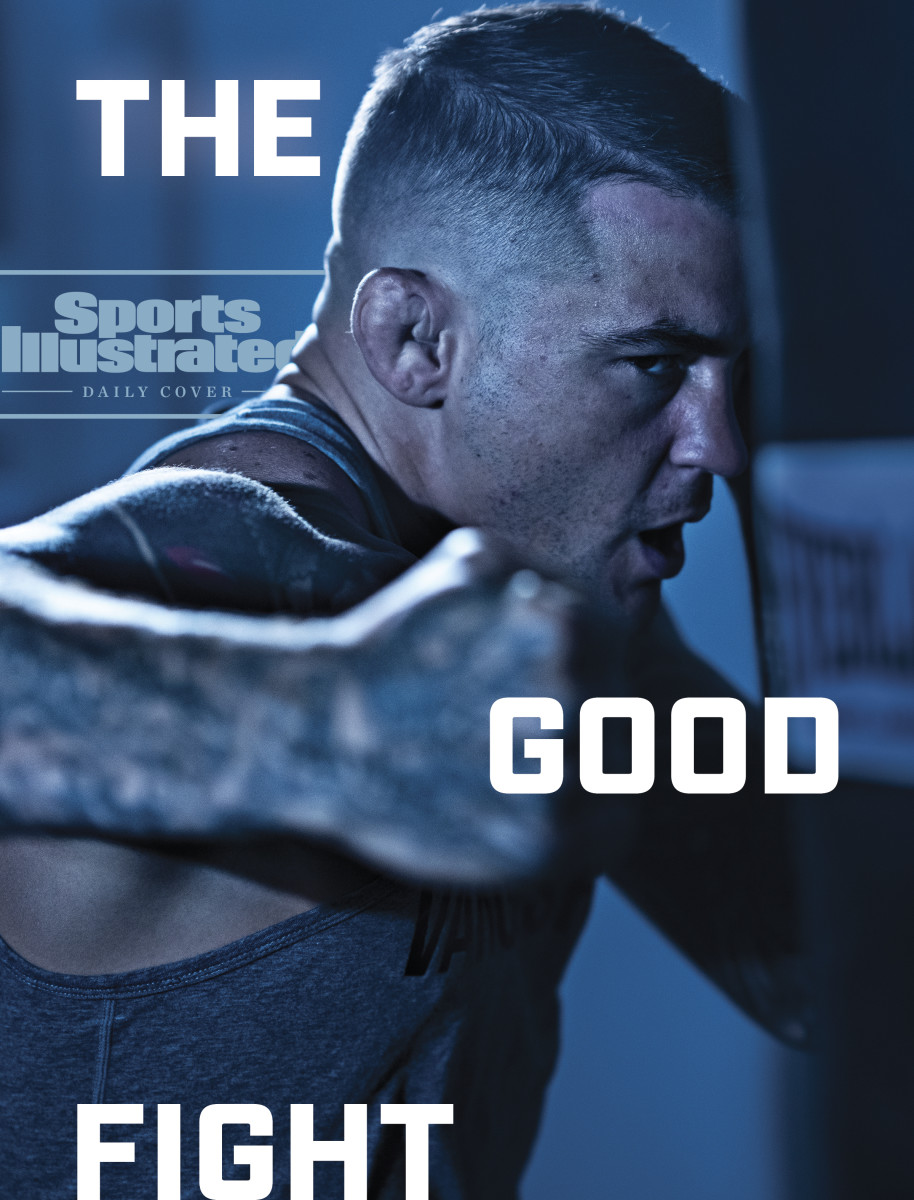

Bright Like a Diamond

The bangover, they call it in mixed martial arts. It's that interval after a fight when combatants try to regain equilibrium. In some cases the quest is physical, from the toll of violence dispensed to their bodies, but in all cases it's emotional, easing back into society after funneling and tunneling all that energy and intensity into the singular mission of beating an opponent.

After defeating Conor McGregor in one of the most well-promoted fights in UFC history, lightweight Dustin Poirier appeared unscathed. While McGregor’s leg was Theismann’ed, forcing him to leave the Octagon in a stretcher, Poirier was back at his Las Vegas Airbnb a few hours later, smiling as he grilled pizzas in the backyard.

But two weeks later Poirier, 32, was still experiencing the bangover. “It’s like divers who’ve been underwater and then come up for air,” he says on this July night, opening a door to his garage in Lafayette, La., where 1,000 stuffed backpacks await distribution to children in need. “I know all athletes must go through this. But it’s probably pretty extreme in this sport, wouldn’t you say?”

Poirier and I carefully consider this question. Sure, Giannis Antetokounmpo had been focused on winning the NBA title, but he didn’t put himself through a 10-week training camp for the express purpose of beating the Suns. He didn’t have to deal with an opponent threatening to kill him—and bed his partner. He didn’t have to go through the torture of cutting 15% of his body weight immediately before Game 1. So, yeah, we conclude, the release of the pressure valve is different for MMA fighters than it is for other athletes.

And the bangover is all the more intimidating when you strive—as Poirier insistently does—for conventional living. He has no interest in celebrity trappings or velvet roping or the “noise” (his word) of social media. When he’s not fighting, he just wants to be home. Back to his wife, Jolie. Back to his daughter, 5-year-old Parker Noelle, who refers to her dad’s profession as “punch-punch.” Back to the four-bedroom on a quiet cul-de-sac.

In fact, the morning after dismantling McGregor, Poirier boarded a plane (commercial, changing in Atlanta) to return to Lafayette, a refinery town two hours west of New Orleans. One day you’re headlining press conferences and featured on commercials throughout the NBA playoffs. The next day you’re at your quiet suburban home, kibitzing with the ENT doctor next door about lawn care. You’re taking packages to the post office, stopping by your mom’s house and helping your daughter unwrap a miniature pony made of chocolate.

Beating the voluble McGregor in January, then doing it again in July? That’s surely when Diamond Dustin Poirier pierced the mainstream. But to MMA tribalists he’s been a known quantity since he was a teenager. That was when a New York City film crew came to his hometown to shoot the cult documentary Fightville.

The 2011 film focused largely on a haunted young fighter named Albert Stainback. But a handsome, buzz-cut, baby-faced comer at the same gritty gym stole most of the scenes. In one, young Dustin unfurls his Cajun accent to explain why he does what he does. “Fighting,” he says without affect, “has opened a path to redemption for me.”

Growing up in a rough section of Lafayette, Poirier attended Northside High, where UFC Hall of Famer Daniel Cormier had been a student a decade before. But while Cormier graduated and went to Oklahoma State, where he became an All-America wrestler, Poirier dropped out as a freshman and spent his teens in juvenile detention and low-wage jobs. His answer to the inevitable question that gets asked of Louisianans of a certain age: Where were you when Katrina blew through, in 2005? He was working his shift at McDonald’s.

Poirier was floundering. And at the same time, he was in love—both with a woman and an activity. Jolie LeBlanc, a girlfriend since middle school who saw something in Poirier, won him over. So did boxing, and then mixed martial arts. Sure, the sports were ways to offload all that anger and offset his failures. But the balletic mayhem was also a strategic challenge that obsessed him.

“Everyone is like, ‘There are so many different ways to win,’” Poirier says. “Sure, but that also means there are so many ways to lose. Elbows, knees, chokes. . . . It wasn’t just about learning all the skills and moves; it was learning how to avoid having them done to you. It’s the theater of the unknown, man.”

Without the means to buy a car, Poirier asked LeBlanc to drive him to his first fight, at a rodeo arena in Texarkana on an undercard in 2009. He won, and his climb began. Poirier quickly appreciated that every bout brought with it a fresh adventure. Sometimes he won easily, sometimes in a struggle. Sometimes on the ground, choking his opponent, sometimes standing up. Sometimes against fighters who led mostly nonviolent lives outside the ring, sometimes against rougher sorts. (Shortly after losing to Poirier, one opponent shot a man dead.)

Fighting became a destiny Poirier couldn’t help but accept. And it transformed his life. The sport demanded so much time, discipline and focus that it crowded out his lesser angels. The knowledge that he was getting better instilled confidence; the modest payouts and the beatings at the gym bred humility. “Adversity,” Poirier says, “introduces a man to himself.”

On New Year’s Day 2011, Poirier was 21 and had recently married Jolie. The UFC had summoned him for his first fight—MMA’s equivalent of the call-up to the big leagues—and he won by unanimous decision. Since then his career has taken on a distinct rhythm. Poirier would gather victories and buzz and be just on the precipice of a breakthrough—then lose. Nothing embarrassing or physically damaging, but a backslide. Then he’d start winning again.

In the fall of 2014, at UFC 178, Poirier was on the ascent again when he faced McGregor, an Irish fighter known for his elite trash talk and suspect ground game. But barely two minutes in, McGregor starched Poirier with a right hand, rained down hammer fists and won by knockout.

If that fight vaulted McGregor to real stardom, it didn’t exactly throw a crowbar into the wheels of Poirier’s career. He went back to the gym and won four straight bouts. His rise traced the same arc as that of mixed martial arts—and the UFC—itself.

When Poirier started his career the sport was illegal in dozens of states—“human cockfighting,” then Senator John McCain (R., Ariz.) memorably called it in 1996. But with blazing speed, it moved from the margins to, if not the mainstream, at least something fit for airtime on ESPN. Folks around Lafayette who once asked, “Is your sport real or fake?” were suddenly asking him about the finer points of grappling or whether he would move up in weight class.

As the sport evolved, so did the training. Though unwilling to give up his base in Lafayette, Poirier got an small apartment in Coconut Creek, Fla., and started training at American Top Team, a breeding ground for alphas 20 minutes north of Fort Lauderdale. He also began working with a mental coach, who told Poirier to draw two concentric circles: an inner one that lists all the things he can control (like diet, work ethic, commitment) and an outer one that lists all that he can’t (such as his opponent). “If I just check the boxes that I have available to control, things usually work out,” Poirier says.

From 2017 to ’20 he won six fights against the best in the lightweight division, a Star Wars cantina of personalities and styles that included Anthony Pettis, Max Holloway and Justin Gaethje. Poirier’s only loss in that period came at the hands—via rear naked choke—of Khabib Nurmagomedov, who’s regarded as the MMA GOAT.

In January, Poirier faced McGregor in a fight sold, tepidly, as a rematch of their 2014 bout. Poirier dominated and won by knockout in the second round. Before the re-rematch on July 10, McGregor was McGregoring—“I’m coming in with vicious intent here. Mortar shots. I’m looking to take this man out cold”—and joking about DM’ing Jolie.

When Poirier and McGregor finally stopped talking and started fighting, substance demolished style. Late in Round 1—which Poirier won—McGregor snapped his left shin on Poirier’s thigh. He sat on the floor of the cage, his foot contorted at a grotesque angle. From the ground, McGregor continued: “This is not over. If I have to take this outside with him, I’ll go outside. I don’t give a bollocks.” It had the ring of hoodwinked Mortimer Duke at the end of Trading Places, demanding that the commodities exchange remain open.

Poirier, too, wishes the fight could have lasted longer. “I would have loved to keep bringing him into deep water,” he says, pounding a fist on the marble countertop in his kitchen. “If his leg wouldn’t have broke, his heart would have broke. His mind would have broke. I promise you, I would have broke something else. . . . I wish we could have got a little bit more bloody.”

Flattening Conor McGregor comes with considerable perks. Most obviously there’s the financial: Poirier’s UFC 264 pay, as reported to the Nevada athletic commission, was $5.1 million—a base of $1.5 million, $2 for each of the 1.8 million pay-per-view buys, plus a small sponsorship stipend. While it’s an open secret that the UFC sometimes finds off-the-books ways to sweeten compensation, its payouts are still scandalously low compared with those of sports with salary caps. Then again, if you rose through the ranks not even sure your sport would remain legal, it’s a lot less likely that you’d complain too much—and Poirier doesn’t—about earning seven figures for five minutes of in-Octagon work.

Fallout from July’s victory: There are business opportunities, ranging from the intriguing to the ridiculous. One minute he is explaining that a production company is pitching networks a Poirier-hosted travel show. A moment later he shows a gift from Jake Paul. It’s a necklace of white gold with a pendant depicting McGregor knocked on his ass.

Shortly after, an offer came from the Middle East: A fight fan offered to buy the necklace for $100,000. Poirier had a better idea: He would auction it off for The Good Fight Foundation, which Jolie runs. While Poirier has made pennies on the dollar compared with McGregor—whose whiskey brand alone might be worth $1 billion—his list of charitable deeds is so long it could be serialized.

Poirier has auctioned his gloves and fight kits to subsidize the family of a Louisiana police officer shot in the line of duty. The foundation has donated thousands of meals during COVID-19 to the major hospitals in and around Lafayette. This summer he has taken an interest in helping to provide clean drinking water to Ugandans. (After UFC 257, McGregor pledged to donate $500,000 to the charity; one of the few questions Poirier ducks is about whether the payment was ever received.) Not for nothing did the UFC confer on Poirier the inaugural Forrest Griffin Community Award last year.

While fighters raising millions for charity is a sign of the UFC’s evolution, so is the cozy lifestyle Poirier leads. Barely a decade ago he was on food stamps; now he is almost done with Parker Noelle’s college fund. After he and Jolie married, they pooled their money and drove to the Florida panhandle for their honeymoon. Now Poirier rents out practically half the panhandle for an annual vacation for his extended family.

Having beaten McGregor, Poirier only has one more rival in his way: Charles Oliveira of Brazil, the reigning lightweight champion. On December 11, at UFC 269, the two will fight for the division's belt.

Who knows how many fights he last left? Certainly not Poirier. “I don’t wanna be the guy who’s squeezing,” he says. “I’ve seen it time and again. They’re trying to squeeze one more paycheck, one more fight. I don’t wanna be that guy. . . . You know what? I can walk away and be happy, and my family is going to be O.K.” He doesn’t want to be stuck in an eternal bangover.

Then, like a fighter switching to southpaw style, Poirier resets. He still lives for fighting, those minutes in the cage when there are no pretenses or hype. “Under those lights, yesterday doesn’t matter. Tomorrow doesn’t matter. All you have is right now,” he says.

But he’s also come to fully appreciate the absurdity of his livelihood. A UFC fight fan, Poirier, more often than not, buys the pay-per-view cards and spends plenty of Saturdays watching two people clamber into a cage and beat the bejesus out of each other.

Forgetting for a moment that he was watching colleagues one Saturday, he said aloud what plenty of people still think: “These f---ing guys are crazy. These guys are nuts. Oh, my god, these guys are insane.”

• After an Oscar ... a Butt-Kicking?

• UFC's Welterweight Champ Is Built for the Pressure

• He Nearly Died on 'Drive to Survive.' Now He's Faster Than Ever.