Dues Paid in Full, the Braves Are World Champions

Baseball is a cruel, fiendishly inequitable dues collector. The payment it requires before doling out rewards follows whim more than logic.

There is no other way to explain why Braves pinch runner Terrance Gore has three World Series championship rings and one career RBI. Or why Jorge Soler, hitting .192 on a last-place Royals team July 29, finds himself three months later with a World Series MVP trophy and a second championship ring to complement his 2016 Cubs bauble.

Get SI’s Atlanta Braves World Series Champions commemorative issue here.

This same game, however, makes Freddie Freeman, one of the league’s purest hitters and most upstanding people, log 15 seasons in the Braves’ organization, including three straight 90-loss seasons, before getting to a World Series.

There is also Braves coach Ron Washington, who had spent more than five decades in pro ball without a World Series ring, including one time as Rangers manager in 2011, when he was one strike away from a title three times.

There also are Braves fans, who endured watching their team knocked out of 16 straight postseason appearances without a World Series title, an unmatched record of sustained futility.

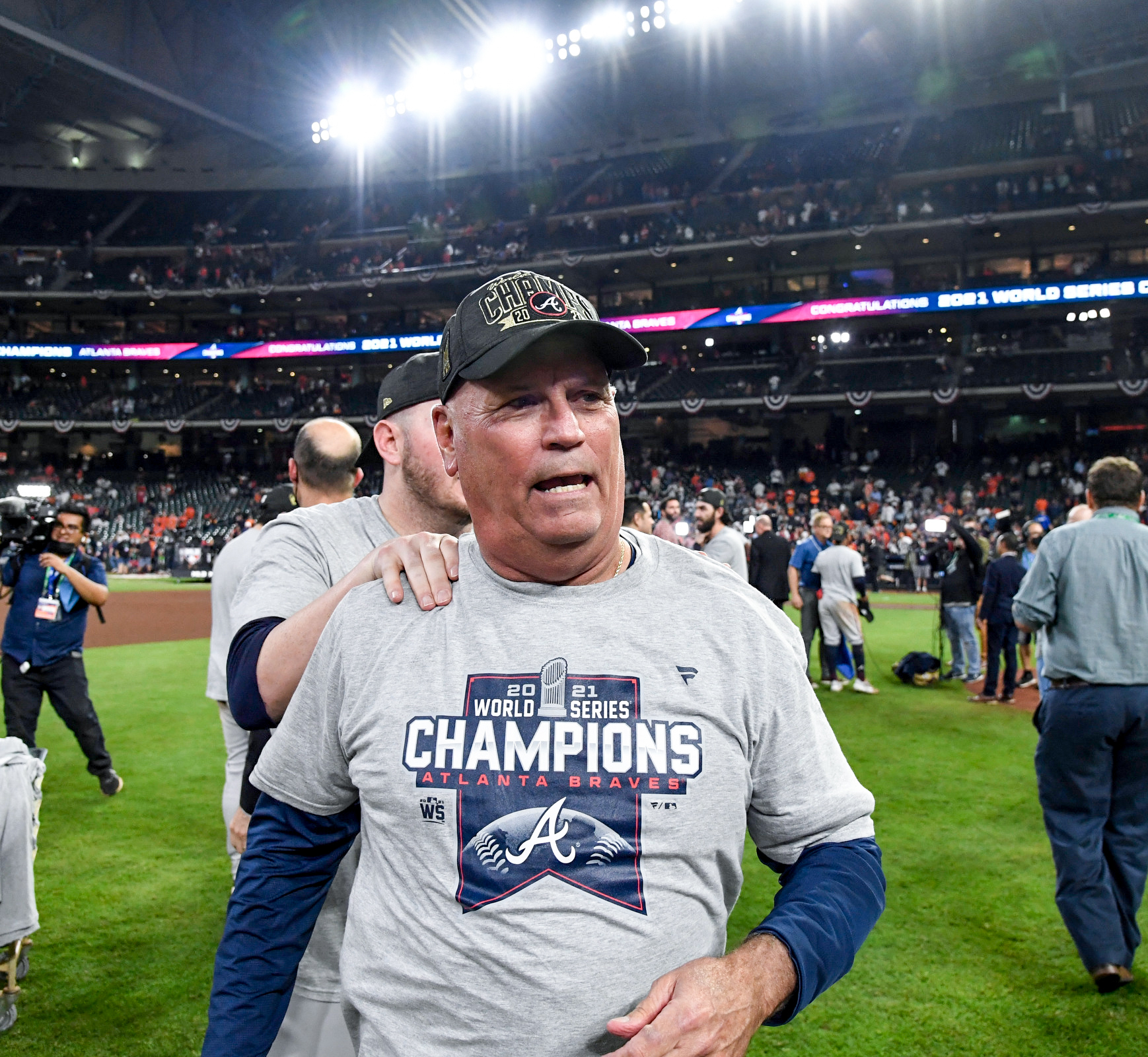

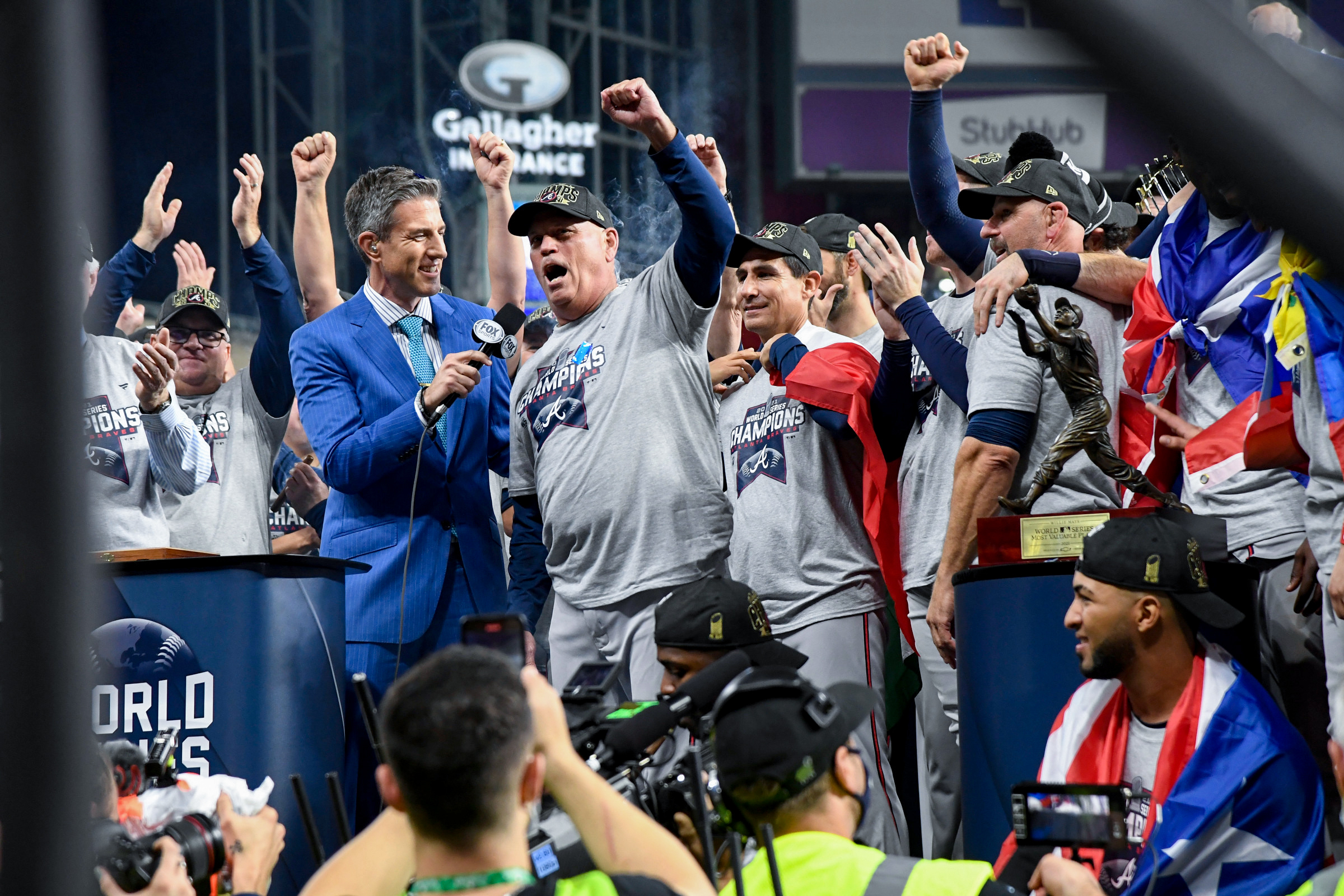

And then there is Brian Snitker, the Atlanta manager who doubles as the patron saint of dues paying. Snitker has devoted 45 years of his life to the Braves, most of it ingloriously, such as thrice getting demoted from a big league coaching job—once so shockingly undeserved that he nearly quit the game he loves—before finally reaching the World Series this year. When you ride buses as much as Snitker did, you learn important lessons, such as not to drink the beer on those buses.

“I learned, because then you have to go to the bathroom,” he says. “And on minor league bus rides guys are sleeping everywhere. They are sprawled across seats. They’re sleeping in the aisle. They’re sleeping in the luggage racks. My goodness, you are stepping on people in the dark to get to the bathroom in the back. So I stopped drinking on the bus.”

Such are the lessons of an earthy, humbled soul. Forty-five years sometimes seemed like a longer version of the 10-hour bus ride from Savannah to Memphis when Snitker was playing in the Southern League in the 1970s. Snitker and the Savannah Braves traveled on a yellow school bus with no air conditioning. There was no professional driver. The team trainer drove the bus, though sometimes a roving instructor such as Cito Gaston would get behind the big wheel to give the poor trainer a break. Snitker can still feel the rivets in the metal, unpadded armrests pushing mockingly into his skin, as beads of sweat gathered and dripped in ceaseless protest to the hot, thick Southern evening air found intolerable by all life forms but gnats and mosquitoes.

“Oh, no, there’s nothing fair about it,” says Ronnie Snitker, Brian’s wife, about this great game of baseball. “But you just have to keep taking your lumps and go through it.

“And look what we did.”

Lookee here. Freeman, the Braves, their fans and most of all Snitker finally are deemed to have paid their dues in full. For the first time since 1995, the Braves are world champions. They overwhelmed the Astros, 7–0, Tuesday in Game 6 to finish a dominating World Series. They outhomered Houston, 11–2, while holding the game’s highest-scoring team to a .224 average and 3.33 runs per game.

This championship is a triumph of perseverance, if nothing else. The Braves never even had a winning record this year until Aug. 6.

“Back in June or July it would have been absurd to say we would be the last team standing,” says bench coach Walt Weiss. “But Snit, he’s a calming influence. He shows up the same way every day, regardless of the circumstances. He’s just the calming presence of this team. It trickles down to the players. They see him always in control.”

Championships are never so sweet as to when they are a generation or more in the making. Euphoria seems brand new, even to the elders, and it is literally so in the case of someone who was born in Kennesaw, Ga., a year before the Braves last won a title and grew up rooting for the team that would go 0-for-16 in the postseasons of his remembered life. On Tuesday night that Marietta-raised kid, shortstop Dansby Swanson, hit a home run and fielded the last out of the clinching game of his hometown team’s title. He threw the ball to Freeman, who has been around so long he played for Bobby Cox and with Chipper Jones, and who also hit a home run in the clincher. Of course.

These generational titles are becoming the norm. Baseball, the great dues collector, is going soft. This was the sixth title out of the past seven that was 25 years or more in the making. The Braves (26 years) followed the Dodgers (32), who followed the Nationals (50), whose title followed two years after the Astros (55), who followed the Cubs (108), who followed the Royals (30). And it happened in a year in which Braves legend, Hall of Famer and Snitker good buddy Henry Aaron died.

“Hank would move us around and put us in places he thought would best benefit the organization,” Snitker says of the minor league staff when Aaron ran the farm system. “Nobody ever wanted to let Hank down. That’s just kind of the way it was. We didn’t want to let him down. He charged us with responsibility to make these guys better, and we weren’t going to let him down.”

The spirit of Aaron not only still exists within the Braves’ organization; rather, his spirit is the Braves’ organization.

Lewis Carroll’s Alice had gone through the looking glass when she encountered the Queen of Hearts. The Queen tells Alice about the “very good jam” she can’t have.

“Well, I don’t want any today, at any rate,” Alice says.

“You couldn’t have it if you did want it,” the Queen tells her. “The rule is, jam tomorrow and jam yesterday—but never today.”

Alice pushes back. She says it must be “jam today” some time.

No, the Queen says. It’s jam only every other day, and today is never any other day.

It is Catch-22 before Catch-22. It is the quintessential tale of the cruelly unrewarded, rigged life. The game is full of hard-working people like Snitker, for whom it never seems to be “jam today.” So when they finally get their jam, the reward of the World Series never seems greater.

Snitker was a .254 hitting backup minor league catcher in the spring of 1981 when Aaron called him to release him. But there was another reason for the call: Aaron thought Snitker would make a good coach and manager someday. He offered him the job as pitching coach for the franchise’s rookie league team in Bradenton, Fla., where Aaron’s son Lary and the son of the late Braves GM Bill Lucas played. The next year Aaron gave Snitker his first managing gig, in Anderson, S.C.

Back in those years, Snitker would play racquetball with Aaron in spring training at a local YMCA in Florida.

“I probably still have [marks] on the back of my legs,” Snitker says, “because if you got in front of him—you talk about wrists and hands—that freaking racquetball would go right through you, and he didn’t care. After a while I learned to stay the hell out of his way.”

Snitker was promoted to the major league staff in 1985 as bullpen coach, only to be sent back down the minors to manage in ’86. He returned to the big leagues as coach in ’88, only to be demoted again in ’91. Snitker was in the minors when the Braves played in the ’91, ’92, ’95, ’96 and ’99 World Series. Back up as third base coach from 2007 to ’13, Snitker was demoted a third time after that run.

“Recycled, I call it,” he says.

He had just turned 55 years old when general manager Frank Wren told him after the Braves lost the 2013 Division Series to the Dodgers that he was being reassigned to manager of Triple A Gwinnett. So hurt was Snitker that he contemplated quitting the Braves over that weekend.

“I wasn’t really O.K. with that one,” he says. “But what are you going to do? I wasn’t at an age where I was going to pack up and start somewhere else. That was a tough one. I had to sit there for a couple of days and make a decision—about whether I wanted to go on or not. To keep grinding. I don’t know how to do anything else.”

Says Ronnie, “It was very difficult because we had just come back from L.A. and felt we did a great job there. We just didn’t make it all the way. So we were happy with the season. And then to hear we had to go back. … It was back home, right there in Gwinnett, near our children and right down the street from our house, but it was the one time where he thought, Maybe this isn’t going to happen.

“I used to always say he will manage in the big leagues one day, but after that it was kind of Maybe not.”

Brian told Ronnie he had no idea what he might do next if he quit. The couple had two children, Troy and Erin.

“I told him I would go back to work,” Ronnie says. “He would stay home and take care of the kids, like he did every offseason. Every year he would get ready to go to spring training and say to me, ‘Do you know how to make the sandwiches? And the lunch?’ Because he was Mr. Mom in the offseason. I went to work in the offseason, and he took care of the kids.”

Snitker decided to stick it out.

“It’s like I had invested too much into this thing to walk away from it,” he says.

“We made it through that weekend,” Ronnie says. “It was rough. But we made it through the weekend. And we decided to stay with our family. We couldn’t imagine being anything other than Braves. I don’t know what my children would have done.”

Snitker managed three more years in the minors, bringing his investment in playing, coaching and managing in the farm system to 38 years—nearly half his life—when the Braves hired him in 2016 as a first-time manager at age 61.

“Every year for 16 years I would say goodbye to my family in February and I wouldn’t come home until September,” Snitker says. “Ronnie did an amazing job keeping the family running.”

Snitker managed in 11 minor league towns, including Durham, N.C., in 1987, the site where Bull Durham was filmed. Kevin Costner, while portraying Crash Davis, the movie’s minor league journeyman and protagonist, used Snitker’s well-worn catcher’s mitt.

“Not only that,” says Troy, “in the opening scene of the movie, they show Susan Sarandon’s house, and there’s a baseball card in her mirror. That’s my dad on that baseball card. Pretty cool.”

Troy, now the Astros’ hitting coach, was born the next year, in December. Erin was born the previous year, 1986, also in December.

“Not an accident,” Brian says with a laugh. The Snitkers planned their family around baseball season.

Snitker was nervous before Game 6. It was the first time all postseason he didn’t come to work with that calming presence Weiss raved about. He was quiet and a touch jittery.

“I was nervous,” he says. “More so than the other day [in Game 5], when we were home with a chance to clinch and didn’t do it. I was so in tune with what we had to do that day and piece that thing together I didn’t have time to be nervous.

“I’ll be honest: my stomach was turning a little bit today.”

Before Game 5, Snitker said he was “blown away” by the many people who had reached out to him during the series to wish him luck, including former managers Joe Torre and Jim Leyland.

“It’s … touching,” Snitker says with a tear in his eye.

Then in Game 5, Snitker’s team became the first to blow a four-run lead at home in a World Series potential clincher. He had an off day to marinate on that loss, as well as what might happen if the Braves took a two-game losing streak into a Game 7.

“It’s been a lot physically and mentally,” he says. “It’s been tough getting here. You’re on ‘go’ for over a month. It seems like the Milwaukee [division] series was last year. Every game is an emotional game. You get to bed at 4, get up at 10, grab a cup of coffee and you do it all again.”

After the Game 5 loss, Snitker made a change to the team’s itinerary. He pushed back the bus to the airport for the flight to Houston by several hours. The three games in Atlanta were played mostly in cold, damp conditions. He sensed the games took a toll on his players, so he arranged for them to get more sleep.

It had been that kind of year for Snitker and the Braves: a series of calamities, each met with calm and resourcefulness. The entire Opening Day outfield was lost: Marcell Ozuna to administrative leave after a domestic violence charge, Ronald Acuña Jr. to a knee injury and Cristian Pache to a feeble bat. But after GM Alex Anthopoulos traded for Soler, Joc Pederson, Eddie Rosario and Adam Duvall in July, the four horsemen hit more home runs (59) than any trade acquisitions in history surpassing the 54 by the pickups of the 1951 Athletics.

The Braves also lost pitcher Mike Soroka to an Achilles injury and World Series Game 1 pitcher Charlie Morton to a broken leg. Snitker responded by becoming the first manager to start rookies on the mound in three straight World Series games. Actually, the assignments of Dylan Lee and Tucker Davidson—together they had seven MLB career games and no wins—were not made until the mornings of Games 4 and 5, making Snitker unofficially the first manager to use “TBD” for World Series starting pitchers on back-to-back days.

Of his Game 6 starter, Max Fried, Snitker was not only more certain of the assignment but also more confident.

“I had a lot of confidence in Max,” Snitker says. “Just from the last couple of days on the bench, and listening to him, I had no doubt he was going to show up.”

Just before Fried left the clubhouse to warm up for his start, pitching coach Rick Kranitz cornered him.

“Give me 30 seconds,” Kranitz said.

Kranitz had remembered his first conversation with Fried in a phone call a few years ago. He remembered how Fried told him, “I need to be athletic when I pitch.”

Fried is a terrific athlete, a good fielder, who needs to feel fluid on the mound, not mechanical. He had bombed his Game 2 start, largely because he abandoned his fastball. Fried threw the pitch only 24% of the time in Game 2, the second-lowest serving in his 86 career starts, postseason included.

“Max, be who you are. It’s good enough,” Kranitz told him. “Be athletic. Let your natural ability take over.”

Fried came out blazing. He threw 75% fastballs to cover the first three innings, including a 98.4 mph bolt to fan Yuli Gurriel that was the third fastest pitch among his 4,244 career fastballs. He also whiffed Carlos Correa on a 90-mph slider.

“Those were some of the best pitches I ever saw the young man throw,” Kranitz says. “When I saw that 90-mph slider disappear, I knew at that point, This dude is ready to go. He’s good. He’s got it.”

In the middle innings Fried dazzled the Astros with his changeup. He threw 11, his most in a game in four years, and all of them from the fourth through sixth.

“Max is very smart,” Kranitz says. “He did not pitch his game last time. He wants to get all of his pitches involved. That’s exactly what he did this time. He’s got such belief in what he’s doing and is so smart, he’s one of the best I’ve ever had about game-planning himself. He knows exactly what he wants to do.”

Says Snitker, “I told Freddie, ‘I think he’s reinventing himself out there,’ I think he was pitching with whatever he had going.”

Snitker pulled Fried after six innings in which the lefty allowed no runs, no walks and only four hits. He joined Ralph Terry of the 1961 Yankees as the only starters to win a World Series clincher with no runs or walks and so few hits. In a postseason in which starters were 14–21 and averaged 3.89 innings per start, Fried’s bit of old-timey pitching seemed stunning in its length and effectiveness.

With 74 pitches, Fried could easily have continued, but Snitker deployed Tyler Matzek and Will Smith to finish, because they have been freakishly tough to hit. Since June 25 hitters have gone 1-for-45 against Matzek’s 221 sliders. Smith completed a flawless postseason in which he pitched one scoreless inning for the 11th time in 11 outings.

So good was Fried that the game essentially was over when Soler demolished a pitch from Luis García over the train tracks in left field at Minute Maid Park for a three-run homer in the third. Anthopoulos never expected Soler to be this good. When he obtained Soler from Kansas City, he told Snitker, “I got you a right-handed bat off the bench.”

But when hitting coach Kevin Seitzer watched video of Soler’s recent at bats, he shouted for Weiss to come quickly and take a look himself. The two coaches then ran to Snitker’s office and said he had to go tell Anthopoulos that Soler was too good to be limited to “a right-handed bat off the bench.”

“His pitch recognition is so good,” Freeman says, “that sometimes when he’s hitting and I’m on deck I hear him yell, ‘No,’ just as he takes the pitch.”

Soler hit three go-ahead homers in the series. In doing so he also became the first in a World Series to hit a leadoff homer (Game 1) and a pinch-hit homer (Game 4).

By the time Smith took the ball for the final three outs, the Braves led 7–0. Snitker was still nervous.

“I know Will’s got a seven-run lead, and he’s been lights out,” Snitker says, “but it’s still baseball. I’ve been bitten on the rear too many times to take anything for granted or look ahead.

“I didn’t allow myself to think ahead because I know how fragile and how hard it is to win a baseball game. Up 3-[games-to]1, we’ve been through it. We lived it last year. We found out how hard it is to win a game.”

Smith threw a fastball. Gurriel hit a grounder to shortstop. Swanson, the kid from Marietta, scooped it up and looked to throw to Ozzie Albies at second base for the final out. But Albies was late getting to the bag. Swanson audibled and fired to first base, into the championship’s fitting final resting place, Freeman’s mitt.

“I was sitting there just trying to keep myself together,” Snitker says. “Then the guys mobbed me. And then the emotions came. I thought about Ronnie and the kids and everything they’ve been through. If it wasn’t for them, I wouldn’t be able to do this. After that last out, it all hit me.”

Almost 30 minutes after the game, Ronnie still had a hard time finding the words to describe what had just happened.

“I don’t have any more words,” she says. “I just have tears.”

Ronnie and Brian met in the early 1980s, when Brian was a roving instructor in the minors and rooming with Gaston. It was a friend of Gaston’s who set them up on a blind date.

“We watched Monday Night Football,” Brian says, “and fell asleep.”

Ronnie was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1993, just two weeks after Brian’s father, Richard, a former traveling salesman for Pabst beer and Jim Beam, died from a massive heart attack at age 73. That year marked another time in his journey that Snitker was demoted: yanked from managing Class A Macon for being too tough on young players and assigned to being a roving coach that year. More dues to pay.

Now Snitker is a grandfather three times over. Ronnie was holding the youngest grandchild, Hank, Erin’s son, who was asleep.

“He’s a grandpa’s boy,” Ronnie says. “One of his first words was ‘Grandpa.’ Tonight he saw his grandpa on TV and he just screamed with delight.”

Grandpa Brian is the oldest first-time winning manager of the World Series except for Jack McKeon, who was 72 when his Marlins won in 2003. But McKeon was hired during that season as a replacement for the fired Jeff Torborg.

The Braves were 55–55 on Aug. 5. They won the next day for their first winning record in 111 games. It began what turned out to be a 44–23 finish. That’s where the beauty of this team will be misremembered. Such a finishing kick is the shorthand story of the 2021 Braves. Their lineup in the clinching game included the four horsemen who were elsewhere at the All-Star break. They will stand as a lesson that World Series titles can be won in July in the days leading to the trade deadline.

But to understand the true lesson of this team you must go back to 2015 to ’17, when Freeman, a second-round pick in 2007, played on teams that over three seasons lost 278 games and finished 74 ½ games out of first place. You must go back to the 16 postseasons of futility, which included a record of 9–12 in potential clinchers. You must go back to places such as Durham, N.C.; Macon, Ga.; Danville, Va.; Sumter, S.C.; Jackson, Miss.; and all the many locations on a minor league map connected by blue highways and yellow buses, not just for Snitker but for all the lifers who keep paying their dues out of an obligation to their love of baseball.

These Braves are about the long haul, about honoring what Henry Aaron stood for and the kind of religious faith that the game will do right by you if you just keep at it. In that opening scene of Bull Durham, with a Brian Snitker card tucked into the frame of Annie’s mirror, Savoy says, “It’s a long season and you gotta trust it. I’ve tried ’em all. I really have. And the only church that truly feeds the soul—day in, day out—is the Church of Baseball.”

No matter how faithful, not all journeys are rewarded with a World Series title. Sometimes the Queen of Hearts holds cruelly to jam tomorrow and jam yesterday but never jam today. As Ronnie says, all you can do is take your lumps and keep going. And if there should come a day like World Series Game 6, when all dues are paid in full, the jam today is never so sweet.

More MLB Coverage:

• Fried Finds Another Level to Win One for the Braves and Starters Everywhere

• Three Thoughts From Atlanta's World Series Win

• Astros Couldn't Silence the Naysayers—and Never Will

• Brian Snitker Is Old-School. He Doesn't Embrace Analytics. And He's Thriving.

Get SI’s Atlanta Braves World Series Champions commemorative issue here.