'A Game of Speech'—But Also, For Baseball Interpreters, So Much More

One afternoon in May, the most famous baseball player in the world was running late. Shohei Ohtani had taken the last team bus from the Angels’ hotel in Oakland to the Coliseum, as is his habit on days when he’s slated to pitch. Ohtani’s multitiered gig—as one of MLB’s most powerful hitters and flummoxing pitchers and, increasingly, the sport’s global avatar—requires an intricate itinerary. He throws side sessions before rounds of batting practice. He watches tape of that night’s opposing starter and then studies scouting reports for his own start days later. He finds himself, on occasion, on a bus alongside the Angels’ traveling secretary, his catcher, Kurt Suzuki, and Ippei Mizuhara, a 36-year-old who has never played an inning of organized baseball. On this day, that bus got stuck in a snarl of Bay Area traffic, and the group had to take the train.

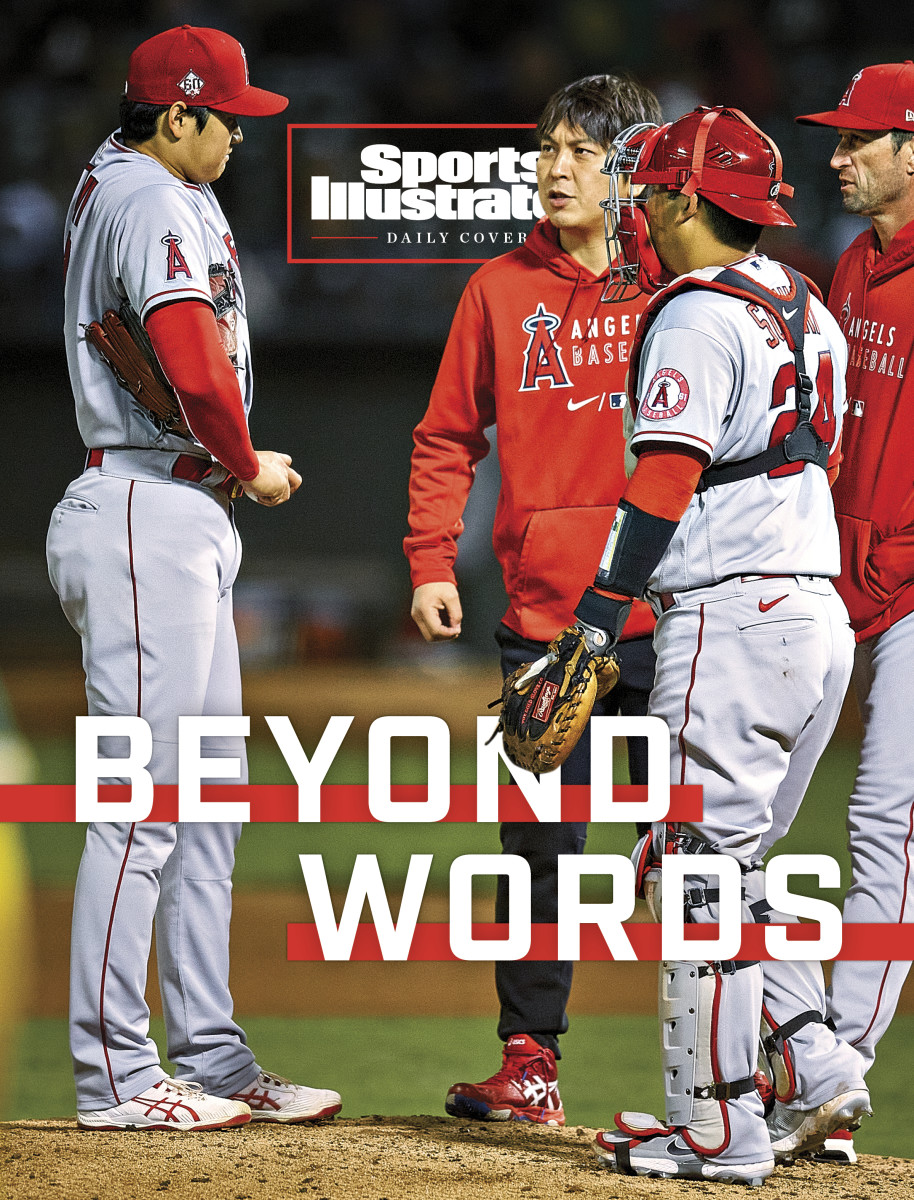

Mizuhara is Ohtani’s personal interpreter. He has held the position since Ohtani came to Anaheim from Japan in 2018, translating for press conferences and locker-side scrums, shorthanding lines of clubhouse banter, and facilitating the fine-grain coaching sessions that help let Ohtani shape his scythe of a swing and lock in his four-seamer. That afternoon, when they reached the BART station, Mizuhara’s phone buzzed with a text from manager Joe Maddon. Should they push Ohtani’s start back a day to give him time to go through a proper warmup? Or would that mess with other elements of the routine? Mizuhara conferred with Ohtani, the two quickly weighing team and individual needs, and sent back the verdict: “Shohei’s good with that.”

At its essence, Mizuhara’s job is to make sure Ohtani understands, and is understood. But the role spills beyond the banks of that description. Ohtani’s agenda—preparation, play, recovery, media availability—becomes Mizuhara’s own, with the interpreter stepping into any number of sub-duties. He speaks Japanese and English and breaks down advanced analytics and recovery timetables. “His schedule’s so unique, there are times when nobody’s around to throw with him,” Mizuhara says. “I’ll step in and play catch.”

Major League Baseball is as rich in international talent as at any point in its history. More than 28% of active players hail from outside the U.S. borders, and many of them prefer to communicate in languages other than English: Spanish, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Mandarin and mashups of baseball-speak that exist somewhere in between. That figure includes superstars set to garner no small number of MVP votes (the Juniors Ronald Acuña and Vladimir Guerrero), Cy Young votes (Hyun Jin Ryu) or both (Ohtani).

The people who make this possible share few distinguishing characteristics but bilingualism and a love for the sport. They are washed-out ex-athletes or onetime megafans who made their way into pro clubhouses doggedly or accidentally. They work across rosters—as Spanish interpreters have since MLB started requiring them in 2016, at the behest of a coalition of players tired of the once-customary practice of asking this or that coach or teammate to translate part-time—or one-on-one, as is usually the case with the smaller number of players from Asian countries. The role is not particularly sought after; there is no horde of econ-degree Ivy Leaguers chasing it, as with almost every other front-office posting. But interpreters know two things better than anyone else. First, that as much as baseball is a game of skill or strength, it is a game of speech. And second, that the work of finding the right word doesn’t stop when the talking does.

In 1964, the Nankai Hawks of the Japanese Pacific League sent three players to participate in the Giants’ spring training as part of a postwar “exchange program.” During the regular season, San Francisco assigned one of these players, a pitcher named Masanori Murakami, to its Class A affiliate in Fresno, home to a sizable Japanese American community whose members provided him lodging and helped teach him English phrases. Infielder Tatsuhiko Tanaka and catcher Hiroshi Takahashi headed to Twin Falls, Idaho, for rookie ball, with no such support system. While Murakami pitched well enough to turn heads in the Giants’ front office, the others faltered, with Takahashi in particular developing a reputation for defensive miscues. He called for more offspeed pitches than his U.S. counterparts, a trademark of Japanese baseball, and struggled to grasp in-game adjustments.

In September of that year, Murakami became the first Japanese player to appear in the majors, while Takahashi completed the program and returned home. “The frustration [with the language barrier] manifested in his play on the field,” says Bill Staples Jr., the chairman of SABR’s Asian Baseball Committee. “You can see it in the box score. Two passed balls in one game, then another, then another.”

It is a history of international ballplayers in microcosm. Clear communication portends success—its absence, failure. The Latinx boom of the 1960s and ’70s gathered momentum as more and more players arrived to help translate and facilitate one another’s learning English. When the Dodgers signed Hideo Nomo—the second Japanese big leaguer, three decades after the first, and the player who began the influx of Japanese stars—in ’95, his agent, Don Nomura, worked to ensure his client’s best outcome. “We had the leverage to say, ‘We want this,’ ” Nomura recalls. “I believed an interpreter was going to play a major role.” If you can’t communicate, he says, you can’t succeed.

At any given moment in an MLB game, there are more than enough ways to fail. The hitter can torque his hips too early or bring his bat to the ball at an angle removed, by some miniscule degree, from the ideal. The pitcher can fire a high-90s fastball—a marvel of balance and strength and bodily sync—but place it an inch or two to the side of where he intended. The base hit becomes an out; the strike becomes a homer. Games and careers take on different shapes.

Ask an interpreter about the most taxing part of their job, and they’ll dip into this mode of baseball cynicism. Jun Sung Park, a 30-year-old Korean Canadian who grew up playing hockey, is in his first year as the personal interpreter for Blue Jays ace Hyun Jin Ryu. Ryu has garnered Cy Young votes in each of the last two seasons on the strength of his strike-zone command, a puff-of-smoke changeup and obsessive preparation; the days before his starts involve protracted written proposals and counterproposals passed between him and pitching coach Pete Walker. Ryu understands conversational English and speaks some, but this work is granular, so Park translates each draft of each potential approach to each batter, Korean to English and back again. “A fastball in and a fastball off the plate in are two different pitches,” Park says. “If we want to throw a ball but [the catcher] is giving out signs to throw a strike, and if that becomes a hit or a run, it changes everything... That means I made a mistake that could cost us the game.”

Has he made such a mistake? “Not yet, and that’s how I plan to keep it.” Park employs the methods of a scholar preparing to defend a dissertation, scouring pages for any possibility of error or misunderstanding. “I’ll double-check, triple-check, quadruple-check if I have to,” he says.

Certain situations preclude such vigilance. Elvis Martinez, an interpreter with the Twins whose services are utilized by 14 Spanish-speaking players on the roster, remembers a recent visit to the mound alongside manager Rocco Baldelli. Right-handed reliever Hansel Robles faced a 10th-inning scenario rife with potential problems: runners on first and third, a speedster 90 feet from home, just one out. Baldelli quickly laid out plans: what they’d do in case of a bunt, how they’d handle an attempted steal of second. Around Baldelli and Robles, infielders frantically sorted out their own strategies, and the umpire began strolling over to break up the conference.

“I grabbed Robles on the shoulder and told him, ‘I’m here; just listen to me,’ ” Martinez says. “The situation is already stressful for him, and I don’t want it to be more stressful because he’s lost.” Robles got the batter out with a sinker that coaxed a do-nothing ground ball; he retired the next hitter with high heat. In recounting the outcome, Martinez slips into the first-person plural that interpreters use almost universally in describing the successes or failures of their players. “We were able to get out of the jam.”

Tasked with producing a Latin version of the Bible in the fourth century A.C.E., Saint Jerome wrote of the folly of literal translation, declaring that he would work “sense for sense, not word for word.” In its reliance on idiom and its multiplicity of meaning, the language of baseball rivals that of scripture, and its interpreters follow similar maxims. Martinez describes one in a seemingly infinite number of potential confusions. “Crowding the plate”—inching toward the strike zone—has no such meaning in Spanish. “If you translate it [directly], it doesn’t make sense in a baseball context,” he says. In such cases, Martinez errs on the side of specificity, describing the technique and its intended effect—taking away the pitcher’s comfort, or freeing up access to the outside edge of the plate—in detail. “The players know the baseball lingo...but we shouldn’t leave space for misinterpretation,” Martinez says. “Or the message goes missing.”

The ability to correct a misunderstanding, and even to sense when there’s a misunderstanding to correct, requires a fluency not only in the relevant languages but in baseball itself. MLB’s interpreters have gained and honed this knowledge in as many ways as there are members of their ranks. Martinez played middle infield at the Rochester Institute of Technology. Park translated corporate documents for Korean businesses opening branches in Canada before picking up a postcollege gig with the Korean Baseball Organization’s Kia Tigers; he spent his spare moments, as he still does, peppering hitting coaches and bullpen staffers with questions about nuances of hand placement and pitch shaping.

Two decades before he’d come to work with Ohtani, Mizuhara, who was born in Hokkaido but grew up in Los Angeles, fell in love with the game by way of another instant icon. “I was right in the middle of Nomo Fever,” says Mizuhara. “Ever since then, I just watched a lot of MLB.”

It is the fan’s dream: obsession maturing into livelihood. Mizuhara’s knowledge, accumulated over hours in front of the television, eventually took him from handling stock for an L.A. imports company to a job with the Hokkaido Nippon-Ham Fighters—where Ohtani played in Japan—translating for U.S. players. His capability there earned him a shotgun ride to the biggest baseball phenomenon in recent memory. Now he talks sequencing in pitching meetings; Nomo’s forkball has become Ohtani’s splitter. He translated the details of the team's hitting drill, designed to improve balance, timing and power, which coaches credit for his career-best year at the plate. Despite Mizuhara’s expertise, the education continues. On days when Ohtani serves as designated hitter, player and interpreter stand side by side on the rail of the dugout, tracing the patterns of the game. “He’s always asking me,” Mizuhara says, “ ‘What pitch do you think he’s gonna throw next?’ ”

The tutelage can be even more hands-on than this. Personal interpreters often shadow players from sunup to postgame—in some cases, they live under the same roof—and proximity compensates for whatever qualities they might otherwise lack as practice partners. Daichi Sekizaki, who works with Minnesota’s Kenta Maeda, began his MLB career with Yu Darvish: first as an assistant in Texas, then as an interpreter in Los Angeles and Chicago. (Darvish has since polished his English to the point that his Padres interpreter is functionally a safeguard.) Sekizaki had heard all about Darvish’s legendary arsenal—he put his own estimate, conservatively, at 11 distinct pitches—but didn’t fully grasp the extent of things until he was pulled into at-home throwing sessions. “He’s trying out new pitches, and they’re moving left and right,” Sekizaki says. He remembers closing his glove around a baseball that felt like a buzz saw. “To learn what true spin was—that was really shocking.”

Since then, Sekizaki has stayed attuned to what players can only show, not tell. During the season, he tails Maeda everywhere, from the weight room and treatment area to the outfield for long-toss and the bullpen for side work. “If he does conditioning, I do conditioning with him,” Sekizaki says. “If he’s running poles”—jogging foul line to foul line—“I’ll run poles. I’ll be able to get a better understanding of what he’s going through, how he’s feeling that day or on a certain movement. Then, if that’s something that he wants me to relate to the trainers, I can be the messenger.”

On a recent afternoon, as Maeda neared his return from a stint on the injured list with a pulled groin, he and Sekizaki competed in the Twins’ vertical leap test, a weekly ritual between the two. Sekizaki can jump well enough to push Maeda but had never beaten him, until now. He indulged in the rare victory over his much-better-credentialed workout buddy: “I jumped my all-time high,” Sekizaki says with a laugh. But he also, as ever, gleaned some parcel of information from it—about Maeda’s health, his comfort, the totality of his recovery—and filed it away.

In February, video of a speech from soon-to-be-ousted Mariners president Kevin Mather circulated. In it, next to admissions of service-time manipulation and broadsides fired at his own players, Mather criticized Hisashi Iwakuma, a former pitcher turned advisor to the club. “I’m tired of paying his interpreter,” Mather said. “Because when he was a player, we’d pay Iwakuma X, but we’d also have to pay $75,000 a year to have an interpreter with him. … His English got better when we told him that.”

Mather’s remarks emblematized a strain of resentment that still runs through the sport; midyear gripes about a slumping player’s purported unwillingness to learn English are a sports radio staple. But more and more clubs see interpreters as bastions of flexibility and interdepartmental knowledge in an increasingly impersonal atmosphere. Bryan Lee, Ryu’s interpreter through the 2020 season, was recently promoted out of the role and into the Blue Jays’ baseball operations department; Hideaki Sato, another onetime Darvish interpreter, now works in the same organization as an international scout.

It is easy to see why. Maybe no other job, short of a manager’s, requires so total a view of the player: as an athlete working to optimize his performance and as a person carrying doubts and discomforts. After Cleveland infielder Yu Chang made a throwing error that decided a mid-April loss, his social media accounts were targeted with racist messages. His teammates, manager and family rallied around him, but one pillar of support was Kuan Wu Chu. The two had met in 2017 in Akron, where Chu was working on a Ph.D. in chemical engineering, and Chang was playing for Cleveland’s Double A affiliate. Seeing a Taiwanese player in the system was a rarity, Chu says, and they became friends. “It’s a small town.”

Last season, Chu joined Chang in Cleveland, helping his friend through the vagaries of a young MLB career. He’s translated, yes, but also commiserated, celebrated and cooked with the ballplayer. In the days following the social media attacks, Chu offered a standard line of advice—“You can’t control other people, only yourself”—and made beef noodle soup and pork over rice. Appraising the legitimacy of the Taiwanese dishes, given the limitations of Ohio supermarkets, Chu echoes a sentiment he uses in describing his translation work. “I keep learning.”

Describing his own work in these heady days of Ohtani-mania, Mizuhara speaks in blissful quick tempo, the cadence of someone whose best-case projections have been realized. “I always remember how lucky I am to be in this spot,” Mizuhara says. “I’ve known Shohei since he was 18, and when I first saw him I was like, ‘Oh, my God, this guy’s unreal.’ ” That afternoon, Ohtani had inside-outed a fastball to plate two runs in a win against the division-leading Athletics and advance his own MVP case, and Mizuhara is still humming. “That’s got to be the best part of the job, just getting to be in the house and watch him do his thing.”

If that’s the best part, what is the most rewarding? Mizuhara’s tone changes, and he mentions long hours in the training room as Ohtani recovered from injuries in 2019 and ’20, passing phrases between player and staffer. “I got his groceries for him,” Mizuhara says. “He couldn’t move.” Then he talks about Ohtani’s arrival, in ’18, and a mission he assigned himself, unprompted by any team official. “The one thing I was focusing on in his first season—I had always heard that some Japanese players that came in the past could isolate themselves from the clubhouse. I didn’t want that to happen to him.” Mizuhara noticed the rest of the Angels playing a video game on their phones; at his behest, Ohtani downloaded it and joined in. It worked, Mizuhara reports happily. “We still play it all the time.”

More MLB Coverage:

• Tragedy and Hope: A Prospect, a Scout and a Pop Fly

• He Made Sticky Stuff for MLB Pitchers for 15 Years. Now He's Speaking Out.

• 'This Should Be the Biggest Scandal In Sports'