College Football Coaching Carousel Proves Hypocrisy of Calls to Rein In Player Transfers

As the college football hiring cycle takes a late-but-massive spin into January, one eternal truth is more stark now than ever: one program’s need becomes another program’s wreckage.

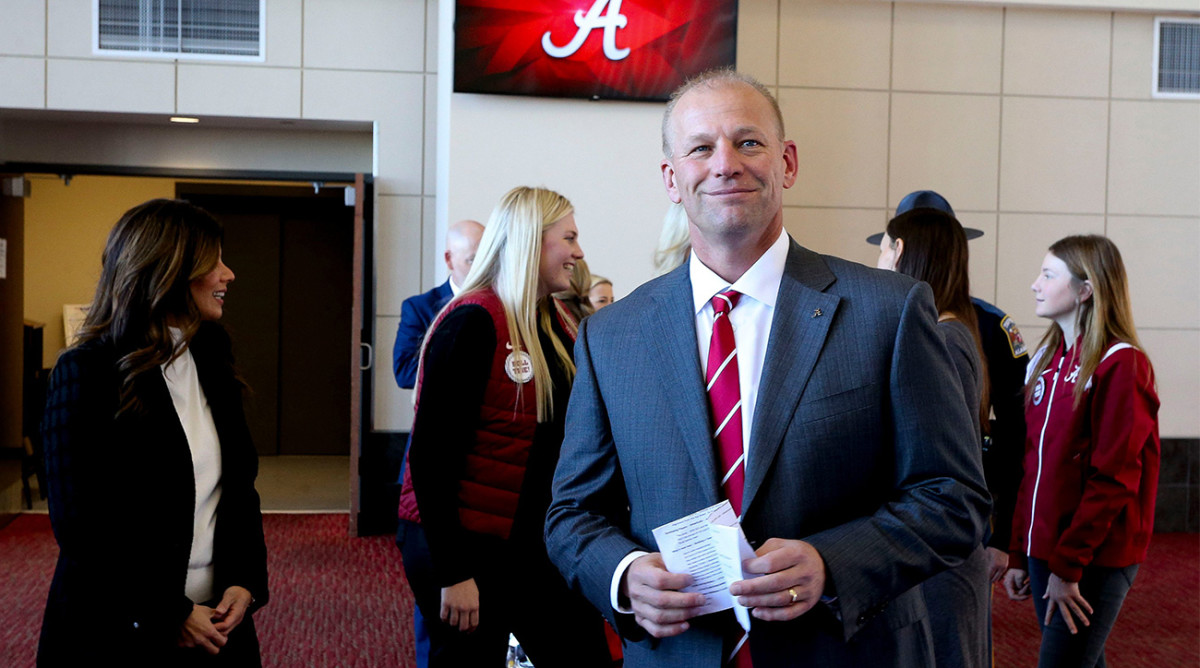

Alabama needed a coach, so it pillaged Washington for savior Kalen DeBoer—and a good portion of his staff, and probably a few players. Coming less than a week after losing the national championship, and on the heels of multiple star players declaring for the NFL draft, and with star transfer quarterback Will Rogers re-entering the portal, Huskies fans were devastated. One of the best seasons in school history crumbled to dust in a week.

Then two days later, Washington pillaged Arizona for savior Jedd Fisch—and, perhaps his star quarterback, Noah Fifita, and star wide receiver, Tetairoa McMillan. On the heels of a 10–3 season, the program’s best record in 25 years, it is now the Wildcats’ fans who are devastated. Meanwhile, Huskies fans felt their outrage dissipate quickly.

Arizona now will do the coach and player poaching. Hunker down, San Jose State.

In the open-transfer world college sports currently occupies, schools can rebuild or be depleted in a hurry. For the fans whose programs are being raided, these are tough times. But as the food chain has forever shown, there is always more vulnerable prey to hunt. Those tough times might only last a few days.

What has upped the stakes—and stoked fan outrage—is the fluidity of player movement. That’s the kind of thing that has people renewing calls for rule changes and decrying the state of college sports. In reality, the athletes are simply getting some of the latitude the adults have always enjoyed.

You can ask for Congressional intervention if you want. But there wasn’t anyone wanting to overhaul the system when super agent Jimmy Sexton engineered an all-time power move last week. Sexton’s A-list client Nick Saban retired, and suddenly all the successor candidates at Alabama were straight from the Sexton rolodex: Dan Lanning of Oregon; Steve Sarkisian of Texas; Mike Norvell of Florida State; DeBoer of Washington. It was Sexton’s market to manipulate.

Lanning quickly pulled out. Having gotten a raise and an extension in 2023, he didn’t play the Alabama job for more money. But both Sark and Norvell did, landing big raises while DeBoer landed the actual job. Were they ahead of DeBoer on the Alabama wish list? Who knows for sure. But Sexton moved chess pieces to make several of his clients richer behind closed doors.

Sexton plays the game at stakes of tens of millions of dollars per transaction and everyone shrugs. Lucrative contracts are broken, massive buyouts are paid, nobody’s word lasts for long—that’s the coaching business we’ve grown accustomed to.

Meanwhile, agents facilitating athlete movement and playing one offer against another (low-seven-figure offers at the very richest) have been deemed an existential threat to college sports. The double standard of what causes outrage in college sports remains intact, but the players cannot be hemmed in as they once were. It’s time to deal with it.

Without question, the timing of this current spasm of potential player movement is problematic if you take into account the quaint notion of the academic calendar. (For the coaches, as always, the timing is only bad for the program you’re leaving, never the one you’re going to.) If, say, Fifita and McMillan want to join Fisch in Seattle, some hoops will have to be jumped through in order to have them on campus immediately. The winter quarter at Washington started Jan. 3.

But accommodations assuredly will be made to keep the football machinery humming. They always are.

Beyond program-on-program crime, the latest coach poaching has led to declarations that this is proof the SEC and Big Ten will take what they want from the rest of the nation as they continue to distance themselves in terms of revenue. That may ultimately be the case, but this past week doesn’t prove that point.

Washington didn’t necessarily get Fisch because it is headed for the Big Ten while Arizona is headed for the Big 12. If the two schools were remaining in the Pac-12, Fisch might still have made that move. Washington has almost always been a superior football program to Arizona, and the Wildcats’ current budget crisis creates its own internal uncertainty. (The university is dealing with a $240 million budget shortfall.)

If the day comes that the Jedd Fisches of college football are leaving 10-win programs on the rise for Indiana, Illinois or Rutgers, go ahead and sound the alarm that the football world is narrowing to two leagues. At present, going from Arizona to Washington is hardly an unnatural career move for a football coach.

On the SEC front, the fact that Mike Norvell is still the coach at Florida State should tamp down armageddon fears. In fact, if Norvell turned down Alabama to stay in Tallahassee, it would seem to hurt FSU’s argument that it simply cannot keep pace with the SEC on its current annual revenue stream as a member of the ACC.

That’s an argument the Seminoles are taking to court—in an effort to sue their way out of the ACC, at a rate somewhere well south of the roughly $500 million exit fee they could incur under the current grant-of-rights agreement that extends to 2036. (Another contract to be broken in College Sports, Inc.) After going 13–0 and beating two SEC opponents, then retaining its coach amid presumed SEC blueblood interest, it seems like Florida State just might be able to survive as a national power on its spindly current athletic budget of $161 million.

So this sudden and significant coaching movement of January is probably not attributable to conference realignment. It’s simply the nature of how the sport tends to operate. The apex predator eats first, and the rest of the food chain reacts accordingly.

The difference is the player transfers that follow. The athletes now have actual freedom of movement options when their circumstances abruptly change. That’s not a sign of the apocalypse; it’s a sign of progress.