Colorado Ready to Erupt for Deion Sanders’s Home Opener vs. Hated Rival Nebraska

It’s a classic September day on the front range of the Rocky Mountains: bluebird sky, thin air, ancient flatiron rock formations jutting up sharply above the Boulder campus of the University of Colorado. It’s so refreshingly picturesque that everyone should be outdoors.

Yet there are big doings indoors. In the campus bookstore, the checkout line is a dozen deep and constantly replenishing. It’s roughly 48 hours before the biggest home football game in more than two decades, Saturday against Nebraska, and a conga line of students are toting their fresh gameday merch to the cash register. They are riding a sudden avalanche of football fever that has broken through years of ossified indifference.

“We’ve seen a lot of traffic,” says CU Bookstore associate buyer McKenna King. “There’s lots of buzz, very electric on campus.”

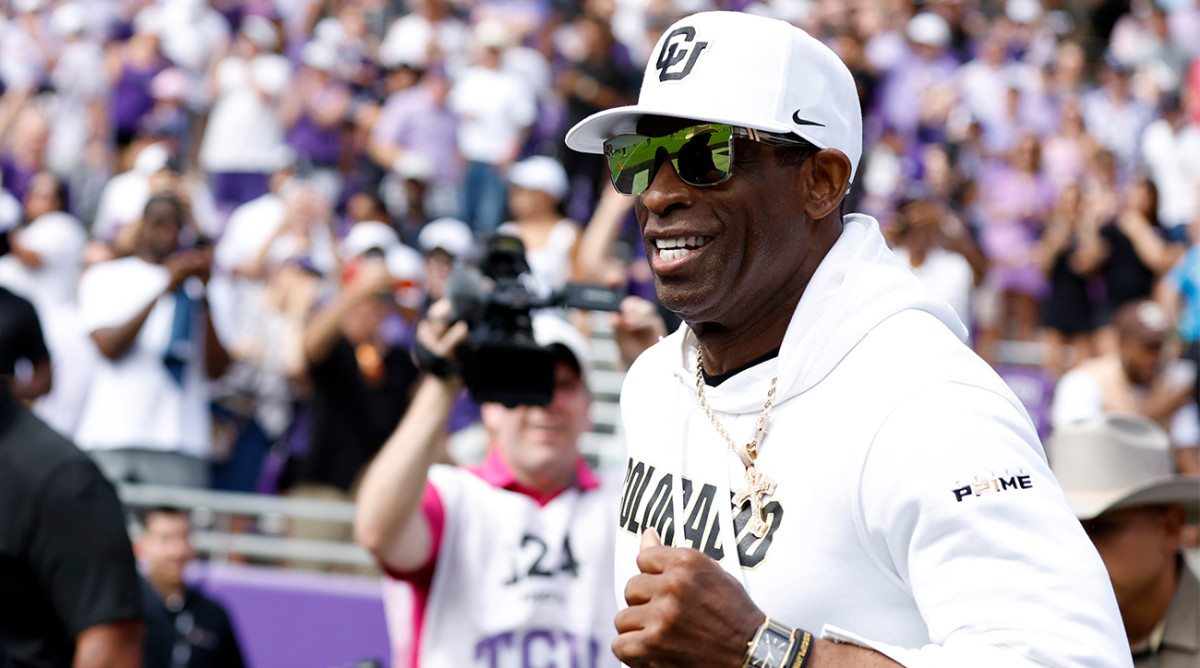

Traditional Buffalo logos are flying off the racks. But the shirts from the display titled “Coach Prime Gear” are brisk movers as well. Those feature a couple of Deion Sanders’s instantly marketable quips after arriving as Colorado’s savior-coach last winter.

“I Ain’t Hard 2 Find,” reads one. “We Coming,” reads another. “Coach Prime” is the more prosaic third option. Glittery black-and-gold cowboy hats round out the display, a nod to the western lids Sanders has worn frequently since arriving here.

A short walk from the bookstore, construction is underway on the Fox “Big Noon Kickoff” stage. The TV network will broadcast its pregame show there as the launching pad into a Saturday slate of games, starting with the Cornhuskers vs. the Buffaloes. Sanders’s Colorado debut last week, against TCU, also was Fox’s noon game, and it drew 7.26 million viewers—a staggering number for two teams without massive fan bases.

After the Buffs delivered on an offseason of unprecedented hype by stunning the Horned Frogs as a three-touchdown underdog, the home opener has taken on a new dimension.

This game should draw another huge TV audience, in addition to the sellout crowd at Folsom Field. The get-in price on the secondary market for the Nebraska game is $476, according to one website that tracks ticket prices, which it says is more expensive than any NFL opener this weekend. Colorado has never sold every ticket for all its home games, according to program historian and retired sports information director David Plati, but four of the six this year are already sold out, with expectations that the other two will get there as well.

A football program that was dead upon Sanders’s arrival last winter has been given a life-sustaining round of CPR: Coach Prime Revival. This improbable coupling of Sanders and Colorado is captivating the football-watching public nationally, but it is especially dramatic and euphoric here at the source.

“It’s crazy around here,” says Darian Hagan, quarterback of Colorado’s 1990 national championship team, a former Buffaloes assistant coach and the program’s current executive director of community engagement and outreach. “I have friends and family members asking me for tickets for this game. My response is, ‘You didn’t come when I played and you didn’t come when I coached. Why do you want to come now?’ It’s been amazing. We haven’t had this much excitement around here in years.”

Watch college football with Fubo. Start your free trial today.

In early October 2022, Colorado athletic director Rick George convened his first Zoom call with two men he had enlisted to help him find a new football coach—former Buffaloes quarterback Joel Klatt, now a Fox TV analyst, and former Buffaloes coach Gary Barnett, now the team’s radio analyst. (Klatt played for Barnett from 2002 to ’05.) George fired Karl Dorrell on Oct. 2, a day after a 43–20 loss to Arizona dropped the team to 0–5. It was time to find someone capable of fixing a broken program.

“We had a list of about 30 people,” Barnett recalls. “We had all put in names, and some people had brought some names to us. Somebody had dropped in [Kansas coach] Lance Leipold’s name, [former Texas coach] Tom Herman, [current Nebraska head coach] Matt Rhule was involved early on—a lot of guys. There were a couple guys we axed right away. As much as they’re probably good names, they’re not a good fit.

“We get to the end of the call, and Rick says, ‘By the way, Deion Sanders’s agent just called.’”

Barnett was skeptical. He figured Sanders would be throwing his hat in a lot of rings in the midst of a wildly successful second season at FCS school Jackson State, and Colorado wouldn’t be his preferred destination. There were no natural ties. But Barnett agreed with the others that Sanders belonged on the list and deserved full consideration.

At their next meeting, George said he spoke with Sanders and believed he was seriously interested in the job. He made a trip to meet with Sanders’s agent while the process went on with further vetting of other candidates.

George and Barnett conducted a couple of interviews. Klatt talked to a couple of candidates on the phone. Then at their third meeting, George said he was sold on Sanders. Barnett’s recollection of George’s assessment: “Guys, I’ve got to tell you—I really like Deion Sanders. I’m really impressed by his whole organization. He’s way ahead of everyone in the transfer portal, way ahead on NIL, and I think he’s legitimately interested.”

George and Klatt were onboard with offering Sanders the job. Barnett, age 76 at the time, needed a little bit more convincing about such an outside-the-box hire—but not much.

“I don’t think anybody else can change this the way it needs to be changed any better or quicker,” Barnett says he told the others. “We are in a desperate situation. So I’m all in, but we better find No. 2 in case this falls through.”

That became Barnett’s job, while George worked the Prime candidate. A key milestone in the process: persuading the university to relax its transfer policies, allowing Sanders to immediately upgrade the talent level. Contract numbers were agreed upon—though on the night of Nov. 19, after Colorado fell to 1–10 in a 54–7 debacle at Washington, George texted Sanders’s agent that he was adding an extra $500,000 to the deal, “just in case Deion saw that.”

With an undefeated season on the line, Sanders insisted on finishing the season at Jackson State. He coached the Tigers to a victory in the SWAC championship game to go 12–0 on Dec. 3, then told his team afterward that he was taking the Colorado job.

"In coaching, you either get elevated or get terminated. Ain't no other way," Sanders told his team. “I’ve chosen to accept the job elsewhere next year. I’m going to finish what we started. We going to dominate. I'm going to be here until that end and that conclusion."

Sanders coached Jackson State in the HBCU Celebration Bowl against North Carolina Central of the MEAC two weeks later. After an upset loss in that game, he fully settled into an unfamiliar place to consummate an improbable marriage and begin a massive rebuild.

The video of Sanders’s initial meeting with his new team was his first viral moment with the Buffaloes. It was part warning shot, part rallying cry, part church revival. “I’m coming,” Sanders declared several times, an utterance Barnett says the coach first used with George during the hiring process to reassure him that the deal was done.

“I know you’re nervous,” Sanders told George. “But I’m coming.”

That was the meeting in which Sanders declared he was bringing his own luggage, “and it’s Louis.” The key pieces of luggage who made the trip from Jackson State: Sanders’s two sons, quarterback Shedeur and defensive back Shiloh, and two-way player Travis Hunter. What they did against TCU fulfilled the prophecy Deion laid down in that first meeting.

But those three were just part of the roster turnover, an overhaul unlike anything ever seen at the FBS level. He brought in 86 new players—53 of them transfers—with just 10 scholarship players remaining from the Dorrell era. “It had to be done,” Sanders said.

But would this large-scale chemistry experiment work right away? The hype train appeared to be moving too fast for the mule train of re-creating a team on the fly.

Colorado spring football traditionally is a complete afterthought on the sporting calendar in a state with all four major men’s pro sports franchises and an abundance of outdoor activities. The Nuggets and Avalanche were in the playoffs by then, the Rockies had started their season, the Broncos are constantly in the news and the mountains beckon.

The program’s record attendance for a spring game was 18,000. Sanders brought 47,000 to Folsom Field in a snow storm. “He doesn’t like being called a celebrity coach,” Plati says. “But to get 47,000 for the spring game probably signaled what eventually was going to happen under Deion.”

Still, doubts remained about what this Colorado team would look like playing against someone other than itself. Line play was a massive question mark, as was depth. Opening on the road in frying-pan heat against an opponent that played in the College Football Playoff championship game? The 20.5-point spread actually seemed too low to many.

Then Colorado began the season with a lightning strike—a three-and-out forced by the defense, followed by a 13-play, 73-yard touchdown drive. The Prime era arrived with all the panache its leader could have envisioned, and it was sustained. The Buffaloes led most of the game but trailed in the second half, appeared to be on the ropes, then kept making plays and scoring touchdowns in a 45–42 triumph. Sanders’s sons excelled: Shedeur passed for a school-record 510 yards, and Shiloh led the team in tackles with 10.

Only one other FBS coach in the last decade has won his debut at longer odds than Sanders did, and that came later Saturday (G.J. Kinne and Texas State, a 27.5-point underdog, over Baylor). This was a called shot of Ruthian proportion.

“All of a sudden overnight, we became viable,” Barnett says. “Every sports show is talking about us and every recruit. We went from literally being the worst team in college football to one of the most relevant without playing a game. And now, having played a game, we’re more than that.”

Sanders was in full showman mode afterward, barking at reporters about having “receipts” on all the doubters. It was a florid, made-for-TV display that underscored Coach Prime’s ability to steal a spotlight and direct its shine where he wants it. His team’s performance on the field—and his in front of a microphone—will play very well with recruits. (Class of 2025 quarterback Bryce Underwood of Michigan, the nation’s No. 3 recruit and top QB according to Rivals.com, said this week he will attend Colorado’s Sept. 30 home game against USC.)

“When the camera’s not on him, he’s a totally different person,” Hagan says. “When those cameras come on, oh my God. He puts it on. But the players believe in him, the staff believes in him, the fans believe in him. So do your thing, brother.”

One specific comment that will resonate with recruits: when Sanders completely broke coaching convention during his halftime interview. He all but bestowed the biggest individual award in the sport to two-way revelation Hunter just 30 minutes into his first FBS game, proclaiming the “Heisman would be in his crib chillin’” if the Buffaloes had completed a couple of long passes to Hunter.

Hunter did his best to back that up against TCU with a performance unlike anything we’ve seen in the last 35 years. The sophomore had 100 yards receiving and a key interception while playing a mind-boggling 129 snaps of combined offense and defense.

Question: Is that even remotely sustainable over the course of a season?

Barnett’s answer: “He can do it. But he’s not from this planet.”

He continued: “What I think is going to happen, it’s going to knock off that glass ceiling that everybody else has put on their players, that they can’t play both ways. You got a player like him? You better play him. And he wants to play—he doesn’t want to come off the field. I think coaches will watch this and say it’s doable.”

So now the unexpected biggest show in college football comes home. Last time Boulder jumped like it will Friday and Saturday was the day after Thanksgiving in 2001, when Barnett’s team annihilated No. 1 Nebraska 62–36 on its way to the Fiesta Bowl.

Fittingly, the opponent is again the Cornhuskers—no longer conference brethren with the Buffaloes, but still a program Colorado fans love to hate. From 1962 to 2000, Nebraska won 34 out of 39 meetings, with one tie. Knowing the lopsided nature of the rivalry, Colorado’s best coach—Bill McCartney—put a bull’s-eye on the Cornhuskers in the 1980s and declared them Public Enemy No. 1. On a schedule in the locker room that listed every other opponent in either black or gold lettering, Nebraska was in red—and that was the only red allowed in the facility year-round.

Sanders hasn’t gone out of his way to acknowledge much of anything that happened at Colorado before his arrival, but he has picked up on the Nebraska dynamic. Once again, red is prohibited in the facility. “This is personal,” Sanders declared this week.

“I appreciate these guys buying into that tradition,” Hagan says. “I still don’t have anything red in my house. I was raised as a Buff to not like Nebraska. We’re ready for those dudes.”

The night before home games, the Colorado tradition is for a parade featuring the team through Pearl Street Mall, the cultural center of Boulder. The outdoor pedestrian area is the embodiment of this offbeat college town, an eclectic mix of hippies, rich fashionista students and street performers. If you walk through there at any point in time and don’t see a shirtless guy with a ponytail sitting on the ground playing bongos, something is off.

But Friday night, Pearl Street likely will look less Bohemian and more like something out of the Southeastern Conference. Downtrodden Colorado has been given CPR and is ready for its Coach Prime Revival.