As Home Field Advantage Dominates NFL Playoffs, Why Is MLB Trending the Other Way?

Another NFL playoff weekend and another strong showing by home teams: 5–1 in the wild-card round, followed by 3–1 in the divisional round playoff and 1–1 in the conference championship games, for a record of 9–3, the same mark as last year. That’s an 18–6 advantage (.750) for home teams over the past two years, well past the previous .670 mark since 1990.

Meanwhile, the impact of baseball’s home field advantage on how championships are decided is trending in the opposite direction. Forget what you learned growing up about how important it is for baseball teams to play at home in the postseason. Here is the evidence that the home field advantage in baseball is at a five-decade low:

- Home teams in the regular season last year posted a .521 winning percentage, the worst in any full season since 1971 (.519).

- Home teams last year in the postseason were 15–26 (.366), the worst in any postseason since 1970 (4–7, .364).

- Home field advantage no longer exists in a sudden death playoff game (both teams facing elimination). From 2018 to ’23 (not including the COVID-19-affected ’20), home teams are 6–10 in such ultimate showdown games.

- In that same five-postseason span, more series have been won on the road (27) than at home (22).

- In the 2019 World Series, home teams were 0–7, an unprecedented failure.

- The 2023 Texas Rangers were 11–0 on the road in the postseason, an unprecedented success.

- The home regular-season winning percentage has declined for the past three years.

- Home regular-season winning percentage in the 2020s is .534, the lowest among the 11 decades of the Live Ball era and down from the high of .553 in the 1930s.

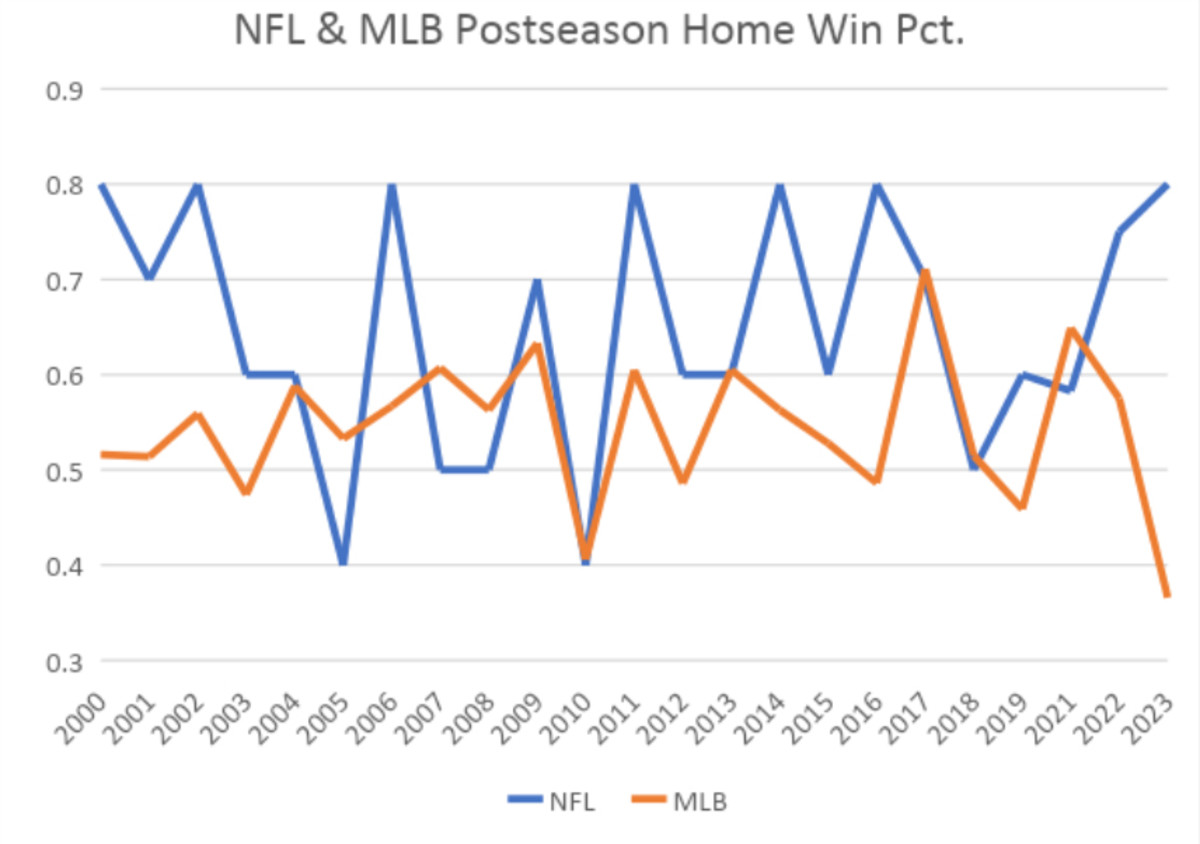

Here are the trend lines for NFL and MLB home teams in postseasons since 2000 (with ’20 excluded):

Take note of the divergence of the trend lines at the far right side of the chart. Over the past four full seasons, it has become much harder for home teams to win postseason baseball games and slightly easier for home teams to win football playoff games:

MLB W-L, Pct. | NFL W-L, Pct. | |

|---|---|---|

Past Four Full Seasons | 79–76 (.510) | 31–15 (.674) |

Previous Four Full Seasons | 80–62 (.563) | 26–14 (.650) |

O.K., so why is this happening? In the NFL, as presnap reads become more important, the home crowd’s impact on the game becomes more pronounced. You saw an example of that Saturday with a half-dozen presnap penalties for the Houston Texans on the road against the Baltimore Ravens. Baltimore coach John Harbaugh credited his fans for influencing the false start penalties, calling the noise “deafening.”

In MLB, noise level has far less impact on game outcome. So why over the past 155 postseason games (2020 excluded) is home field advantage in postseason baseball hardly any better than a flip of a coin? Here are some theories as to why home field advantage is shrinking in baseball, both in the regular season and especially in the postseason:

The homogenization of playing fields.

Detroit Tigers manager Sparky Anderson used to keep the infield grass absurdly high at Tiger Stadium when his staff was loaded with ground ball pitchers. Shea Stadium and Fenway Park had notoriously uneven infields. The pitching-rich Los Angeles Dodgers built their mound higher at Dodger Stadium. Visiting bullpen mounds in many ballparks were kept in disrepair. Visiting clubhouses were shockingly small and sparse. The Rangers liked to crank the air conditioning in the visiting clubhouse to ridiculously cold levels, the more the heat would affect opponents at game time. One team kept two ball bags at home: one for offense and another, which had spent time in a refrigerator, for defense. At least one pitcher gave a hefty tip to the home clubbie if he put extra pregame rubbing mud on the baseballs to make them darker.

Few such shenanigans still exist. Now every playing surface is perfectly level. Grass and mounds, including those in the bullpen, are kept at standard heights. Infields, including the base paths, are perfectly flat. (No more turtlebacked fields to accommodate water runoff.) They are regroomed three times a game. Bad hops are rare. Even artificial surfaces, which used to vary in terms of bounce and hardness, play very similarly to grass fields. Baseballs are stored in climate-controlled humidors with an exacting chain of custody. Visiting clubhouses are as posh as five-star hotels.

The intimidation factor is much lower.

One of the loudest venues in MLB these days is Citizens Bank Park in Philadelphia. And yet a young Arizona Diamondbacks team won two elimination games there while playing errorless ball, allowing just three runs and striking out 21 batters. Baseball has grown so big on the amateur and minor league levels that young MLB players already have vast experience playing in pressurized environments with attendant media.

The adage about young players not being ready to play in stadiums with a third deck is outdated. Teams trust young players far more to handle the MLB environment than they did a generation ago. Last season, a record 24 players age 23 and younger hit at least 10 home runs.

Travel and recovery are improved.

Most teams have “sleep coaches” who will plan for the optimal time for air travel between cities. High-performance coaches and nutritionists monitor energy levels of players, to say nothing of hyperbaric chambers, cryotherapy, hot and cold tubs, and assorted other advances in fitness maintenance. Four decades ago, teams flew commercial, and players slept two to a room on the road.

Umpiring has improved.

According to the 2011 book Scorecasting, umpires gave more favorable calls to the home team in critical situations. Pitch-tracking technology was in its infancy then. Not every ballpark had the QuesTec tracking system. The authors found umpires’ calls went the home team’s way only in ballparks without QuesTec.

Baseball now has tracking technology everywhere, and it is the gold standard of how MLB grades its umpires. The new generation of umpires has been developed through the minors with tracking technology that doesn’t care where the game is played or the leverage of the situation. The umpires call a “purer” strike zone not nearly as influenced by the game environment.

A more even distribution of talent.

I made this point recently why the Dodgers, as loaded as they may be, are no lock to win the World Series: Over the past 13 postseasons following full seasons, the team that enters the playoffs with the fewest wins has virtually the same chance of going to the World Series as the team with the most wins. The “lowest seed,” if you will, is 65–52 (.556) with four pennants, and the “highest seed” is 67–51 (.568) with five pennants.

Just about any team that gets into the playoffs can win a pennant. That kind of equilibrium rarely existed in baseball or other sports before.

The 2023 Rangers stand as the perfect piece of anecdotal evidence to what is happening. They won only 90 games in the regular season. They had to play a wild-card round at Tampa Bay, which owned the best home record in the league—and swept two games. They advanced to play Baltimore, which had the best record in the league—and swept them. Facing ALCS elimination, they won Games 6 and 7 at Houston by a combined score of 20–6. They took out Arizona in the World Series by winning three straight in Phoenix.

At age 20, Texas outfielder Evan Carter became a middle-of-the order force who slashed .300/.417/.500 in the postseason. Fellow Rangers rookie Josh Jung, 25, slashed .308/.329/.538.

Time and time again, with players short on postseason experience, the Rangers underscored what’s been happening for years: Home isn’t as sweet in baseball as it used to be.