The New Colossus

Sneakers squeak on honey-colored hardwood. The gym, in Wisconsin, has a stage behind one basket, a volleyball marooned in the rafters, a bake sale in the lobby, a raffle in the retractable bleachers and a brass band playing “Louie Louie” and “Rockin’ Robin,” the timeless soundtrack of high school basketball in America.

When the victorious Knights of Dominican High—green letter jackets, white sleeves—board the orange school bus idling outside Shoreland Lutheran on a 27° school night in Kenosha, it could be any year in the last half-century, if not for the Beats pinching Alex Antetokounmpo’s temples like a laurel wreath, or the Amazon warehouse that slides by the bus windows on I-41. The building goes on forever, like the repeating cityscape in a cheap cartoon—a 2.4 million–square-foot monument to material desires, the consumer goods so central to American life that this facility and others like it are called fulfillment centers.

Antetokounmpo finds serenity in basketball, including the play after halftime, when he caught and dunked a lob from a half-court inbounds. “Alex lights up when he hears the word ‘lob,’ ” says Dominican coach Jim Gosz, though the 6' 7" senior also appreciates the hourlong bus ride with his buddies back to the suburb of Whitefish Bay up the coast from Milwaukee. “It’s fun to travel with the guys,” he says, and Alex has traveled farther than most, having arrived here from Athens in 2013, at age 11, when the Bucks selected his 18-year-old brother Giannis—then two inches shorter, 35 pounds lighter and 100% more obscure than he is now—with the 15th pick in the NBA draft.

That obscurity cut two ways. “I didn’t know much about the NBA,” says Alex, “but my brother told me he got drafted and we’re moving to the United States. I didn’t know Milwaukee, but I knew I didn’t want to go.”

On arrival, the boy was astonished by the size of American supermarkets—Wisconsin’s vast Pick ’n Saves and Woodman’s and Festival Foods—and the multifarious fast food options. After exiting the highway tonight, the bus follows a Boulevard of Broken Seams, aka Silver Spring Drive, a gantlet of Jimmy Johns, Taco Bell and Dunkin’ Donuts leading directly to Dominican. “Chick-Fil-A, Culver’s, Blaze Pizza . . .” says Alex, ticking off his favorite franchises, a hymn to the drive-thru, dollar-menu, fast food fever dream of American suburbia.

When at last he arrives home—to the red-brick five-bedroom in River Hills that he shares with Giannis; their mother, Veronica; and Giannis’s partner, Mariah Riddlesprigger—Alex doesn’t watch the Bucks-Pelicans game on TNT. (There, Giannis is amassing 34 points, 17 rebounds and six assists while laying waste to New Orleans and its talented rookie, Zion Williamson, in what will be the night’s lead story on SportsCenter.) Rather, Alex streams a Wisconsin Herd game, “to see my other brother,” 27-year-old Thanasis Antetokounmpo, a 6' 7" forward who has been on the Milwaukee bench for much of the season and is getting minutes tonight in the NBA’s developmental G League, which features another “other brother,” 22-year-old Kostas Antetokounmpo—Dominican High, class of 2016—who plays for the South Bay Lakers, on a two-way contract with the actual Lakers. Is it any wonder that Alex speaks of basketball as the family business, describing it during a break from practice at Dominican the following afternoon as a “job” and a “craft” and an “industry”? He is serious bordering on somber, and dripping with sweat.

“I used to be starstruck,” he says of his brushes with LeBron James and Kawhi Leonard and the other superstars he encounters with Giannis, who is himself the best player on earth right now, and the presumptive soon-to-be back-to-back NBA MVP, though the season was suspended indefinitely on March 11 because of the coronavirus. “But I’m hopeful to be in this industry, so I can’t be starstruck anymore. When I see them now, I’ve got to learn.”

“Family business?” says Thanasis, in another gym, on another gunmetal-gray winter day in Wisconsin. “I’ve honestly never heard that about us and basketball.” He smiles and considers the phrase. “No, I’d say sports is the family business.” In Nigeria, their mother, Veronica, was a high jumper, and father, Charles, played soccer. He died of a heart attack in 2017, in Milwaukee, at age 53. In tribute, Alex wore a custom pair of Nike Freak 1s—Giannis’s signature shoe, and the best-selling signature launch in the shoe giant’s giant history. They were emblazoned with a bit of wisdom passed down by Charles: always want more but never be greedy.

These days, the phrase provides some solace in Milwaukee. Though Christian Yelich, the Brewers’ star outfielder, just signed a nine-year extension to stick around, Giannis can become a free agent after next season. This current limboed season is unlikely to affect the service time of NBA players, which means the Freak could conceivably leave town for sunnier climes, if not greener pastures. (In the arcane economy of the NBA, the Bucks can still pay Giannis more than any other suitor.) He is in the third year of a four-year, $100 million deal and could sign an extension as early as this summer. And for the far-flung Antetokounmpo brothers—born in Greece to Nigerian parents—the family home has become this unlikely locale of Friday fish fries and drink wisconsinbly T-shirts. “For sure, for sure,” says Thanasis, standing beneath the Greek and Nigerian and American flags suspended from the rafters in the Bucks’ glittering new practice facility. “Home is where your family is. And my mom and my brothers are here.”

Thanasis was drafted by the Knicks in 2014 and played briefly for them, as well as in Europe and the G League before signing a two-year contract worth $3.2 million with the Bucks last July. On arriving in America, he too was amused by the size and scope of the supermarkets. “Like a shopping mall, you can get anything,” he says, and it’s unclear whether he’s talking about Pick ’n Save or America itself.

Like Charles, he guards against greed and self-aggrandizement. “That mostly has to do with the way we grew up, has to do with our culture,” he says. “Being from an African home and a Greek home, it’s different, in a good way. Obviously, everybody likes nice stuff, everybody wants to look good or whatever. The thing is”—he lowers his voice, as if sharing a confidence—“you don’t really need to get caught up in this.”

The Antetokounmpos have not succumbed to the undertow of celebrity that trails Giannis. And despite its occasional efforts at reinvention, including the sign at the airport welcoming visitors to “America’s Third Coast,” Milwaukee is not known for self-promotion, either.

Two days after the NBA suspended its season, Giannis and his family pledged $100,000 to the workers at Fiserv Forum, and the people of Milwaukee often return the love. When out and about, the Antetokounmpos make no effort to keep their fellow citizens at arm’s length. “No, no,” says Thanasis, wearing a pained expression. “Why? It’s nice to have people support you.” They’re approachable, selfless with selfies, and when they cannot be—“like at the movies,” says Thanasis, when people want a picture in the dark—they tell their admirers they’ll catch them next time.

“I think the people are [respectful] because they know we’re just one big family,” says Thanasis. “We’re open and not like this”—he holds his arms out as if keeping a mob at bay—“so they don’t feel like, Oh, my god, I’m not gonna see them again. You’ll see us again. We’re a big family, Milwaukee.”

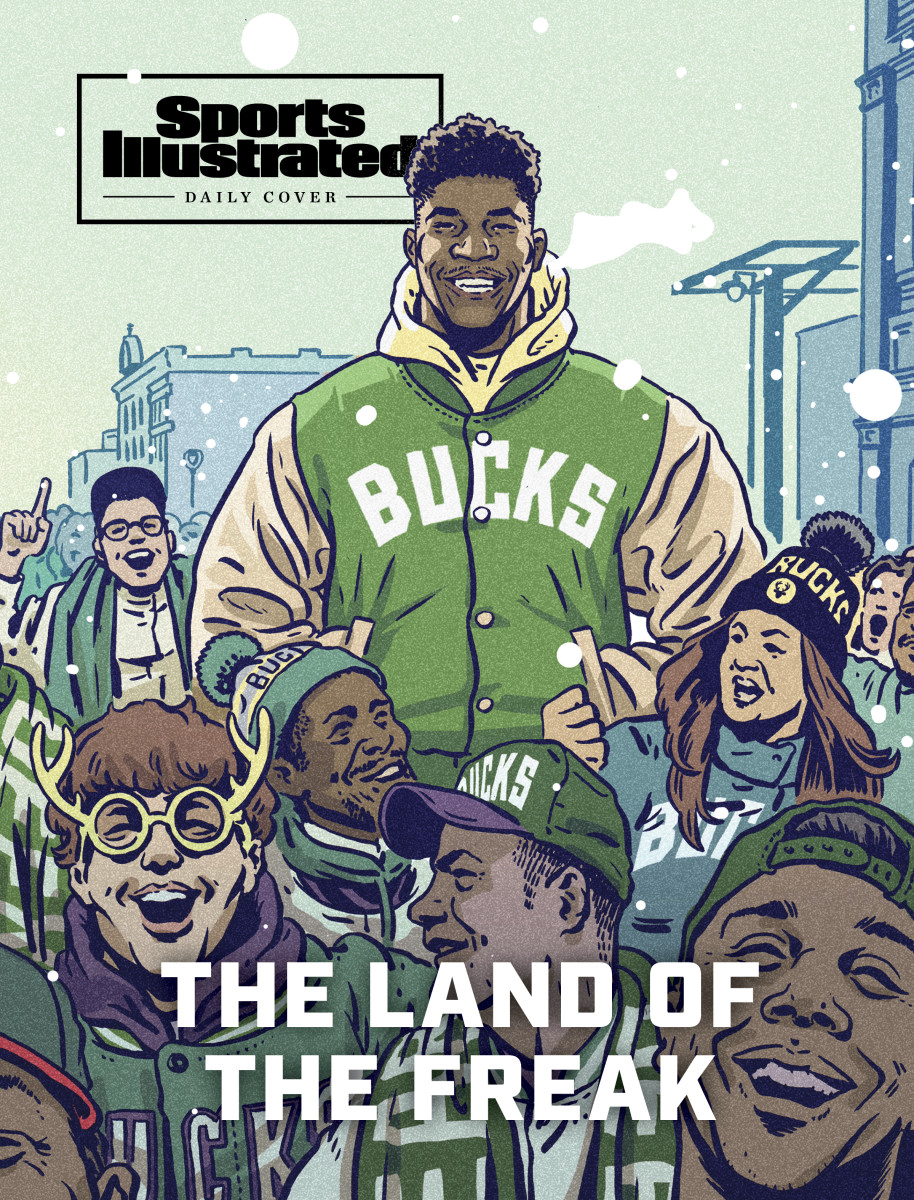

In Milwaukee, you see Giannis everywhere. He’s on that enormous banner stretched across the Fiserv Forum parking garage downtown, extending his wingspan—7' 3" in real life—as if trying to wrap his arms around the city. But he’s also in the smaller banner, just across from the arena, that makes no mention of him but doesn’t have to. Hanging on the side of the Turner Hall athletic club, it says, simply, immigrants welcome here.

Giannis covers one exterior wall of the Corner Market convenience store in Milwaukee’s Tippecanoe neighborhood, just north of the airport. Milwaukee artist Fred Kaems received a commission to beautify a brick wall facing a residential street, and in doing so he wanted to exemplify Milwaukee, celebrate multiculturalism and offer hope in a city historically polarized by race. “What is Milwaukee?” asks Kaems. “Who is important? Giannis isn’t from this city, but he’s continued to grow here, and that’s a great metaphor for the city. He’s growing as we do.”

Like the pigeon-befouled statue of Arthur Fonzarelli that stands, thumbs raised, beside the Milwaukee River downtown, Giannis is already a civic totem. The Greek Freak and the Bronze Fonz represent mythic figures often seen in the gymnasiums of southeastern Wisconsin. Giannis coaches the Dominican High fall league team. In the winter, as the Bucks’ schedule allows, he sits in a corner of the Dominican bleachers, hood pulled up like basketball blinders. Last season, after a Knights game 45 minutes away in Racine, Giannis stood outside the gym in January, signing and posing for 30 waiting kids. “I was that kid,” he often says.

He’s now a 6' 11", 242-pound, 25-year-old man, as long and lean as a Giacometti sculpture, which isn’t to say that he’s fully grown, because Giannis keeps getting better, improving significantly on last season, when he was the league’s runaway MVP. Ask Bucks coach Mike Budenholzer, who assisted Gregg Popovich for 17 seasons in San Antonio and thus knows the art of interview brevity, whether he has run out of ways to describe the Freak. Budenholzer is already forming the one-word answer “Yes.” If you persist and ask him to elucidate the player’s continued growth, he says with a smile: “You had to throw in, ‘Could you describe. . .’ ”

It is a happy problem, he knows, and Budenholzer gives it a shot: “It starts with his desire to improve and put in the work to get better, not just every year but every day. There’s a few things we look for as far as who we want to be”—work rate, attitude, a panoply of skills—“and he checks all the boxes. He has an incredible drive but also a humility to him, and an expectation that he can get better.” After a pause, Budenholzer adds: “Yeah, we’ll keep him.”

Budenholzer was speaking in Fiserv Forum before a February game against the Sixers, who had beaten the Bucks on Christmas Day. On this night, though, Giannis will go off for 36 points, 20 rebounds and six assists in a 112–101 win. It is Antetokounmpo’s fifth straight game with 30 and 15. He is the only player ever to do it besides Wilt Chamberlain, and the points come on a series of spin moves and dunks, midrange jumpers, plus one monstrous putback and a single three-pointer. It is another night of routine greatness, in a season of workaday brilliance, that has seen Giannis average roughly 30 points in under 32 minutes per game.

In the Bucks’ locker room afterward, Giannis and Thanasis sit at the Freak’s locker, speaking softly in Greek. After 15 minutes, Giannis rises to address the waiting media, which numbers a couple of dozen reporters even in small-market Milwaukee, given the Bucks’ chase for one of the best records in league history. “I can get a lot better,” Giannis says. A lot? This is a frightening prospect for opponents, as Antetokounmpo is already taking more threes this year, stretching defenses, though he’s still shooting only 31% from long distance. “I can be smarter,” he says. “I can be sharper. I can make better passes. I can make [a higher percentage of] shots—three-point shots, two-point shots. I can be better. That’s the mindset that I have. I still gotta improve.”

Then he rejoins Thanasis, this time at his brother’s locker, and the two speak softly again, now in English. The first word that best describes the tableau as they exit together is tender. The Sixers are headed back to Philadelphia, but this is brotherly love. “He’s my teammate on the court, but he’s also my brother out there,” says Thanasis, who made his first start of the season on Greek Night against the Nuggets in January and scored on an assist from Giannis. “And he’s my brother off the court, but he’s also my teammate, because we talk basketball all the time.”

“Just from being around them,” says Gosz, “I think Thanasis is the ringleader.”

“I hope I’m a good role model,” Thanasis says. “I try to be the best example to my brothers. I never want them to see me do something that I wouldn’t want them to do. That comes from my mom and dad. It’s the way we grew up. Try to set a good example and take care of yourself physically.”

Alex learned well. In January, Dominican played national powerhouse Sierra Canyon of Los Angeles, at the Hoophall Classic in Springfield, Mass., in a game billed as the sons of LeBron James (Bronny) and Dwyane Wade (Zaire) vs. the brother of Giannis Antetokounmpo. Sierra Canyon won 90–55. “If we played them 100 times,” Gosz says, “we’d lose 101 times.” Alex, who has received offers from Ohio University and UW–Green Bay but not yet decided whether he will attend college, had 13 points and seven rebounds while wearing the weighted vest of high expectations. “I took a big bite of humble cake out there,” he says, and that word, cake, suggests something higher in humility-calories than humble pie. “He’s a very pleasant kid, to opponents and teammates,” Gosz says. “He’ll show a temper but doesn’t have a mean bone in his body. He could live like a rock star around his brother, but he does his tasks here from 8 to 3.”

His temper flared after Dominican’s season-ending, triple-overtime, 103–102 playoff loss to Brown Deer in March, when Alex had to be restrained while charging at the departing referees, an incident recorded on smartphone and screened on local news, the kind of scrutiny that comes with his surname. The incident stood in contrast with the hereditary sense of purpose the brothers have largely maintained, so that even as the Bucks continue to pound opponents, a meat mallet forever flattening a pork chop, Giannis says: “We gotta put our heads down, stay humble and just keep going.”

Giannis is a soccer fan who supported Arsenal as a kid, in thrall to their French striker, Thierry Henry. After the Bucks beat the Hornets in Paris in January, in front of PSG stars Neymar and Kylian Mbappé, the latter was asked what he knew about the Freak, to which Mbappé replied: “People told me he’s a good person.”

But Giannis is also in possession of that indefinable quality that Mbappé might call Je ne sais quoi. “Cristiano Ronaldo, Messi, all these guys, they have something special,” says Thanasis. “When I say ‘something special,’ it’s not just their soccer. You know how you meet people and you have a conversation with them and you don’t really think about what they do, you just think they have something special? That’s Giannis. I don’t say this because he’s my brother. He has . . . something.”

Charisma? Magic? “Yes,” Thanasis says. “And it’s nice to meet people like this.”

“Segregation is a stated fact in every story about Milwaukee,” says Kaems, the artist, who grew up in Sherman Park, which made national news in 2016 for three nights of riots following the fatal shooting of a black man, Sylville Smith, by a black police officer (who was later found not guilty of first-degree reckless homicide). In January ’18, Bucks guard Sterling Brown was tased, thrown to the ground and handcuffed in the parking lot of a Milwaukee Walgreens at 2 a.m. after parking across two handicapped spaces. One of the officers on the scene was fired after later posting racist memes on social media. “Milwaukee is the most segregated, racist place I’ve ever seen in my life,” Bucks president Peter Feigin told a local Rotary Club that year, and the city’s metropolitan area remains, according to the Brookings Institution, the most segregated in the country. (During a panel discussion over NBA All-Star weekend in Chicago, Barack Obama told one of the panelists: “I want you to be a little more public, Giannis, because I think you have something to give in terms of giving back. And you can set an example for the people.”)

“That will take generations to change,” says Kaems. “But there is good stuff happening simultaneously.”

Should large gatherings resume by then, Milwaukee will be in the international spotlight in August, when Fiserv hosts the pandemic-delayed Democratic National Convention, and perhaps again, should that arena cohost a long-postponed NBA Finals in the heart of the so-called Deer District: the new bars, restaurants and apartment buildings surrounding the two-year-old arena, where even the fire hydrants are painted with basketball iconography.

Few things unite a city, however briefly and superficially, like a championship. Lakhwinder Singh, 54, owns the Corner Market, with its large mural of Giannis, and his younger son plays basketball. “I went to the last Bucks home game, saw Giannis,” says Singh, who came to Milwaukee from India in 1995. “It’s a small city,” he says. “A nice city.” His customers like the Giannis mural.

So far, there has been little public anxiety about Giannis’s potential departure in free agency, though the city has lost a basketball superstar once before. As with Giannis, Milwaukee and Kareem (Abdul-Jabbar) were on a first-name basis, until he left for L.A. in the summer of 1975 after six seasons with the Bucks, including the franchise’s only NBA championship (in ’71). “Milwaukee is not what I’m all about,” Abdul-Jabbar said then. “The things I relate to aren’t in Milwaukee.” The New York Times cited his “disenchantment with a city best known for beer and bratwurst.”

Forty-five years later, Milwaukee is perhaps still best known nationally for those two inexhaustible resources. A “Bratzooka” now fires rounds of cylindrical pork at Bucks fans in the Fiserv Forum, and a “Beer Me” button summons suds to the seat of any spectator who has downloaded the arena’s app. The Bucks offices are in the former Schlitz brewery campus, redeveloped as Schlitz Park, twinning beer and deer for the foreseeable future.

But Giannis is sweeter on another of Milwaukee’s enduring loves: professional wrestling. The late Reggie Lisowski—known to 20th-century wrestling fans as the Crusher—is commemorated in bronze in his native South Milwaukee; he’s holding a beer keg on his right shoulder, his left arm perfectly positioned for photo-op headlocks. On a cold day in February, someone has placed a Packers hat on his head.

“Always, always,” says Thanasis, of the brothers’ enduring ardor for piledrivers and camel clutches, kindled via TV during their Athenian childhood. “There was a lot of people [we admired].” He exhales deeply, loath to choose a favorite. “I could give you a top five: Undertaker, Stone Cold, the Rock, Eddie Guerrero—he was amazing. So many, so many. . . .” He gets a faraway look, lost in wrestling reverie, and forgets to names a fifth. But that night, before the Bucks take the court, in the neon-lit tunnel outside Milwaukee’s locker room, Giannis busts out the Cobra, the signature finishing move of the WWE’s erstwhile intercontinental champion Santino Marella, and applies it to teammate Robin Lopez.

They do this pantomime of professional wrestling before games, Giannis, Lopez and company, betraying no signs of anxiety over last year’s conference final exit to the Raptors, or of the unspoken F-word that is free agency. Giannis said before the season that he wouldn’t talk much about his contract, and for the most part he hasn’t. “When I thought about it this summer when I was sitting down with Thanasis and my family on the couch watching shows and all that, I feel that if you have a great team—and our goal is to win a championship and be the last team standing and get better each day—I think it’s disrespectful toward my teammates, talking about my free agency,” he said in September.

On this day, in the Bucks’ locker room, Giannis pronounces himself conditionally content. He and Thanasis have an endearing habit of repeating words and phrases. Adjectives issue from their mouths like paired animals departing Noah’s Ark. “Crazy, crazy,” Giannis will say of some spectacle. Or “Amazing, amazing.” Tonight, he says: “I’m happy, I’m happy that we’re winning.”

He is also happy to be winning in the hashtagged sense of the word, winning at life, in every conceivable way. In Athens, the Antetokounmpos famously sold DVDs to make ends meet before coming to America, a phrase that is hinted at on the Nike T-shirt Giannis wears after shootaround this morning: Every letter in the word freak is rendered in the tartan pattern of McDowell’s, the fast-food franchise from the 1988 Eddie Murphy comedy Coming to America.

Giannis came to America with his family in 2013, during the final season the Bucks were owned by Herb Kohl, who attended Washington High in Sherman Park. Kohl’s father, Maxwell, was a Polish immigrant who opened a grocery store that would become a chain of supermarkets, those dizzying American wonders. A chain of Kohl’s department stores followed. Kohl’s mother, Mary, also emigrated to America, from Russia. Herb Kohl served Wisconsin as a U.S. senator from 1989 to 2013, when he helped bring the Antetokounmpos to America. Alex was enrolled in Saint Monica’s, the Catholic middle school down the street from Dominican, where the boy had some initial difficulty navigating two intimidating new cultures: America and middle school: “It was much harder than high school,” says Alex. “In middle school, it was harder to fit in. A kid that age is not going to understand our family’s situation.”

That family’s story, even now, can be hard to fathom. Giannis calls it an “amazing dream” and an “unbelievable journey.” They’re not alone. “As the product of immigrants myself, I believe in the American dream: the notion of hard work, sacrifice, risk-taking and love,” says Kohl, 85. “That is also the story of Giannis’s family.”

And that family recently grew by one. Giannis and Riddlesprigger now have a son, Liam Charles, born on Feb. 10, making Alex, Thanasis and Kostas new uncles in a growing Nigerian-Greek-American family: the Antetokounmpos of Lagos and Athens and Greater Milwaukee.

“My happiness level is here,” Thanasis was saying on a cold winter morning in Wisconsin, raising his right hand several inches above his head, to roughly the height of his world-famous brother. “Our family’s happiness level is here.” He held his hand there for a moment and looked up, to roughly the height of his world-famous brother.