The Meaning Behind MLB's Unprecedented Astros Punishment

The Official Professional Baseball Rules Book—a totally distinct entity, somehow, from the Official Baseball Rules—is not much concerned with mechanisms of enforcement. It rolls the rules out one after another; there is almost no effort to break down the “or else” that lurks behind each one. There are a few allusions to “penalties,” but their details are never sketched in, and the reader is left to fill in the blanks. There is no sense of what it means to break the law.

And then there is one rule, thrown in the middle of the book, after “Obligations of Participants” and before “Classification of Minor Leagues,” that is just a giant “or else,” weighty enough to warp all of the entries around it. This is Rule 50(a), on page 157: “Enforcement of Major League Rules,” which exists to ensure that the commissioner can enforce all of these rules however the hell he wants. (Er, with “action consistent with the commissioner’s powers under the Major League Constitution,” which, given the history of those powers and their summary in the Constitution, is a more polite read on “however the hell he wants.”)

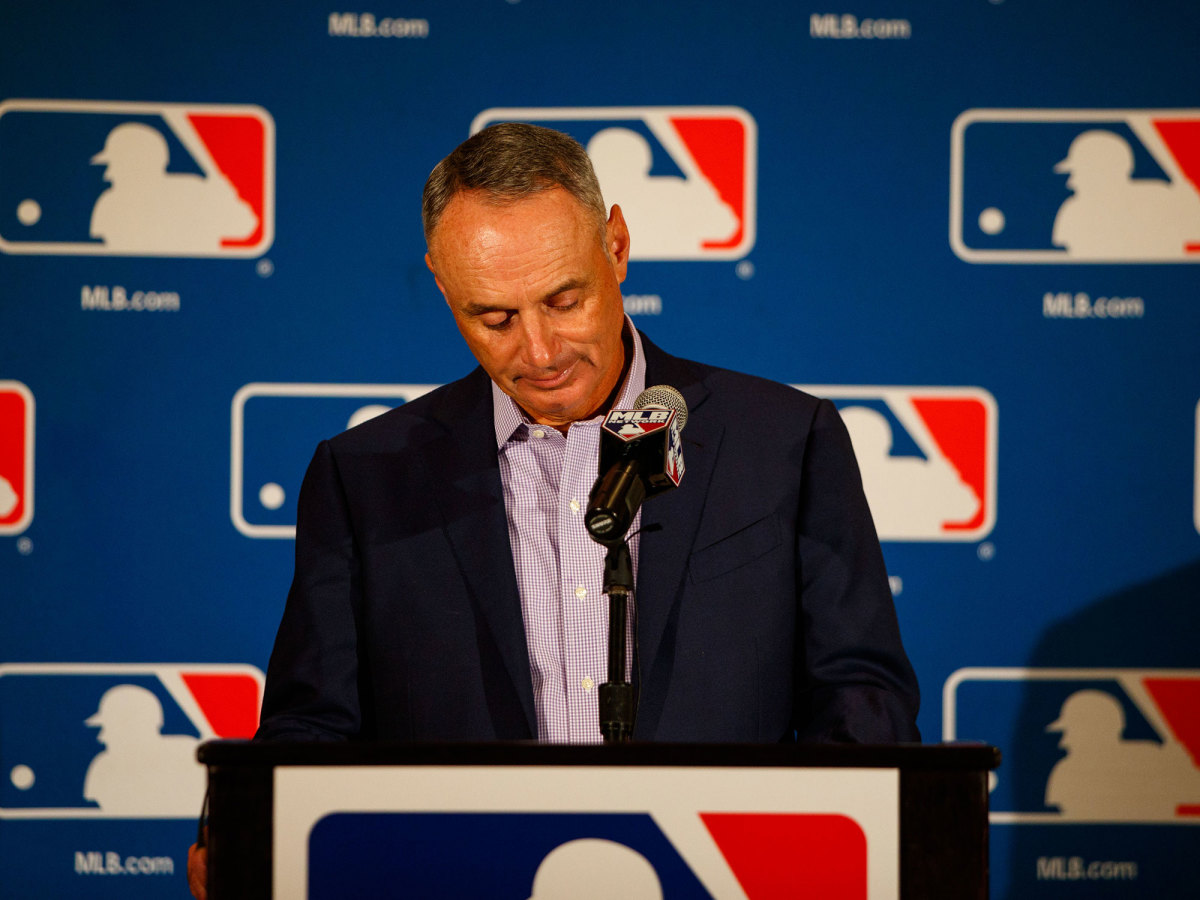

Commissioner Rob Manfred’s verdict on the Astros’ sign-stealing scandal showed this aptly. Handed down on Monday, he included yearlong suspensions without pay for general manager Jeff Luhnow and manager A.J. Hinch; the loss of the team’s first- and second-round draft picks for both 2020 and 2021; a $5 million fine, the maximum allowed under the MLB Constitution; and a spot on the league’s ineligible list for former assistant general manager Brandon Taubman. A public conversation spun out on whether all of this was too harsh or not harsh at all. It spun harder, suddenly lopsided, with the news that the Astros had moved forward by firing Luhnow and Hinch.

But the question of harshness is hard to answer without another foundational question: What did MLB want to do here? If that sounds self-evident—"punish the Astros”—it is and it isn’t, if only because there are different kinds of punishment, different theories of its purpose, even different ways to define the Astros. (The players, for instance, could be in some of those definitions; Manfred explicitly cut them out.) Any measurement of harshness here is a vector rather than a line; direction is crucial. “Punish the Astros” where, to what end?

There are punishments meant to inflict pain and some meant to serve as deterrents and some meant to bring about justice. There are some meant to work in the name of public relations. There are some that try to do several of these at once. And MLB’s rulebook does not have much of a coherent internal framework to delineate them—MLB has Rule 50(a), all loose boundaries and blank lines. Baseball has Rob Manfred, but it does not have a grand unified theory of punishment. So what did MLB want to do with its punishment of the Astros?

Punishment as a Penalty

This is punishment that is meant to hurt. It is incisive; it does not bother to look outside at others. It is the first- and second-round draft picks for 2020 and 2021.

The rest of the punishment package might have very little influence on the actual future of the team: Houston could have (easily) won in 2020 without Hinch and Luhnow. Really, they’ve won in the past in part because they’ve built out the staffs around these two men so deep and so like them. The dismissals may be painful, but only personally so, not institutionally. The team does not hurt here. And the fine? The fine is $5 million. But draft picks—draft picks make a difference. They’re the most valuable sort of lottery ticket; they’re impossible to work around or pick up elsewhere or assess in full. They make it harder to win. They hurt.

Punishment as a Deterrent

This is punishment that is meant to make a statement, that looks outward, that asks: Would you want this to be you? These are the one-year suspensions (and the Astros' subsequent decision to fire Hinch and Luhnow). They draw a line around the action and connect it to a result: This is not about the organization. This is about you, who will receive a punishment that has a place in the record books, who will have an invitation to lose your job, who will be held responsible for all to see. There is nowhere to hide.

Luhnow tried to push against this in his statement on the matter. “I am not a cheater,” he wrote. “Anybody who has worked closely with me during my 32-year career inside and outside baseball can attest to my integrity. I did not know rules were being broken.” But the point of the punishment was not to label him a cheater or press him on his integrity or determine anything about the rules. The point of the punishment was to hold him responsible for others to see. The point of the punishment was that he would not be able to hide. And in the future, no one else in this situation will be able to either.

Punishment as Justice

This is tricky. This is punishment meant to restore what was knocked askew.

In theory, this would find every illegally obtained advantage, add them up, take them away from the Astros. But that process does not and cannot exist. The precise advantage is unknowable. The games cannot be replayed. (And, even if they could, they may not end any differently.) The World Series parade’s confetti cannot be recollected. There is no natural path forward here.

The title could be vacated, of course. All of the 2017 wins could be vacated. But that does not balance the scales so much as it asks everyone to simply ignore that they had previously had a thumb of unknowable influence on them. It is not justice. None of this is.

Punishment as Optics

Then there is punishment that does not fit with any of the above—that is drawn out primarily with consideration for how it looks. There is, for instance, the $5 million fine.

There are some contexts in which that sum will matter to a baseball team—any club will go to arbitration over less—but when the context is a question of economics, and not a question of principle, it cannot ever matter too much. On the scale of a baseball team? There’s just too much here to see an obstacle in $5 million. It’s easy to rationalize. That’s the cost of doing business. That’s one sour decision on a contract. It does not hurt anyone; it does not mean anything; it does not make someone stop and think twice. All of the other numbers here are just too big. What’s $5 million? One year of a mediocre player on the market. The gate receipts for a few games. Is this worth more than that?

Of course, $5 million is also the maximum that a team can be fined under the Major League Constitution. It would be nothing, if it were not constitutionally everything.

And then there is the last clause of the Astros’ punishment: Brandon Taubman’s place on the ineligible list. This is not a natural fit; Manfred notes in his report that the discipline here is not tied to the sign stealing. But he puts it in the conversation, anyway, and asks readers to connect the two. Taubman’s targeted outburst toward female reporters prompted a previous investigation of its own from MLB, and Manfred draws a direct line from that one to this:

“But while no one can dispute that Luhnow’s baseball operations department is an industry leader in its analytics, it is very clear to me that the culture of the baseball operations department, manifesting itself in the way its employees are treated, its relations with other Clubs, and its relations with the media and external stakeholders, has been very problematic. At least in my view, the baseball operations department’s insular culture—one that valued and rewarded results over other considerations, combined with a staff of individuals who often lacked direction of sufficient oversight, led, at least in part, to the Brandon Taubman incident, the Club’s admittedly inappropriate and inaccurate response to that incident, and finally, to an environment that allowed the conduct described in this report to have occurred.”

Of course, Taubman’s outburst is meaningfully different from unlawful sign stealing. But the two exist in the same world. They grow out of a refusal to believe that the rules apply.