Mariners CEO Explains How to Build a Baseball Team in Bad Faith

Editor's note: Mariners CEO Kevin Mather has resigned and the story has been updated to reflect the news.

Fernando Tatis Jr.'s new contract, a gargantuan 14-year, $340-million extension with the Padres reported last week, stood out for both its length and its value. (Though given how young he is, and how talented, neither of those figures should be that surprising.) But the deal’s most notable feature, at least for this moment, is perhaps something else entirely—its simple commitment to operating in good faith.

The last two months have not been especially promising for homegrown stars in baseball. Tampa Bay traded Blake Snell; Cleveland traded Francisco Lindor; Colorado traded Nolan Arenado. (And all these still lay in the shadow of Boston’s decision to trade Mookie Betts in February 2020.) The conditions for these deals varied—each team’s circumstances were different—but the vibe was the same across the board. These trades were difficult, executives said, but they were necessary, and they had the tortured explanations to prove it. This was about financial flexibility. It was about planning for the future. It was about simply trying to work with the player and do what was best for everyone.

These explanations had two things in common: They were not about trying to build a baseball team that could win, and, somewhat related to that, they were not very good explanations.

By comparison, Tatis’s extension does not require an explanation, because it’s self-evidently good for everyone involved. If you did want an explanation, for some reason, it would go something like this: The Padres want to give themselves a good chance of winning for a long time, Tatis is a player who helps them do that, and so they are interested in making sure that they can win together for the foreseeable future. That is not necessarily exceptional (it is not the first extension of its kind) nor is it an assurance that its terms will stick (Arenado, before he was traded, received a similar extension from Colorado). But it stands in stark relief from so much else that baseball has seen this winter. It’s a young star who was brought up to the big leagues when he was ready, not when it was considered most beneficial for the team to start gaming his service-time clock, now signed to fair terms to stick around for years. It’s a deal to win and a deal to make people happy. It’s a nice way to imagine baseball working.

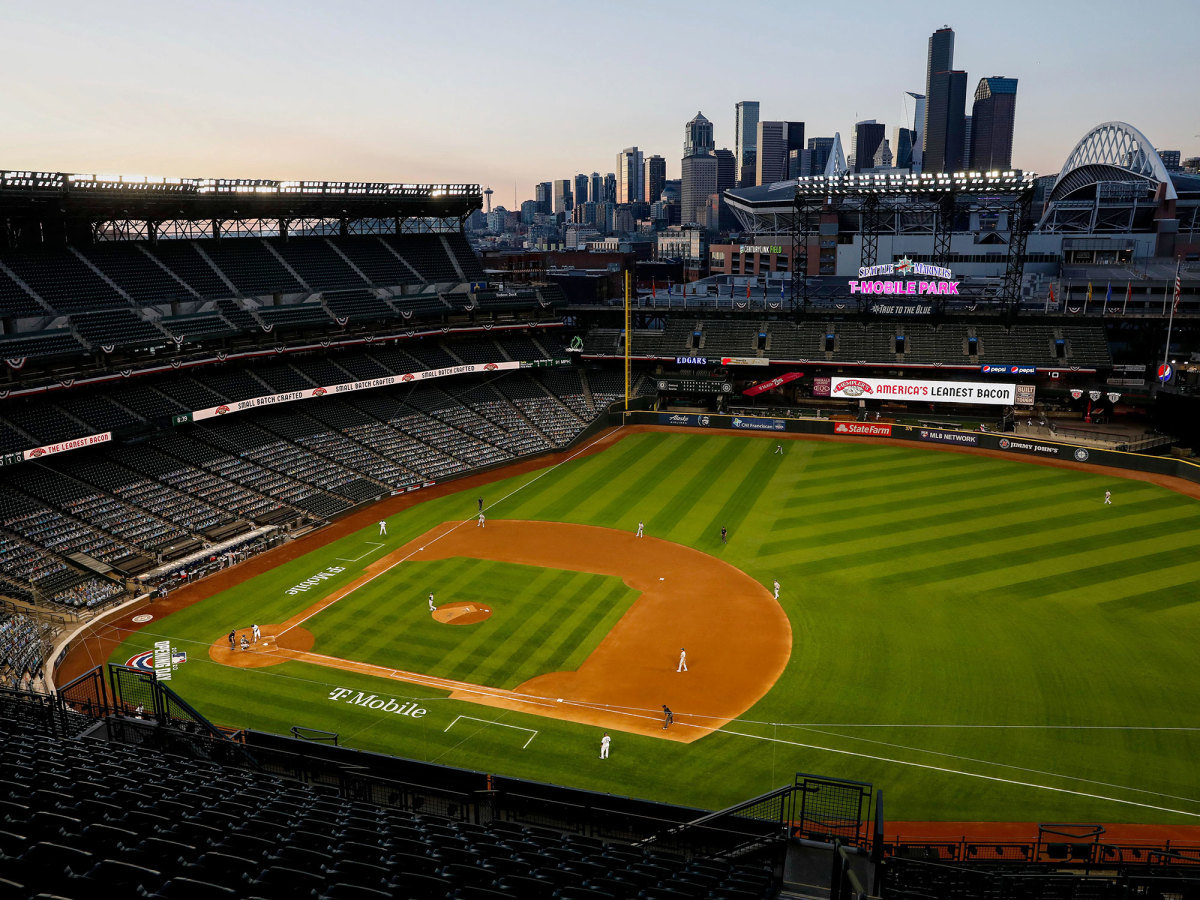

If you liked that nice way to imagine baseball working—if you wanted to head into spring training with this as your most recent model for how baseball executives might approach their jobs—you had all of three days. On Sunday, a video surfaced of Mariners president and minority owner Kevin Mather’s recent conversation with the Bellevue (Wash.) Rotary Club. It was a disaster. He resigned on Monday.

The 46-minute video does not look like it should have been a spot for an executive unraveling—Mather is invited to make a brief opening statement about the state of the team and then fields questions from what appears to be a receptive audience of fans. In other words, it looks like one of the easiest possible scenarios for an executive to navigate, with the bar set somewhere around don’t needlessly offend anyone.

Mather repeatedly stepped on that bar and hit himself in the head with it in some sort of grotesque slapstick routine.

Besides Mariners fans, a quick list of people offended/insulted in Mather's video:

— Ryan Divish (@RyanDivish) February 21, 2021

Kelenic

Julio

Marco

Evan White

Seager

Iwakuma

Japanese players

Latin players

Taijuan

Pax

Luis Torrens

MLBPA

Everrett Memorial Stadium

He dismisses his own players casually, as if he doesn’t realize he’s saying anything that might be considered rude, in response to simple questions. Beloved veteran Kyle Seager is “probably overpaid.” Pitcher Hisashi Iwakuma? “I’m tired of paying his interpreter.” (He goes on to note that the salary of the interpreter is … $75,000.) He wrings his hands about the neighborhood that the team plays in—“we got to do something about the neighborhood”—but notes that he could never give close parking spots to employees who leave the stadium late at night: “I can get away with charging $30, $40, $50 to park in my tiny little parking garage across the street, so I don’t let my employees park there.” He explains why he has waited so long to sign a free agent (“180 free agents still out there on February 5 unsigned, and sooner or later, these players are going to turn their hat over and come with hat in hand, looking for a contract”) and why he has waited to promote top prospect Jarred Kelenic (“We control his major league career for six years, and after six years, he’ll be a free agent. … So probably Triple-A Tacoma for a month”). He offers a strikingly clear vision of what he cares about, and it does not seem to be players, or fans, or a winning team.

Mather has already made an apology and is now gone from the organization. (It takes a special sort of person to turn a Rotary Club gathering into an event where you need to issue a statement with the line, “I am committed to make amends for the things I said that were personally hurtful and I will do whatever it takes to repair the damage I have caused.”) But the damage is done. Mather has shown not just how he thinks about his (now former) job, but how he feels comfortable speaking about it in front of a group, and the latter can still be surprising even if the former is not.

It’s a slap in the face to a talking point that has been pushed after each of the unpopular trades this winter, which goes something like this: A baseball executive does not think like a supervillain. That’s just conspiratorial thinking from unsatisfied fans. An exec is simply trying to do his job under a variety of constraints—he might be making tough decisions, but these are practical financial matters, and he’s not out to get anyone. He understands that players and fans are people. He’s not the sort of guy who is invited to an innocuous setting like the local Rotary Club, gets posed a simple question like “Tell us about Julio Rodríguez” and decides to lead his answer about the highly ranked prospect with, “He is loud. His English is not tremendous.”

Mather tore through that talking point in a matter of minutes. He issued a hurried apology Sunday before resigning Monday, but now the team must still try to explain—explain that he did not mean what he said about service-time manipulation or about holding out on free agents or about players learning to speak a foreign language. Maybe these explanations will be satisfactory. (Though if Sunday night's statement from Mather and Monday's statement from team chairman John Stanton are any indication, they probably won't be.) But it’s worth thinking about the fact that it is possible to operate a baseball team differently, straightforwardly and in good faith, without having to explain at all.