Could Jeff Luhnow, AJ Hinch Sue MLB or Astros?

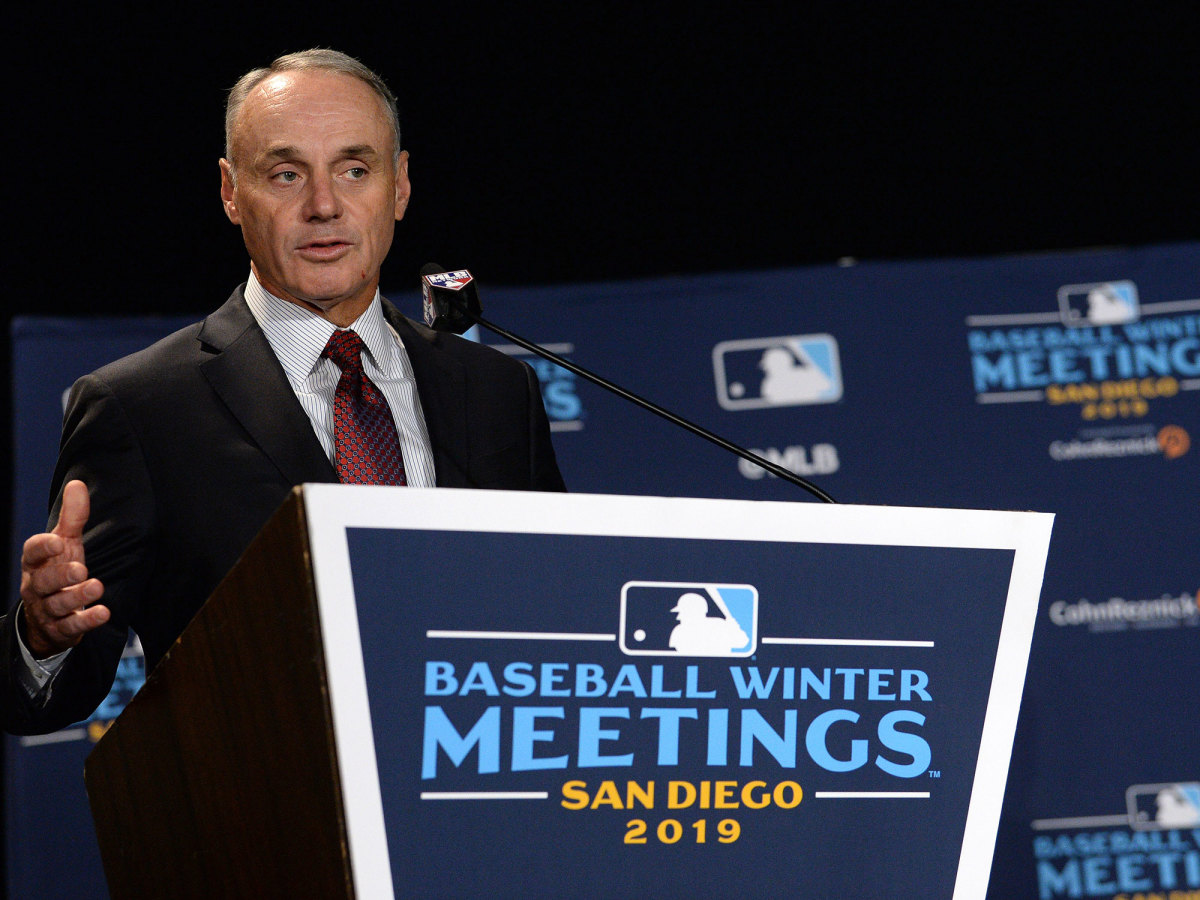

MLB commissioner Rob Manfred on Monday suspended Astros general manager Jeff Luhnow and manager AJ Hinch without pay through the 2020 World Series.

Within minutes of the announcement, Astros owner Jim Crane fired both men from their jobs.

Luhnow and Hinch were found responsible for a conspiracy hatched by Astros players and staff to electronically steal signs. The operation unfolded during parts of the 2017 and 2018 seasons, including during the 2017 postseason when the Astros won the World Series. There were several basic components of the plot. It involved the surreptitious placement of a camera in the centerfield area of the club’s home ballpark, Minute Maid Park, to record opposing teams’ catchers signaling signs to pitchers on the mound. Images were then transmitted to the Astros’ replay review room where the catchers’ signs were decoded by players and staff. Once decoded, the signs were relayed to a person near the Astros dugout who then banged loudly on a trash can. The sequence of the banging informed Astros batters as to the type of forthcoming pitches.

While sign stealing through the human eye has a long and sometimes revered tradition in baseball, the use of electronic equipment to steal signs is viewed as cheating and as undermining the integrity of the sport.

MLB has also punished the Astros organization by voiding four top draft picks—the team’s first- and second-round picks in the 2020 and 2021 MLB Drafts. The team was also fined $5 million, the maximum allowable fine under the MLB Constitution.

In addition, Boston Red Sox manager Alex Cora, who served as bench coach for the Astros in 2017, is expected to face a long suspension for his role in the conspiracy. Manfred’s statement depicts Cora in a very damning light. Cora is portrayed as one of the chief architects of the Astros conspiracy. Indeed, as told by Manfred, Cora “was involved in developing” the sign stealing’s main components and also “implicitly condoned” involvement by Astros players.

Cora is under investigation as part of an ongoing MLB investigation into sign stealing by the Red Sox during the 2018 season—a season in which the Red Sox won the World Series. Given Cora’s alleged involvement in two sign-stealing conspiracies, Cora could ultimately face the longest suspension of persons implicated in electronic sign stealing. Cora’s suspension could last for several seasons. It’s not out of the question that Cora could face a lifetime ban with periodic opportunities to apply for readmission.

Separately, Manfred suspended former Astros assistant GM Brandon Taubman for one year. In October, Taubman made insensitive remarks in the clubhouse.

Manfred’s authority over MLB executives and managers is final and unappealable

Although Luhnow and Hinch worked for the Astros, not MLB, and although neither man is part of a labor union that negotiates a collective bargaining agreement with MLB, Manfred has sweeping legal authority to exclude both from baseball.

This authority is found in the league constitution, a legal document governing the relationship between MLB and MLB clubs. Under Article II of the constitution, Manfred has the power to investigate “any act, transaction or practice charged, alleged or suspected to be not in the best interests of the national game of Baseball” and to determine “what preventive, remedial or punitive action is appropriate in the premises, and to take such action either against Major League Clubs or individuals, as the case may be.”

Manfred is thus judge, jury and executioner. He’s also, as noted below, essentially the appellate court and the Supreme Court.

Unlike the CBA between players and owners, the constitution does not establish a formal appeals process for managers and executives to contest a suspension issued by the commissioner. Instead, any disputes must be submitted to the commissioner who, while acting as an arbitrator, “shall have the sole and exclusive right to decide such disputes and controversies and whose decision shall be final and unappealable.”

The constitution also stresses that clubs and executives “agree to be finally and unappealably bound by actions of the Commissioner and all other actions, decisions or interpretations taken or reached pursuant to the provisions of this Constitution and severally waive such right of recourse to the courts as would otherwise have existed in their favor.” In other words, by virtue of their employment with an MLB club, managers and executives accept the rulings of Manfred and agree to not sue over those rulings.

Luhnow might question why he received such a steep punishment. Manfred’s statement acknowledged that the investigation “revealed no evidence to suggest that Luhnow was aware of the banging scheme” and that “Luhnow neither devised nor actively directed the efforts of the replay review room staff to decode signs in 2017 or 2018.” Manfred nonetheless felt that Luhnow, as GM, was accountable, since it was his job to know what players and staff were doing. A neutral arbitrator might find that level of punishment to be unjustifiably severe, but the appointment of such a neutral arbitrator is not contemplated under the constitution.

Luhnow, Hinch and Cora could sue MLB for defamation, but probably won’t

While Luhnow and Hinch are barred from suing over their suspensions (and Cora over his presumed suspension), they and their attorneys could identify another possible avenue for litigation: Manfred’s statements about them could be defamatory.

Keep in mind, internal investigations are limited in a variety of ways. The methods and conclusions from internal investigations are hardly immune from scrutiny.

Manfred’s statement references that MLB’s Department of Investigations interviewed 68 witnesses, 23 of whom played at some point for the Astros. Manfred goes on to stress that the Astros and Crane cooperated and that investigators uncovered a wide scope of evidence. Analyzed evidence included “tens of thousands of emails, Slack communications, text messages, video clips, and photographs.”

While it’s clear that MLB’s investigation into the Astros was comprehensive, if not sweeping, note the following caveats:

• MLB is a private entity and thus lacks subpoena powers. While MLB obtained many documents and while it says the Astros were cooperative, MLB could not legally compel a variety of sources to share emails, texts and other information. Those sources include former employees or former independent contractors of the Astros, journalists who are familiar with the cheating plot and any technology experts who aided the Astros. Perhaps those sources voluntarily shared information. But the larger point is that MLB’s investigation was not necessarily complete. Also, while 68 witnesses is a large number, it’s not necessarily the full roster of “people in the know.”

• Manfred’s statement acknowledges that the investigation did not shed sufficient light on which players were most to blame. This acknowledgment, Luhnow, Hinch and Cora might stress, is important since it highlights limitations to the investigation’s conclusions. If Manfred wasn’t sure about the players, why was he so sure about the GM, manager and bench coach?

• Witnesses in a private investigation are not under oath, meaning they can lie or omit knowledge without the threat of a perjury charge. Many of the 68 witnesses who spoke with MLB had contractual reasons to be truthful, but they faced no risk of committing a crime by knowingly lying, exaggerating or neglecting to mention certain things. Like all people, witnesses in an investigation may have professional and personal reasons to downplay their culpability and direct it towards others. Did that happen here? We don’t know, but the more important point is that the design of the investigation makes it possible for lying, exaggerating or omitting to occur.

• Manfred’s statement includes a litany of specific, factual statements. If any of those statements are incorrect, they would empower a potential defamation case.

To that end, if Luhnow, Hinch and Cora believe they have been wrongfully railroaded, and if they can identify untruthful statements by Manfred or by any witnesses whom MLB relied upon, they could bring lawsuits for defamation. They could argue that untrue and reputationally damaging statements have been made about them.

Leagues are hardly perfect with investigations. For instance, the NFL’s respective investigations into the New Orleans Saints and New England Patriots for “Bountygate” and “Deflategate” were riddled with problems that led to unproven (some would say untrue) assertions. MLB’s investigative approaches have also attracted criticism. In the Pete Rose betting investigation, then-MLB commissioner Bart Giamatti effectively admitted to reaching adverse conclusions about Rose before the league had reached a decision.

Defamation lawsuits by Luhnow, Hinch and/or Cora would face hurdles. For one, each of the three men is a public figure, meaning each would need to establish “actual malice.” This threshold would require a finding that MLB expressed false and defaming information about them or had reckless disregard for the information’s truth or falsity. Actual malice would be difficult to prove so long as MLB conducted a thorough and even-handed investigatory process. MLB would also highlight that statements expressed as part of a legal proceeding are typically exempt from defamation claims. This exemption arguably includes statements made in an internal investigation that poses legal consequences.

Luhnow, Hinch and Cora also have professional reasons to not sue. Each presumably hopes to resume their MLB careers once their suspensions end. If they sue, they could become “radioactive” for MLB clubs, who would be hesitant to hire them if they are waging litigation against MLB.

Astros and Red Sox could fire suspended employees “for cause”—and set off litigation

As noted above, the Astros have already fired Luhnow and Hinch. It’s possible, if not likely, that Red Sox owner John Henry will reach the same determination with Cora. The classification of the firings could pose legal consequences.

The employment contracts for Luhnow, Hinch and Cora are not publicly available, but they almost certainly contain language that contemplates when their employer could fire them “for cause” or “with cause.” Such a designation would authorize the team to terminate employment on account of misconduct, unethical activity or illegal behavior. Usually a “for cause” firing relinquishes or reduces the obligation on the part of the employer to pay out the remainder of the contract.

There would be risks on the part of the Astros and Red Sox in firing Luhnow, Hinch and Cora with cause. Each would have incentive—perhaps millions of dollars of incentive—to sue their employer for breach of contract. Each would argue his contract’s language didn’t authorize a for cause firing. In a lawsuit, each could also use the pretrial litigation process to raise questions about remaining employees with those clubs. Pretrial litigation would involve the taking sworn statements and the compelled sharing of emails and other sensitive information.

If instead the firings are classified “without cause”, we won’t see breach of contract lawsuits. A “without cause” firing is one where an employer decides to let a contract employee go, not for any unethical misconduct but because the employer would like someone else in the job. For instance, when a team fires a manager of a losing team, the firing is without cause. A without cause normally means greater compensation for the fired employee. Particularly given that both Crane and Henry are billionaires, odds are they will simply pay out the fired executives contracts rather than risk a legal fight over what to them may be relatively small change.

By not suspending players, MLB averts a potential labor battle with the MLBPA

Manfred’s report pins much of the blame for the sign stealing on New York Mets manager Carlos Beltrán, who played for the Astros in 2017. Mandred says Beltrán and other players “discussed that the team could improve on decoding opposing teams’ signs and communicating the signs to the batter.” This discussion, Manfred claims, prompted Cora to “arrange for a video room technician to install a monitor displaying the center field camera feed immediately outside of the Astros’ dugout.” Manfred leaves no doubt in assigning blame onto players when stating, “[T]he 2017 scheme in which players banged on a trash can was, with the exception of Cora, player-driven and player-executed.”

The report suggests, then, that players should be punished. Manfred disagrees. He writes that it would be “difficult and impractical” to determine which players ought to be held accountable or their “relative degree of culpability.” He also stresses that many of the players now play for other clubs (though he didn’t emphasize that same point with respect to Cora moving from the Astros to the Red Sox).

Manfred’s decision to exclude players from punishments is likely a wise one. He knew that to punish players based on an incomplete record would probably trigger appeals by those players. Unlike Luhnow, Hinch and Cora, MLB players are protected by a CBA, which contemplates a grievance process for player suspensions (albeit one where Manfred or a delegate of his choosing is again the final arbitrator).

Manfred is likely also mindful of timing. A fight with MLBPA wouldn’t occur in a vacuum. The current CBA between MLB and MLBPA will expire on Dec. 1, 2021 at 11:59 pm ET. A new CBA will be the subject of labor negotiations over the next year. An ongoing battle with the MLBPA over the Astros’ sign stealing would be an unhelpful side issue for MLB during this time.

Fans could sue Astros and MLB, but litigation likely wouldn’t go far

Manfred’s report indicates that the Astros gained an unfair advantage in 2017. This advantage presumably helped them defeat opposing teams. Fans of those opposing teams, particularly if they travelled to Houston to watch a game in Minute Maid Park, could argue that they were cheated. In theory, they could sue the Astros and MLB, arguing that they were victims of negligence or fraud. To that end, the fans could insist that games marketed by MLB to consumers as competitive events were, unbeknownst to fans, fixed and shams.

There are a number of reasons why such litigation would likely fail. First, some of the potential claims are likely time barred. Texas features a two-year statute of limitations for negligence and other personal injury claims, while it features a four-year statute of limitations for fraud and breach of contract.

Even if statute of limitations weren’t an issue, courts have routinely rejected theories of unlawful conduct offered by frustrated fans.

Fans who attend MLB games are owed very limited protections from their tickets. They are entitled to watch a game between two specific teams from a particular seat in the ballpark. They are also entitled to a safe environment from which to watch a game (though even “safe” is a bit of an overstatement since they are not owed protection from foul balls or flying equipment). In other words, fans who attended Astros games likely got what they paid for, even if the Astros were breaking rules.

Also, disappointment in one’s favorite team losing is a not a “legal harm.” It’s a sports harm and one that we all live with as fans.

Michael McCann is SI’s Legal Analyst. He is also an attorney and the Director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute at the University of New Hampshire Franklin Pierce School of Law.