'Clean It Up. It Must Stop': MLB Is in an Ethical Crisis

Imagine if the Mets and Carlos Beltrán tried to ride out his part in the Houston Astros’ sign-stealing scandal.

His tenure as manager of the team would begin with a news conference in which he not only would have to account for being a mastermind in the team’s systematic cheating, but also have to answer detailed questions about his misuse of technology, such as why he didn’t stop when warned, what he did in the 2017 World Series and when his unethical espionage began. (In the first three seasons with replay monitors near the dugout, 2014-16, Beltrán played for the New York Yankees. He was traded to Texas for the final two months of 2016 and signed with Houston for 2017).

He also would have to explain why, when the scandal first broke, he lied multiple times to reporters in denying he misused technology to decode signs.

And then he would have to explain why, having cheated the system even after the warning from the commissioner’s office, as a manager he should be one of the key people the office trusts to ensure compliance of those very regulations he flaunted.

That’s how someone who never managed before would begin his first managerial job: as an exposed cheater, liar and untrustworthy steward of the game.

No, it all was too big, too corrosive and too enduring a burden to just put in a box, close the lid and leave it behind.

When you play out that scenario, you understand why Beltrán and the Mets had to “part ways,” as the euphemism goes these days for someone so toxic he must be fired.

But there is something much bigger going on here. It’s bigger than Beltrán and bigger even than the Astros’ scandal. Baseball is smack in the middle of a crisis of ethics. “Finding an edge” has become the mantra of an increasingly data-driven game and world. And as it does, it has spawned one scandal after another in the sport.

Is it too much to ask to find a general manager and manager who actually plays by a fair code of conduct?

If there is anything good to come out of the Astros’ sign-stealing scandal it is that people in baseball are hit with an attack of conscience. The sport needs an awakening. If the jobs of AJ Hinch, Alex Cora, Jeff Luhnow and Beltrán are part of the cost, so be it.

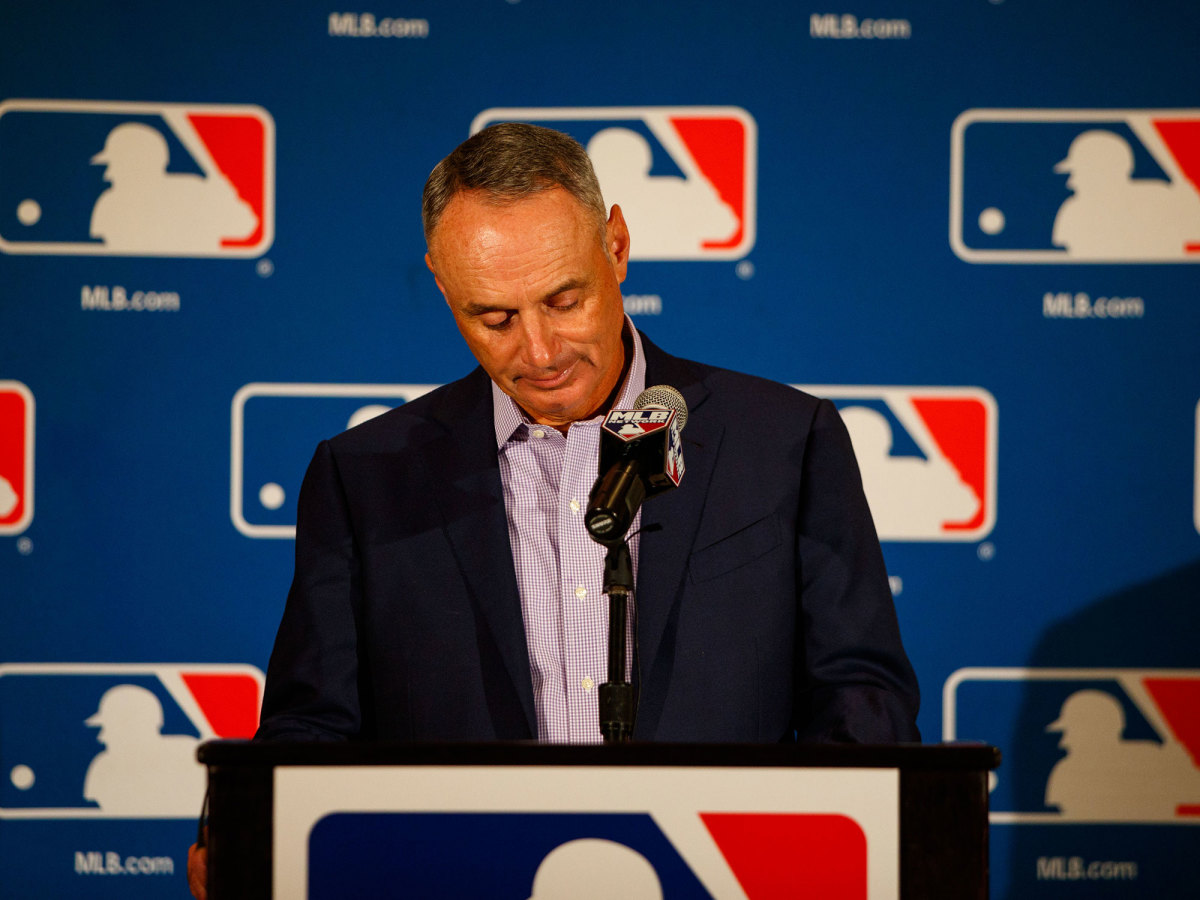

Last November, as the Houston scandal broke, commissioner Rob Manfred hired a speaker to address general managers at their annual meeting about the need to humanize the game more. As the power of influence in the game shifted from the dugout to the front office–and specifically, a generation of whip-smart efficiency and actuarial experts who mined new levels of understanding of this game of percentages–the language of the game shifted. Luhnow worked at McKinsey as a management consultant before he entered baseball with the Cardinals. Oakland president Billy Beane, a former player and one of the high lords of this evidence-based movement, likes to say, “When you get down to it, we are all actuaries”–trying to cast future outcomes on past data.

So players become “assets” or “a two-win player.” Relief pitchers are “fungible.” Executives are “human capital.” Coaches are “high performance” experts. The chance to score a run, win a game or secure a postseason berth are defined as a finite percentage.

Baseball earned a place in so many hearts on its romance. But it has begun to sound like the insurance and banking industries. When Luhnow wanted a “baseball ops” hire in Houston, he posted a listing for someone with expertise in quantitative analysis, which is how he plucked Brandon Taubman from investing banking, where he valued derivatives. Taubman rose quickly to his assistant. With both gone, owner Jim Crane is overseeing the baseball operations before he can find somebody who has experience with, you know, actual major league baseball.

Manfred saw the deepening of this trend. The guest speaker told the general managers about being careful how they frame the game to their fans. Baseball is a diversion, or, if you’re old enough to remember, a pastime. People come to it because they want to get away from the weight and density of the business world, not be reminded of it.

Now, the game is a $10 billion business, so this is not a quaint little hobby we’re talking about. But it’s important for the game to accentuate the narrative that it is sport—the antidote from the business world, the rare respite for a family to sit outside and actually watch something together and not be on separate screens. If you keep talking about the players they root for as “assets,” the speaker told them, you will continue to dehumanize a game that needs to be aspirational and accessible.

By the winter meetings a month later, in December, Manfred was hip-deep in the Houston investigation. He first thought he would have the investigation done in a month, but the more threads he pulled the more work had to be done. He was chapped that after he had put teams on notice twice about the misuse of technology to steal signs–Sept. 15, 2017, and March 27, 2018–the Astros kept cheating. Manfred was nearing the five-year anniversary of his first term as commissioner, and he was tired of dealing with unethical behavior. And so at the winter meetings he put major league managers on notice.

“Essentially, he read us the riot act,” said one manager who was there.

Manfred ran down the list of issues that kept coming across his desk just in the past three years:

• In 2016 he suspended Padres GM A.J. Preller 30 days for hiding medical records from trade partners–the equivalent of keeping two sets of books.

• In 2017 he placed former St. Louis scouting director Chris Correa on the permanently ineligible list and fined the Cardinals $2 million for Correa hacking into the database of the Astros. Correa also was sentenced to 46 months in prison.

• In 2017 he banned for life Braves GM John Coppolella for violating rules regarding international signings. Sources said a lack of truthfulness in the investigation influenced the penalty against Coppolella.

• In 2017 he fined the Red Sox for stealing signs off the replay monitor and transmitting them with a smart watch. He also fined the Yankees for improper use of the dugout phone to gain information off the replay monitor.

• In 2018 he received so many complaints about teams stealing signs electronically that in the postseason he stationed MLB security officials near every replay monitor and dugout to try to ensure a fair game–the baseball version of calling in the National Guard to an emergency.

• In 2019 he launched what he called “the most thorough investigation” ever undertaken by the commissioner’s office, the one into highly systematic sign stealing by the Astros in 2017 and 2018. He soon would launch another one into the 2018 Boston Red Sox. And now we have four bright baseball men thrown out of their jobs because of a cheating scandal–for not playing baseball the right way.

Manfred, according to the source in the room, told the managers, “Clean it up. It must stop. It will stop.”

“The reaction was interesting,” the manager said. “I think probably a few guys were thinking, ‘He’s talking about me.’”

In one month we hope to be restored by the pictures from Arizona and Florida of youthful ballplayers under the winter sun lazily tossing baseballs to one another and giving us once again the beautiful sound of bat meeting baseball, which for us is what the chirp of a bird is to an ornithologist. This is why we watch. It’s the simplicity of the game that soothes us. Every game has a binary outcome. Every event is definable. Runs, hits and errors. Wins and losses. Its beauty is in its simplicity.

We don’t want championships that make us do mental gymnastics to decide whether they are inauthentic. We don’t want player analysis to be derivative valuation. We don’t want ethical dilemmas to test our fandom.

We want a clean game decided by fair competition. Clean it up.