How Chinese Basketball Stalled Out—and What it Means for the NBA

As the novel coronavirus hurtled around the globe in mid-March, O.J. Mayo weighed his options. The former NBA swingman and No. 3 draft pick had been playing in a professional league in Taiwan, but the season was on hiatus due to COVID-19, and his team’s practice facility was closed. He briefly considered flying back home to the U.S., until he heard from friends and family how things had worsened there, too. “Then I got a phone call,” Mayo says.

It was from his agent, relaying word of closer, greener pastures: A club in the Chinese Basketball Association wanted to sign the 32-year-old for the remainder of the 2019–20 season, which at the time was scheduled to resume on April 15. From there, the decision was easy. The CBA had been shuttered since Feb. 1, but China, the epicenter of the pandemic, had long since flattened its curve, and the country was cautiously reopening after months of strict lockdown measures. “I was like, ‘Why not? I'm already on this side’ ” of the map, Mayo says. “Stay where things are basically calmed down.”

But on the same day that Mayo says he flew to Liaoning in northeastern China, home of the Flying Leopards, reports emerged that the CBA had delayed its restart until May. More inauspicious news arrived the next night, March 26, when the government announced that it was closing its borders to almost all foreign nationals. In this regard Mayo had barely beaten the buzzer, but several of his fellow “imports,” as the CBA’s limited roster of non-Chinese players are known, weren’t so lucky. “They were in the airport, on their way,” Mayo says, “and got stuck and had to turn around.”

Even for those like Mayo who successfully reached China, a hotspot for U.S. players thanks to its high salaries, posh perks and a (normally) short season, more limbo awaited. As a precautionary measure upon reaching Liaoning, Mayo entered government-mandated quarantine in a nearby hotel for 14 days. While there, he binge-watched countless hours of Netflix, received four coronavirus tests—two blood samples and two throat swabs—and worked out twice a day with a team trainer over video chat. But on April 14, less than a week after Mayo emerged with the medical all-clear to join his team, another hammer dropped: The CBA had determined that play wouldn’t resume until July at the earliest.

The summer date, still three months off, was daunting—this was no small delay. But Mayo opted to stay in Liaoning out of concern that travel restrictions could prevent him from returning to China over the summer. Still, without any games, his life has started to approach Groundhog Day levels of monotony. Each morning is reserved for on-court skill work or weightlifting, followed by lunch and several hours of team practice.

“Usually take a nap, then dinner, a movie, and sleep,” he says.

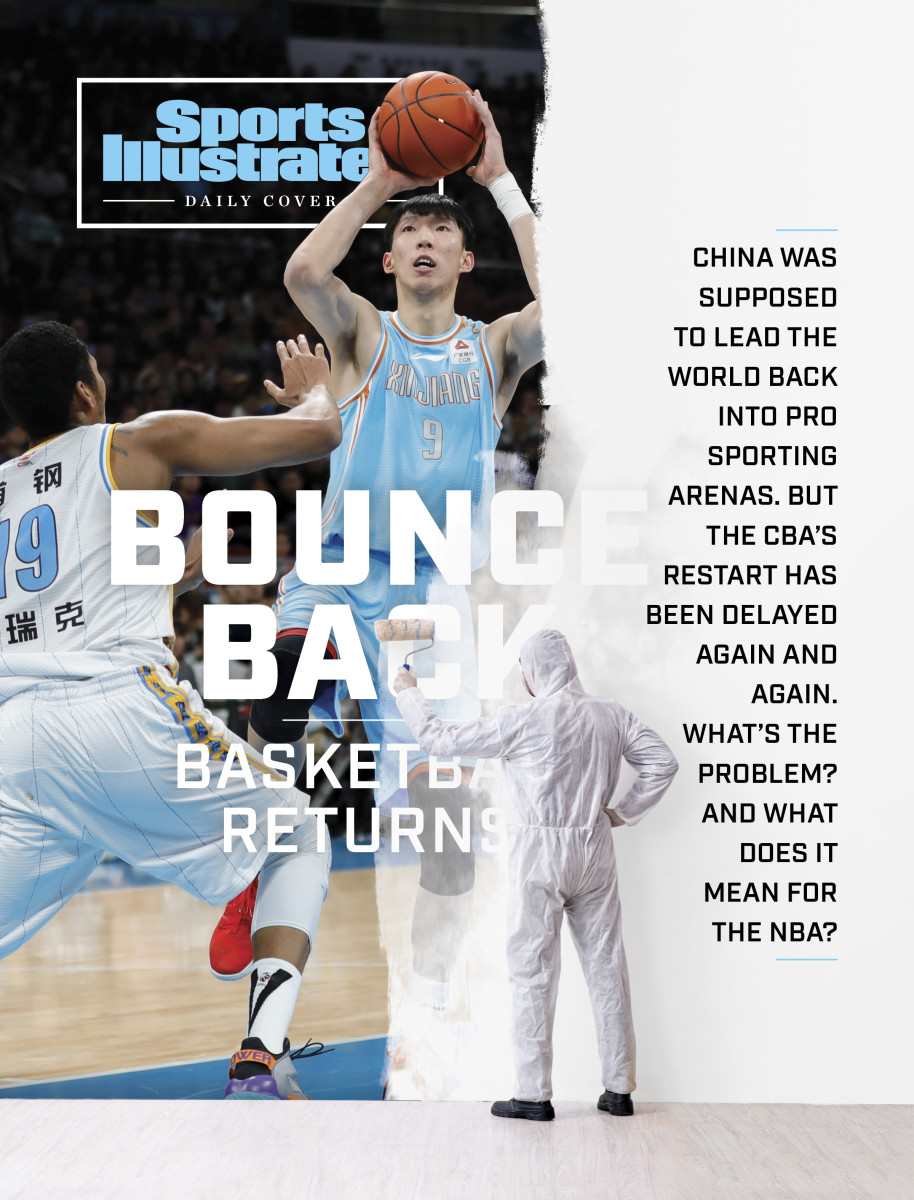

The CBA’s attempts to restart have taken on a similarly cyclical feel. As the world’s first major sports league to indefinitely suspend operations amid the growing pandemic, it was supposed to be a guiding light for other outfits looking to return—not to mention proof that the Chinese government, heavily criticized for how it handled the outbreak’s early stages, had brought life back on line.

Instead, as Korean and Taiwanese baseball leagues restart play (albeit without fans), the German Bundesliga readies to kickoff anew on May 16, and normalcy begins tiptoeing into arenas and stadiums across the world, the CBA has become a cautionary tale—a measure of the difficulties facing every league in the age of COVID-19. Its experience is especially relevant to its basketball brother, the NBA, which has floated restart plans similar to those sketched out by the CBA.

In China, scant official explanation has been offered for the fits and starts—or of when a final resolution can be expected. As one Chinese player put it to Sports Illustrated, “We stopped listening to all the rumors because there is a new message delivered to us almost every week.”

All the while, the CBA’s most famous, productive, and well-paid players—a list that includes former NBAers like Jeremy Lin, Ty Lawson and Lance Stephenson—have been stuck in the middle of the chaos. Some, like Mayo, are content to stay in China, collect a paycheck, and hold tight until July. Others have been stateside since February, either unable to travel or refusing to take the risk. Still more have been caught in between: fleeing to their home countries during the initial suspension, rushing to China and quarantining for the mid-April restart, and finally flying home again when the latest delay came down.

“It’s just a big disaster,” says one U.S. player, a high-scoring CBA veteran who requested to remain anonymous to avoid reprisal. “They called us back for nothing.”

***

Another player who answered the summons was Shanghai Sharks guard Ray McCallum Jr., a second-round pick to Sacramento who played 154 NBA games before heading overseas. After two weeks of hotel-room isolation, where meals were dropped outside his door and his only human contact came in the form of government health officials in hazmat suits administering twice-daily temperature checks, McCallum was released in early April.

To his pleasant surprise, he found that the city was creeping back to life sooner than he expected: For instance, when McCallum practiced with the Sharks for the first time again on April 2, he walked into the gym and began lacing up his sneakers while still wearing a medical face mask.

“My teammates were stretching, getting ready, and they had no mask on,” McCallum says. “They just laughed at me, like, ‘It’s O.K., Ray, everybody’s safe in here, it’s all good.’”

And things really did seem that way. “I was a little nervous,” says McCallum, who had been waiting out the hiatus with his father, a Tulane assistant coach, in New Orleans. “I was thinking, ‘Basketball is a contact sport, how are these practices going to go?’ But once we got playing, that went out the door.” Since then, the Sharks have been holding normal workouts at their facility, often twice a day and at a pace so furious that it reminds McCallum of training camp, minus the water breaks that now double as handwashing sessions, and the temperature scans that are mandatory before stepping onto the court.

“I’m here, I’m back,” McCallum says. “My main focus is to finish this thing out.”

He pauses.

“If it happens.”

The perpetual limbo is unsettling enough. But more than a dozen conversations with CBA players, coaches, team officials and agents have revealed a deeper frustration with how the league has yo-yoed from decision to decision amid the COVID-19 crisis. The issue is not the CBA’s caution—“If we can keep people safe by delaying our league and holding out on competitions for a second, we should,” says Mayo—but the uncertainty and lack of transparency that’s resulted in such a mad scramble for so many.

“In my opinion, I felt like they were rushing to try to start the league when they weren’t going to start anyway,” says Zhejiang Golden Bulls guard Marcus Denmon, a second-round Spurs pick out of Missouri in 2012. “For what reason? I’m not sure. But I feel like for them to say, come over here to ground zero during this pandemic, without even a guaranteed date to start, put you in jeopardy by making you get on a plane and travel … I didn’t think it was fair for the players.”

Although communication to the imports has been sparse—the language barrier doesn’t help either; most can’t simply call up their GM and complain—they did receive word of a plan for the April 15 restart: The league’s 20 teams would be split into two central sites—one in the northeastern port city of Qingdao and the other down south in Guangdong—where players would be tested frequently for the coronavirus and live in a CBA-only hotel while playing in a stadium in front of limited team personnel (up to 50 per game) and no fans.

When the season was frozen in late January, each team had 16 games remaining before the playoffs. Some players, including Allerik Freeman, a U.S. guard who plays for the Shenzhen Aviators, saw schedules indicating that the rest of the regular season would be played with this bubble format, similar to the publicly floated NBA blueprints that would take place in Las Vegas or at Orlando’s Disney World. “Basically, it was 16 games in less than 30 days,” Freeman says. “A lot of back-to-backs, three in a row, no more than one day off in a row. Some games at 1 p.m., some at 5 p.m., some at 9 p.m., really just all hours of the day.”

Other players and execs, though, recall hearing that only eight games would happen at these central locations, after which the CBA would reevaluate whether it was safe to resume the normal home-road schedule with travel. Of course, as one team official notes, this scenario presented other obstacles: “If you have a home-away format, and you still had some cities that have quarantine, if you leave the city and come back, you’ve got to do a 14-day quarantine.”

Regardless, the plan never came to fruition. When April 15 rolled around, rather than celebrate a restarted league, CBA CEO Wang Dawei gave an interview with the state-run media agency Xinhua in which he discussed how roughly one-third of “middle and senior executives” at CBA headquarters had recently taken “voluntary” pay cuts starting at 15%, including a 35% reduction for Wang himself. “This epidemic … has shown us that, in this early period of China’s professional league development, facing off against the sudden outbreak of the epidemic, there are still some problems that we will need to resolve,” Wang said, according to a translation provided by an SI researcher.

Here Wang was strictly speaking about league economics, but other issues had already emerged regarding the imports. Denmon’s big beef is over the ramifications he was told he would face if he didn’t return to China: not only withheld salary, but a possible multiyear ban from the league. Multiple sources say these threats were never communicated in an official memo, but rather through the shadowy game of telephone that often defines information flow in China. (The CBA did not respond to a request for comment for this story.)

But when Denmon went to fly back to Zhejiang from his home in Kansas City in late March, toting two suitcases full of granola bars, video games, exercise bands and other provisions for his upcoming quarantine, he discovered at the airport that China had just closed its borders to foreigners. “I can’t say I dodged a bullet, because all of the Americans who did go back, they’re not sick or ill. They’ve just been there for no reason,” Denmon says. “But who knows, maybe I could’ve been on a plane with someone who was sick. What I can say is this: I felt that it was premature and selfish to decide on those types of rules.”

Though Denmon was turned away in transit, he says that Zhejiang has withheld two months’ salary, worth several hundred thousand dollars. But even those getting paid are feeling the strain. As the only U.S. import to stick around in China through the peak of the coronavirus outbreak in February, Freeman was rewarded with a renegotiated contract and a good-soldier bonus. Now he is back home with his family in Palo Alto, having flown there with the Aviators’ blessing, battling the uncertainty. “I’m very hopeful. I definitely want to finish the season,” Freeman says, adding, “I think it’s just time to make a decision.”

***

So far, what few decisions the CBA has made haven’t been accompanied by much transparency: The last official coronavirus-related statement on the league website was posted during its Lunar New Year break on Jan. 24, announcing that games would be suspended starting Feb. 1.

One clear turning point was a March 31 announcement—a day after the rescheduling of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics—by China’s General Administration of Sport, declaring that “marathons and other large-scale activities, as well as sports competitions and other activities that draw large crowds, shall temporarily not be resumed.”

Since any CBA restart would have to be approved at the highest levels of Communist leadership, it’s safe to say that the government has not given the thumbs-up to such a plan. Asked to explain the delays, one team executive all but shrugged in replying, “The Ministry of Sport wasn’t comfortable yet.”

“It’s in Yao’s and the league’s best interest to get started,” says one former CBA team executive who now works in an advisory role with his club, referring to CBA chairman Yao Ming. “The league has streaming deals, TV deals, sponsorship deals with businesses. If you cancel the season, it’s not good for the league. Nobody wants to cancel. But at the end of the day it’s not up to them. The central government or the sports ministry isn’t going to risk putting live events on in the middle of a pandemic.”

Still everyone is watching for lessons. Just this week, the Nuggets, Blazers and other NBA teams were permitted to reopen their facilities for players amid relaxed local health regulations (despite COVID-19 cases still being on the rise in many states). No doubt this is a significant step on a long road, but the CBA players also know all too well that a few group shooting drills and shuttle sprints are not a sure sign of games to come.

One CBA team executive with NBA ties says he has been fielding frequent calls from former colleagues in the U.S, inquiring about the Chinese league’s attempts to restart: What are the necessary precautions? What can we learn? The “number one” lesson from the CBA for any sports league, he says, is simple.

“Don’t hurry,” the executive says. “China initially wanted to hurry. Then they got more information about the virus and they slowed it down.

“The other thing is this, and this is very important: It changed daily. They may say, this is a good idea, and then the next day rethink it. I think you’ll see that with the NBA.”

Admittedly, comparing the NBA and CBA is imperfect for several reasons. On the one hand, no CBA team travels privately, either flying commercial or riding the country’s high-speed rails, which means that a normal home-road schedule would presumably pose increased risks. On the other, tests are already readily available in China; American sports leagues have cited having enough as a threshold issue, especially without a vaccine. Also, China’s authoritarian government has enacted strict measures that are helpful to the CBA’s ultimate goal of restarting play: Most smartphones are now equipped with a government tracking app that analyzes peoples’ travel patterns and displays a color code related to their health risk, allowing them to enter subways, malls, restaurants and other buildings. And unlike in the NBA, where players can bargain through their union about bringing loved ones into the bubble with them, domestic Chinese players in the CBA lack such strong representation; in any case, most of them live in dorms or team apartments, away from their families throughout the season. In other words, whatever the CBA—and, by extension, the General Administration of Sport—ultimately says, goes.

Of course, there is one thing that the leagues do have very much in common: the indoor setting, tight quarters and sweaty intensity of professional basketball. "While sports like baseball and soccer involve multiple people touching the same object, and close contact, the frequency of that close contact is less in baseball and the frequency of touching the same object is less in soccer,” says Shira Doron, hospital epidemiologist at Tufts University. “When you combine how often basketball players are clustered together and how often they touch a single ball, the risk of transmission between basketball players is likely to be higher than that in many other sports."

For most sports league, though, says Zach Binney, an epidemiologist at Emory who specializes in athlete health, the problem isn’t the game-play, but the logistics: “The challenges of holding contact sports are dwarfed by the challenges of holding team sports in the first place,” he says. Even under the CBA’s bubble scenario, or a situation in which LeBron & Co. are holed up at Mandalay Bay, a staggering number of coaches, trainers, referees, scorekeepers, camera operators, drivers, chefs, hotel employees and other back-of-house workers are needed to support the players on the court. And what happens if someone happens to sneak out of the closed system, catches the coronavirus, and brings it back inside?

No matter how optimistic the leagues in Germany, South Korea and Taiwan may be about restarting, the experiment hinges on avoiding another Rudy Gobert. “If even one case gets into a biodome, you’ve just lost all you’ve put into setting it up,” Binney says. “It’s no longer virus-free.”

So where does the CBA go from here? No one is entirely sure. A mid-April article in the state-run China Daily floated both a “possible restart in July and possible cancellation of the season.” The league is hoping to avoid the second scenario—the Xinhua article that included CBA CEO Wang Dawei's interview on his league's delay asserted that, “Even if there is only a 1% chance of the season resuming, the CBA and each of the clubs will surely give it their 100%. Canceling this season is not the CBA’s choice right now.”

And so another game of telephone has begun. Mayo’s would-be GM in Liaoning, Li Hongqing, caused a minor media stir by suggesting that games resume with only Chinese players and no imports. (To promote domestic talent, CBA teams are already limited to one foreign player on the court at a time in the first and fourth quarters.) One American assistant coach, Kareem Hodge of Fujian SBS, meanwhile says that he’s been told to expect a “big government meeting this month” to determine whether the CBA can ultimately proceed with fans in the stands, and whether it can resume its normal home-road schedule. “Our club is currently on break,” Hodge says, “So we will be back in the middle of May and we’ll see if there will really be a season.”

An agent with several CBA clients, meanwhile, indicated to SI that two scenarios for that restart are being discussed, pending approval from Beijing: finishing the full remaining schedule from July 1 to Aug. 31, or finishing everything in July with a shortened playoffs. Of course, all of this would likely remain hypothetical if the borders remain closed, or a second wave of the coronavirus hits China.

“I call July 1 a target date,” one CBA executive says. “If they can start a few days before, they will. But thus far, no one has set a drop-dead date, which I think has to be the next deal.” After that, he says, the question becomes, “When are we going to cancel?”