. Or too much warrior stuff. A trip to the hospital seemed likely. His right eye was nearly closed. Still, he said he wants a rematch—and there’s an automatic rematch clause involved on both sides here. But Spence also said he wants the rematch at junior middleweight, the next division up, then later demurred when asked if he would accept the rematch at welterweight. But Crawford later said he was eyeing a division move up of his own, hoping to face Jermell Charlo, another undisputed champion. Consider that history, if Charlo can get by Canelo Álvarez in September.

Crawford had already proven the naysayers wrong—and, to be clear, there were not nearly as many as his camp continuously claimed. He was favored, after all. They said he couldn’t back Spence up. He did. They said he didn’t possess enough power to hurt Spence. He did. They said his chin wouldn’t hold up against a taller, longer, stronger fighter.

It held up better than Spence’s chin did. Crawford was out-landed by his taller/longer/stronger opponent, and the margin was wide: a full 90 additional punches for Spence. But these numbers are what mattered. He threw 163 power shots —and he landed 98 of them. A 60% rate on power punches is almost unheard of, let alone in a blockbuster fight, let alone against an opponent like Spence, who had never before been knocked down. Not once.

“I may never get over it,” said Derrick James, Spence’s trainer, later Saturday night.

Eminem must have been proud. Crawford won his own battle, on an international stage. Drake’s “SICKO MODE” verse blasted over the stadium speakers: “Out like a light, like a light.”

Crawford thought back to his journey, all the naysayers (a count he perpetually exaggerates!), all the victories, all the work. He thought back to different tactics his team deployed for training this time, like starting it early and setting up in Vegas for a pre-fight camp.

His relatives climbed inside the ring, mom clad in a gold jumpsuit, jumping all over the place. The ring all but sagged from the number of bodies crammed inside. It seemed like all of Omaha managed to talk their way in.

Like Mayweather used to on these exact stages, Crawford thanked God. He said that victory mattered because of who he had taken four belts from. Meaning Spence and his Premier Boxing Champions backers. Crawford isn’t wrong there. Spence’s management trotted him all over the welterweight division, everywhere, that is, but toward Crawford until there was no one else to fight. In the ring afterward, Crawford said he had been “blackballed.” That’s probably a bit of a stretch, but it’s also in the right neighborhood. Either way, any obstacles still in Crawford’s path vanished—and for good.

“Man, I’m an overachiever,” he said. “Nobody believed me.”

He did—one, Terence “Bud” Crawford—and that’s what mattered. Just the little punk—his words—from Omaha who saw far beyond his state and far beyond what most expected from him in his sport. His in-ring interview continued, and the emotional tsunami of the moment hit him harder than Spence ever had all night. “I have so many emotions I could cry right now,” he said.

Later, Crawford would say the bout was “never easy.” When a reporter asked him to rank himself on the all-time greats list, he answered, “I’m up there.” And he took several unnecessary shots at journalists—his career stall wasn’t due to writers, who don’t possess a fraction of the power he’s ascribing to them—but to boxing, as a sport, and where it is now, besieged by promotional squabbles and match-ups like this that rarely come to be. But he ended on a funny one, telling the small audience that those who considered him too small might now want to think of him as too strong instead.

This, all of it, started with the on-time arrival, with the walk-in that was more stalk-in, with the face that told observers something would happen—and that something, something special, would happen, soon. Only Crawford knew that everyone else was wrong. Sure, more felt that he could beat Spence than would lose to Spence. But only Crawford knew how badly, how thoroughly, how dominantly.

The best boxer of his era is Terence “Bud” Crawford. That’s clear now, without question. He belongs among the greats. The only thing left to ponder with Crawford now is: Why didn’t we believe him all along?