The NCAA Has Let Name, Image and Likeness Become the Wild West

This is what has happened in college sports since the Supreme Court allowed athletes to capitalize on their name, image and likeness:

Angel Reese went from seldom-used Maryland freshman to NCAA Most Outstanding Player for LSU. Kirby Smart finally won a national title, and then another. Livvy Dunne became a celebrity. Michigan won three straight Big Ten football titles. The Pac-12 imploded. The College Football Playoff announced it would expand from four teams to 12. Roy Williams and Mike Krzyzewski retired. Caleb Williams went from backing up Spencer Rattler at Oklahoma to winning the Heisman at USC to being the likely No. 1 pick in the 2024 NFL draft.

This is what has not happened in college sports since the Supreme Court allowed athletes to capitalize on their name, image and likeness:

The NCAA created permanent NIL rules.

In July 2021, around the time when NIL deals became legal, the NCAA adopted an interim NIL policy. Some administrators have hoped the government would take care of the rest, because Congress is known for acting quickly in unison to address a complex problem, but shockingly that didn’t work. The NCAA has indicated it might adopt a permanent policy in January; you can read a summary of the likely policy here. But it has been two and a half years. Iowa’s offense moves faster than this.

The NCAA is, of course, just an association of hundreds of schools, and those schools have not figured out how to handle this. New NCAA president Charlie Baker has said the failure to implement clear NIL rules immediately was a “big mistake,” which is a sign he is more interested in navigating through the new world than wishing for the old one. But he is right—it was a big mistake. This has predictably created the exact environment schools claimed they wanted to avoid: a free-agency market where players act like professionals, selling their services to whoever offers the most money.

That is still illegal, by the way. Schools can’t use NIL money as a recruiting inducement. They are not allowed to arrange specific NIL deals for individuals. They are allowed to partner with collectives, and encourage boosters to donate to those collectives, but they are not allowed to tell the collectives how to spend the money.

Those are the “rules.” Here is the reality, from Nebraska coach Matt Rhule in a recent press conference:

“Make no mistake that a good quarterback in the portal costs, you know, a million to $1.5 million to $2 million right now, just so we're all on the same page. Let’s make sure we all understand what’s happening.”

And here is Wake Forest coach Dave Clawson on his former quarterback, Sam Hartman, who left for Notre Dame: “[Notre Dame] bought him and rented him for a year, and now they love him. This is where college football is."

Then there is the Kansas men’s basketball program, which is the equivalent of three-card monte: Is the rule here? Or there? You think it’s there? Nope, it’s here!

Last fall, Kansas coach Bill Self served a four-game suspension because the school’s apparel sponsor, Adidas, used its money to steer recruits to Kansas.

Then, this past spring, Michigan star Hunter Dickinson left for Kansas, citing NIL money as a factor. He told ESPN, “If I wanted to just go to the highest bidder, then it wouldn't be Kansas.”

This fall, Dickinson signed an NIL deal with … you’ll never guess … Adidas!

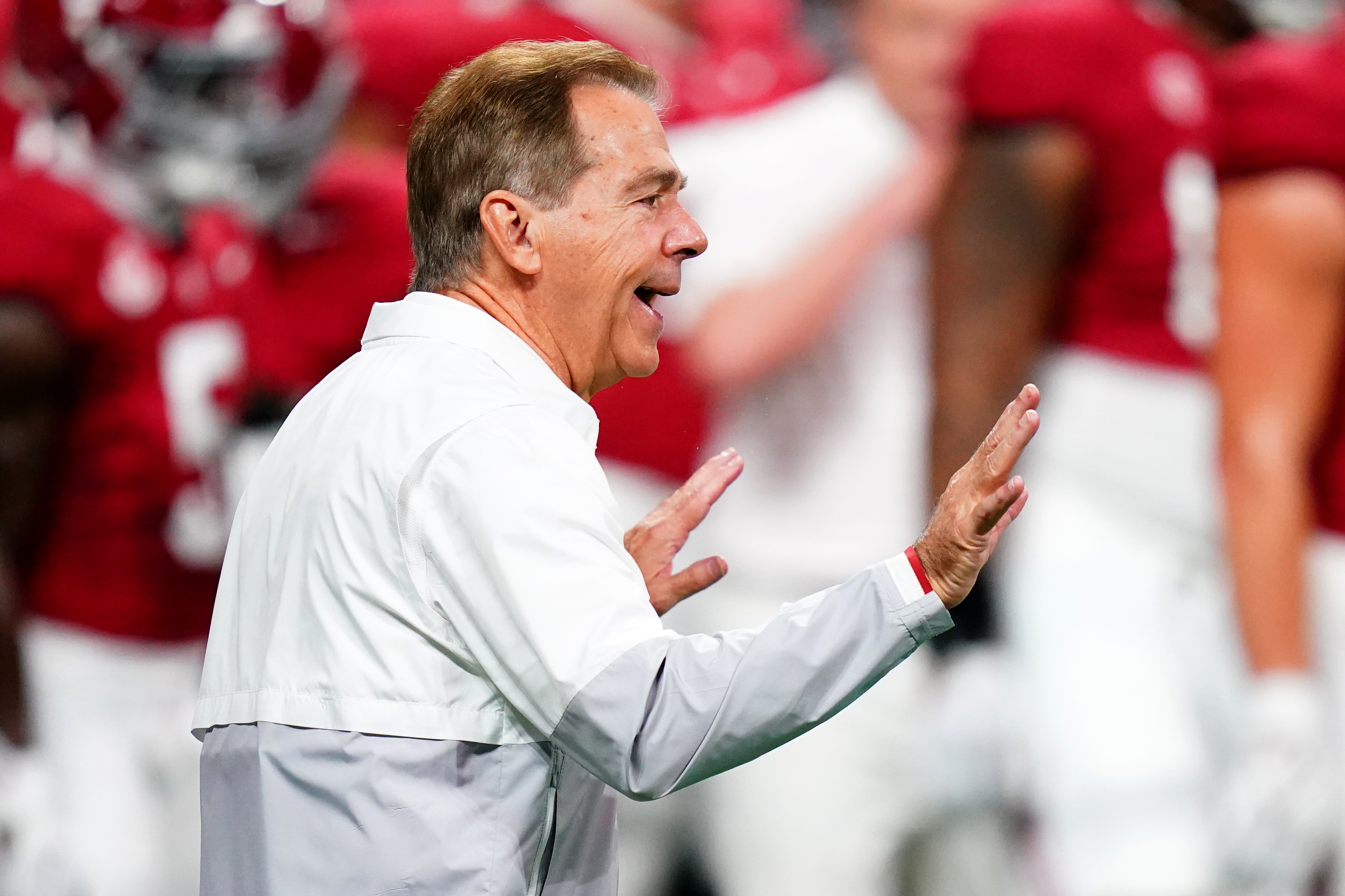

When Dickinson said there were higher “bidders,” did the NCAA call him? Did it ask Clawson why he said Notre Dame bought his quarterback? When Nick Saban said Texas A&M “bought” its top-ranked recruiting class, did that trigger an NCAA investigation? When coach after coach has said publicly that schools are using NIL money as a recruiting inducement, and coach after coach has pleaded with boosters to donate to collectives to keep teams together, who is monitoring them?

The NCAA may well be investigating all of these situations. The enforcement staff doesn’t reveal inquiries. But there is a clear feeling in college sports that anything goes because nobody stops it.

This is not a rant against NIL or in defense of “amateurism.” If Caitlin Clark can get rich selling insurance while she plays for Iowa, good for her. College coaches make millions, so college players should be able to make millions, too. It is probably only a matter of time before colleges pay players directly. But every major professional sports league has rules governing financial transactions and a mechanism to enforce those rules, and college sports needs both desperately.

You don’t see an NBA star sign a free-agent contract and then announce that nine teams offered to circumvent salary-cap rules more egregiously than the one that signed him. Yet it is widely assumed in college sports that for more than two years, some schools have used NIL money as a recruiting inducement with no fear of getting caught, while others have been more cautious.

If the NCAA adopts all of the proposed rules in January, it would require athletes to report any NIL deals larger than $600 to their school—and to “disclose” all current and previous NIL deals before signing with a school. Those disclosures would be anonymous; the idea is to gather data, not evidence. Agents and financial advisors would “be able to voluntarily register with the NCAA.” Athletes would be required to attest that “no staff members at the school promised benefits related to NIL as a condition of enrolling or remaining at a school.” The NCAA has already lowered the burden of proof for NIL violations under its “presumption rule.”

That is a start—but only a start.

What happens if Nike offers the No. 1 player in the country $5 million a year to sign with a specific Nike school? Is that a recruiting inducement designed to benefit the school—or a business transaction designed to benefit the player and Nike? How do you tell the difference? (Some NIL providers try to get around this by offering players a contract contingent on the athlete playing Division I football in a specific state—without mentioning a specific school. Whether the NCAA views those deals as legal is not clear.)

Do schools even have the legal right to require athletes to disclose their personal business arrangements? Or would they only have that right if the athletes were (don’t say it … don’t say it) employees working under a collective-bargaining agreement?

These are very difficult questions to answer. But the NCAA has to try. Coaches are entitled to know the regulations of their profession. Athletes should know their value in the marketplace. Schools will always have different resources, but they shouldn’t play by different rules. In the meantime, the transfer portal churns, some coaches are preparing bids, and others just check their watches, hoping for answers that should have come two years ago.