Will Home Runs Rain Down in Seattle During Derby?

“It’s a Cinderella story,” says Ted Buehner. One he considers a life home run of sorts. One that even led to a major Major League Baseball event taking place in Seattle this week.

Buehner tells the story in—what else?—a coffee shop, over a cup of the caffeinated stuff; “water” to the locals. He was in grade school, growing up in the Portland suburb of West Hills, when the squall started, when it grew in size and elevated in intensity. It would later be known as The Columbus Day Storm, or The Big Blow. It’s the strongest non-tropical windstorm to ever hit one of the lower 48 states. And oh, boy, did it hit.

In 1962, it wiped out power from the San Francisco Bay to Vancouver, Canada; winds whipped into the Washington and Oregon coasts in excess of 150 mph, as fierce as a Category 3 hurricane. This storm ripped homes from their foundations, destroyed property up and down the west coast, wrecked thousands of commercial buildings, toppled every tower in sight, blew more than 11 billion board feet of timber all the way to western Montana, injured hundreds and killed at least 46. But where most young children fell somewhere between blissful oblivion and abject terror, Buehner considered something else. A career path.

“As a 6-year-old, that’s what sparked my interest [in the atmospheric sciences],” he says. “I wanted to know why.”

He would soon dabble in weather forecasting, because of what that storm had sparked inside him. In high school, he taught the weather portion of earth science class. He enrolled in college at Oregon State, graduated with a degree in atmospheric science, started a job at the National Weather Service in 1977 and then worked there for 40-plus years.

Over those decades, Buehner came to agree with the popular view regarding the moment extreme weather pointed him in the direction he has followed ever since. That storm was the perfect storm.

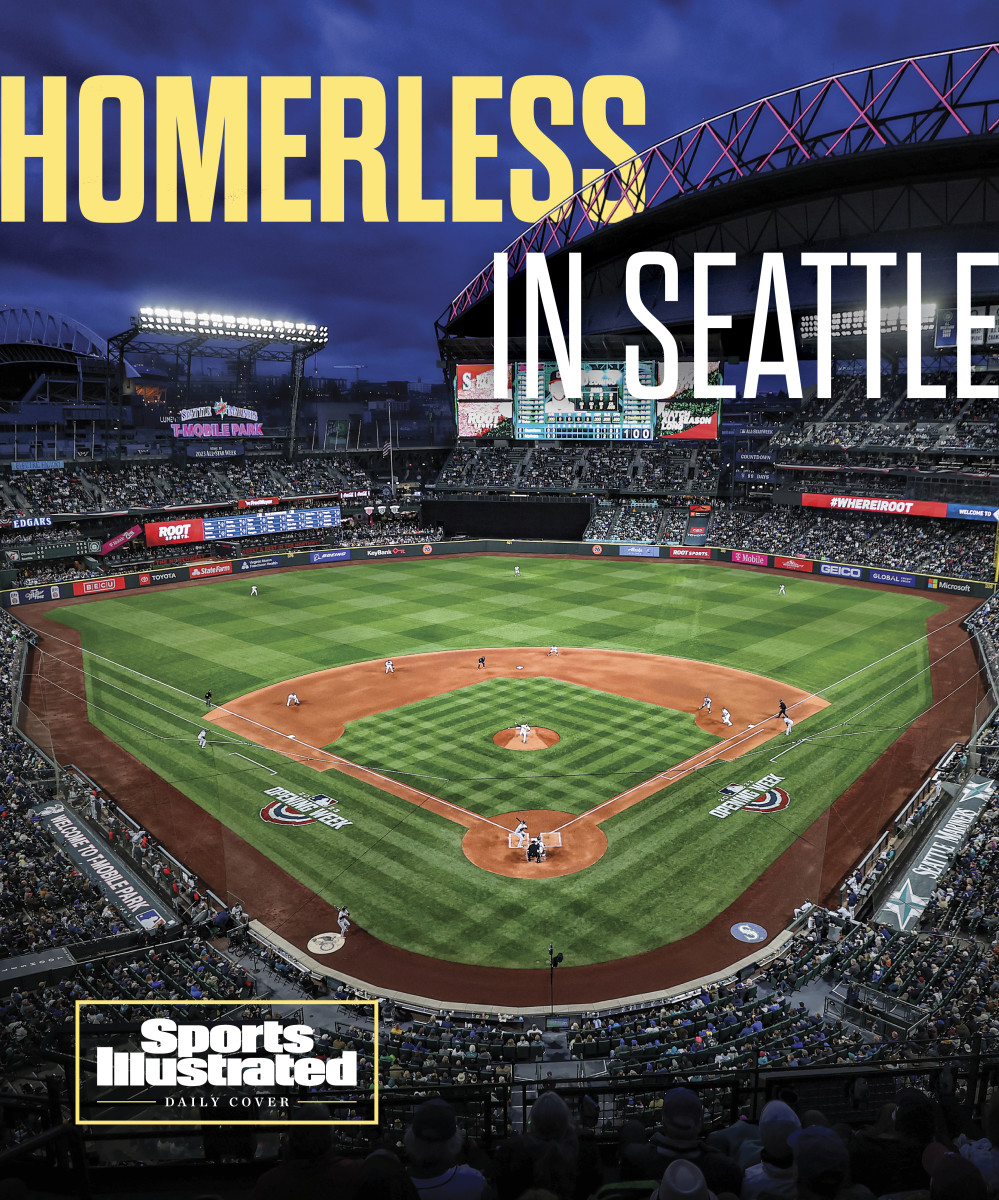

His life is pretty much that, too. And, as it happens, Buehner’s perfect storm even ties to Monday, when MLB’s Home Run Derby will unfold a short drive south from his suburban home. The derby, of course, is a seasonal highlight for sports fans, a night when baseball’s best and beefiest long-ball launchers do nothing but crush high-arcing shots skyward. T-Mobile Park, of course, is also a stadium where, conventional wisdom suggests (along with some historical data), home runs are swallowed and spit back onto the field. Which leads to perhaps the most odd juxtaposition in derby history.

Will Monday night mark the most boring iteration of a competition built with excitement at the forefront? Or will it deconstruct some myths about offensive baseball in Seattle?

That’s why we went to Buehner, who’s now known across the region by the nickname his college buddies bestowed upon him for their long-running fantasy football league. Who better to explain all this than … Tornado Ted.

If the history of MLB’s Home Run Derby is any indication, the tens of thousands who will descend on T-Mobile Park on Monday night, not to mention an international television audience, have little reason for concern. Tornado Ted suggested looking up the numbers and the format changes to compare and contrast. So we did that, too. In TT we trust.

The endless changes to the derby’s layout are less relevant than the tweaks from 2015 to now (although, it’s hard not to love The Golden Ball experiment in ’05 and ’06). The latest derby iteration came with tournament brackets. Batters slotted in against rivals (at first, from the other league; now, based on slugger seeding) and a time clock replaces the allotted outs per round (the derby used 10 outs, 7 and 5 at various points).

Launchers now have three minutes (down from five) to sail baseballs into stands. They’re allowed to stop the clock once each round, can choose one 30-second bonus round and can obtain a second bonus stretch for smacking the ball beyond a pre-set distance. In each round, the slugger with the highest tally advances. The overall winner nets $1 million from MLB.

In theory, more hitter-friendly parks would lead to higher home run tallies, especially for winners. But that hasn’t necessarily been the case. Since the clock was introduced in 2015, the winning dinger totals were: 39 (Great American Ballpark, Cincinnati), 61 (Petco Park, San Diego), 47 (Marlins Park, Miami), 45 (Nationals Park, Washington, D.C.), 57 (Progressive Field, Cleveland), 74 (Coors Field, Denver) and 53 (Dodger Stadium, Los Angeles).

Coors as the outlier is the least surprising tally. With games played at mile-high altitude and an earned reputation as such a hitter-friendly park it borders on a competitive advantage, the Rockies’ home stadium all but guaranteed a staggering total. The 74 dingers Pete Alonso crushed were even more impressive than might be obvious, because the Mets first baseman won in the first derby with a clock reduced by two minutes, or 40% of the previous total. Even then, what about Great American? With its tight dimensions and hitter-friendly rep, that park clocked the lowest winning score, from Todd Frazier. Go figure. In the rest of the recent derbies, every other winner slugged between 45 and 61 home runs. And this modest variance, Tornado Ted believes, will continue at T-Mobile Park.

Could it lower the average? Maybe. An analysis of the Mariners offense last season, published by Lookout Landing this spring, provides some clues. The piece analyzed an “offensive backslide” that took place amid the best Seattle baseball season in decades, where the Mariners ended the longest playoff drought in U.S. professional sports.

The story uses Statcast data to build its argument, noting T-Mobile was the most difficult ballpark to hit in last season, same as the year before. This “cellar overall as an offensive environment” fell 9% below the league average of runs scored. Great American Ballpark ranked second, with 20% more runs recorded than in Seattle.

But, the story also found, a dearth of runs scored wasn’t exactly the same as little to no dingers smacked into the stands. Ever since team officials moved the outfield fences in left field and center field closer to home plate before the 2013 season, this has been consistently the case. The Mariners, pitcher-friendly park and all, consistently ranked just above the league average in home runs. Their offensive failures, relative to competitors, came in every other offensive category except that one. The piece also examined a three-year data sample, with more than 16,000 at-bats to study.

Perhaps, the author mused, this trend owed to roster construction. Maybe true launchers of baseballs were harder to coax to the Emerald City. Perhaps general manager Jerry Dipoto used the ballpark’s dimensions—and the statistics available to analyze them relative to other factors—to sign the right kind of batter; ideally, a slugger who bashes baseballs over fences, especially in home games. Otherwise, Dipoto needed players who could excel on defense and manufacture runs. He had to pay pitchers in order to stay competitive. This approach, born in part from necessity, helps the Mariners win. But it does not yield full-out (or fully rounded) offensive explosions.

T-Mobile Park, though, is a significant part of that equation. Of course it is. Colder and wetter weather conditions are a given in Seattle, especially in the spring, when the Mariners bats tend to go silent. According to the Lookout Landing story, the ball-flight distance at T-Mobile is 4.3 feet, on average, below the rest of the league. Across baseball, changes were designed to improve the flight path, from updated equipment (like the humidor-cooled balls), to ballpark designs and pitch clocks.

It’s fair, on one hand, to say T-Mobile, the antithesis of Coors, will present a derby conundrum sluggers must solve. But that’s not to say this Home Run Derby will lack the very reason the event exists. The ballpark can now embrace recent trends, in baseball and throughout sports, some of which portend doom far away from any games. Fact is, sluggers are bashing dingers at higher rates than ever before. This results from numerous factors—how training has evolved, for one; the pitch clock, for another … but none matter more than the most bleak. Which is, of course, global warming.

Let’s back up. Tornado Ted’s distinct path to Monday night may have started with The Columbus Day storm, but he would not be applying science to the flight paths of baseballs if not for the umpire gig he took in Lake Oswego at age 16. He called games for the 13-to-15 age group, then was promoted halfway through the season. In his first contest as an umpire for older teens, he threw out one of the coaches, a burly ex-football-tight end who rushed him in a huff. “The volcano went off,” he recalls. “And I said, you’ve got a minute to get off this field.”

Naturally, Tornado Ted was ready for eruptions. If he was the calm within the storm, as the cliché goes, the twist was that storms calmed him.

Buehner would later referee soccer matches, but umpiring baseball games became his other lifelong passion. Once he became an atmospheric scientist, he began melding two worlds that seemed to hold little in common on the surface. He discovered they were, in some ways, prominently intertwined. So much so, in fact, that years ago, during a rain delay, he got to talking with the other umpires. There were three of them—two, go figure, were meteorologists, calling baseball games as side hustles.

Tornado Ted saw hitters mention at-bats where they crushed a pitch but their line drives didn’t fly the way they should have. Or they’d point out home run rates rising after the summer starts. Both sentiments were true, in part because of atmospheric science. Warmer temperatures yielded higher humidity, which meant more moisture in the air and thinner air in general.

So Tornado Ted set out to relay information at that intersection, as one part of his much broader career. After retiring from the weather service in 2018, he began teaching webinars, filming spots for local TV and radio stations (their tenor only sometimes tied to sports) and teaching national disaster preparedness at a training center, all while conducting all manner of interviews like this one. The packed schedule keeps Buehner engaged and allows him to pass along information to a small set of humans who actually understand.

Tornado Ted is an altruist, giving media tours to journalists in his “spare” time, a practice he started during the weather service days. For his first presentation, back in 1995, Buehner visited The Seattle Times before the Fourth of July and schooled reporters on fire season and preventive measures locals could undertake. He talked to staffs at television stations, interns in all storytelling mediums, interested businesses … anyone, basically, who asked. He broke down floods, tsunamis, hurricanes, wildfires, extreme heat and, more recently, water safety, to prevent summer drownings at state parks where the air is hot but the water cold.

All audiences want to know about higher temperatures, about global warming and how it will impact their lives. Buehner tells them that a typical Seattle summer now lasts three weeks longer than one did in the 1950s, a fact he cites from a study that examined the city temperatures through 2010. The next decade was the warmest ever, bolstering the findings. Temperatures last October were nine degrees higher than their average a year earlier.

The intersection of baseball and atmospheric science still interests him. Tornado Ted hosts those seminars at T-Mobile Park, formerly known as Safeco Field. He does at least one in most years, explaining and debunking, eliciting fear in one sense (all the warming) and reducing it in another (the alleged dearth of home runs at Seattle’s ballpark). Often, he speaks to children or teenagers on Weather Education Day, explaining what can, empirically and easily, be explained.

Buehner often begins these sessions with a digression on air density. If it’s 95 degrees outside, for instance, the air is 12% less dense than when the temperature drops near freezing. This also means the air is thinner when it’s hot out. The same stroke—same pitch speed, swing, smack—will carry the ball 408 feet in 95-degree weather; at 75 degrees, 400 feet; at 55 degrees, 392 feet; and at 45 degrees, only 384 feet. Those margins might seem small. But they are significant, proof that batted balls carry further in warmer weather, albeit influenced by other factors (bat speed at point of contact, exit angle, time of day).

The amount of moisture in the air also matters, because it adds to air mass. The Mariners play home games inside a stadium built in a city with colder temps and heavy, dense spring air. At least in the season’s early months, there should be fewer dingers launched at T-Mobile Park.

Even then, the Mariners opened their new ballpark in July of 1999. In the 24 seasons since, including that one, Seattle finished in the top 10 in home runs 10 different times, while sliding into the top five in five of those years. Tornado Ted points to some of those M’s teams—those with elite batting lineups, like in the early 2000s—as proof sluggers can smack baseballs in Seattle. And wallop, they did, even before MLB changed its baseballs and incorporated humidifiers.

When Tornado Ted adds up all the factors and season statistics, he begins to debunk some of the prevalent notions about T-Mobile. Like most descriptions of Seattle (Gloomy! Rainy! Coffee addicts! Hippies!) these are lazy, grounded in truths and widespread stereotypes. In general, he says, “I would say [Seattle’s alleged run problem] is generally overstated.”

This—and much more—relates to the derby. Temperatures in Seattle have risen in recent weeks, as in most, if not all, years. Nothing like the brutal heatwave in Texas, but temperatures climbed into the 80s and 90s. The forecast for Monday’s Home Run Derby predicts a high of 71 degrees, partly cloudy weather and 6% moisture in the air—the highest moisture level in the past week. If it rains, officials can always close the retractable roof.

For this, fans who dig the long ball can thank a perpetually warming planet. Tornado Ted first began to notice the ever-more-alarming trend in the late 1970s. As decades of news accounts attest, global warming has only worsened since. Buehner runs through a few of myriad examples: the highest measures of carbon dioxide concentration ever, in Hawaii, for several consecutive years; higher acceleration of warming levels annually; condominiums in Florida threatened by rising tides; melting glaciers, melting ice caps; not to mention, a surge in number of storms and their intensity. Of course the volume of home runs, for any team in any park, is tied to the warming and its impact. There’s even empirical proof.

In March, four authors submitted a study to the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. The idea for it started with one, Christopher Callahan, a Dartmouth professor and lifelong Cubs fan. Callahan knew physicists and baseball nerds had long floated what seemed like an obvious notion: warmer and less dense air meant more home runs in his favorite sport. But no one had ever examined that sentiment with large-scale data—until the authors did.

They pooled points from 1980 onward, from roughly 100,000 MLB games and roughly 240,000 at-bats. Then they isolated “human-caused warming with climate models” and ran a regression analysis. The results—that human impact on rising temperatures meant in excess of 500 additional home runs since 2010—proved striking and portended to only increase in future seasons.

Callahan describes the main takeaway as straightforward, mainly because the physics of reduced air density are just as linear. What most surprised him, though, was the variance between ballparks. In some—often stadiums without roofs, for instance; or places like his beloved Wrigley Field, where they play more day games, when it’s hottest outside—homers flew out with dizzying regularity. “Those temperatures,” he says, “can exert a real influence.” In other parks—like dome stadiums, or places with few day games—the influence was smaller; the gulf, wider than expected.

T-Mobile fits within those findings. Because of its roof, the spring weather in Seattle and some day games but not an overabundance, global warming appears to have impacted its home run tallies far less than other factors. Like the club moving in some outfield fences. Or turning toward humidors faster than other franchises across MLB. But that’s not to say global warming had no impact on sluggers in Seattle.

It did, which is good news for anyone who loves the derby. Since publishing, Callahan and his co-authors heard from several folks in baseball. Like Dave Martinez, the Nationals manager, who believed the study confirmed what he was seeing on fields all over the country. As the weather warmed in any season, baseballs leapt off bats and cruised like missiles. And, while that happened to some degree in every MLB season ever played, it seemed to be happening with increasing regularity each year now. And, since this home run derby will be held in what’s typically the hottest portion of a Seattle summer, there’s little reason to believe the air will dampen the tally in any significant way, according to Callahan and Tornado Ted.

This, Buehner worries, might lead to an unintended consequence. Like many Seattleites, he fears viewers will glimpse the Seattle that locals love to hide from wider audiences. They prefer to keep the city’s secret: that it doesn’t rain much here, or all that hard. They don’t mention that Miami— beautiful, sun-kissed, all-year-is-beach-season Miami—is wetter, on average, annually. The more people who find this out, the more Seattle’s population seems to swell, especially as temperatures everywhere warm.

“The ball is going to carry,” he says, firmly, further erasing concerns that this iteration will be the worst in derby history. Homer-less in Seattle, this is not.