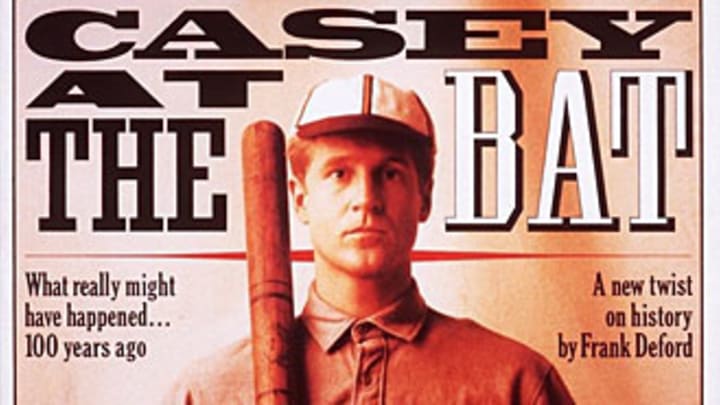

SI Vault: Huge Commotion in Mudville: A new twist on Casey at the Bat

This story is from the July 18, 1988 issue of SPORTS ILLUSTRATED.

AMAZING FINISH! Mighty Casey Fans • Slugger Didn't Arrive Till Seventh Inning • Beautiful, Evil Woman Seen In His Company

WOULDN'T YOU KNOW IT: Sun Still Shining Bright At Undisclosed U.S. Site

The porter scrambled to grab Richard K. Fox's bag when he arrived at New York's Grand Central that bright Thursday morning, May 31, a century ago. ''Boston'' was all Fox said, and the lucky fellow who had ended up with Fox's valise rushed ahead to the Pullman car. Fox was not handsome, with a mustache too bushy for his little head, a nose too big by half and cold, hooded eyes. But if he lacked the sleek looks of his animal namesake, he was every bit as clever. Like so many men who have succeeded in his profession -- Fox was an editor -- his strength lay in the deployment of better men's talents. On his cravat he wore a horseshoe pin of gold, studded with diamonds, open side down.

Fox settled in his seat and turned to the paper he'd brought onto the train. The Democrats, party of the incumbent president, Grover Cleveland, were about to convene in St. Louis and go through the formality of renominating their man. So the press, its priorities ever straight, was much more interested in what the President's young bride, the 23-year-old beauty, Frances Folsom, had worn the day before, Memorial Day. Quickly then, Fox skimmed through the pages until he came to the sports section. He was home now.

The sports pages in the '80s -- the 1880s -- had become a popular force. For the cranks (as baseball fans were so aptly known), there were the major-club box scores telegraphed from all over. There were even line scores from the burgeoning minor leagues. If Fox had looked closely, for example, he would have seen the scores from the Bay State League, which included this doubleheader result: Mudville 16, 8 -- Lynn 5, 2. And there were stories on boxing for the fancy (as the pugilistic world was called), horse racing, crew, tennis, cricket and many other games. No one was more responsible for this boom in sports reportage -- or for the profit derived from it -- than Fox, who had made his magazine, The National Police Gazette, a successful institution largely because of sports.

An item down near the bottom of the Tribune's sports page caught Fox's eye: CHAMPION RETURNS FROM EUROPE. John L. Sullivan, the report said, had arrived back in Boston last month and would be engaging in some stage exhibitions. ''Champion,'' Fox muttered, crumpling up the paper. ''Fat Mick lout.'' Sullivan was Fox's bete noir, for he was one man in sports Fox could not control, and everything he did to thwart the Boston Strong Boy only served to enhance Sullivan's reputation. It was Fox who had put up Paddy Ryan to fight Sullivan in '82, and Sullivan's victory established him as America's first great athletic hero.

Nonetheless, Sullivan would not do Fox's bidding, would not defend his title again. Instead, he went about making a fortune fighting in exhibitions -- ''My name is John L. Sullivan, and I can beat any sonofabitch in the house!'' he would bellow -- plus eating everything in the house, gulping bourbon from beer steins and whoring his time away. Frustrated, Fox made up a magnificent ''championship'' belt for the pretender, Jake Kilrain. So the whole damn city of Boston gave Sullivan an even grander bejeweled belt, and the Great John L. grew greater still.

The train pulled out of Grand Central, billowing smoke. Fox was on his way to Boston to personally goad -- somehow -- Sullivan into action. ''The Great John L.,'' he muttered. ''My arse.''

*****

About the time Fox's Pullman was passing through Bridgeport, Chester Drinkwater was escorting a handsome young couple into the amazing Cyclorama on Tremont Street in Boston's South End. The couple quickly became bug-eyed, for there before them -- all around them, really, in a circular vista 400 feet in circumference and 50 feet high -- was a painted re-creation of the Battle of Gettysburg. Timothy F.X. Casey didn't have to have it explained to him, either. He hadn't been born till '67, but his father had fought in the war, and an uncle had died at Antietam. Caseyknew his America.

And America was aboomin' -- the West filling, the cities bursting their seams, trolleys (some electric!) carrying the middle classes out into these new things called suburbs. Industry. Commerce. Science. Inventions. Wires were everywhere: Telegraph lines, telephone lines, electric lines. Yet America in '88 was still closer to Gettysburg than to the Ardennes, closer to Jeb Stuart than to Sergeant York, closer to Abraham Lincoln than to, uh, Babe Ruth.

Flossie Cleary had heard about Gettysburg, but because she hadn't crossed the ocean from Cork until '84, she was more impressed by the scope of the Cyclorama than by the scenes it depicted. So Casey took it upon himself to fill her in. Here's Little Round Top, there Culp's Hill. . . . Pickett's Charge is over. . . . Uh, oh. His hand went out, and it grazed against Flossie. Grazed. Lingered. Then it passed on, and Casey was telling Flossie about the cavalry, but she didn't hear a word. How many times had she whispered to Father O'Reilly in the confessional that she had sinned by hoping Timothy F.X. Casey might touch her . . . and now he had . . . and now they would be alone tonight. Chaperoned, of course, by Mr. Chester Drinkwater and his sister, but alone at beautiful, alluring Nantasket Beach. Different rooms in the hotel, of course. But still. . . . There was so much about this that left Flossie uneasy.

''Ah, Timothy, but exactly who might this Mr. Drinkwater be, and why would he be doing these lovely things for you?'' Flossie had asked when Casey first told her that he had this benefactor, this rich crank, who wanted to take them to Nantasket, in his own surrey, in his own sloop across Hingham Bay, put them up at the finest hotel, take them to the finest show.

''Flossie, would you be looking a gift horse in the mouth?'' Casey had replied, and a bit testily. ''Mr. Chester Drinkwater is not only a sporting man, but one of the most successful businessmen in Boston. He owns several trolley lines and the big amusement park in Newton.''

SI Vault: Too good to be true: How the 1994 season should have finished

Still, something stayed under Flossie's fair skin. On the occasion of that exchange, she and Timothy had been alone at the far end of the magnificent veranda at the house of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred L. Evans Jr., in the finest section of Mudville, where Flossie was employed as a downstairs maid. But she turned away from Casey, fretting. Things were moving too fast, and she was suspicious. Why, it had been quite enough, her falling in love with a ballist. In many quarters, ballists were dismissed as riffraff, which was fair enough, because that was what they were. Young men who played baseball, it was widely known, generally drank too much, gambled and specialized in separating young ladies from their virtue whenever the opportunity arose. Mostly, they consorted with other lowlifes, such as actors, dance hall girls, boodlers, flimflammers, second-story men, chippies, tarts and cracksmen. In fact, a great many ballists spent their off-seasons onstage or with a circus. Casey had joined the Mudville nine late in the '87 season and had met Flossie then, but he'd gone away soon enough, traveling with Barnum & Bailey. Mostly he worked as a roustabout for the side show, although he and another strong fellow would dress in leopard skins at show time and go onstage to try (unsuccessfully) to hoist the fat lady.

Casey frightened Flossie some because she loved him even though he was sort of mysterious. He didn't seem to have anyone close to him. He'd grown up in Baltimore but was orphaned, and his only sibling, his lefthanded twin sister, Kate, had married into a German family. He saw her only when the circus passed through Baltimore.

''It's this baseball craze, Flossie,'' Casey said, moving closer to her on the veranda. ''People just think it's a humdinger. Not just in Mudville. Why, did you know the Beaneaters paid $10,000 to the Chicagos just to get King Kelly to come play in Boston?''

Flossie gasped. Ten thousand dollars was more money than she expected to see in her lifetime. But something was happening in the '80s. Baseball was developing as a kind of adhesive that held together the evolving city and all its diverse types. It was said that any middling city that aspired to the big time needed three things: trolley lines, an opera house and a baseball team. ''What can I do, Flossie?'' Casey asked. ''I found out I could hit a horsehide, and now people love me for it.''

Mudville had gone bonkers over its nine that spring, and it was almost entirely because of Casey. The Evanses at first didn't want Flossie to have anything to do with a ballist, but after Mr. Evans left the bank early one day and went out to the Grounds to see Mudville whip Framingham 8-1 and Casey hit two triplets and a two-bagger, he let the young fellow come call on Flossie.

Casey had kept up the tattoo all spring. Why, not a single pitcher had yet struck him out. The baseballs didn't have much bounce in them, and the wheelman delivered from only 50 feet away, but Casey had such power that soon enough the local papers were calling him Mighty Casey. He was hitting .386, too, and grumpy old Cyrus Weatherly, the town miser who owned the team and the Mudville Grounds as well, was delighted to see that the ladies and gentlemen of the town were flocking to the East Side to watch the games. Even Mrs. Evans went to a game one afternoon.

Later that same day, Casey was on the Evans's veranda with Flossie when a rather ascetic young gentleman appeared. He explained that he had been directed to this address by someone at Casey's boardinghouse, so Mr. Evans steered him out to the veranda. ''Mr. Casey,'' the man said, ''my name is Jim Naismith, and I'm a student in Canada. I'm visiting at the training school over in Springfield, considering becoming what they call a physical education instructor there.''

''How do you do, sir,'' Casey said.

Naismith explained that word had reached Springfield that Casey had the finest natural swing in all the world. ''When the season is over,'' Naismith said, ''if they send you a rail ticket, would you come show the students your swing?''

''Gee, I don't know,'' Casey said, taken aback. ''The past two winters I traveled with the circus.'' '

'Oh, I see,'' Naismith said, clearly disappointed.

Casey glanced over at Flossie, then lowered his head. '' 'Course, I'm thinking maybe I won't be leaving Mudville this fall.'' Flossie's face turned crimson, and her heart bobbled.

“Well, now,'' Naismith said. ''I think you'd be interested in what they do in Springfield. Besides baseball in the spring, they have gymnastics and swimming and football in the fall.'' '

'What game do they play in the winter?'' Casey asked. '

'Nothing satisfactory, I'm afraid,'' Naismith said. ''But I'm going to work on that.''

Mr. Evans stepped up. ''You know, Timothy, you're a bright lad and good at sport. Maybe you ought to think about attending that school in Springfield after the season.''

Casey gulped. ''But that's like a college, Mr. Evans.''

“There's no law says a ballist can't go to college, is there, Mr. Naismith?'' And then he turned to Flossie. ''You wouldn't be bothered being married to a college man, would you, Flossie?''

Casey's jaw dropped. Flossie shrieked, ''Faith and begorra, sir,'' and dashed away. Mr. Evans threw an arm about Casey's shoulders, more as he would with a son than with some roisterous ballplayer. ''A real nice piece of dry goods,'' Mr. Evans said, winking at Casey, as they watched Flossie's trim ship sail away. ''A very nice piece of calico.''

Two weeks later, just before Memorial Day when Chester Drinkwater came by, Mr. Evans broughtCasey right into the parlor. After Flossie had served tea, Drinkwater came to the point. ''Mr. Evans, would it be possible for Flossie to come away with Mr. Casey and myself -- and my sister Maud, who'll chaperon, of course -- and go down to visit Nantasket Beach on Thursday?'' he asked.

That week the Mudvilles would exploit Memorial Day on Wednesday by playing a doubleheader. But then they'd be off until Saturday, so Caseycould get away to the beach. ''I've taken a keen liking to this young man,'' Drinkwater said, patting Casey on the knee. ''And the way baseball is taking hold, there may be a lot of cranks out there who'd love to deal with Timothy if he were a salesman for me.''

''Good business,'' said Mr. Evans.

“It'd sure be better than trying to lift that fat lady three times a day,'' Casey allowed.

Mr. Evans curled his mustache, thinking. ''Well, as long as she's chaperoned, and as long as she can make up the time, working her off- afternoons, I can't see why Flossie can't go to Nantasket.''

''Oh, thank you, sir,'' Casey whooped, and he bolted into the kitchen to tell Flossie the good news.

Mr. Evans turned back to his visitor. ''You know, Mr. Drinkwater, I can't tell you what a difference Casey has made to this town. Why he's not only changed the whole spirit of Mudville, but he's got people going over to that old East Side again. We haven't had any interest out there in years, but people go out to the Grounds, seeCasey wallop one, and . . . all of a sudden I've got a mortgage application on my desk for property out there. It's amazing what a team can do for a town. Something new in our modern society, I believe. Amazing. Had you ever thought about that?''

''No, I never had,'' Drinkwater said, lying through his teeth.

*****

Casey's Memorial Day performance was as fine as a hitter could have: eight for 12, two homers, 11 runs batted in. And what crowds! SRO! Waving American flags! The children hung from the trees, and all the bands from the Memorial Day parade reassembled at the Grounds, so grumpy old Cyrus Weatherly let them sit inside the centerfield fence -- for two bits a head -- and they played music all afternoon, adding to the holiday air.

The Mudvilles had never drawn so many people, and it was only May. Word of the Mighty Casey had even reached Boston, and because the Beaneaters were away on a western swing, a few cranks took the train out from the city. Ernest Thayer, Harvard '85, a frustrated poet who was resigned to working in one of the family's woolen mills, came in from Worcester. Flossie snuck away from the house late in the day and was at the Grounds for the eighth inning of the second game, in time to see Casey at the bat for the last time.

Hughie Barrows was on second and Johnny Flynn on first, and Casey knocked them both in with a ground rule double that rolled into a French horn in centerfield. The crowd went berserk. The score didn't mean anything now. In fact, baseball didn't matter. It was mostly a matter of pride. Not only did the people of Mudville have a hero, but they also were made heroic, touched by him.

However, all Flossie could see was that glorious, innocent face on second base: Casey, standing there, his cap off, waving to the throng, beaming. Practically all the players wore mustaches, and many of them bushy sideburns to boot. But Casey was apart. His face was as clean as it was bright, his eyes clear blue, his hair the color of a base path, his uniform happily dirty. Not poverty dirty or grubby dirty, but boyishly dirty, good dirty, thought Flossie. God, but Casey was clean. The tears poured down Flossie's cheeks. She was so in love, and maybe even better, she knew Casey loved her, too.

In the stands back of third base Thayer turned to a friend. ''You know,'' he said, ''there's that song about King Kelly.''

''You mean Slide, Kelly, Slide?''

''Right. And there's that barroom rhyme for John L.'' Thayer recited from memory:

His colors are the Stars and Stripes

He also wears the green.

And he's the greatest slugger that

The ring has ever seen.

No fighter in the world can beat Our true American:

The champion of all champions, John L. Sullivan!

''Pretty good memory, Ernest.'' ''Yeah, well this guy Casey deserves even more. He deserves an epic poem. I think I'll come back out here Saturday.''

On second base, Casey put his cap back on, and when he did, it was as if he caught a sunbeam in it and the rays wreathed his head in amber. Then he hitched up his pants and took a long lead off second.

2

Drinkwater escorted Flossie and Casey out of the Cyclorama. Her mind was still swimming at that marvel, the grandest thing she had ever seen. And now Drinkwater took her by the elbow and helped her into his rig, a magnificent surrey drawn by a pair of matching chestnuts. Why, Cinderella herself hadn't gone to the ball in anything finer, and Flossie only wished that Mr. Drinkwater wasn't along with them so that she could snuggle up next to Timothy -- and hang that anyone would see her carrying on so brazenly.

Flossie had been in the big city before, but this was different, looking from the surrey on the humanity scrambling about her. Boston had burst into a city of 400,000 people, easily double what it had been before the Civil War, and that didn't take into account the trolley suburbs. There were 231 miles of trolley lines now, carrying 85 million passengers every year -- all manner of souls: Chinese men with pigtails, Jews with long beards, Poles and Gypsies, sailors, beggars and urchins. Almost three quarters of the city was immigrant or first generation. Since '85, Boston had even had an Irish mayor. What else could hold this disjointed mass together but churches, saloons and baseball?

The surrey headed south, toward Quincy and the sloop that would take them across Hingham Bay. A trolley flashed across their path, the passengers hanging on, jaunty in the warm air. Tomorrow would be June! Flossie eyed the theaters, the shops, the department stores. In one window were fancy shawls on sale for $2.25. How Flossie wanted one, but there was no time and so much to see. Druggists on every corner, curing the ails of mankind. Signs and sandwich boards boasting of nostrums to correct OBESITY! OPIUM ADDICTION! THE ILL EFFECTS OF YOUTHFUL ERRORS! SUMMER DEBILITIES! There was Lydia Pinkham's famous vegetable compound for women, and Unrivalled Eureka Pills for Weak Men who suffered from early decay and lost manhood. The way things were going, what would doctors have left to cure in the 20th Century?

When they reached Dorchester the driver pulled off the main road, and Drinkwater explained that his sister had a touch of the vapors, it seemed, and so his niece Phoebe had graciously consented to fill in as a substitute chaperon. As soon as Drinkwater got down from the rig to go in the house and fetch her, Casey turned to Flossie and, taking her by the shoulders, looked into her face.

The Curious Case of Sidd Finch

Back in 1985, George Plimpton pulled off one of the all-time great April Fool's hoaxes, penning "The Curious Case of Sidd Finch" in the April 1 issue of SI. According to Plimpton, Finch was a mysterious rookie in training with the New York Mets. An eccentric character who only wore one shoe while pitching -- a ratty hiker's boat -- Finch allegedly threw the ball 168 mph. Despite the ridiculousness of the piece, many SI readers actually believed Finch existed. SI finally announced it was a hoax on April 15. Here are the pictures that accompanied the original SI story, as well as some that were never published.

How smooth it was. And in a world where so many people had disfiguring smallpox marks, Flossie's countenance seemed all the more polished, the rosy cheeks blushing, the green eyes enraptured, the tendrils of hair falling gently across her forehead. She knew he was going to embrace her then, kiss her right there in the surrey, in the sunlight. She also knew she wasn't going to stop him, and, indeed, when Casey didn't disappoint, when he took her in his arms and pressed his lips against hers, Flossie fell onto him and kissed him back with every bit as much fervor.

She absolutely astonished Casey, and so it was he who, finally, pulled back, wide-eyed. ''You're as beautiful as Frances Folsom herself,'' he gasped at last, paying her the ultimate compliment.

Flossie's mother had told her about boys like him. ''Am I now?''

''Oh yes, only I'm sure she doesn't kiss the President nearly so well,'' he smirked, making Flossie duck her head in proud embarrassment.

When she looked up, she knew Casey was going to try to kiss her again. To stop this madness, she put a finger to his lips. ''Tell me now, Timothy. What does Mr. Drinkwater seek from you?''

Casey glared at her. ''Dammit, Florence Cleary, I told you not to ask me that,'' he snapped. And he was so peeved at her, he sulked intermittently the rest of the trip, or at least until they put on their bathing costumes at Nantasket Beach and Casey got to see the flesh of Flossie's ankles.

*****

Richard Fox alighted at Boston's new Park Square Terminal that afternoon. What a ride: mile-a-minute, throttle out; a sumptuous meal; exquisite comfort and service. At the Parker House his suite was ready, but before going up, Fox asked the telephone traffic operator, the hello girl, to ring up the Third Base Saloon at 940 Columbus Avenue. After a moment a voice came on. ''Hello,'' it said.

''I'd like to talk to Mr. McGreevey,'' Fox said.

''This is Nuf Ced. Who's this?''

''This is Richard Fox . . . of the Police Gazette.''

There was a pause on the other end, and Michael T. McGreevey, known by one and all as Nuf Ced, clearly let fly into a spittoon. ''I don't know if I want to talk to ya.''

''Is Sullivan there?''

''Maybe he is. Maybe he isn't.''

''Look, Nuf Ced, I'm trying to make a lot of money for Sullivan. Tell 'im I came to Boston, and. . . .''

Pit-too. ''He ain't in Boston.''

“So, when's he get back?''

''Maybe tomorrow.'' Pit-too.

''O.K., you just tell Sullivan I'll be at your place tomorrow night.''

''Aye, I'll tell 'im.'' Pit-too. ''But I ain't sayin' Johnny'll like it, Fox. Nough said?'' said Nuf Ced.

*****

The reason Sullivan wasn't in Boston that Thursday was that he was the featured attraction at the Nantasket Beach show. Why should he defend his title against Jake Kilrain when he could make a king's ransom walking through exhibitions?

Drinkwater had the choicest seats for Flossie and Casey, himself and Phoebe, his niece. Truth to tell, Phoebe didn't look much like a chaperon. While she couldn't have been much older than Flossie, an aura of maturity hung on her no less than the men did. Many of those in the dining room seemed to know Drinkwater's niece as well as they knew Drinkwater. And he was a much recognized man. The Trolley King, everyone called him.

Flossie kept her eyes on Drinkwater, though not, perhaps, quite as much as Phoebe kept hers on Casey. And how raggedy Flossie felt beside Phoebe. Flossie was in her very best Sunday gingham, but it looked absolutely shabby compared with Phoebe's magnificent brown foulard gown, with white polka dots and a parasol to match. No wonder the men stared at her so. No wonder Casey did. Flossie was relieved when they could finally get over to the pavilion to see the show.

And what a performance it was! Though Flossie had believed that nothing could possibly compare to the Gettysburg Cyclorama, this surely was entertainment unrivaled. Here was the bill:

SI Vault podcast: Listen to the real (wink) story of Casey at the Bat

First, Gardini and Hamlet, blackface singers. Then the solemn dramatic recitations of Amos P. Lawrence, followed by John Mahoney, who performed a ''laughable trapeze,'' adroitly mixing humor and danger. Jessie Allyne came next, a brief novelty act. She let her magnificent hair down and down and down, until the golden tresses lay in great coiled rings at her feet. ''I seen something like that in a sideshow once,'' Casey said, ''but the lady in question wasn't nearly so grand.'' This was followed by the Authentic Monkey Orchestra, then Fairfax and Siegfried, human statues extraordinaire, and the ever-popular Willie Arnold, New England's favorite jig dancer.

Then it was time for the fisticuffs. First, before John L. came on, Patsey Kerrigan and George LaBlanche fought under the old ring rules, which the announcer explained meant ''anything but biting.'' Sullivan himself would have none of that. It was odd about John L. As utterly crude as he was -- almost barbaric in his personal habits -- he preferred gloves and the new Marquis of Queensberry rules, with scoring by timed rounds. Still, even the fashionable Nantasket crowd showed atavistic fascination as Kerrigan and LaBlanche clawed one another.

Drinkwater leaned across to Casey. ''Look about,'' he said. ''Look at your Miss Cleary and my, uh, niece. Look all around, and you'll espy that much of the applause here comes from the dainty gloved hands.'' Casey nodded. ''You see, Timothy, if women can favor a raw free-for-all as we've just seen, think how many of the lovelies would be attracted to a fine, clean sporting event like baseball'' -- Drinkwater lifted a finger -- ''particularly if it were played in a better part of town.''

Casey started to approve this wisdom, but he was stopped cold, for at that moment the Great John L. Sullivan entered the stage, a huge green robe slung loosely over his shoulders. Casey was aghast. The Boston Strong Boy was, in fact, the Boston Fat Boy. ''He's fat,'' Flossie said, with shock. ''Disgustingly fat,'' said Phoebe, with disgust.

The heavyweight champion of the world, 29 years old, looked closer to 39 and packed 243 pounds on his 5 ft. 10 1/2 in. frame. He was grotesquely flabby. His attendant, a spidery little sort named Smiler Pippen, laced on the champ's gloves, and that motion was enough to jiggle Sullivan's jowls and belly. John L. liked having Smiler around, for he was a self-professed druggist, who dispensed rubdowns and a favored potion, a so-called physic, which was made up of zinnia, salts and licorice. That was Sullivan's only concession to training.

He sauntered out to face one Francis Rooney, and to Casey's surprise, he had to admit that Sullivan could be remarkably nimble when he had to be -- for a second or two. But he was too much the walrus to maintain any pace, and though his blows obviously devastated poor Rooney, John L. was hardly a scintillating climax to the evening. Drinkwater and his guests left a bit disappointed.

Casey had hoped then for a stroll down the boardwalk, perhaps even a little trip along the beach, but Flossie was exhausted from the long day, and he had to settle for a chaste peck on her cheek. Then Phoebe conscientiously assumed her chaperon's mantle and ushered Flossie off to her room. ''A little nose paint?'' Drinkwater said to Casey, beckoning to the bar, where they took a table for brandy and cigars. '

'Well, Timothy, my boy, have you decided to accept my little proposition?'' Drinkwater asked after they'd lit up.

''I think so, but I'm not. . . .''

''I understand. You're a prudent young man,'' Drinkwater said, toasting him. ''So, let's run over it again. Now, you tell me you make. . . .''

''Eight hundred dollars for the season. . . .''

''. . . playing for Mudville.''

So Drinkwater took out his billfold and laid out eight $100 bills. Casey blinked.

''And if you stay with Mudville after this season, you'll be reserved,'' Drinkwater said. ''You understand? They'll own you. Reserve is just a pretty word for own. Bad enough that provision was put in for the major-club players, now it's in the minors, too. What is this? This is 1888. We fought a war over this 25 years ago.''

''Yes sir.'' The nerve of old Cyrus Weatherly and those other owners.

''Now, I'm prepared to pay you three thousand dollars'' -- to spell things out, Drinkwater laid down two more centuries and a pair of $1,000 bills -- ''to leave Mudville.''

Casey gasped.

''Take the summer off,'' Drinkwater went on. ''Next season, I'll help you sign with anyone.''

''The Beaneaters,'' said Casey.

''Why not, Timothy, my boy?''

Casey's eyes twinkled.

''And finally, an extra $500 to seal the bargain,'' Drinkwater said, and he laid out a $500 bill. ''And I'll throw in a beautiful new gown for that young lady of yours. You get this right now'' -- he slid the $500 closer to Casey -- ''and the rest after five more games. Only you're not to get a single hit in any of those games. I don't want you just disappearing. That'd be too curious. But if all of a sudden you start striking out, it'll look like something went wrong with Mighty Casey. People will think he went lame, lost his ginger. Then you take the $3,000 and drop out of sight. Only, when you materialize next year, you're in the National League.''

Casey's hand itched to reach out and take the $500, but, after hesitating, he took up the brandy glass instead. Casey was no dummy. ''Mr. Drinkwater, I'm no dummy,'' he said. ''There must be a reason you'd pay me all this.''

''Of course there is, my boy. But there's an expression going around: What you don't know won't hurt you. You just have my word as a sporting man that it's not illegal. What do you say?''

Casey paused a moment. ''Let me sleep on it.''

''Very wise, my boy,'' Drinkwater said, chuckling. ''Yes indeed, you sleep on it tonight. Heh, heh.''

*****

Casey entered his room. From out of the shadows Phoebe came toward him, letting her long sable hair tumble down to the brown foulard dress with the white polka dots. Only then did Casey realize that she didn't have the brown foulard dress with the white polka dots on anymore. ''I thought you'd never come up, Timothy,'' Phoebe said with a sigh.

Later, when Phoebe had dressed, she pulled a $500 bill out of her purse and left it on the bedside table. ''So, we're in business . . . with my uncle,'' she said. And Casey smiled and nodded.

He felt rotten, dirty and deceitful, and wondered when he could see her again.

*****

3

Late the next afternoon, back in Boston, Casey and Flossie walked along the Charles. They'd come up from Nantasket with Phoebe and Drinkwater and had checked into the Parker House, where they planned to spend the night before heading out to Mudville the next morning for the big game. It was a glorious day -- the emerald grass, the sculls and sails upon the water, the promenading swells from the Back Bay – but Casey knew that none of the ladies of Boston was as gorgeous as his Flossie.

Drinkwater had arranged for a new outfit to be waiting for Flossie at the hotel: Blue-and-white-striped silk it was, and her splendid figure filled it like one of those sails on the Charles. The dress had wide cuffs and a deep collar of white linen. And there was a leghorn straw sailor with a blue band and flowing white ribbon. Parasol to match. ''You're the loveliest, Flossie,'' Casey said. ''There's not a man on the esplanade who's not trying to catch your eye.''

''Pshaw. No one would buck a gentleman so pleasing to the eye as you,'' Flossie said, giving a little flip to her parasol. She was learning quickly how much more effectively she could flirt when she was well dressed. ''But, ah, I must be watching you, I must.''

''Oh, how's that?''

''That Phoebe woman. I truly don't believe she's Mr. Drinkwater's niece, but I do believe she'd like to seduce you, Timothy Casey.''

Casey threw his hands to his head and rolled his eyes. ''Flossie, that is the most ridiculous thing I've ever heard,'' he said. He shook his head one more time for effect and stared out at the river.

Whew, he thought, I nipped that in the bud.

Ohhh, thought Flossie, she's seduced him already.

She turned to face him squarely. ''You made your deal with Mr. Drinkwater, didn't you now?''

''Sure enough,'' Casey said, beaming. He pulled out the $500 bill, brandishing it and telling her all the benign details of the arrangement. But Flossie turned away.

''I love you, Timothy Casey. I surely do,'' she said. ''But I can't be marryin' you if you're involved in. . . .''

''But there's nothing illegal. I told. . . .''

''Well, let me tell you,'' Flossie snapped, whirling around, her green eyes searing. ''Mudville loves you, Mr. Casey. Why, I've heard Mr. Evans tell that you're bringin' the whole East Side back to life, you are. Can't you see what Mr. Drinkwater and that wicked lady want? They want to build a trolley line way out in the opposite direction from Mudville, practically to Devonbury, to move everything out there. Can't you understand what he'll do to Mudville?''

''Flossie, it's just good old American business know-how.''

Flossie stamped her parasol on the ground as if it were a shillelagh. ''Timothy Casey, would you be a dumb Mick? Can't you see? I'll bet Mr. Drinkwater's bought every bit of real estate out there. I'll wager he's going to build an amusement park, a . . . another baseball grounds. Can't you see that? You breathed life back into our little town, and now he's stealing you from us. That's worse than breakin' any law. Ah, that's breakin' th' spirit.''

''But. . . .'' Casey began to protest, and made the mistake of holding up the $500 bill. When he did, Flossie slapped it away, and he had to scramble after it. By the time he had retrieved the money, his Flossie was weaving in and out among the strollers, disappearing.

*****

When Casey got back to the Parker House, a package was waiting for him at the bell stand. He opened it, and there was Flossie's new dress. A note was pinned to it. It said, ''Dear Timothy, I'm sorry, but I cannot accept this or what you are doing with yourself. Do not come calling on me again. Very truly yours, Florence M. Cleary.''

Casey crumpled up the note in anger and rushed over to the front desk with the open package in his hands. A well-dressed man with a horseshoe pin on his cravat was standing there. He looked over Casey, looked over the dress. ''Woman trouble?'' he asked, but sympathetically.

Casey ignored him. To the clerk, he said, ''What room is Miss Phoebe Alexander in, please?''

''Seven-eighteen.''

Casey grabbed a pen, dashed off a note and called for a bellboy.

''I'm sorry,'' said the man with the horseshoe pin. ''I didn't mean to bother you, but you look like a boxer.''

''A fighter? Not me. I'm a ballist.''

''Oh, well, I'm sorry. It's just that I'm a fancy man.'' He put out his hand. ''Richard Fox, of The Police Gazette.''

''No fooling,'' Casey said, licking the envelope. ''Gee, I read the Gazette every month.''

He handed the bellboy the note and a half a dime. ''Seven-eighteen. And wait for the lady's reply.''

Then he stuck out his hand to Fox. ''I'm Timothy Casey, rightfielder on the Mudville nine.''

''Well, well,'' said Fox. ''I've got a bit of business in a while, but would you join me for some nose paint while I'm waiting?''

Casey looked at Fox. The Police Gazette. He looked at the bellboy waiting for the elevator, and he thought of Phoebe's hair cascading over her bare shoulders. He looked back at Fox. He saw Flossie's eyes. Back to the bellboy. He was just getting on the elevator. He saw all of Flossie. He saw Flossie's love and his own shame -- and in the split second it takes a horsehide to travel 50 feet to the bat, Casey dashed to the elevator and yanked the little bellboy out through the closing doors. ''Keep the half a dime, but gimme the note back,'' he said, and then, smiling, he hustled back over to Fox.

*****

Nobody had come up with the term sports bar in 1888, but if they had, the Third Base Saloon, Michael T. McGreevey, Prop., would surely have been recognized as the first such institution. Athletic souvenirs -- especially baseball gear -- cluttered the place, barely leaving room for the cranks who jammed in, particularly after Beaneater games at the South End Grounds nearby. ''I call it Third Base 'cause it's the last place you stop before you steal home,'' McGreevey would growl. '' 'Nough said?''

McGreevey was stout and tiny, a terrier among men, with a handlebar mustache, and while he had been baptized Michael Thomas, he was always called Nuf Ced. Fox explained this to Casey as they entered the Third Base Saloon and trod across the large mosaic on the floor that spelled out NUF CED. ''He's here, Johnny,'' Nuf Ced roared from behind the bar.

''Who's here?'' The great booming voice of John L. Sullivan answered from somewhere in the back. ''Anybody important?''

''No, just Richard Fox, the chucklehead who gave a championship belt to Jake Kilrain.'' Pit-too.

Fox smiled facetiously, tipped his hat to Nuf Ced and bade Caseyjoin him at a table. They ordered beers, and Fox explained they would just have to wait for Sullivan. Sure enough, it was an hour or more before Sullivan, with a big tankard of ale in one hand, appeared. He was accompanied by Smiler Pippen on the one side and by his floozy of the evening, Rosie, on the other. ''All right, Fox, what is it you're wantin'?'' John L. snarled, and Nuf Ced, taking his cue, came over to the table to stand between the two men.

''I just want you to fight Kilrain, Johnny.''

''For you, Fox? I ain't no henhouse to let a Fox into,'' he said, and everyone in the Third Base Saloon roared.

''Then don't do it for me,'' Fox went on. ''Just fight him. That's what all the fancy wants. Or are you too fat, Johnny? Too old?''

''Why you goddamn -- '' said Sullivan, reaching down to grab Fox. John L. had taken the bait. Fox figured that Nuf Ced would jump in, and he did, but Fox didn't figure that, faster still, his new friend Casey would spring to his feet. Casey shoved Sullivan. The ale went flying, and the big fellow needed help from Smiler and Rosie before he could regain his balance. He glared at Casey, at this white-faced, clean-shaven bumpkin. ''And who the hell are you, sonny?'' Sullivan shouted.

Casey didn't back down. Indeed, he leaned forward a little, never taking his eyes off Sullivan. ''My name is Timothy F.X. Casey, and I can beat any sonofabitch in the house.''

The Third Base Saloon fell into a hush. ''Is he serious?'' Sullivan said at last.

''Are you serious?'' Nuf Ced said. Pit-too.

Fox pulled at Casey's sleeve. ''You're not serious, are you?'' he asked.

''Sure, for a price. What are the odds on me?''

''A thousand to one,'' Nuf Ced said. Pit-too.

''I'll take anything he wants at 20 to 1,'' Sullivan snapped.

Immediately, Casey yanked the $500 bill out of his pocket and waved it. ''You're on, John L.,'' he said. ''For this.'' The crowd gasped as one.

Nuf Ced closed the bar, and the entire ensemble traipsed over to the South End Grounds, where they staked out a ring between the pitcher's box and first base. There was a good moon and enough city light.

''You sure you wanna go through with this, Casey?'' Fox asked, helping him off with his coat. ''I had Paddy Ryan fight him in '82, and he said it was like a telegraph pole went through him the first time Sullivan hit him.''

''That was '82. I seen Sullivan last night,'' Casey said. ''He's fat as a hog, and he's drunk a lotta ale tonight. Besides, my girl left me, and I'm mean.''

''Up to scratch,'' Nuf Ced cried out, and the two fighters stepped forward to a line Nuf Ced had drawn in the dirt. The spectators stood about in a square, already screaming.

''Four rounds,'' Nuf Ced said. Pit-too. ''No biting, scratching, gouging, tripping or wrestling.''

Both men nodded. Sullivan spit on his hands. Nuf Ced raised his arm. Sullivan knew what to expect. But Casey had figured it out, too. He didn't even look at Sullivan. He kept his eyes on Nuf Ced, and the instant his arm moved, Casey ducked. Good thing. The air was shattered by the force of John L.'s blow.

Casey came up, in one motion banging his right to the big fellow's big belly, and then his left. By the time Casey was standing full up, Sullivan was holding his stomach. So Casey stepped in and, with all his might, pounded his right to the champion's meaty face. And with that, barely 10 seconds into the fight, Casey had hit a home run. The Great John L. buckled and fell.

The Mantle Of The Babe: Mickey Mantle eyes Babe Ruth's home run record

The crowd fell into utter silence, shocked. Blood trickled from the corner & of Sullivan's mouth, but he wouldn't dab at it, any more than Casey would grab his throbbing knuckles. Instead, the two men just glared at each other, until finally Sullivan began to rise on the count of eight. He got up like a bull elephant, slowly at first, but once he had lifted his great bulk off the ground and leaned forward, he possessed a momentum that no sleek creature could achieve. He pounded the few steps toward Casey. It would have been easy for Casey to step aside, except he was backed up against the crowd -- John L.' s crowd -- and the loyal spectators blocked Casey's movement. He tried to duck, but as he'd seen in Nantasket, Sullivan, for all his corpulence, still had some agility. John L. caught Casey flush with an uppercut. Casey staggered back, his face exploding, his brains rattling about.

He wanted to go down and regroup, but not only did the spectators block his fall, they also propped Casey up -- and then bounced him back toward Sullivan. Casey was a helpless target, and he could see, in his daze, John L. winding up for the knockout.

Then, inexplicably, just like that, Sullivan dropped his dukes and idly watched Casey fly past him, still propelled by the push from the crowd. Sullivan put his hands on his hips and glared at the spectators.

''John L. Sullivan doesn't need any help when he's in the ring,'' he bellowed. The offenders shrank back.

His rebuke complete, Sullivan turned to finish off Casey. But the moment was lost; Casey had shaken his head clear. When John L. swung, Casey hopped aside, as if he were getting away from a high inside pitch, and with everything left in him, he ducked and came up throwing, like a shortstop pegging to first. Whoosh. Into the champion's soft underbelly. Sullivan gasped. His chin was wide open, but Casey went for the tummy again. And again. The champion doubled over, and only then did Casey aim his left hand -- the one that still had its knuckles intact -- for Sullivan's chin. Bam! John L. crumpled to his knees and then pitched forward, spitting out blood and ale, spilling his beans.

''Start the goddam count, Nuf Ced!'' Fox screamed.

Sullivan peeked up. He didn't know how Casey's hands ached. So, he just waved Nuf Ced away and sank back onto the infield grass, into his own blood and guts. The Great John L. was beaten. ''Congratulations, sonny,'' he said. ''Now you can tell the whole world you was the first sonuvab. . . . You was the first man ever to beat the Great John L.''

''Gimme my $10,000, and I'll never tell a soul on God's green earth,'' Casey said.

''Don't matter none. That viper Fox'll put it in the Gazette.''

Fox stepped forward to Sullivan. ''Not if you fight Kilrain, I won't, Johnny,'' he said.

''Yeah now?'' said Sullivan, the possibilities dawning on him, and he looked all around at the crowd. ''Any sonuvabitch here see John L. Sullivan get beat tonight?''

There was silence for another moment as the crowd looked at one another. Finally, Nuf Ced spit and spoke up: ''No, indeed, not me.'' And then the others cried out, ''Not these eyes!'' ''No, no, no.'' ''I didn't see nuthin'.''

Sullivan nodded. ''All right, Fox, I'll fight your boy.''

''Bare-knuckle.''

''Yeah, bare-knuckle. One last time.''

Casey started to walk away. ''Get me my money, Fox,'' he called out, and the onlookers stepped aside for him, standing back in awe, afraid even to whisper in the presence of, let alone get in the way of, the man who beat John L.

Suddenly, Fox ran after Casey and caught him near home plate. He took his diamond-studded gold horseshoe off and pinned it on Casey's shirt. ''Thanks'' was all Fox said.

Casey took the pin off. ''You never worked a circus, did you, Fox?'' he asked.

''No.''

Casey put the pin back on his shirt, but he fixed it with the open end of the horseshoe up. ''You never hang a horseshoe down,'' said Casey. ''Anybody on a circus knows that. Hang it down, all the good luck will run out.''

Fox nodded and smiled. ''No wonder you never beat John L. before,'' Casey said.

*****

4

Flossie was hanging the washing on the clothesline the next afternoon when Casey came tearing up to her, his face all bruised. ''Timothy, what in heaven's name. . . .''

''I haven't got time,'' he said. ''I'm already late for the game, and I gotta see Drinkwater, too.''

She gritted her teeth at the mere mention of that name, but Casey only reached out and pinned the horseshoe pin above her breast. ''We can pluck the diamonds out and make a proper engagement ring,'' he said, and with that he dashed off to the ball yard. Flossie unfastened the pin to look it over. Why, it obviously cost even more than the silk dress. How much more money was Drinkwater paying him now? And for what? Furious, Flossie pinned the horseshoe back on, and even though only half the washing had gone up on the line, she rushed off.

There had never been a larger crowd for a baseball game in Mudville. Had everybody in town skipped work? Had every kid robbed his piggy bank? Grumpy old Cyrus Weatherly had stuck the overflow behind ropes in centerfield. Ernest Thayer had arrived in time to get a ticket, but the crowd spilled over into the aisles, and he had a hard time seeing some of the action.

But where was Casey? Mighty Casey? Nobody knew. Only Drinkwater, sitting in his box by the Mudville bench, beamed.

Willie Flaherty, the Mudville manager, put McGillicuddy in for Casey, but the Mudvilles were at sea without their star, and the Lynns built a 4-2 lead. Then, just as Lynn made out in the seventh, here came Casey sauntering onto the diamond. The people roared and screamed his name, everyone standing and stretching for just a glance. Weatherly glowered at his tardy slugger. Drinkwater nodded his head and winked at Casey as he jogged to the bench. The kid has a real sense of theater, Drinkwater mused. To show up like this and then strike out -- an even greater disappointment for the gullible locals. Casey went right to the manager. ''I'm ready, Willie,'' he said.

Jimmy Blake was leading off in the seventh, so McGillicuddy was on deck -- Casey's spot. But Flaherty waved the Mudville star away. ''Sit down, Mr. Casey,'' he said. ''I play the guys who are here when the game starts.''

While the crowd booed, poor McGillicuddy batted -- bumping a little dribbler back to the wheelman. Three up and three down. And the same in the Mudville eighth. However, when Barry O'Connor, the Mudville pitcher, retired the Lynns in order in the ninth inning, he came out of the pitcher's box and headed straight for Flaherty, to beseech him to let Casey have his licks. Flaherty spit and then said, ''O.K., Barry, if we get to McGillicuddy's spot, I'll give him a swing.''

But the elation on the Mudville bench was short-lived because Cooney grounded out and Barrows topped a ball to first. ''I've never seen such a sickly silence,'' Thayer said to the fellow next to him.

''Still,'' the other gentleman said, ''I'd put up even money if Casey could get at the bat.''

The pitcher for the Lynns was a wiry little guy named Kenny Landis, who was a law student pitching under the nom de baseball of Walt Mueller. In his heavy flannel, he was sweating copiously as he peered in for the final out against Johnny Flynn. Landis tried to dry his pitching hand on his trousers, but they $ were almost soaked through with sweat. With his wet fingers, and his being tired, too, he hung an in-shoot, and Flynn knocked it cleanly up the middle. That brought Blake to the plate, and the Mudville Grounds exploded, but even Blake knew it wasn't for him. No, the roar was for who would come after Blake: Casey, the Mighty Casey, was moving up on deck.

Casey detoured on the way, going over to speak to Drinkwater. Flossie had found her way into the Grounds by now and had worked her way to the first row in the centerfield overflow. When she saw Casey consorting with Drinkwater again -- and right out in the open! -- she slammed her arms folded across her chest and cursed the best way she knew how.

Blake was an old-timer, cagey when he was sober, and he decided to rip into the kid pitcher's first pitch. He rifled it down the leftfield line, and when the dust was settled, he was standing on second base and Flynn on third.

Here came Casey. Poor Landis could hardly see through his sweat. But, he thought, Casey probably wants to see what kind of stuff I have, so he'll be taking. Good thinking: Casey let a waist-high fastball go by. ''Strike one,'' said the umpire. Flossie wrung her hands and prayed that Casey would find his conscience and hit the ball.

Landis came back with an out-drop, but Casey thought it was off the plate. The umpire, standing behind the pitcher, saw it nick the corner. ''Strike two,'' he said.

But the Mudvilles weren't worried. Casey had seen the kid's repertoire, and he was a celebrated two-strike hitter. The cranks were all on their feet, hollering, and Thayer, even on tiptoes, had to hop this way and that to follow the action. In fact, he missed it when Casey, staring out at the pitcher, spotted Flossie directly behind him, watching from straightaway center, standing out against the crowd in her maid's uniform. For just a moment Casey smiled at her, and then something came over him. Before he knew it, he had raised his bat, pointing it toward center, calling a home run right over his dear Flossie's head. The crowd roared.

''What was that? What was that?'' Thayer cried.

''I couldn't see, either,'' the guy next to him said.

Then the crowd parted a little, and Thayer was able to watch as Casey clenched his teeth and pounded his bat. Landis sweated even more. He would have gone to the resin bag, only there weren't any resin bags yet, so he rubbed his hand on his clothes, on his cap, his socks, his hair, his mustache. Then he reared back and let the ball go. Casey saw it all the way. The pitch didn't have a thing on it. He began his swing, poised, evenly, perfectly. . . .

Casey missed it by a country mile.

Mudville blinked. Mudville couldn't believe it. Flossie could. Flossie cried. Casey had gone on the take. There was no joy in Mudville.

Only . . . wait. The pitch had darted down, and it went under the catcher's glove. It began to roll to the backstop, and here came Flynn, already bearing down on the plate. Casey began to run for first. The catcher got to the ball, picked it up, dropped it, picked it up again, and there went the throw, soaring over the first baseman's head by five feet. Flynn scored. It was 4-3. And here came old Blake right behind. Tie score. Four-up. And Casey was on his way to second. He rounded the bag, and the rightfielder picked up the horsehide down the line and threw behind Casey, to nail him as he tried to scramble back to second. Only Casey saw where the throw was going, and he put his head down and kept on for third. The second-sacker took the throw, a good one, whirled and whipped it to third. It bounced in the dirt as Casey slid, and ricocheted off the third baseman's shoulder and down the leftfield line. Casey scrambled to his feet and was on his way home. The third baseman tore back, picked up the ball and fired it to the plate. Casey slid. The catcher took the ball and slapped it on him. ''Safe,'' the umpire said.

''Curses,'' Chester Drinkwater muttered.

There was joy in Mudville. The crowd poured onto the field and lifted Casey to its shoulders. He had struck out, but they hoisted him up and began to parade him around.

Casey saw Flossie out in center. The rest of the crowd had run in, and she was just standing there, all alone, the tears flowing down her cheeks. ''Let me down, let me down!'' Casey cried, and he fought his way off the shoulders to the ground and ran to her, ran as fast as he could, ran even faster than he had when he'd circled the bases.

Only, when he grabbed her, Flossie said, ''I hate you, Timothy Casey.''

''Listen to me, Flossie. Dammit, listen to me! I tried. I tried! I tried! He just struck me out.''

''I don't believe you,'' she said, and she twisted away from him.

''But you must,'' Casey screamed. ''It happens. Somewhere, someday, somebody's even gonna beat John L. Sullivan. It happens.''

''You cheated us all!'' Flossie cried.

Before he could go on, Casey felt a tap on his shoulder. All the Lynn players were filing past, leaving the Grounds, and there was Landis, the pitcher. ''Mr. Casey, no matter what happened, I just want you to know it was an honor facing you,'' he said. ''And I want you to know that that last pitch was the best one I ever hurled in all my life. I don't even know how I did it.''

''It was sure some pitch,'' Casey said. ''If you can throw that pitch again, you can strike out King Kelly hisself.''

Only Landis never did throw that pitch again. He tried. He tried holding the ball this way and that, releasing it here and there, firing it fast and slow. But all he did was give himself a sore arm and hurry himself into the judiciary. Landis didn't realize he'd mixed his sweat with his mustache wax and thrown the first spitball. Because he didn't know that, he would never do it again, and it was 14 more years before somebody invented the spitball.

Casey yanked Landis over to Flossie. ''Tell her, tell her,'' he screamed at Landis.

''Well, ma'am'' said Landis, ''like I just said, that was the best pitch I ever threw.''

''You hear that, Flossie?'' said Casey. ''He just struck me out. He was just better'n me.''

He chased after her some more, but she wasn't convinced. ''I don't believe you,'' she said. ''I even saw you talking to Drinkwater just before you went to the bat.''

''That was because I told him I left his $500 and the silk dress with Phoebe at the Parker House, because you were right and I don't want nothing to do with his deal.'' He grabbed Flossie by her cheeks and held her face before his. ''You hear me, Flossie? I love you! I love you!''

She appeared to be considering this, so Casey pulled out all the stops. He sank to one knee, took her hands and said, ''Florence Cleary, will you do me the honor of being my wife?''

Flossie believed him. ''Yes, I will,'' she said.

Casey jumped to his feet and kissed her, and all the cranks who were standing around watching began to cheer. Then Casey said, ''It's a good thing for you that you said that, because I'm also a rich man now. I got ten $1,000 bills in my shoes.''

''What?''

''I'll tell you all about it sometime, but right now. . . .'' He reached over and took off the horseshoe pin, because he'd just noticed that Flossie had put it back on upside down. ''Don't ever wear a horseshoe pointing down, because then all the luck will run out of it,'' he said, and he pinned it back on her, the right way.

Then he put his arm around her, and they walked off together, toward the sunset, as a matter of fact. ''You mean if I'd worn the pin right you'd have hit a home run over my head, the way you pointed?'' Flossie said.

''Nah, nobody could've hit that pitch,'' said Casey. ''You gotta understand, darling -- in baseball, even the best ballists only get a hit one out of every three times up.''

*****

EPILOGUE

Here is what happened to the principals after June 2, 1888:

John L. Sullivan kept his word to Richard Fox and, on July 8, 1889, fought Jake Kilrain, successfully defending his championship in 75 rounds. It was the last bare-knuckle title bout ever fought.

Richard Fox remained a pillar of popular journalism, and The National Police Gazette prospered until 1977. Fox's mix of sex, sport and crime serves many well even today, especially if you add weather.

Nuf Ced McGreevey continued to preside over his sports saloon until Prohibition. To this day, no Boston baseball team has won the championship of the world without Nuf Ced being present at all home games.

Jim Naismith invented basketball in 1891.

Chester Drinkwater became one of the richest men in America, gaining his fortune building ball yards and amusement parks outside the city, running streetcar lines to them and selling real estate all along the way. The only locale where this scheme did not work was Mudville, where, at considerable loss, Drinkwater let many land options lapse. Returning on the Titanic from his honeymoon with his fourth wife, the Countess Nina von Munschauer, 23, Drinkwater went to a watery grave.

Grumpy old Cyrus Weatherly, the town miser, refurbished Mudville Grounds after the exciting '88 season, and for decades it was known as the Jewel of the Bushes. Taking this cue, Alfred L. Evans Jr. urged his bank to support the redevelopment of the entire East Side, and the area became a national model for downtown revival. Only after World War I, when the East Side population had become largely Italian, Lithuanian and Pole, were the old Mudville Grounds razed. In 1976 a real estate developer put up middle-class housing for blacks. The area is now known as Covent Gardens Estates, and on the actual site of the diamond where Casey struck out is a 24-hour convenience store.

The Left Arm of God: Sandy Koufax was more than just a perfect pitcher

Timothy F.X. Casey finished the '88 season with Mudville, but though he continued to have a fine year, the events of those days in late May and early June seemed to have extracted some spirit from him that he never regained. He and Flossie became engaged, and on the day after the season ended in September, they eloped.

The Caseys spent the next couple of years traveling in America, investing their fortune in prime real estate, buying downtown tracts in such promising minor league towns as Dallas, Seattle and Los Angeles. However, Caseyhad never stopped thinking about what Mr. Evans had once said to him in Mudville. So when Flossie became pregnant, he went back to school, enrolling, in the autumn of 1891, in the very first freshman class at a small new institution that was known as Leland Stanford Jr. University. He graduated with high honors in 1895.

The Caseys settled in Stockton, Calif., where he quickly made his mark in trolleys. Flossie bore him four daughters, and Casey became a pillar of the community -- daily communicant, councilman and, finally, philanthropist.

Thayer's poem became more and more famous, spawning vaudeville skits, books, paintings, songs, movies, even a whole opera. The supposedly fictional Caseybecame something of an American Dauphin, because for years all sorts of washed-up ballplayers maintained that they had been the model for the Mighty One. But after that famous day in Mudville, the real Casey only told one person who he actually was.

That was his nephew George, son of Casey's lefthanded twin sister, Kate. Once in 1909, when he had to travel East on trolley business, Caseyvisited Kate in Baltimore, and the young lad seemed so keen on baseball that Casey took him over to a corner table in the family saloon on Conway Street and told him the tale of '88. ''But Uncle Timothy, why did Mr. Thayer end his poem the way he did?'' young George asked.

''Aw, you know sportswriters. They only write what makes a good story,'' Casey said.

Young George especially liked the part about Casey pointing to centerfield, daring to foretell a home run. ''Imagine a player doin' a thing like that,'' George said.

Over the years Casey played a lot of golf. He was long off the tee but dicey around the greens. He and Flossie traveled a lot -- to Europe, to Lake Louise and to the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. They had an even dozen grandchildren, but, of course, the name Casey had run out.

Then, in the spring of 1941, Casey's health began to fail, and he took to ! his bed in June. He knew by then that the jig was up. He got weaker and weaker. It was the 75th summer of his life.

Three of his daughters still lived around Stockton, but Mary Louise had moved to San Francisco, so Flossie called her on July 17 and said she had better come. She brought her youngest son, Casey's favorite grandchild, John Lawrence Sullivan Gambardella. They just made it to Stockton, to the old family house, in time and went directly to the master bedroom, where the old man lay.

''Well, Johnny, how's tricks?'' Casey said, just barely getting the words out. He was going fast. Peacefully, but fast, the sands of his time, 1867-1941.

''Oh, I'm O.K., Grandpop,'' the boy said, ''but I heard on the radio the Indians got DiMaggio out tonight. So it ends at 56 in a row.''

Casey shook his head a bit, and he said, ''Well, if he's any good, he'll get over it.''

''Yes, sir.''

Mary Louise kissed her father, and then she stepped back next to her sisters so her mother could stand closest to the old man. Flossie leaned down and kissed Casey gently on the forehead and squeezed his hand. He sighed, and his eyes began to close. He could all but see the angels now. But then, somehow, Casey forced one more breath of life into his body, and he opened his eyes, even smiled a tiny little bit. Looking up at his beloved Flossie, he said, ''Oh, somewhere in this favored land, the sun is shining bright.''

Then Casey closed off his smile, turned down his eyes and died. Flossie kept hold of his hand and said, ''The band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light.''

The four daughters turned to look at one another, tears in their eyes, but wondering what in the world had come over their mother. ''And somewhere men are laughing,'' Flossie went on. ''And somewhere children shout.'' She smiled broadly and didn't say another word.

As for the one other principal in this story, as for baseball, it grew to become the national pastime and lived happily ever after.

Frank Deford is among the most versatile of American writers. His work has appeared in virtually every medium, including print, where he has written eloquently for Sports Illustrated since 1962. Deford is currently the magazine's Senior Contributing Writer and contributes a weekly column to SI.com. Deford can be heard as a commentator each week on Morning Edition. On television he is a regular correspondent on the HBO show Real Sports With Bryant Gumbel. He is the author of 15 books, and his latest,The Enitled, a novel about celebrity, sex and baseball, was published in 2007 to exceptional reviews. He and Red Smith are the only writers with multiple features in The Best American Sports Writing of the Century. Editor David Halberstam selected Deford's 1981 Sports Illustrated profile on Bobby Knight (The Rabbit Hunter) and his 1985 SI profile of boxer Billy Conn (The Boxer and the Blonde) for that prestigious anthology. For Deford the comparison is meaningful. "Red Smith was the finest columnist, and I mean not just sports columnist," Deford told Powell's Books in 2007. "I've always said that Red is like Vermeer, with those tiny, priceless pieces. Five hundred words, perfectly chosen, crafted. Best literary columnist, in any newspaper, that I've ever seen." Deford was elected to the National Association of Sportscasters and Sportswriters Hall of Fame. Six times at Sports Illustrated Deford was voted by his peers as U.S. Sportswriter of The Year. The American Journalism Review has likewise cited him as the nation's finest sportswriter, and twice he was voted Magazine Writer of The Year by the Washington Journalism Review. Deford has also been presented with the National Magazine Award for profiles; a Christopher Award; and journalism honor awards from the University of Missouri and Northeastern University; and he has received many honorary degrees. The Sporting News has described Deford as "the most influential sports voice among members of the print media," and the magazine GQ has called him, simply, "The world's greatest sportswriter." In broadcast, Deford has won a Cable Ace award, an Emmy and a George Foster Peabody Award for his television work. In 2005 ESPN presented a television biography of Deford's life and work, You Write Better Than You Play. Deford has spoken at well over a hundred colleges, as well as at forums, conventions and on cruise ships around the world. He served as the editor-in-chief of The National Sports Daily in its brief but celebrated existence. Deford also wrote Sports Illustrated's first Point After column, in 1986. Two of Deford's books, the novel, Everybody's All-American, and Alex: The Life Of A Child, his memoir about his daughter who died of cystic fibrosis, have been made into movies. Two of his original screenplays have also been filmed. For 16 years Deford served as national chairman of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and he remains chairman emeritus. He resides in Westport, CT, with his wife, Carol. They have two grown children – a son, Christian, and a daughter, Scarlet. A native of Baltimore, Deford is a graduate of Princeton University, where he has taught American Studies.