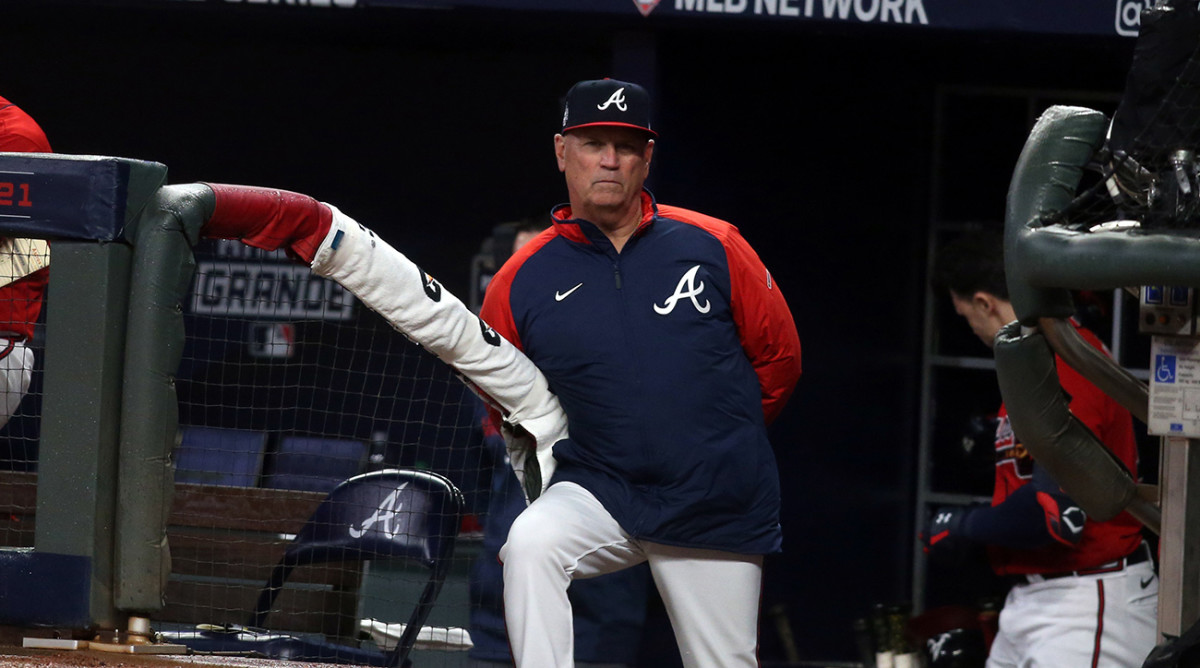

The Greatest Twenty-One Days of Brian Snitker’s Life

ATLANTA — Wardrobe needed a catcher’s mitt. It was the fall of 1987. A former minor league infielder named Ron Shelton was filming a baseball movie at Durham Athletic Park that revolved around a journeyman catcher. Someone rooted around the manager’s office at DAP, the one that summer that belonged to Brian Snitker, manager of the Durham Bulls, the Single-A affiliate of the Atlanta Braves. The wardrobe scout hit the jackpot: sitting there for the taking was the catcher’s mitt used for years by Snitker, a former catcher who had used the mitt as Braves bullpen catcher in 1985.

So it came to be that Crash Davis, the protagonist played by Kevin Costner in Bull Durham, forever on film uses the well-worn catcher’s mitt of Brian Snitker.

That is just about perfect poetry, for Snitker is the Crash Davis of managers. He has given the past 45 years of his 66-year-old life to the Braves as a player, coach and manager on various levels—most of which involved long bus rides and disappointments.

Bull Durham rings so perfectly clear that Crash Davis is one of the most quotable baseball personalities, real or imagined. There is one scene—on a bus, of course—in which Crash tells his teammates about the one time in his peripatetic career that he made the majors.

“I was in The Show for 21 days once,” he says. “Twenty-one greatest days of my life. You know you never handle your luggage in The Show? Someone else carries your bags. It’s great. You hit white balls for batting practice. Ballparks are like cathedrals.”

On Oct. 8, the Braves, making their fourth straight postseason appearance under Snitker, lost Game 1 of the National League Division Series to Milwaukee, 2–1. The next 21 days have been the greatest 21 days of Snitker’s life. His Braves are 10–3 in these three weeks, including 7–0 at home in which every game seems to be either an invitation for Costner to make another feel-good baseball movie or an apology from the baseball gods for putting Snitker through 44 years of broken transmissions and broken hearts.

Snitker can do no wrong. In World Series Game 1, he lost his starting pitcher, Charlie Morton, to a broken leg in the third inning—and won. In Game 3, he pulled his pitcher with a no-hitter intact and just 76 pitches—and won. On Saturday night in Game 4, he started a relief pitcher who had never started before, followed one out later by a starter used in relief, followed by four more pitchers—and won again, of course, 3–2.

Snitker’s Braves are the first team to win seven postseason home games while scoring five runs or less in each one. No other team had five such nail-biters in one postseason.

His team is only the fourth to win three World Series games with no starter lasting more than five innings, joining the 1929 A’s, the '47 Dodgers and the 2002 Angels (who had four such short-start wins).

Atlanta is Oz. All the BP baseballs are white. Nobody carries their own luggage. Truist Park is a cathedral in which prayers are answered. And every move the manager makes seems to jump off the page of the script of a winking Shelton. Twenty-one of the greatest days of his life later, Snitker is one win away from winning his first World Series.

“I don’t know if I’ll be able to sleep,” he says.

It would be the Braves first world championship since 1995, one that Snitker attended but only as an invited guest of the team. It happened during one of his purgatorial minor league assignments after the three times he was demoted from the major league coaching staff. When the last one happened in 2013, he accepted the likely possibility that he would never manage in the majors.

“And I was okay with that,” he says. “Each time they sent me down I knew I had done a good job.”

He signed with the Braves in 1977 and was cut by Henry Aaron four years later, though Aaron told him he was doing so because he would make a great coach and, someday, a great manager. It took him 35 years to get that big-league managing gig.

This year his greatest 21 days included not only the NL pennant but his son, Troy, a hitting coach with the Astros, winning the AL pennant. It was only the year before that each lost an LCS Game 7. On the eve of this World Series, Brian and his wife, Ronnie, ate dinner with Troy. On the first off day, they gathered for a family dinner in which they helped the grandkids carve pumpkins.

“It’s been about as perfect as you can get,” Brian says.

The same could be said for Snitker’s managing. He was not supposed to win Game 4, not after Dylan Lee, making his first career start, lasted one out. It was the 24th time a manager pulled his starter after one or no outs in a World Series game. Teams lost 17 of those previous 23 games.

With the bases loaded, Snitker gave the ball to Kyle Wright, who had never inherited a runner in his major league life. Cool as the autumnal Georgia night, Wright promptly retired the next two hitters with only one run crossing the plate.

Every choice Snitker made worked well. Wright, Chris Martin, Tyler Matzek, Luke Jackson and Will Smith allowed Houston one run over the final eight innings. The superb bullpen held the game in check until Dansby Swanson and Jorge Soler— Snitker’s right-handed pinch hit choice against righthander Cristian Javier, natch—hit back-to-back homers in the seventh for another Snitker-doodle of a win. Soler had been hitting .180 this year against right-handed breaking pitches.

How in the world does Snitker do it?

“Because he allows us to be us,” Swanson says. “I can’t say it enough. He allows each guy to be himself. He trusts us. He trusts us to do our preparation. He knows we do our work in the cage. He knows we do our stuff when it comes to studying pitchers. He knows we do our defensive work with Wash [coach Ron Washington]. He trusts that and allows us to go play.

“You know, so many times in this day and age, it’s so much about numbers, this and that. But he trusts us to go out there and do what we do. And that’s why we win every day and that’s why we are who we are. Having the confidence of somebody like that is huge.”

Despite all the miles logged on buses, Snitker is a modern manager. When GM Alex Anthopoulos said in mid-May he wanted the Braves to start using more defensive shifts, the Braves went from dead last in shift use to No. 2 in the majors. Snitker admitted his pulling of Ian Anderson after five no-hit innings in Game 4 might not have happened two or three years ago. He has switched from a proponent of NL rules to the universal DH.

Most importantly of all, he has licked the toughest assignment a manager has in today’s game: run an efficient bullpen without wearing out his arms. Snitker has made 58 pitching changes this postseason. Only one has resulted in a loss. His relievers are 7–1.

Tonight, Snitker will try to grab that World Series title that has been 45 years in the making. He has been a minor league manager (19 years), a major league coach (11), a major league manager (six), a minor league coach (five) and a minor league player (four). Major League Baseball is about stars. Stars such as Freddie Freeman, who also is trying to win his first World Series. Stars people follow with such fervor that adults wear jerseys with the player’s name on them, as if appropriating a residue of their success and fame for themselves.

But people like Snitker are the true mortar of baseball—with a small “b.” They ride the buses and break their backs because they not only love the game, but also pull unseen joy from providing even the smallest bit of help to nurture the dreams of the many young men who want to be the best ballplayer they can be.

Tonight, Snitker gets a chance to be historically famous after all these years. He’ll have to manage another bullpen game, which is the way it should be. His bullpen has been fantastic.

“It’s why we treated them right during the year,” he says. “We hardly used them three days in a row except Will, and he’s the closer. And if we did, we gave them two days off. We did it so that we can use them now. We did it to win these games.”

Few men have given so much to one and only one organization. “When I see the Braves’ logo,” he says, “I get emotional about it.”

He has given 45 years, summers away from his family, buckets of sweat equity, and a favorite old broken-in catcher’s mitt. He never did get that mitt back from Costner.

More MLB Coverage:

• Pearls Before Swing: Meet the Man Behind the Joctober Bling

• Soler's Go-Ahead, Pinch-Hit Home Run Shows Value of the Even Man Out

• Missed Opportunities in Game 4 Puts the Astros' Season On The Brink

• Why Does MLB Still Allow Synchronized, Team-Sanctioned Racism in Atlanta?