Hank Aaron Never Forgot How America Treated Him. We Shouldn't, Either

Years ago, after one of the most illustrious careers in the history of the sport, Hank Aaron donated all his memorabilia to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. His 1957 World Series ring; the bat that struck his 3,000th hit, in ’70; his Presidential Medal of Freedom, awarded by George W. Bush in 2002—they all rest now in Cooperstown, N.Y. Aaron, who died on Friday at 86, kept only one collection for himself: the boxes of racist hate mail he received.

Aaron never forgot how America treated him. America shouldn’t, either.

Aaron was one of the greatest baseball players of all time. He held the home run record, with 755, until Barry Bonds surpassed that mark in 2007, and Aaron still holds the RBI record, with 2,297. He often said that his favorite of his statistics was that in 23 years, he never struck out more than 97 times in a season.

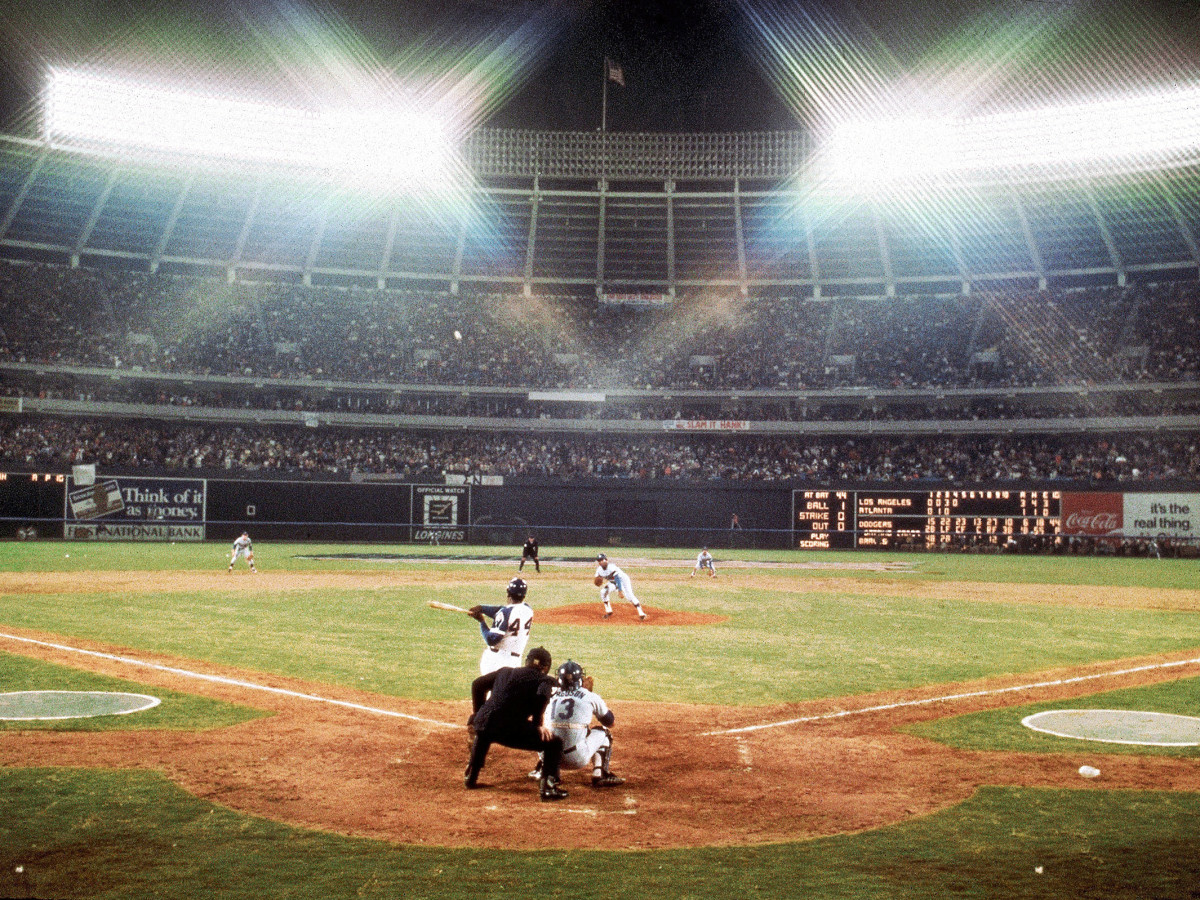

His chase to break Babe Ruth’s home run record captivated the nation. When, in the fourth inning of the Braves’ 1974 home opener, Aaron finally walloped No. 715 into the left-field bullpen, he should have felt joy. He felt only relief. “I just thank God it’s all over,” he told the 53,775 in attendance. Jimmy Carter, then the governor of Georgia, was there that day. Bowie Kuhn, the MLB commissioner, wasn’t.

Vin Scully, on the call for the Dodgers, delivered his famous line: “What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.”

That was all true. Also true was that the Braves had hired an Atlanta police officer, Calvin Wardlaw, to accompany Aaron everywhere he went. They registered Aaron under aliases in hotels: his mother’s maiden name, his assistant’s last name. They considered, then discarded “Babe Ruth.” Eventually they settled on A. Diefendorfer. Security ushered him through the back doors of ballparks to avoid crowds. The scares intensified as he neared the record. Someone threatened to kidnap his daughter Gaile. Several letter-writers identified the specific game during which they planned to shoot Aaron. The team turned the death threats—stacks of letters every day—over to the FBI. He was on edge even with autograph-seekers, whose pens flashed like guns. The Atlanta Journal pre-wrote an obituary, just in case.

The night he broke the record, the Braves tripled security at Fulton County Stadium. Wardlaw kept his hand on his .38-caliber gun. When Aaron reached home plate, his mother, Estella, smothered him with a hug—not from delight, she said later, but to shield him from snipers.

As a child growing up in Mobile, Ala., Aaron recalled at his 80th birthday party, he would wake in the middle of the night at his mother’s urging. “Get under the bed!” she would cry. The Ku Klux Klan was marching through town. When he played for the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League as a teenager, he once said, he and his teammates sat in the dining room of a Washington, D.C., restaurant and listened to the staff break all the dishes they had used. “If dogs had eaten off those plates, they'd have washed them,” he said later. As a minor leaguer, he was barred from staying in the same hotels as his white teammates. Throughout his career, many writers engaged in the racist tropes that he was unintelligent, successful only because of his natural gifts.

In The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron, author Howard Bryant wrote, “Hitting, it could be argued, represented the first meritocracy in [Aaron’s] life.”

Some baseball fans—some Americans—might be tempted to see all of this as the distant past, to view his story as a Disney movie about triumphing over oppression. Aaron never did. He kept that hate mail, he said in 2014, “to remind myself that we are not that far removed from when I was chasing the record. If you think that, you are fooling yourself. A lot of things have happened in this country, but we have so far to go. There's not a whole lot that has changed.

“We can talk about baseball. Talk about politics. Sure, this country has a Black president, but when you look at a Black president, President Obama is left with his foot stuck in the mud from all of the Republicans with the way he's treated.

“We have moved in the right direction, and there have been improvements, but we still have a long ways to go in the country.

"The bigger difference is that back then they had hoods. Now they have neckties and starched shirts.”

Even as he slowed physically, he focused on the battles still to be fought in America. After Minneapolis police killed George Floyd this summer, Aaron said, “I’m not able to move around much anymore. But if I could, I’d be out there marching. I’d be right there at the front of the line.”

Aaron triumphed amid, not over, oppression. When you think of him, think of the triumph. Think of the oppression, too.