Looking Back at People Behind Hank Aaron's Record 715th HR

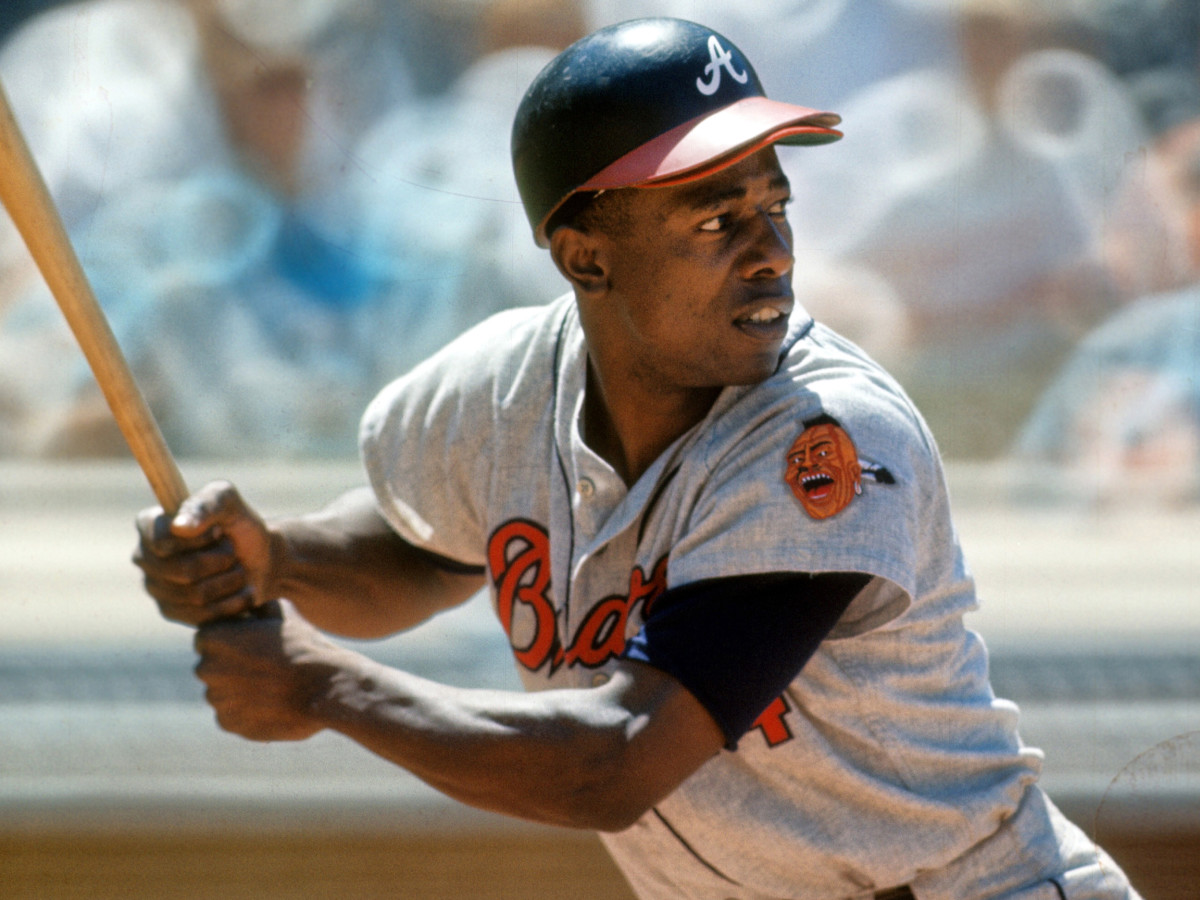

If he hadn’t been a baseball player, Henry Aaron might have been a carpenter. He was one of eight children, and when he wanted something, he usually had to make it himself. At age six he collected scrap lumber to help his family build their house in Mobile, Ala. He says he always enjoyed working with wood.

He did his best work with a bat, however. “I’m glad I went another way,” he says. “I figured out I could hit a baseball with [wood].”

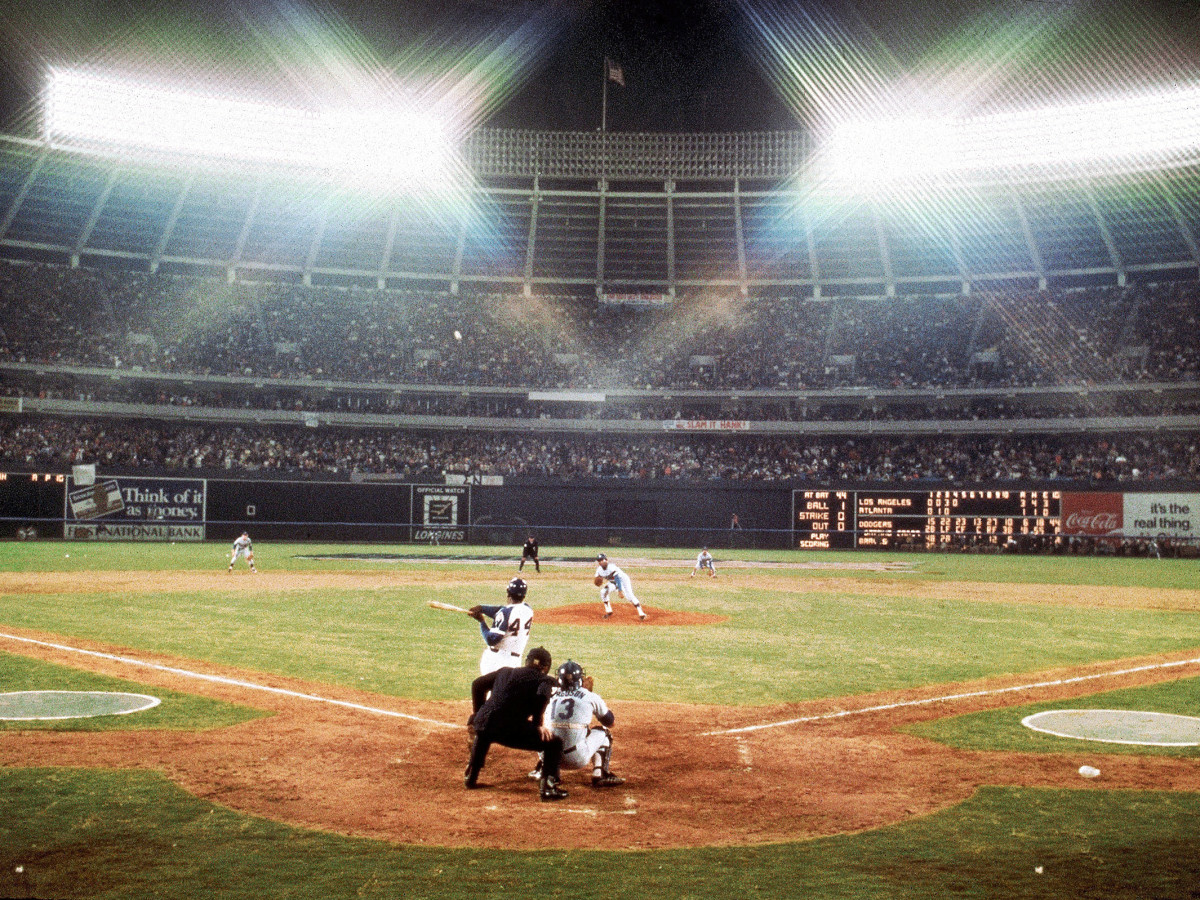

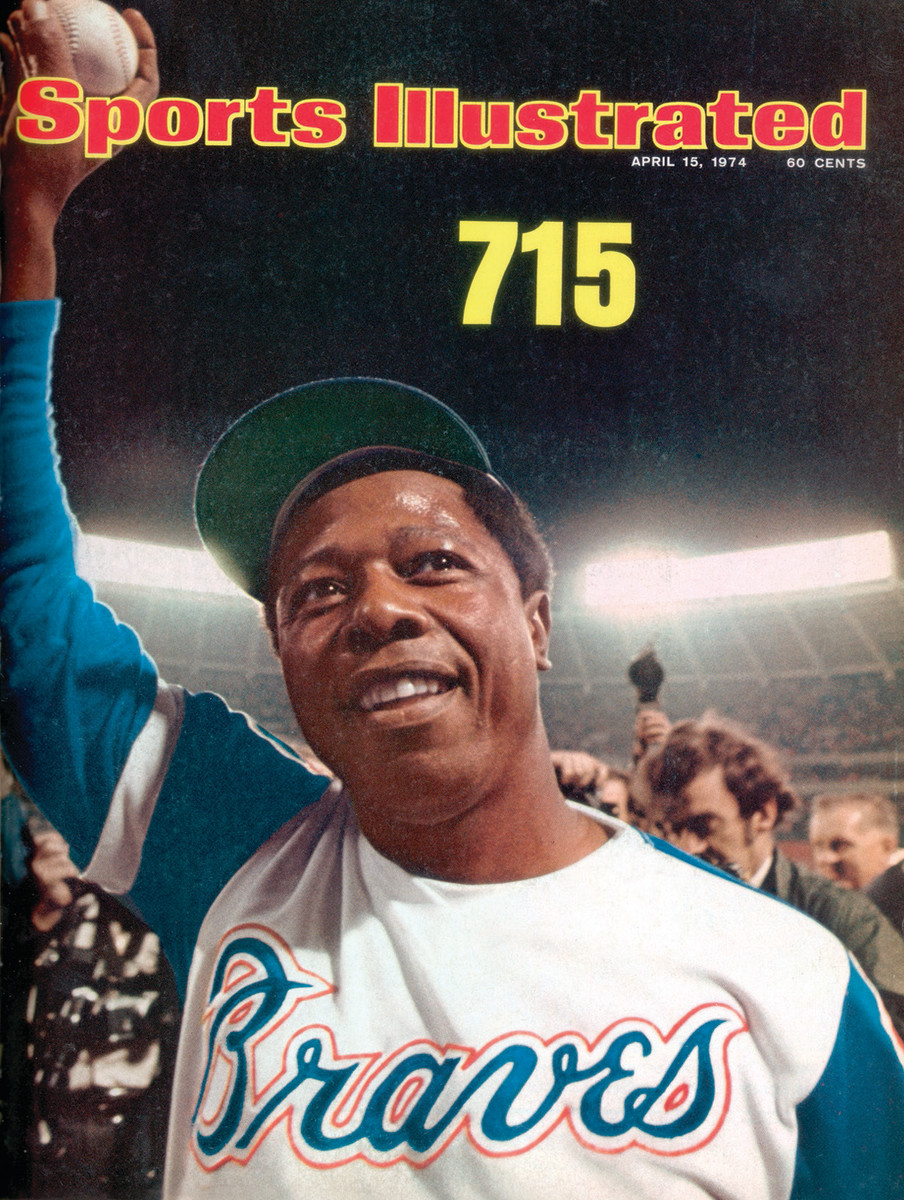

The ball that crowned Aaron as the sport’s home run king was marked with serial number 12‑12‑2‑2 and with clubhouse attendant Bill Acree’s signature in invisible ink. Aaron hit number 715 into the Braves’ bullpen on April 8, 1974, to eclipse Babe Ruth’s record. But a moment that should have been among the happiest of his life was instead only a relief; he barely remembers rounding the bases.

The media scrutiny leading up to that moment had been intense: Reporters had to make appointments to speak with him, and they came from all specialties to cover the chase. (Braves radio broadcaster Milo Hamilton remembers waiting in line for an interview behind a man whose last question was, “And by the way, Mr. Aaron, do you hit righthanded or left?”) But the fact that he was a black man chasing the most important record of America’s pastime, held by a white icon, meant he was also in near-constant- danger. The Braves hired an Atlanta police officer, Calvin Wardlaw, to accompany their star everywhere and registered Aaron in hotels under phony names. The team forwarded the pounds of hate mail and death threats he received to the FBI.

There had been scares throughout his career, but the vitriol increased once he passed 700 homers. Someone threatened to kidnap his daughter Gaile, a student at Fisk University in Nashville. One letter promised that a man in a red jacket would shoot Aaron during a game in Atlanta; Aaron urged his teammates not to sit too close to him in the dugout. Even autograph seekers terrified those around him; the flash of a metal pen could look like that of a gun.

The evening he broke the record—in the Braves’ home opener against the Dodgers—was no less frightening. Aaron had received letters from people promising to kill him before he touched home plate. The Braves stationed 63 patrolmen around the ballpark that night, three times as many as usual. Wardlaw sat close to the field, hand on the .38 caliber gun he kept in his binocular case.

As Aaron circled the bases and his teammates celebrated, his family could not relax. At home plate his mother, Estella, hugged him so tightly that he thought she’d break him. It was less a tender moment than an attempt, she later said, to shield her son from snipers.

At last the game ended, and Aaron went back to his career and his life. He has refused to comment on his place in the record book as players suspected of steroid use approached and surpassed his numbers, and he doesn’t keep any memorabilia—other than the hate mail, which he still stores in the attic of his Atlanta house—having donated it all to the Hall of Fame.

Once a year he travels to a ranch owned by former Atlanta pitcher Pat Jarvis near Lake Oconee, Ga., 80 miles east of Turner Field. About 10 former Braves spend the weekend catching up and talking about their baseball accomplishments. “Home runs that were hit 250 feet become 400‑footers,” Aaron says.

Aaron broke his left hip after slipping on ice in February, and the last time he swung a bat was 15 years ago. Now he focuses on his roles as a Braves senior vice president and founder of the 755 Restaurant Corporation, which owns 23 Popeye’s franchises and two Krispy Kremes, all in Georgia. He sits on the boards of the Atlanta Falcons and Designer Shoe Warehouse. His Chasing the Dream Foundation awards 44 grants every year through the Boys & Girls Club.

When he watches a game today—usually the Braves, on mute (“I don’t need to listen to an announcer,” he says)—he marvels at the athleticism. “Did I used to do that?” he says. “Did I used to run that way?”

Even though Aaron doesn’t like to relive the home run chase, he reminds himself that mixed in with the hate mail were letters from people who had named children after him, who had been distracted from their own difficult lives, who had been inspired. The quest for 715 was challenging for Aaron and his family, but for many other people in attendance that night, it was a moment that continues to resonate.

THE ASSISTANT

Through all the fireworks and celebration, Carla Koplin Cohn's most vivid memory of Aaron's record-breaking night is the deep feeling of relief. "I just thank God it's finally over," Aaron told the crowd, and no one understood what he meant better than Cohn, his personal secretary. "He just didn't have a moment to himself," she says of the three years between his 600th and 715th home runs, "and they came through me to get to him."

As an assistant to the director of a sports camp in which Aaron had an ownership stake, Cohn (then 23) so impressed the ballplayer that he insisted that her employment by the Braves be written into his 1972 contract. She opened thousands of his letters and separated the death threats (some of which were directed at her, a white Jewish woman working for a black man in the South) from the legitimate business correspondence and the kind words sent by people he inspired. She scheduled his personal appearances and even made and delivered lunch to his children.

Cohn moved to Milwaukee when Aaron was traded to the Brewers in 1975 and eventually on to New York City, where she spent the next 25 years as a wife and mother. But when her daughter went to college, Cohn started an event company, Sweet Celebrations, in 1997. After six years of wrangling the most famous athlete in the country, it was nothing to plan a few dozen birthday parties, bar mitzvahs and weddings a year. In 2009, Cohn retired to Boca Raton, Fla., where she's trying desperately to improve her golf game.

Cohn and Aaron have remained close. He gave a speech at her daughter's wedding, and she has attended all of his major events. She still gets emotional when she speaks of him, and when she closes her eyes, she says, "I still think of him as 39 years old. I didn't realize that I was part of history then, because I didn't see him like that."

THE PITCHER

The pressure didn't faze Al Downing. The marching bands that crowded the bullpen before the game and prevented Downing from getting a normal warmup didn't, either. The intermittent rain and pregame ceremonies? No big deal. Downing had debuted in the majors with the Yankees in July 1961, so after living through 2½ months of delirium surrounding Roger Maris's chase of Babe Ruth's single-season home run record, he was ready for this challenge too. (He has always suspected that Dodgers manager Walter Alston chose him to start Aaron's potential record-setting game for exactly that reason.)

So when Downing walked Aaron in the first inning, that wasn't nerves. And when he left a fastball a little up in the fourth, that was just baseball. "I was not overwhelmed at all," he says. "He was the greatest home run hitter of all time. You're more upset if it happened with a guy who was not a good hitter."

Aaron's 715th wasn't a defining moment for Downing, who was pulled from the game two batters later. He didn't even stay until the end of the game, and he gave only one interview that night, to George Plimpton, who strolled into the clubhouse and shared a cab back to the hotel with the pitcher.

Downing has embraced his role in history, attending dinners and other events honoring the moment. He's retired now, after nearly three decades as a broadcaster, mostly for the Dodgers.

Downing knows that for some, his 17-year All-Star career has been reduced to a trivia question. But he doesn't regret being the one who gave up number 715, and he was dismayed to hear pitchers express a desire to walk Barry Bonds rather than be linked with him forever when Bonds broke Aaron's record in 2007.

"If you don't want to give up home runs," Downing says, "don't pitch."

THE USHER

Officially known as an owner's-box usher for the Braves but unofficially regarded as the team's historian, Walter Banks might have been a history teacher in a past life.

He loves dates and places, pop culture and U.S. history, but his favorite facts involve the Braves. When Hank Aaron hit his 715th home run, he was wearing number 44, as was the pitcher who surrendered the hit, the Dodgers' Al Downing. And when Aaron was feted in April on the 40th anniversary of his achievement, he celebrated with a crowd of 47,144.

Banks, 75, has some impressive stats of his own. He began ushering for the Braves for $4 per game when the team moved to Atlanta in the spring of 1966. He also started working for the Falcons when they arrived that same fall, and he has never left either position. That's roughly 3,800 games with the Braves and at least 350 with the Falcons. He has also been an usher at Georgia Tech football and basketball games, but over the years he's kept one rule when it comes to scheduling conflicts: The Braves come first. In 2004 the Braves rewarded his loyalty by naming a suite after him.

On the night Aaron hit number 715, Banks was at his usual post in the owner's box, a few rows behind Aaron's family, Governor Jimmy Carter, Atlanta mayor Maynard Jackson and singer Pearl Bailey. Banks had seen plenty of Aaron's home runs over the years, and he knew immediately that the ball was gone. "I heard it before I saw it," he says. "You can tell by the sound of a home run like that."

Banks stayed on his feet for another 15 minutes, soaking in the moment. "I grew up in a segregated society," he says. "The only white person in my school district was the superintendent. [Aaron's record] was something to be proud of. He painted something 40 years ago, but in the heart of the people who were there, the paint is still fresh."

The man who sat in his car every afternoon 50 years ago and watched as construction workers erected Atlanta Stadium has followed the team to Turner Field, in the Summerhill neighborhood where he grew up. ("We used to get French's ice cream on that block for a nickel," he says. "Oh, you were in heaven!") And he plans to make the trip to continue working in the new park when it opens in 2017.

He has his dream job, after all: The history teacher has 50,000 potential students every day.

THE RELIEVER

Tom House vividly recalls feeling that Hank Aaron's record-breaking home run was going to drill him in the forehead if he didn't get his glove up. And he remembers presenting the ball to Aaron with a simple, "Here it is, Hammer." But the seconds in between, when he ran the ball from the bullpen to home plate? "I have no clue how I got there," he says. "The guys told me afterward that it was the fastest I'd ever run."

An average pitcher (29–23, 3.79 ERA) who appeared in 289 games over parts of eight seasons with the Braves, Red Sox and Mariners, House reached the apex of his career on April 8, 1974. Catching Aaron's hit got him onto a Trivial Pursuit card and, he recalls, into at least one third-grade reading handbook.

House retired from baseball in 1978 and has earned a bachelor's degree in management, a master's in counseling psychology, an MBA in marketing and a doctorate in performance psychology. Today he's one of the foremost experts in rotational sports—baseball, football, golf and tennis all share the same basic physiology because of the way the body swivels in competition—and he has helped athletes ranging from NFL quarterbacks (the Saints' Drew Brees trains with him in the off-season) to Little Leaguers. House devises workout and diet plans, and he uses a motion analysis lab, equipped with eight cameras that fire at 1,000 frames per second, to break down throwing and swinging mechanics. His National Pitching Association, which he cofounded in 2002, works with as many as 5,000 athletes a year.

House, now 67, has no plans to slow down. The man who has taken just one vacation in his life—a week in Mexico five years ago with his wife, Marie—finds relaxation harder than work. "I'll always be involved," he says. "I don't know what I'd do with downtime."

THE RADIO ANNOUNCER

Outside the den of Milo Hamilton's condo in Houston is the highlight of the 86-year-old sportscaster's collection: the Hank Aaron wall. Hamilton has both his scorecards, home and away, from the night of April 8, 1974; the framed article from that week's Sports Illustrated; a two-foot TV advertisement from the time featuring Aaron; and a photograph of Hamilton throwing his fist in the air as Aaron circled the bases.

Hamilton had all winter to plan what he'd say, but he let himself be spontaneous—with one exception: "I made a mental note not to say, 'Holy Toledo,'" which was Hamilton's catchphrase. "It was his day, not mine."

As is turned out, Aaron's will-it-get-out line drive left no room for a canned call. "I was a lucky son of a gun to be there and be the announcer," Hamilton says.

He spent four years with the Pirates and another four with the Cubs before becoming the Astros' main announcer, a role he kept for 28 years. He's now an adviser to owner Jim Crane. Hamilton has had chronic lymphocytic leukemia since 1974 and suffered his second heart attack in 2007. He's still in good spirits, though; Hamilton makes an appearance at Minute Maid Park during each home stand, and he has helped raise $45 million for 18 charities, including the Epilepsy Association.

Whenever he wants to look back, he can just walk down the hall of his home. One thing that's not there, though, is the Hallmark card he used to take with him to speaking engagements, the one that plays his call from that night: "It's gone! It's 715! There's a new home run champion of all time ... and it's Henry Aaron!"

Hamilton wore out the battery on that a long time ago.

THE PARTY CRASHER

Cliff Courtenay gets bored easily. Always has. But it wasn't boredom so much as bravado that led him to charge the field as a 17-year-old high school senior. He and his best friend, Britt Gaston, were on a college visit to Georgia, and Gaston's family got them tickets to the game. The friends were aware that Aaron had a chance to break the record that night but not so eager to see it happen that they got there on time.

"I think they made some announcements [like], If there's any funny business, people are going to jail," Courtenay says. "We must have missed those." When Aaron made contact, they leaped over the tarp and onto the field even before they realized the ball was gone. "That would've been embarrassing if it'd hit the wall," he says.

They caught up with Aaron as he rounded second and then headed for the leftfield stands. Quickly apprehended, they were taken to a stadium holding cell, charged with unlawfully interfering with the occupation of another and then transferred to an Atlanta jail. (Gaston and Courtenay were released the next morning with a warning to stay out of trouble for six months.)

Courtenay still seems bewildered by the attention he receives. Now an optometrist, he rarely volunteers information about his role that day; his wife, Lynn, didn't learn of it until they'd been dating for months and Courtenay's mother, Ruth, let it slip at dinner one night. But his patients bring it up. He's introduced as "that kid" at dinner parties, and a line once formed around him at a charity golf event. Courtenay and Gaston had grown apart over the years but reconnected when Gaston was diagnosed with cancer in 2009. They kept in close contact until Gaston died two years later.

Courtenay's still fighting boredom at 57, although he obeys the law now. Earlier this year he and Lynn rode motorcycles around an active volcano in Nicaragua; a few years ago he and his sons spent a day hiking through Costa Rica's wild Corcovado National Park. Running onto a field at a ballgame isn't close to the craziest thing he's ever done.

THE PLAY-BY-PLAY MAN

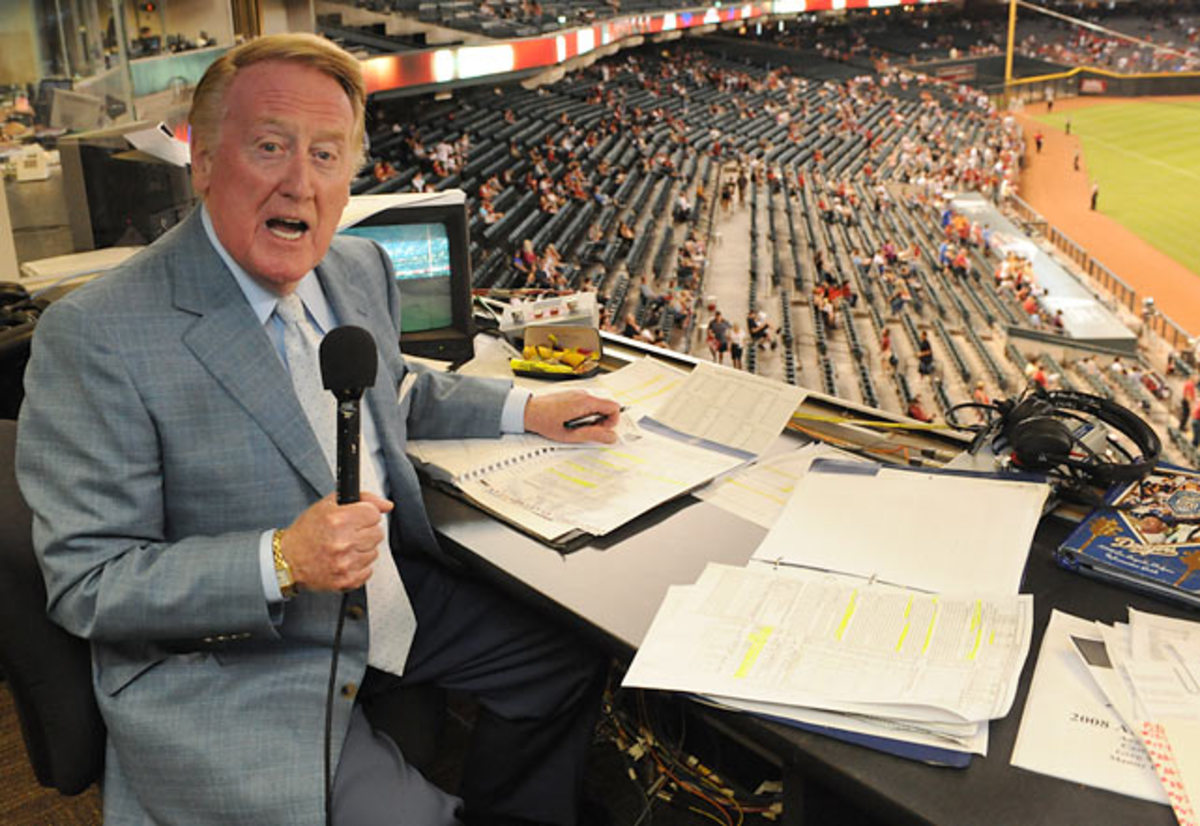

One of the greatest compliments Hall of Fame broadcaster Vin Scully has received was from a columnist who wrote that he “made his greatest contribution by saying nothing.”

Scully, who was calling the game for the Dodgers, has always tried to let crowd noise do the talking for him. So despite knowing that Aaron had a good chance to break the record, Scully didn’t prepare a call to use on number 715. He wanted what he said to come from the heart, and he wanted to be brief. After a quick “it is gone,” he took the headset off -- “the emotion was so great,” he says -- and walked to the back of the booth, where he stood, collecting himself, for almost a minute. When he returned to his chair he delivered his famous line, “What a marvelous moment for baseball; what a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia; what a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.”

Scully, a native New Yorker, hadn’t encountered much racism until he lived in an integrated barracks during his time in the Navy in the late 1940s, but he understood how much Aaron’s achievement meant.

“It was a major accomplishment,” he says. “It wasn’t just a baseball game.”

Scully, 86, is still broadcasting for the Dodgers, although he has cut back to just games in California and Arizona. He spends time with his 16 grandchildren and swims or plays nine holes of golf every once in a while. The memories of Aaron’s accomplishment don’t come back every day, but he has plenty of opportunities to remember.

“Every single time I see the number 44,” he says, “I think of Henry.”

THE CONFIDANT

They’ve fallen out of touch over the past decade or so, but there was a time when Pete Titus was Aaron’s closest friend. “We were friends for a long time,” says Aaron. When the slugger thinks about the people who had the most influence on his life, he says, “I have to put [Pete] right up there.”

Titus met Aaron during the slugger’s rookie season, in 1954. Aaron, then 20, had broken his ankle sliding into third base in a September game in Cincinnati. Titus, a 38-year-old postal worker who was introduced to Aaron through a cousin, felt bad for the young man. “He didn’t know anyone in this part of the country,” says Titus, 98. “He wasn’t nothing but a kid!”

So Titus visited him in the hospital, sneaking in food and recommending a barber for a shave and haircut. The two men remained close throughout Aaron’s career—Titus would drive Aaron around when the Braves were in town, and Aaron would invite Titus to stay at his house in Milwaukee for weeks at a time to fish—so it was no surprise when Titus found himself in the owner’s box, one row behind Pearl Bailey, on April 8, 1974. He had forgotten to bring an umbrella or raincoat, so he shielded himself from the drizzle with a program, but all was forgotten when Aaron turned on Downing’s pitch.

The rest of the night was a blur, punctuated by champagne (“I got out of the way,” Titus says) and fried chicken (“Some fellow from California had ordered a ton”).

Since then Titus has retired and gone on disability for a back injury he suffered catching a sack of mail. He watches sports on TV and spends time with his wife, Jackie, his three children, four grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Age has taken its toll—Titus doesn’t hear as well as he used to, his back aches, and he likes to say he’s been sick since 1998. “They didn’t think I’d live,” he says of his many ailments, “but I fooled them!”

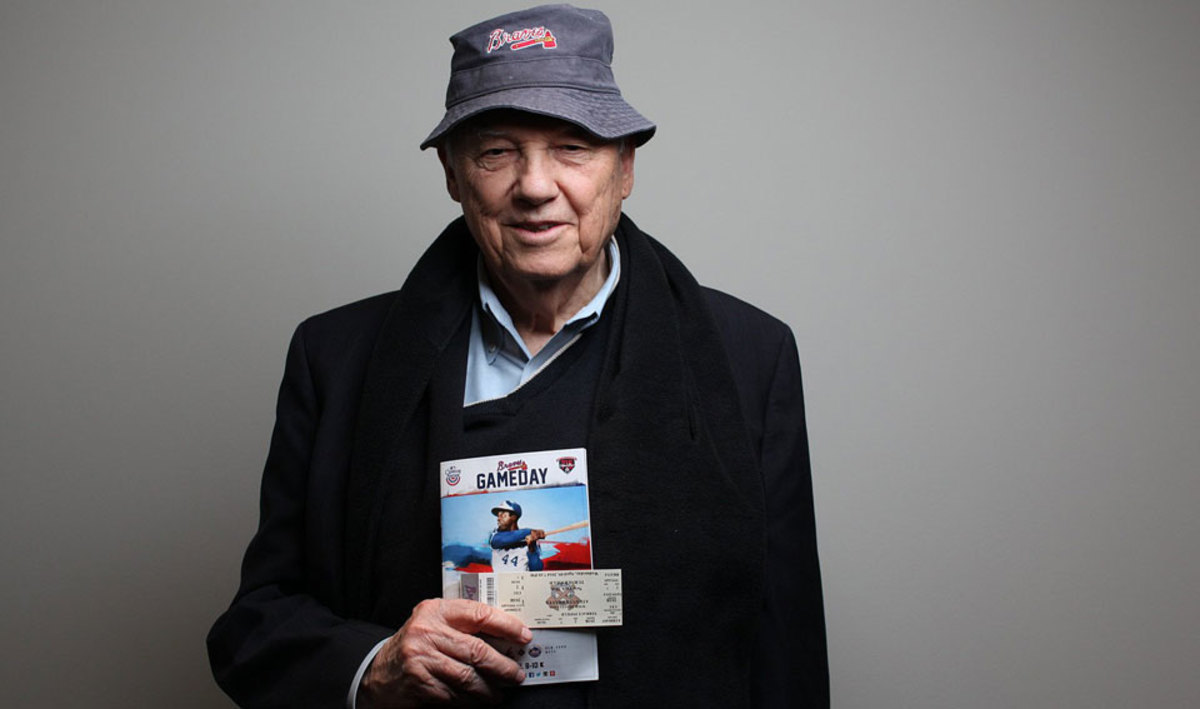

THE FAN

Where is T.W. Lord now? Pretty much where he was in 1974, even if his hair’s a little whiter and there’s a little less of it. His seats at Atlanta Stadium—he’s been a season-ticket holder since ’69—used to be behind home plate on the club level; now, at Turner Field, they’re on the same level but behind third base. But Lord, who was there with his wife, Hazel, on Aaron’s record-setting night, is proud that he has stayed close to home. “Friends come by to see me,” says Lord, 86, “people that have moved away, and I’m one of the few places they can come back and see the same name on the door.”

The owner of an insurance agency, Lord estimates that he has taken more than 400 children to games in 45 years, many of them kids of single parents and servicemen; often it’s the first baseball game they’ve attended. He makes sure to tell them Aaron’s story and drive home the lessons the slugger taught: work methodically over a long period, handle yourself well, let your efforts speak for you.

“I like for kids to understand that doing things the right way is important,” Lord says. “That’s why I want them to know about Hank.”

More Hank Aaron Stories From the SI Vault and SI.com:

• SI's Best Photos of Hank Aaron

•At 23, Hank Aaron Is Already the League's Best Right-Handed Hitter - Roy Terrell, 1957

• Henry Aaron May Be Getting Older, but He's Still Terrorizing Every Pitcher He Faces - Jack Mann, 1966

• Henry Raps One for History: Aaron Collects Hit No. 3,000 - William Leggett, 1970

• Despite Losing the Home Run Record, Hank Aaron Will Always Be "The People's King" - Tom Verducci, 2007

• Hank Aaron Transcended Baseball Like Few Ever Have—or Will - Tom Verducci, 2021