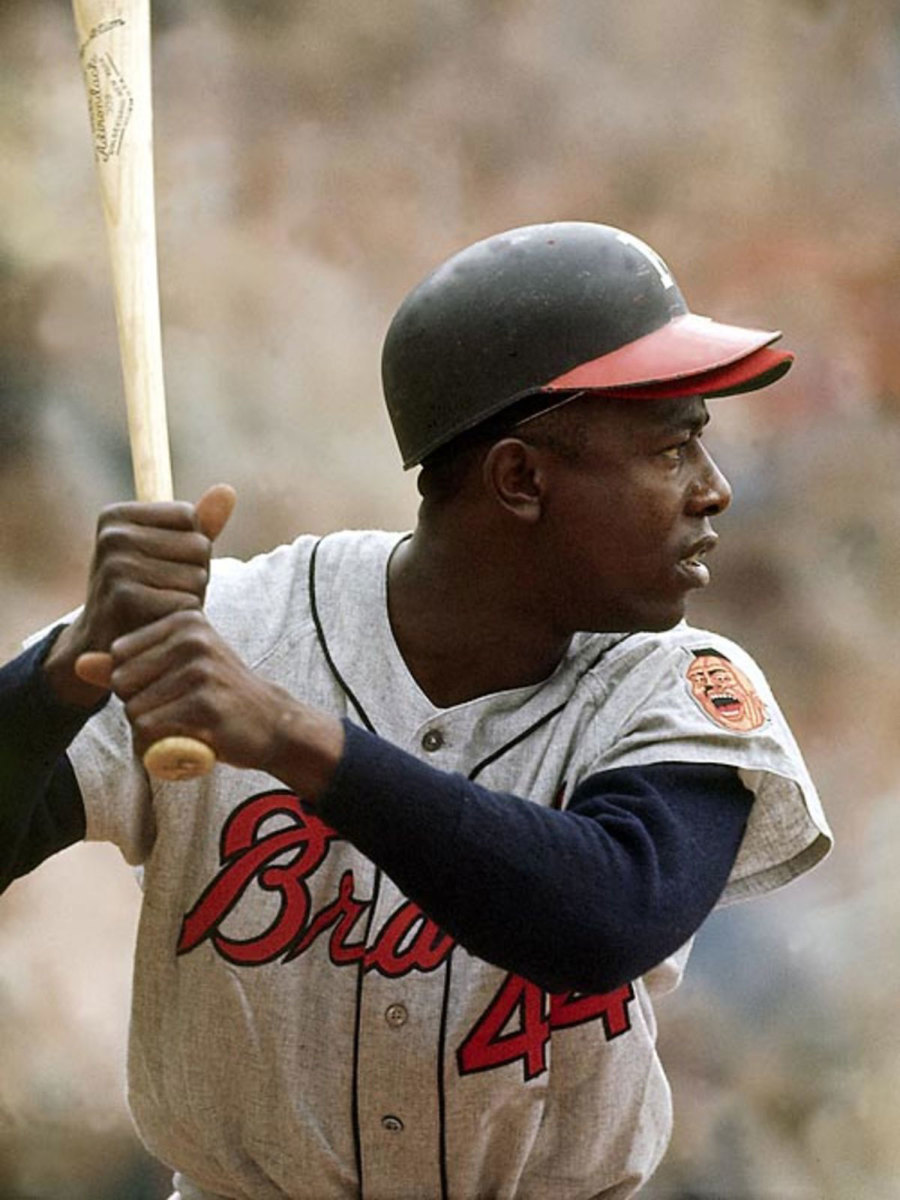

Hank Aaron Transcended Baseball Like Few Ever Have—or Will

Baseball is but a game. The consequences of wins and losses are trivial but for the ephemeral joy and sadness they leave on our soul like footprints in the sand. Those who play it well are renowned for their acumen at this very skill-specific endeavor. They are master craftsmen.

When age and illness take them, as they have so often in the past 12 months, we lose part of our youths and hold tight to the memories of how they could throw or hit a baseball.

Among the nearly 20,000 Major League Baseball players, Hank Aaron was one of the very few who transcended the game. He was bigger than baseball. He was a beacon for civil rights, of humility and of honest work ethic, all qualities we associate with America at its best, not just in some sporting venture. The Braves announced his death at age 86 on Friday.

Americans, not just baseball fans, owe a debt of gratitude to Hank Aaron. Yes, he was one of the best to ever play this game. Aaron died as the all-time home run leader, at least among all players who played the game fairly, which happens to be the very bedrock of sports. No one ever combined hitting for average and power over a more sustained period.

Aaron played 23 seasons. He came to the plate almost 14,000 times. He hit .305 with 755 home runs and 6,856 total bases—more than 700 total bases beyond everyone else. The gap between Aaron and No. 2 on the list, Stan Musial, is more than 12 miles worth of bases.

Yet the numbers, great as they are, do not tell the story of the impact of Aaron. He is the most important baseball player in the 74 years since Jackie Robinson stepped on the diamond at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn in 1947.

It was not just because Aaron broke the all-time home run record of Babe Ruth, as hallowed a record as there ever was. The importance of that happening was as obvious as black and white, or as Vin Scully said on air that night:

“What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol. And it is a great moment for all of us, and particularly for Henry Aaron.”

You wanted to add an “amen.”

It was also that Aaron conducted himself with hard work, class and humility, which is to say, he never stopped being himself, though racist America was there at his side trying to deter him.

Aaron was 40 years old in 1974 and playing his 21st major league season when he hit number 715. The chasing of Ruth over the previous few years so wore him down that when he stepped to a microphone immediately after hitting 715 the one summation that came to his lips was, “Thank God it’s over.”

Even when his glory days as a player were over, Aaron continued to dedicate himself to unselfishness, to helping others. He was a longtime executive with the Braves who grew the team’s minor league system. He established Chasing the Dream, a foundation that provides grants to children age nine to 12 to seek advance study in arts, music, dance and sports. He knew that age was the sweet spot of dreams and the drive to make them come true.

Last month I did one of the last interviews with Hank Aaron, on MLB Network. He looked great, especially when I asked him about Mickey Owen, the former catcher from Mississippi who was an early influence on Aaron.

Owen was Aaron’s manager in 1953 in winter ball in Puerto Rico, where the Braves wanted the infielder to learn how to play the outfield. Owen threw batting practice to him in the broiling heat for 14 consecutive days, each time with the same routine: 20 minutes hitting to right field, 20 minutes hitting to center field and 20 minutes to left field. And when they were done, Aaron would say to Owen, “I’d like to hit some more.” And Owen, then 37 years old, would throw some more.

“I would have to give him all the credit for my career,” Aaron said. “If not for him I don’t think I would have had that kind of career.”

I also asked Aaron to pick what made him proudest among his many accomplishments in baseball. He spoke eloquently about doing whatever he could as a batter to drive in a teammate from the bases. It was typical Aaron and it was beautiful. It wasn’t about him. It was about others.

Graciousness always was an Aaron hallmark, as much as the home runs.

As long as we live we can see in our mind’s eye that blunt swing of his—his powerful wrists wielding a bat as decisively as anybody who ever played this game. But today, as we say goodbye, all of us need to pause a moment, whether we are baseball fans or not, to say, “Thank you, Hank. Thank you for the gift you gave us of simply being Hank Aaron.”

More Hank Aaron Stories From the SI Vault and SI.com:

• SI's Best Photos of Hank Aaron

• At 23, Hank Aaron Is Already the League's Best Right-Handed Hitter - Roy Terrell, 1957

• Henry Aaron May Be Getting Older, but He's Still Terrorizing Every Pitcher He Faces - Jack Mann, 1966

• Henry Raps One for History: Aaron Collects Hit No. 3,000 - William Leggett, 1970

• Henry Aaron Gracefully Endured the Pressure of the Chase for 715 - Ron Fimrite, 1974

• Despite Losing the Home Run Record, Hank Aaron Will Always Be "The People's King" - Tom Verducci, 2007

• Where Are They Now: The People Behind Hank Aaron's Record 715th Home Run - Stephanie Apstein, 2014