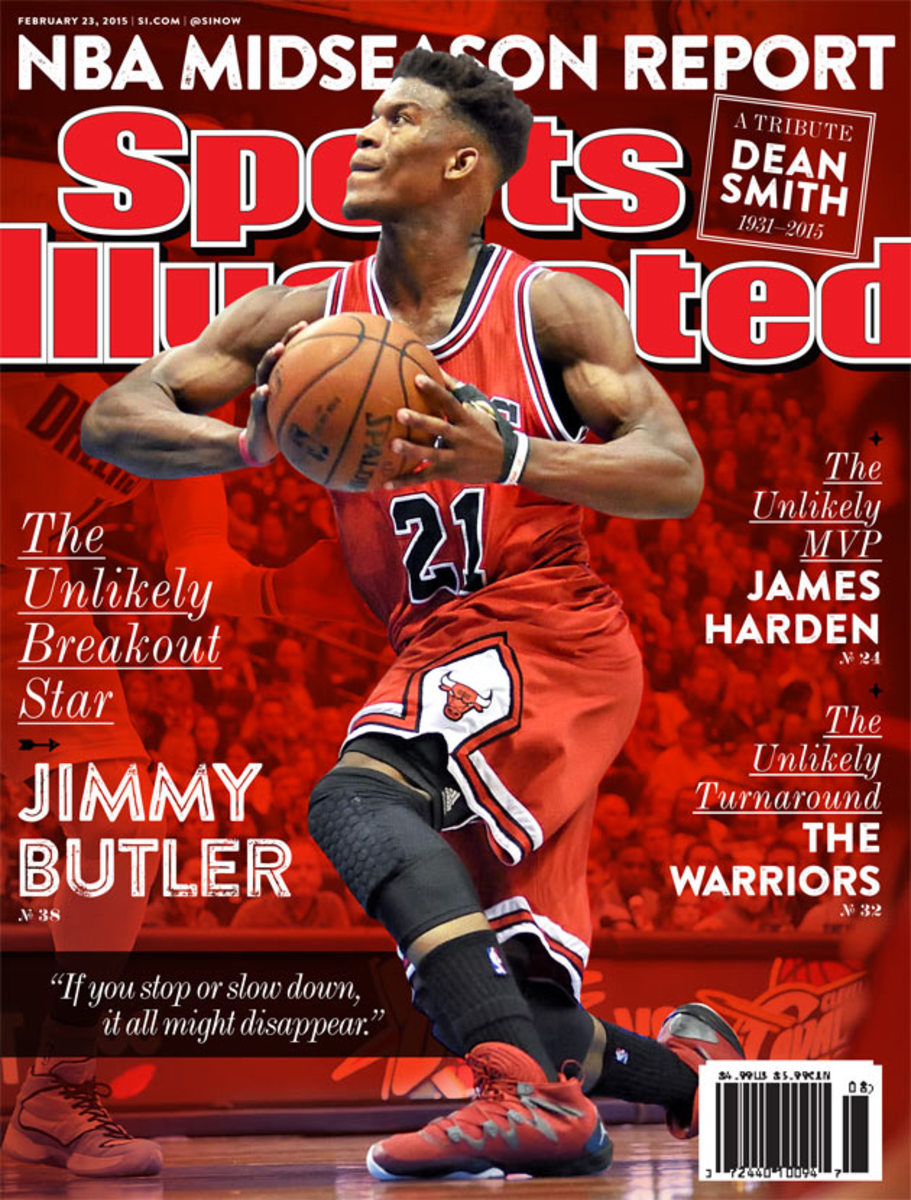

Jimmy Butler: Running The Gauntlet

Editor's note: This story appears in the Feb. 23 edition of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

Jimmy Butler's signature move isn't a single action at all, but a flurry. His constant movement is at once exhilarating and exhausting—poaching in passing lanes, bulldozing through screens, blazing on the break, storming the paint, pounding in the post. The numbers confirm the impression that the Bulls' lithe, 6'7" swingman is everywhere at once: Butler leads the NBA in minutes played and, according to motion tracking cameras, distance covered on the court. During a December win over the Knicks he had an offensive rebound, a steal and two assists in 44 seconds. In January he scored nine straight fourth-quarter points in 67 seconds to help force overtime against the Lakers.

Butler, 25, first arrived on the NBA scene as a designated shadow, following the opposition's star wings wherever they went. But this year he has taken over the spotlight, averaging 20.4 points, 5.8 rebounds and 3.2 assists, all career highs, to become the favorite for Most Improved Player. NBA fans recognized Butler's progress on nearly a half-million All-Star ballots—votes of confidence, so to speak—ranking the former defensive specialist among the 25 most popular players in the league.

He has risen from a homeless, withdrawn teenager in Tomball, Texas, to a confident Eastern Conference All-Star, and another chapter of his remarkable story is coming in July, when he is likely to sign a max contract.

Michelle Lambert, the mother of four biological children who welcomed a 16-year-old Butler into her home, watches every Chicago game. "Mommy," as Butler calls her, sees the lessons that he absorbed as a teen play out in his full-bore charges from baseline to baseline. "Going fast is instilled in Jimmy," Lambert says. "If you're moving and producing, you stay in the plans. If you stop or slow down for a second, it all might disappear."

• NBA MIDSEASON: Harden: Unlikely MVP | Warriors: Unlikely contenders

About 40 miles northwest of Houston, Tomball is a suburban town of 11,124, or just more than half of the United Center's capacity. Butler is Texas proud. He prefers cowboy boots to dress shoes, and his agent, Happy Walters, says Butler would "much rather hang out with Garth Brooks than Lil Wayne." Butler can be seen on Instagram, a red bandana around his neck, riding a horse. He name-checks his hometown in interviews and more than once has challenged reporters to find it on a map. "Tomball isn't as country as people make you think," Butler says. "We have like three Walmarts. We have a lot of stoplights. It's cool."

Caucasians outnumber African-Americans by more than 15 to 1 in Tomball, and the town has had episodes of racial tension. In 2005, while Butler was a sophomore at Tomball High, the White Camelia Knights of the Ku Klux Klan held an event at the town's community center. In '13 an African-American student at Tomball Junior High received a KKK-themed birthday party invitation from two classmates. Butler happily recalls a childhood spent trying to be the fastest—outracing kids on the football field, rushing to turn in his multiplication tests first, scarfing down dinner before everyone else at the table—and describes Tomball as "mellow" and "family-oriented." Yet those words could hardly be less applicable to his own upbringing.

By age 13, Butler found himself without a permanent residence. His mother, Londa, kicked him out of her home, saying, as Butler told ESPN.com, that she "didn't like the look of him." Jordan Leslie, Michelle Lambert's son and Butler's close friend, refers to a precipitating "incident" between mother and son but refuses to go further, calling it "Jimmy's business." Londa declines to comment on the subject, and Butler tenses up when it is broached. He again puts up a wall when asked about his early relationship with his father, a truck driver also named Jimmy.

When none of his extended family stepped in, Butler moved in with his friend Jermaine Thomas. "We were always together as kids," Butler says. "I consider him to be my brother." The pair first lived without much direct parental supervision in a two-bedroom house rented by Thomas's father, also a truck driver and often on the road, and then took to sleeping over at friends' houses for days at a time. "There were times we needed to make 10 bucks last all week for lunch money for both of us," Thomas says. "We would eat a bag of chips and Gatorade every day."

It would take two years of hand-to-mouth living before Butler received his first vote of confidence. Before his senior year Butler crossed paths with Leslie, a freshman, at a summer basketball tournament. The two teens quickly discovered a shared love of sports, and Leslie's own childhood struggles helped him connect to Butler. Leslie's father, who was African-American, had been struck and killed by a car.

• MORE NBA: Rose's latest injury leaves Bulls mentally drained

The summer before Butler's senior year Lambert welcomed him and Thomas into her four-bedroom home. An engineer tech at Hilcorp Energy, she remembers Butler as "deathly shy" and "very quiet," conditioned to keep a low profile so that he wouldn't be kicked out of wherever he crashed. She harbored no hoop dreams for Butler's future; the blonde "Mama Bear" simply couldn't turn him away once Leslie told her that Butler and Thomas had nowhere else to go, even if that meant cramped quarters and a strained pocketbook.

When Butler moved in, his only possessions were a collection of well-worn T-shirts and basketball shorts. He slept on the couch or on the floor out of habit and convenience to the family. He would race from Leslie's bedroom down the stairs and out the front door to avoid any possibility of conflict, and he completed his chores without complaint. In Lambert's eyes Butler was a "damaged little bird" who struggled with trust issues, who recoiled from something as simple as a hug. His pain was so evident that Lambert made it a point never to pry into his past.

On the court, Butler admits, he compensated for feelings of inadequacy with an "ego problem." Envisioning himself as the next Tracy McGrady, the Rockets' star he idolized, Butler would brag to teammates that he could score 40 points on Derrick Rose, if the top player in the 2007 high school class would only dare come to Texas. But despite earning All-District honors as a senior, Butler failed to make real noise in Houston's AAU scene and received no Division I offers. "I was never good enough," he says, shaking his head. "It was always me against the world. I thought like that for so long."

Butler was no longer consumed by the horrifying question, Will the lunch money last? But he still faced a daunting predicament familiar to high school graduates: Now what?

Seeing no better option, Butler enrolled at nearby Tyler Junior College, hoping it would serve as a springboard to D-I. He was spotted by Marquette assistant Buzz Williams, on assignment to scout another Tyler player. Williams took the liberty of approaching Butler after the game in a meeting that called to mind an Old West stare-down between a couple of hard-chargers from small-town Texas. "He told me that I f------ sucked," Butler recalls, laughing. "That I was just flashy. That all I do is worry about myself and that he would show my ass if I was playing for him."

Warriors: From one-dimensional and one-and-done to NBA title favorites

Though Butler was initially put off, his delicate ego wounded, the pitch worked. When Williams became the Marquette coach in April 2008, Butler was his first recruit, committing to move 1,100 miles to Milwaukee despite having previously left Texas on only two brief occasions. The scholarship offer was Butler's second vote of confidence, but Lambert believes it was Williams's candor that ultimately made him the first real male authority figure in Butler's life. "I was just telling him the truth," says Williams, now the coach at Virginia Tech. "He knew he had a lot of work to do."

The fall semester had barely started before Lambert was flooded with phone calls. "Mommy, I want to come home; I made a mistake," Butler would plead, only to hear Lambert tell him to "suck it up." Having left his small pond behind, Butler was now simply a big fish out of water. He arrived shortly before classes started, bringing only his familiar T-shirts and shorts. Soon he would have to raid his teammates' closets for clothes: He remembers being so naive that he hadn't considered the weather in Wisconsin might differ from what he was used to in Texas.

The basketball transition was just as hard: The Golden Eagles' roster included future pros Wesley Matthews, Lazar Hayward and Jerel McNeal. "I got humbled really quick," Butler says. Looming over everything was Williams, who was trying to make a name for himself and was more than able, Butler says, "to rip your heart out in a heartbeat." He laughs now about all the times he got chewed out. "Chewing is the right word," Butler says. "[Williams] dips, he chews tobacco. He's spitting in your face, he's yelling, it's brown, it's really bad. But he doesn't care."

"Going fast is instilled in Jimmy," Lambert says. "If you're moving and producing, you stay in the plans. If you stop or slow down, it all might disappear."

Butler responded by adopting an entrepreneurial approach. He put his T-Mac dreams on hold and committed all out to offensive rebounding and passing, creating extra scoring chances for his more experienced teammates. "I had to figure out my way to play," he says. "I could do no wrong if I gave up the ball to them. And then I would get playing time."

By his junior year Butler had persuaded Williams to give him 34 minutes a night. Marquette's roster was undersized, and Butler's length, motor and ability to play multiple positions were all pluses. "It was incredibly hard to take him off the floor," Williams says. "He wasn't great at anything, he just wasn't bad at anything." Butler's dedication and intelligence set him apart. "Jimmy never dropped a class, he never missed a weight session, he was never late to anything," Williams says. "He was doing exactly what was asked of him. Jimmy is very smart academically, and he's very smart off the floor because of all the things he's been through. He has an uncanny ability to connect the dots."

The next round of motivation would come from bitter disappointment. Marquette entered the first round of the 2010 NCAA tournament as the favorite against Washington, but Quincy Pondexter drove past Butler for a game-winning runner in the closing seconds. Butler says that was the turning point of his college career. "I taped the picture of that play to my door so that every day when I woke up, I could see Pondexter sending my ass home, scoring on my ass like I was nothing," he says, still disgusted five years later. "I told [Williams] from that day forward, I was going to be a great defender."

"He realized that lives change on a single possession," Williams says. "He has an insatiable desire to get better. His drive is pure. He's willing to sacrifice."

As a senior Butler wasn't named to any of the All-Big East teams, but he led Marquette to the Sweet 16 and graduated with a communications degree. Recently Butler surprised Williams by showing up at his home unannounced on the coach's birthday. He spent the entire day with Williams's family, going to a pizza parlor for dinner and tucking Williams's kids into bed. "Our relationship was never built on basketball," Williams says. "That's not what his heart needed."

Butler next applied his relentless approach to the 2011 predraft process. He took home MVP honors at the Portsmouth Invitational Tournament, and his energy caught the eye of Walters, whose Relativity Sports firm was just getting serious about basketball. Walters hounded NBA executives to invite his new client in for workouts and made sure Butler had a spot at the league's official combine. After years of scrounging for respect, Butler began to feel validated. Doc Rivers, a Marquette star in the early 1980s who was then the Celtics' coach, couldn't stop praising Butler to his former assistant, Bulls coach Tom Thibodeau. Chicago delivered Butler's third vote of confidence, selecting him with the final pick in the first round.

Thibodeau quickly concluded that the Bulls had landed a gem. Butler was a tireless, physical, selfless, defensive-minded wing, a strong fit for Thibodeau's suffocating style and a perfect understudy for All-Star forward Luol Deng. "If they don't bite as puppies, they usually don't bite," Thibodeau says. "Jimmy was biting right from the start."

The national NBA audience got its first real introduction to Butler during the 2013 playoffs. Butler played all 48 minutes in five of Chicago's 12 postseason games, and his pesky defense on LeBron James in the second round won him many admirers, even as Miami took the next four games. "Some guys say all the right things and do none of them," says Thibodeau. "Jimmy is just the opposite. He doesn't say a lot, but he's always doing the right things."

The Bulls traded Deng in January 2014, creating an opening for Butler, but he was hampered by a right-foot injury. He entered last summer with an eye toward rediscovering the Tomball High scoring game he had abandoned at Marquette. Moving to Houston for the summer, Butler settled in with close friends, canceled his cable and Internet service, and worked out three times a day, slimming down from 245 pounds to 232 so that he could move more freely. He sharpened his perimeter shooting and his mid-post game, studied tape of Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant, and put himself through endless ballhandling drills.

The results have been superb: Butler is leading Chicago in scoring, his playmaking draws rave reviews from the coaching staff, and he remains a strong contender for the All-Defensive team. "He's always had the heart, and he's always had the toughness," says Miami Heat guard and fellow Marquette alum Dwyane Wade, "and now he's put it all together with his game."

James Harden, the NBA's unlikely MVP

There's evidence of his newfound confidence everywhere. Butler has attempted a career-high 14.3 shots per game, delivered in late-game situations and called himself Baby Mike—as in Jordan—during practice trash-talking sessions. He has also cultivated a distinctive hairstyle: shaved tight on the sides and long on top. "My hair is nappy, but that's my brand," he winks. "When I was in high school, people would make fun of you for that, and you would have to shave. Now I have a brand."

Butler's offensive emergence and defensive consistency have helped Chicago reach the top of the Central Division standings, despite injuries to Rose and Joakim Noah. But Butler's progress will almost certainly cost the Bulls a small fortune. Last fall they offered a contract worth more than $40 million over four years. Butler says a deal was "really close," but he chose to bet on himself instead. Next summer he's likely to weigh offers of $70 million over four years as a restricted free agent, though executive VP of basketball operations John Paxson has vowed to match them. "In terms of being a two-way player," says Thibodeau, "he's as good as it gets."

When Lambert talks to Butler now, she sees how wins and losses can still produce mood swings, how he remains reticent to open up about his experiences, how he uses laughter to mask his emotions and how he tries to find positive ways to channel his pain.

Lambert has done everything in her power to convey to Butler that her love for him is unconditional. She forbids her younger children from wearing other players' signature clothing and shoes because it would be "disrespectful." She flew her family to visit Butler and Thomas for Christmas in Chicago, and she takes joy in hearing them hoot and holler during late-night games of Spades and Bourré. She marvels at Butler's emergence, calling it "a living dream," and sends him the same text message before every game: "Good luck, Lovebug. I love you so much." Yet Lambert understands that Butler can't help but seek two more votes: those of his biological parents.

Butler's voice catches as he explains that his father has followed his basketball career over the years, and that the two men continue to work on their relationship. "I love my dad to death," he says, preferring to leave it at that.

Shortly after he was drafted, Butler reached out to Londa, and they coordinated their first sitdown in years. He says his mother is proud of his accomplishments, and he has spent time with her two other children during the off-season. "She's still my mom," Butler says. "I have a lot of love for her. There's no bad blood. We're family."

There's a photo, taken last August, of Butler with his long, left arm wrapped around Londa's shoulder. Both wear smiles and glasses, with Tomball concrete under their feet and fluffy clouds dotting the blue sky above. The town's forgotten son has become its favorite son, and he is solely focused on moving forward.

"Nobody is perfect, so no one should be condemned," Butler says. "How do I forgive? There's no reason to hate or dislike. I don't believe in that. Obviously, it took a while to get to that point. All of that history is a part of me being here, but the past is the past. I forgive everybody. I love everybody. That's that."