One Contender Will Be Hurt More Than the Rest by the Defensive Shift Ban

The Dodgers’ secret sauce is off the menu for this season.

While the ban on defensive shifts is great news for hitters, especially left-handed hitters, it’s bad news for Los Angeles, which enjoyed an edge over the rest of baseball for the past four seasons with how well it deployed extreme defensive positioning.

No team since 2019 shifted more often and more effectively than the Dodgers. That edge goes away now that all teams must position two infielders on each side of second base and no deeper than the infield cutout, which is 95 feet from home plate.

“Not shifting will definitely have an effect but it is still all relative,” says Andrew Friedman, the Dodgers’ president of baseball operations. “The gap might not be as large between the best and worst team as it has in the past.

“That said, some of it is prioritizing good defenders as well as generating weaker contact [last point is my intuition]. Also, some portion of that comes from outfield positioning, which remains unchanged.”

Friedman is baseball’s Secretary of Defense. With the Rays, he and manager Joe Maddon were early adopters of shifts. In a three-game sweep of the Yankees to open 2012, for instance, the Rays caught so many line drives that New York hitting coach Kevin Long scoffed, “They’re not above the game by any means. They hit the jackpot against us in the first series ... They were in the perfect spot. Come on, man. That’s not going to happen all year.”

It did. The Rays led the major leagues in lowest batting average allowed on balls in play.

After Friedman left to run the Dodgers in 2015, he used their enormous resources to elevate the art (and science) of the shift. Here are the best teams in baseball at turning balls in play into outs over the past eight seasons (when Friedman has been running the Dodgers) and in the seven seasons prior (when he was running the Rays). Friedman is the common denominator.

Watch MLB with fuboTV. Start your free trial today.

Lowest BABIP Allowed

Year | Team | BABIP | MLB BABIP | Next Lowest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2015-’22 | Dodgers | .272 | .296 | .286 by Houston & Tampa Bay |

2008-’14 | Rays | .282 | .298 | .286 by Oakland |

At each stop, Friedman’s teams have created a significant edge by taking away hits with how well they play defense, especially with their positioning. You must start with this: a large part of that success is the quality of their pitching. Weak contact is easier to defend than hard contact. Fly balls are easier to defend than ground balls. Since 2015, the Dodgers have allowed an MLB-low batting average of .224. Their expected batting average allowed is .223. Only four teams have a lower delta between batting average and expected batting average in that time: the Cubs (-.004), A’s (-.001), Cardinals (0) and Guardians (0).

Yes, the Dodgers have very good pitchers. But the amount of time and resources they devote to positioning has been industry leading. Los Angeles was one of the first teams to deploy laminated defensive positioning “cheat sheets” for fielders to keep in their back pockets. The cards are specific to each pitcher and are swapped out upon each pitching change.

In 2016, the Mets complained to MLB that the Dodgers used laser-guided measuring devices before a game at Citi Field to assist with their defensive positioning. MLB said the use of such devices was illegal only with in-game use.

The Dodgers have been the best at defensive positioning even though they have not had many superior defenders. They won the World Series in 2020, for instance, often with Corey Seager at shortstop, Chris Taylor at second base and Max Muncy at third base. In Friedman’s time with the Dodgers, only two Los Angeles position players have won a Gold Glove: outfielders Mookie Betts and Cody Bellinger.

Los Angeles took a big leap forward with its defensive strategies in 2019. Look at how the Dodgers under Friedman rose to the top of the pack as they shifted more:

Dodgers Defensive Ranks Under Friedman

Year | D. Efficiency | BABIP | Shift % |

|---|---|---|---|

2022 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2021 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2020 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

2019 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

2018 | 8 | 6 | 10 |

2017 | 1 | 3 | 13 |

2016 | 5 | 4 | 17 |

2015 | 12 | 14 | 24 |

That is a serious upgrade. The more the Dodgers shifted, the better they played defense. How much better? Here’s a look at the best and worst teams over the past four seasons at defending balls in play—and how shifts played a part in their strategies:

Lowest BABIP, 2019–’22

Team | BABIP | Shift % Rank |

|---|---|---|

1. Dodgers | .263 | 1 |

2. Astros | .274 | 2 |

3. Cardinals | .280 | 26 |

Highest BABIP, 2019–’22

Team | BABIP | Shift % Rank |

|---|---|---|

30. Red Sox | .319 | 23 |

29. Royals | .309 | 25 |

29. Rockies | .309 | 30 |

The Dodgers and Astros were defensive wizards when it came to positioning (behind terrific pitching, of course). The Cardinals relied more on fabulous defenders than shifts. On the negative side, the Red Sox play in a hitter’s park and have long been poor at interior defense, the Royals probably should have been shifting more in a big ballpark and the Rockies just have too much acreage to cover at Coors Field to ever be a great defensive team.

What really jumps out is how much better the Dodgers are than everyone else, even the Astros. Shifts are designed to take away hits on hard contact. The Dodgers became superb at it once they went all in on shifts in 2019, as this chart proves:

Ground Balls Hit 95+ MPH vs. Dodgers

Year | No. | Hits | Avg. |

|---|---|---|---|

2018 | 505 | 205 | .406 |

2022 | 490 | 164 | .335 |

The Dodgers should have yielded 199 hard-hit ground-ball hits last season if they played the same way they did in 2018. Instead, their shifts and positioning took away 35 such hits. Those hard-hit ground-ball hits are coming back this year. As Friedman points out, the ban on shifts cuts the gap between the best and worst defensive teams. That’s where the edge is lost.

Further, the Dodgers have an unsettled infield situation. Their presumed shortstop, Gavin Lux, blew out his knee in spring training and is out for the year. Their most used middle infield is expected to be shortstop Miguel Rojas, a 34-year-old who has never started more than 132 games at the position, and second baseman Miguel Vargas, a bat-first rookie.

Without shifts, the overall MLB batting average is bound to rise, perhaps by as many as 15 points. Last year it was .243, the worst since the all-time low in 1968 sparked massive rule changes (lowering the mound, redefining the strike zone).

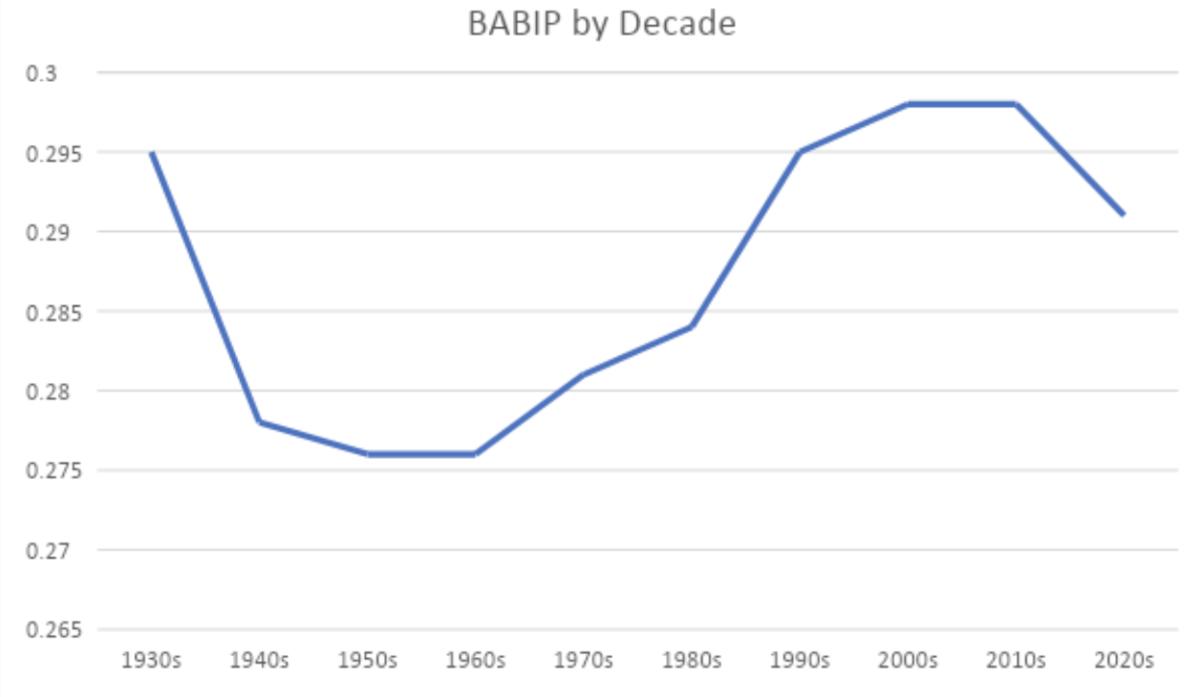

Shifts have been banned for one reason: they worked too well (despite your consternation on a few mis-hit, opposite-field balls that would otherwise be outs). They worked so well that three years of this decade produced the first downturn in BABIP in seven decades:

Back in the halcyon days of the shift, in 2018, the Brewers confidently fielded what they called their “offensive line” infield: first baseman Jesus Aguilar (277 pounds), second baseman Travis Shaw (230), shortstop Jonathan Schoop (247) and third baseman Mike Moustakas (225). They just let those guys mash at the plate knowing that finely tuned shifts covered for their lack of range on defense.

Those days are over. The world of defense has been flattened. The Dodgers’ edge has been dulled. In this new world, range and athleticism trump front-office intellect.