Joe Burrow's Remarkable Rise Has Been Beyond Even His Wildest Dreams

When he was a boy, he imagined a different storybook fairy tale.

Joe Burrow dreamed of suiting up for the college football team he had rooted for all his life, where his father and two older brothers had played. He grew up in The Plains, Ohio, became a star quarterback in high school and led his team to a state championship game appearance. In his dreams he would go on to lift the once-proud program that he revered—Nebraska—back to prominence. Maybe, when his imagination got carried away, even to a national championship.

But Burrow’s dream was not meant to be. The Cornhuskers wouldn’t even give him a look. “They were questioning his arm strength and whatever,” says Joe’s brother Dan, a Huskers safety in the early 2000s. “All Joe ever wanted to do was play for Nebraska. It really, really hurt me.”

Burrow went to Ohio State instead, where he sat on the bench for three seasons. When he decided to transfer as a redshirt junior, Nebraska, mired in a dismal stretch, could have landed him again. The Cornhuskers passed. When asked about Burrow at the time, Nebraska coach Scott Frost said, “You think he’s better than what we got?”

And so, the fairy tale would forever remain unrealized. Instead, reality would exceed Burrow’s greatest fantasy.

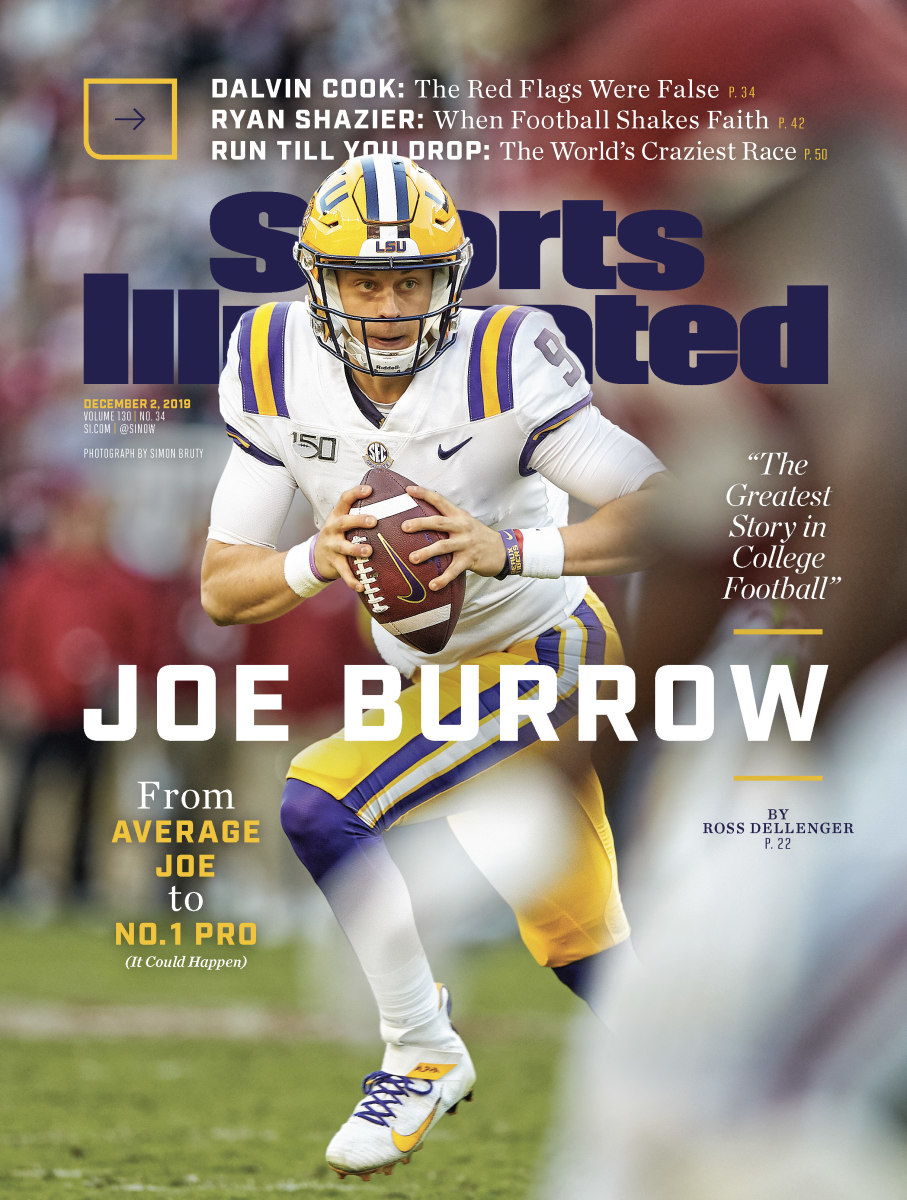

On a warm November Saturday in Tuscaloosa, Ala., LSU starting quarterback Joe Burrow sat on his nose tackle’s burly right shoulder. His arms stretched toward the heavens as he stared into a sea of cameras and stuck out his tongue. Just moments after the Tigers’ 46–41 win over Alabama, here was the new face of the game: the cartoon-loving, tongue-wagging quarterback who, after being unwanted in Lincoln then unused in Columbus, was now a legend in Baton Rouge.

“It’s been the greatest story in college football,” says Kirk Herbstreit, a longtime ESPN analyst and former Ohio State quarterback who has known Burrow since his teenage years. Consider: The Nebraska legacy snubbed by the Cornhuskers has led LSU to a 11–0 start, the No. 1 ranking and an almost certain berth in the College Football Playoff. The preseason 200-to-1 shot for the Heisman (on Las Vegas sports book betting boards long enough to include him) is now the favorite to become the second Tiger to hoist the trophy, the first since halfback Billy Cannon 60 years ago. The senior who went unlisted on many draft boards last summer has piloted a revolutionary, record-breaking offense so adroitly that he is on the short list to be the top quarterback selected next spring—maybe even the top overall player taken. One veteran NFL scout says Burrow is the most improved player from one year to the next that he’s ever seen.

From Average Joe to possible No. 1 pick? Even Joe Burrow himself wouldn’t have dreamed that up.

At 6' 4", 216 pounds, Burrow cuts the figure of a big-time college quarterback. He may even fool you into thinking he’s already in the NFL, with his businesslike attitude, low voice and intense focus. He was four-star rated at Athens High, guiding the Bulldogs to a Division III state runner-up finish in 2014 as a senior, but his limited arm strength made him less attractive to blue-blood programs. Then Ohio State offensive coordinator Tom Herman, now the coach at Texas, had to persuade his boss, Urban Meyer, to offer Burrow a scholarship after seeing him during a scouting trip.

In Columbus, Burrow had some bad luck. At first he sat behind J.T. Barrett, then behind future NFL first-rounder Dwayne Haskins, but he also broke his right thumb during camp of his second year, eventually costing him a shot at the ’18 starting job. Instead of potentially spending another year on the bench, he announced his transfer in April 2018.

Burrow whittled a list of two dozen interested schools—including Georgia, Alabama and Michigan—to two: LSU and Cincinnati, the latter a favorite to land Burrow because of his relationship with Bearcats coach Luke Fickell, the former Buckeyes defensive coordinator. “I thought he was leaning that way,” says Jimmy Burrow, Joe’s father, a former coach who spearheaded his son’s transfer recruitment.

A visit to LSU changed things. Joe Burrow dined on crawfish at a Baton Rouge restaurant, broke down film with coaches during a four-hour meeting and was wooed by one of the sport’s best known recruiters, coach Ed Orgeron.

“As we leave, Coach O is like ‘Did you get my number?’”says Dan Burrow. “That was cool. We kept in touch throughout that next week. Joe really had to sit down and think about it. He told us he wants to play football at the highest level. ‘If that’s true,’ I told him, ‘there’s LSU and there’s Cincinnati. There’s only one answer.’ ”

Joe arrived in Baton Rouge three months before the ’18 opener, won the job in preseason camp and then finished the year with a furious four-game stretch, completing 67% of his passes for 291.5 yards a game while throwing 10 touchdowns to one interception. The run convinced Orgeron to speed up his plan to overhaul an archaic, run-heavy offense.

From the first snap of 2019, Burrow has flourished in a new shotgun-based, no-huddle spread system implemented this offseason by Joe Brady, a 30-year-old former Saints assistant. The quarterback has already shattered single-season school records for passing touchdowns (41) and yards (4,014) while throwing just six interceptions. He’s the second-most prolific passer in college football (364.9 yards per game) and the most accurate (78.6%), startling statistics for a QB who last year threw for 2,894 yards and 16 TDs while completing 57.8% of his attempts.

“For Joe, [the talent has] been there,” says junior running back Clyde Edwards-Helaire. “It just wasn’t displayed a lot because of the offense we were running.”

Says an LSU football staff member, “We were asking him to play Uno when he’s a chess master.” The new offense plays to Burrow’s strength: his mind. His coaches say his football IQ is off the charts.

It was on full display in the final seconds of LSU’s Week 2 win at then No. 9 Texas, when Burrow identified a jailbreak blitz, stepped up into a collapsing pocket and, off balance with a defender in his face, whistled a pass to receiver Justin Jefferson for a 61-yard touchdown on third-and-17. Within hours of LSU’s 45–38 victory, a framed photograph of the play was hung inside the halls of the Tigers’ football operations center.

Burrow’s acumen can be traced back to parents, both of whom are educators. His mother, Robin, is an elementary school principal and Jimmy is a longtime college and high school teacher who played safety under Tom Osborne in Lincoln. The baby of the family—Joey, his family calls him—is a much younger half-brother to Jamie, 40, and Dan, 38. Around the time that Jamie started at middle linebacker for a 2001 Nebraska team that lost in the national championship game, Joey began playing youth football, transitioning from the family forte, defense, to quarterback because the Bulldogs didn’t have any other capable passers.

But just because he played offense did not mean he played soft. “He had no choice,” Jimmy says. “We weren’t going to let him not play physical.”

That mentality persists. Orgeron calls Burrow a linebacker playing quarterback. The coach jokes that he may institute a new pregame ritual to fire up his quarterback: having players bang against him in the locker room.

The Tigers point to the aftermath of LSU’s seven-overtime, five-hour, 74–72 marathon loss at Texas A&M in November ’18 in which Burrow attempted 38 passes and ran 29 times. One minute, he lay on the visiting locker room floor. The next, he was on a table with an IV in his arm and trainers feeding him cookies and applesauce. And then he saw his mom and dad, ushered inside by team personnel for one of the scariest sights any parent could see—their son a literal example of a human body giving out after a football game. The issue was serious enough that it delayed the team’s scheduled departure from Kyle Field, trainers tending to Joe before finally helping him to the bus.

“To see somebody put that kind of effort, desire and passion into a game,” longtime head LSU trainer Jack Marucci says, “it’s probably one of the first times I’ve seen anyone get into that kind of state of fatigue.”

Burrow embraces the grueling side of the game. “I enjoy getting hit sometimes,” Burrow said earlier this season. “It makes me feel like a real football player instead of a quarterback. People can look down on quarterbacks if they’re not taking hits.”

Excluding sacks, Burrow has 52 rushing attempts this year for more than 200 yards. He doesn’t run like your average quarterback, rarely heading out of bounds or sliding. Against Alabama, Burrow converted four third downs on game-securing scoring drives in the fourth quarter, two of them on runs of 15 and 18 yards.

His ability to withstand body blows endeared him not only to his new LSU teammates but also to the Tigers’ fans. Many faithful don number 9 jerseys with a Cajun-flavored alteration to his last name across their backs: Burreaux. Still, Burrow’s relocation to the Deep South wasn’t seamless. On his first trip to LSU’s dining hall teammates shamed him for eating a salad, instead pushing him to down fried chicken. (Which helps explains why Burrow gained 10 pounds his first six weeks.) The heat forced him to trim his shoulder-length locks and melted his very first pair of cleats, LSU’s outdoor artificial turf climbing well above 100º in the summer.

By the start of this season, Burrow fit in. The win over Texas in Week 2, in which he threw for 471 yards, was the first of four conquests of Top 10 teams. The upset over Alabama propelled Burrow to the top of the Heisman list.

Along the way Burrow has been fueled by the doubters who have dogged him since high school. He admits to keeping a log of the most egregious ones, as well as other slights. “Mental notes,” he says. “I still remember quarterbacks that schools took ahead of me in high school.”

He thinks about being ignored at All-Star events during high school, being neglected by Nebraska and the two failed cracks at the Ohio State starting job. “That really messed with him mentally,” says Dan. “He thought he had won the job.”

Burrow is calm and collected by nature, but sometimes the years of frustration surfaces. During a meeting with a television crew earlier this year, he confronted SEC Network analyst Jordan Rodgers, one of Burrow’s harshest critics over the last year. “The vast majority of fans I encounter have an inflated impression of Joe Burrow,” Rodgers had tweeted in August. “He was good in moments last year, but wildly inconsistent, and frankly very poor against good competition.”

The network meeting this fall came amid Burrow’s rise as the sport’s best quarterback. Cole Cubelic, another analyst present in the room, sensed tension between Burrow and Rodgers. He broke the ice by asking Burrow how much he hated Rodgers. Burrow quickly responded, “I definitely don’t like him,” and the room burst into laughter.

Burrow embraces the lighter side of things: He often sports clothes depicting cartoons—SpongeBob SquarePants, much of the time—and out of superstition wears one sock inside out each game. He holds strong views on the NCAA’s rules against allowing athletes to be compensated. “The system right now is broken,” he says. He is also forthright and open about social issues. During a summer interview with SI, he referenced a tweet from President Trump that directed four U.S. congresswomen to “go back” to their home countries.

“Why does racial inequality have to be political?” Burrow asked. “It’s basic human decency.”

Burrow’s opinions aren’t a talking point when scouts filter through the LSU football facility. According to Kevin Faulk, the former Tigers running back who is now the program’s director of player development, as many as 30 scouts visit each week. Before the Alabama game, seven scouts and a general manager were in one room analyzing Burrow’s film.

Conversations with NFL personnel about Burrow often involve Tom Brady, a teammate of Faulk’s in New England for 12 seasons. Burrow reminds Faulk of Brady in a variety of ways: poise, competitiveness and, most of all, vindictive attitude.

“You don’t think Tom doesn’t remember that he barely got drafted?” Faulk asks. “Joe remembers a whole lot of stuff.”

Burrow can seem focused squarely on football and his own pursuits. He lives off-campus, alone, and admits that there are parts of campus he’s never even seen. Having graduated from Ohio State with a degree in consumer and family finance, Burrow has a light masters-level classload that is online only.

Each Monday at the football facility, he is involved in a film-based exam of the next opponent, a test in which he must identify protection calls he’ll have to make. That means his Sundays are filled with film study. On Mondays and Tuesdays of game week, he meets with Joe Brady and offensive coordinator Steve Ensminger to pitch them his ideas on how to attack the next opponent. He pitches them ideas.

The two coaches trust their quarterback with presnap play calls; he’ll often change receiver routes based on defensive formations. “We might see it better than they do in the box or on the sideline,” Burrow says. “If I see something and want to check a play, I go do it.”

“He’s basically like a co-offensive coordinator,” Herbstreit says. “That’s the NFL model, when you have a quarterback able to invest and communicate at that level. Joe is the cutting edge of that mold. When I watch LSU, it’s not just Joe Brady’s offense—it’s Joe Brady and Joe Burrow’s offense.”

Chris Huston, a college football historian who runs Heisman.com, compares Burrow’s one-year surge with the 2002 emergence of Carson Palmer, who like Burrow had ho-hum stats as a redshirt junior before scorching defenses in his final season. But while many viewed Palmer as a top-flight talent who had, before his final year, underachieved, that isn’t the case for Burrow. “People last year weren’t asking, ‘What’s wrong with Joe Burrow?’ says Rece Davis, a longtime ESPN analyst and host of the network’s pregame show, College GameDay. “They thought they knew who he was.”

Others compare him with Heisman dark horses of the 1980s—Tim Brown, the first receiver to win the Heisman, or Barry Sanders, who burst onto the scene as a junior. In more recent history, there were unexpected winners like Cam Newton in 2010 and Johnny Manziel in ’12, but because they won the award after their first season as a starter, they weren’t written off as Burrow was after last year.

Over the summer agents and scouts told Jimmy Burrow that his son was a mid- to late-round pick. Now they’re telling him first round. The hip injury to Alabama quarterback Tua Tagovailoa could result in Burrow’s being the first quarterback drafted or possibly the No. 1 overall choice. His stiffest competition may be Oregon quarterback Justin Herbert, as well as defensive lineman Chase Young of Ohio State.

“That toughness and competitiveness gene he has is a very good indicator of how he’s going to do at the next level,” says Daniel Jeremiah, a former NFL scout for the Ravens, the Browns and the Eagles, who’s now an analyst for NFL Network. “You start listing all of his good qualities and you realize how much you like him. You ask, ‘What’s wrong with him?’ Well, he doesn’t have a huge arm. Who cares?”

The biggest debate in the 2019 draft was Kyler Murray’s height. This time it will be Joe Burrow’s arm.

“I think he’s got the real chance of being the No. 1 overall pick, but it’s still hard to convince some people because a guy doesn’t have the great body or great arm,” says one NFL scout. “He’s not a prototype guy from those standpoints. Maybe the NFL should change its prototype.”

Burrow still has time to improve his draft stock. He has a national title to chase. He may have to beat his former team to do so: Ohio State is No. 2 in the CFP rankings. Burrow remains close with several figures from his days in Columbus, including Meyer, who texts him before and after nearly every game.

For the rest of this season, at least, the Burrow family’s allegiances are to LSU. Before most games, you’ll find Joe’s parents and brothers under a tent in the shadow of Tiger Stadium, a Burrow Gang banner marking their location as they partake of gumbo and jambalaya.

All the members of the family are trying to wrap their minds around this whirlwind. “It blows my mind where it started and where we are today,” says Dan. “I thought he could be here and do it, but it’s mind-blowing for me—he did it. He’s here. It’s real. It’s crazy.”

Matt Porter is in a state of disbelief too. Back in June, Porter, an LSU fan living in Fort Lauderdale, put $50 on Burrow to win the Heisman Trophy at 200-to-1 for a potential payout of $10,000. When Burrow became a serious contender, in late October, Porter’s gambling outlet offered him $3,865.38 to cash out. He passed.

And now? Porter is already making plans to take his girlfriend to the Bahamas.

The long shot is now a veritable shoo-in. And that’s no fairy tale.