Everything’s Just Peachy

Like many, David Goldstein took a long, winding route on the way to becoming a Hawks fan.

He grew up in Birmingham as a loyal NBA follower despite not having a team, then moved to Colorado for college. After graduating, he took a job in New York City, where he’d live for six years. In 2009, he went back South and put down roots in Atlanta, a city he’s lived in for about 12 years now.

Goldstein, a 39-year-old who owns a sports video production company, maintained his love of basketball throughout his time moving around the country. But when he planted himself in Atlanta, he didn’t feel the urge to invest emotionally in any of the local sports teams. “When I got here, I couldn’t have cared less about the Hawks, the Braves or the Falcons,” he says. “I’d go to games as an observer, to see Kevin Durant when the Thunder came in town and stuff like that. I think a lot of people here in Atlanta were like that, where we mostly wanted to see the star players and other teams when they’d come through and play.”

The Hawks’ magical, egalitarian run in 2015, when they came out of nowhere to win 60 regular-season games without a superstar on the roster, converted Goldstein and scores of others into fans of the club. Yet reality swept in quickly in the form of a conference-finals broom. Without a ceiling-raising superstar like LeBron James, who thrashed the Hawks that entire series, Atlanta would likely always be left in the dust.

Eventually, the Hawks’ front office reached the same conclusion. By the summer of 2017, Atlanta had made the playoffs 10 straight times, the longest active streak in the conference, without reaching the Finals. With seemingly no potential, a limited fan base and no clear pathway to land a star, Atlanta blew things up in hopes of rebuilding better.

Fast forward to now, and fans like Goldstein—who’d merely dipped their toes into Hawks fandom before—have signed on as season-ticket holders, feeling that this might finally be Atlanta’s moment. Because not only are the Hawks back in the playoffs. For the first time in nearly 30 years, they have a jaw-dropping star, fueling hope that something meaningful might be on the horizon for a club that’s been overlooked for much of its existence.

One could unfurl an entire list of reasons that the Hawks—who ranked 20th or lower in the NBA in home-attendance percentage for nine consecutive years from 2011 to ’19—have struggled to draw fans.

There’s the fact that Atlanta is far more transient than most major U.S. cities, leaving transplants like Goldstein—who have no lifelong affiliation with the local clubs—less likely to become supporters. There’s the city’s natural pecking order, which naturally gives the Braves (who were dominant for a decade and a half while playing every game on their owner’s network, exposing them to a national audience) and the Falcons (who play in the nation’s most popular league) a leg up. Georgia football is a factor every fall. And since its founding in 2014, soccer club Atlanta United has become the hottest ticket in town, not only selling out regularly but also building a season-ticket wait list thousands of people long. But it’s difficult to compare teams like the Hawks and Braves; not every team is competing for the same group of fans.

“Between where the Hawks and Braves games are played, and the age of the people who make up the crowds, it’s two different fan bases. The Hawks’ fan base skews younger, and is much more urban and racially diverse than the baseball crowd,” says Princeton University history professor Kevin M. Kruse, the author of White Flight, which examines the racial and political impetus behind white people moving from Atlanta to its suburbs en masse in the 1960s and ’70s. “Really, from the time the Hawks first got to Atlanta [from St. Louis back in ’68], they’ve always been tied in with the racial politics of the state.”

Divisions between the city and its suburbs have been on display in recent years—both politically, and in a sports sense. Since 2005, a number of wealthier Atlanta-area neighborhoods essentially have voted to form their own cities, a move that gave them separate, improved municipal services while also draining Fulton County’s tax base of tens of millions of dollars per year. And as the controversial suburban secession movement got underway, the Braves, too, began making arrangements to leave the city by bidding farewell to their relatively young stadium near downtown, Turner Field, to build a brand-new one in suburban Cobb County, where the bulk of their fan base lives. The team moved there in ’17.

In 2012, at the height of that movement, then Hawks majority owner Bruce Levenson sent an email to other team executives, saying he worried that fans’ arena experience—from cheerleaders, to the hip-hop music, down to the Kiss Cam—was too urban to draw affluent white ticket buyers to games. His message stated that “the black crowd scared away the whites and there are simply not enough affluent black fans to build a significant season ticket base.” After the email went public in ’14, Levenson apologized for the message, which suggested white fans were more valuable than Black ones, and sold his stake in the team.

If anything, the franchise has only leaned into the city’s culture even more since owner Tony Ressler took over in 2014. Rapper 2 Chainz and rap group Migos, both area natives, sit courtside to take in games (2 Chainz is a co-owner of the Hawks’ G League team). The newly renovated venue features rapper Killer Mike’s Barbershop, which is positioned right above the lower bowl and allows fans to get haircuts as they watch the game. The hip-hop tunes of Sir Foster, the most unique organist in the sports world, boom throughout the stadium. In surveys, fans have ranked Hawks games as the No. 1 experience in the league the past two seasons.

“You have to hold a mirror to your city, and this is our city,” says Hawks CEO Steve Koonin, another Atlanta native. “That’s our audience. So instead of trying to go for white, middle-aged fans like myself, we market to an audience that rarely gets marketed to. By no means are we exclusionary. The majority of our ticket-holders are white. But it’s a very different audience, that’s uniquely Atlanta.”

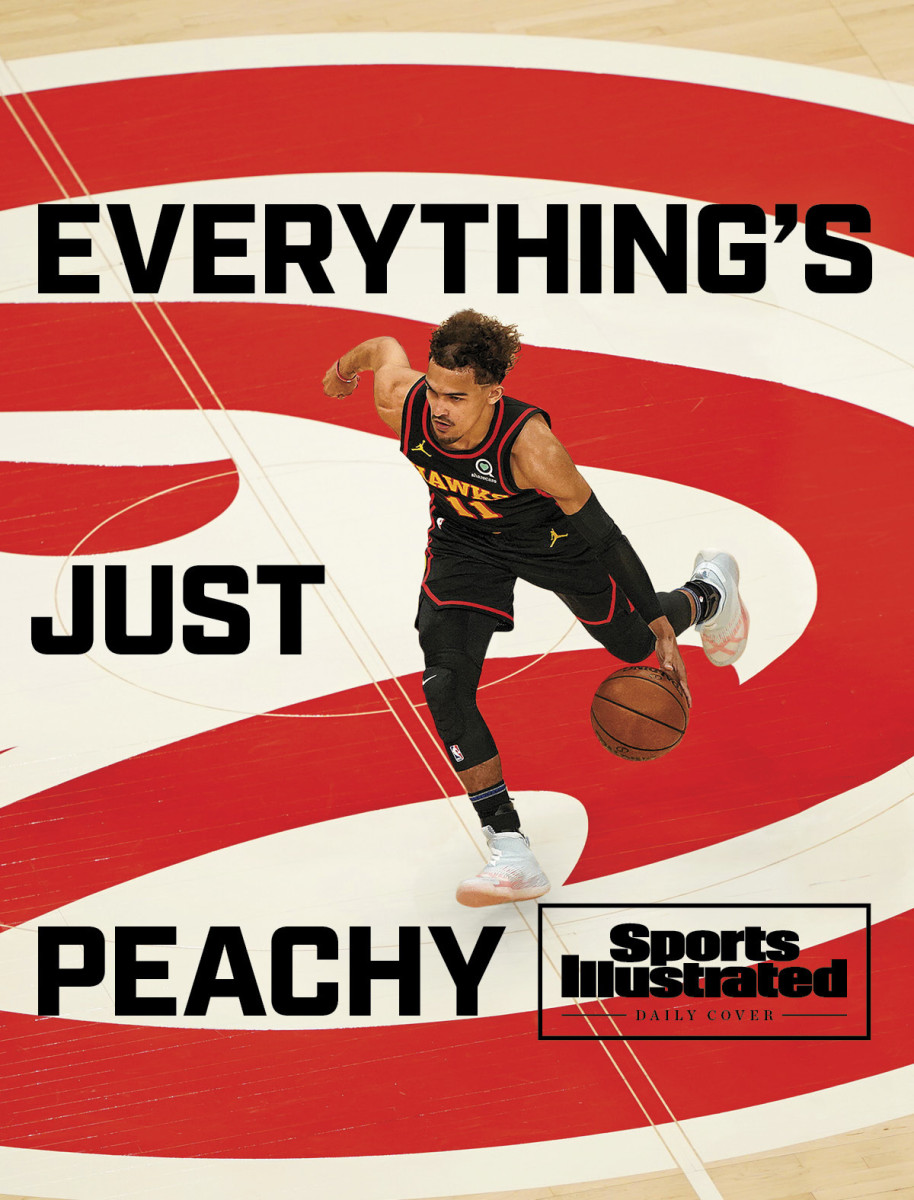

Yet few of these things, if any, would make a difference to the average person if it weren’t for Trae Young.

From Henry Aaron and Deion Sanders to Chipper Jones and Michael Vick, the city of Atlanta has long enjoyed its larger-than-life sports stars. But the Hawks went a few decades without one.

Sure, the Hawks had Joe Johnson, a seven-time All-Star who could quietly score in one-on-one situations with the best of them. But he was the quietest star possible, doing just enough to keep the Hawks in the middle of the pack, but not quite doing enough to push them beyond that. The Hawks paid him handsomely—Johnson was even the highest-paid player in the NBA at one point—but he didn’t have an electrifying smile or personality. And for all his talent, he wasn’t putting casual Atlanta fans in the seats.

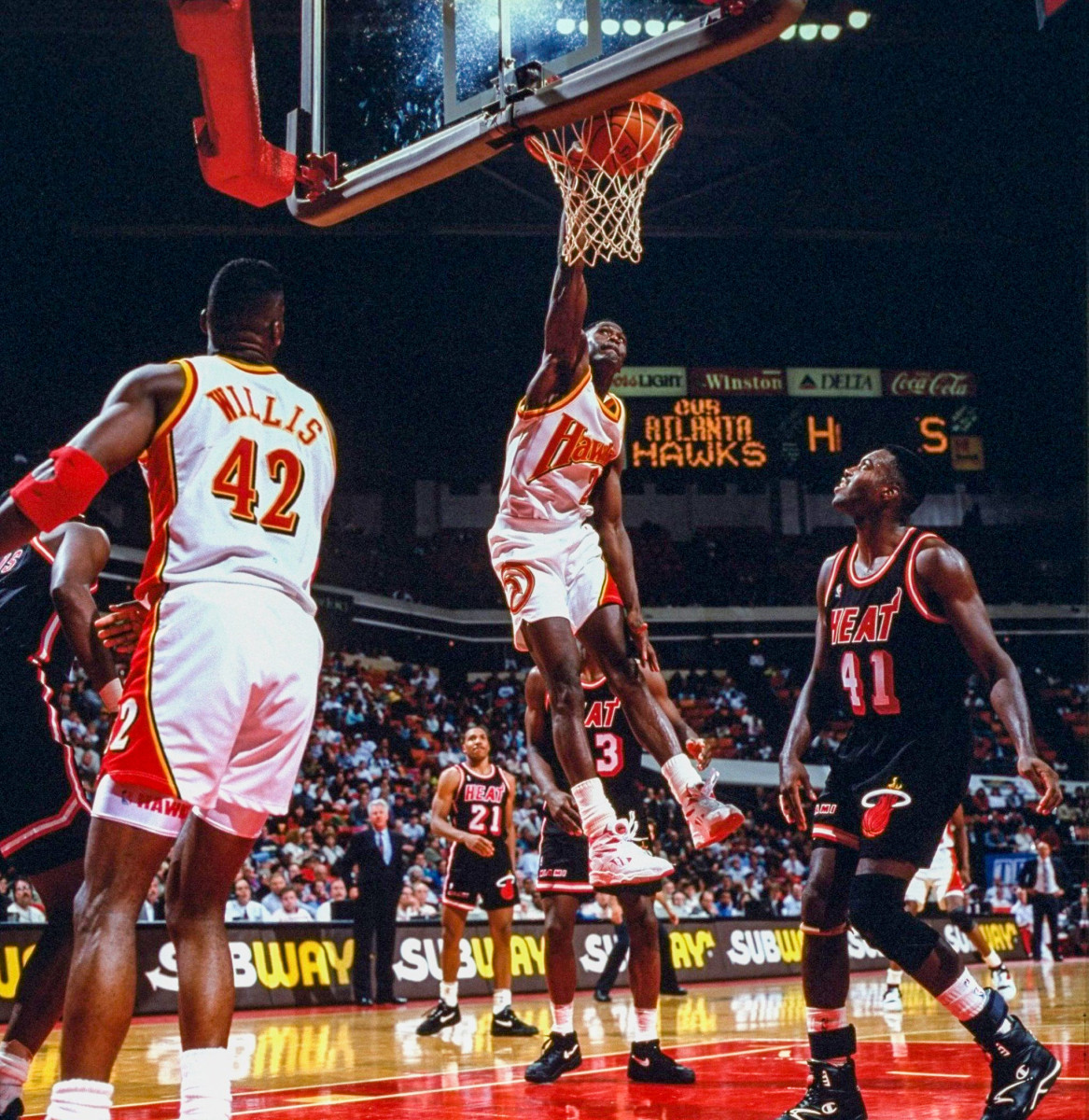

Here’s one way to look at just how long it’s been since the Hawks have had a superstar. You have to go back 28 years, to Dominique Wilkins in 1993, to find the last time Atlanta had a player finish among the top 10 in league MVP voting for a season. That’s not only the longest dry spell in the NBA. It’s a full 10 years longer than the Nets, who have endured the league’s second-longest drought.

“It’s been awhile,” says Wilkins, when told of the stat. “And it’s weird, because the city’s always had these iconic sports figures. But it’s a good feeling to know things are finally coming back around.”

Young and his team still have more work to do to catapult him into MVP talks. (He narrowly missed the All-Star team this season.) But if the last three decades have been a superstar desert for the Hawks, the diminutive guard has been a literal splash bucket to quench the club’s thirst.

Still just 22, Young has the impromptu passing ability of a Harlem Globetrotter and the long-distance shooting range of Robin Hood. Of the six players with the audacity to attempt 25 shots from 30 feet or more this season, only Stephen Curry (37.4%) knocked down a better percentage than Young’s 36.4%. And while he takes plenty of shots from other ZIP codes, Young is active in the paint, and made more free throws than anyone in the league. He’s become most known for his scoring (25.3 points this year) but ranked second in the NBA in assists per game. Young’s become highly annoying to defend. If you stay back too far on a screen, he’ll pull up from 40. Come up too much, and he’ll burst into the paint and either loft a floater or throw a lob for center Clint Capela, which flat-out deceives rim protectors, because the lobs look like floaters, too.

Even if you play him perfectly—closing out just enough to deter the long triple, and recovering enough to catch up to him before he gets off the floater or the lob—the floor general still might get the best of you. Like Chris Paul, he’s perfected stopping on a dime to prompt trailing defenders to crash into him.

Most impressive to those who work with Young: He’s quickly adjusted to the club’s improved rotation, realizing that the upgraded talent around him can only make him more difficult to stop down the stretch.

“They talked about this with Michael back in the day when he first came into the league: He was putting up a lot of numbers before Phil Jackson came in with the triangle,” says Hawks coach Nate McMillan, whose midseason takeover turned the team’s season around. “[The triangle] forced him to move the ball around and get other players involved, because he really hadn’t had a lot of [team] success. That’s part of the growth with a young player. Trae’s still trying to establish himself. He came in as a guy that could score and create offense. But when you’re trying to take that next step—win games—you’re not going to be able to do it by yourself. The team’s brought in enough talent to win games, and he has to learn to use the talent that he has. They have to form that chemistry on the floor, but I see them starting to do that.”

Much like Young has been the focus of opposing defenses—ranging from aggressive traps and even occasional box-and-one looks—he’s generated massive interest among a new wave of Hawks fans.

Chris Keith, a 50-year-old health-care administrator who lives in Alpharetta, just north of Atlanta, says the club was barely on his radar years ago. “After Dominique, they kind of became an afterthought,” he says. But then Keith’s 12-year-old son, Carter, grew more intrigued with the sport after participating in church-league basketball.

“I introduced him to the NCAA tournament [in 2018] when Trae was in it. Then he wanted to watch the draft for the first time that year. And the Hawks ended up with Trae. Now, my son has all the jerseys.”

Keith indulged his son by taking him to a handful of Hawks games each of the past few years. After a while, it made more sense to become a season-ticket holder. “I do feel like I’m on an island a little bit,” he says, adding that the rest of his suburban neighborhood is full of die-hard Braves and Falcons fans, with fewer Hawks supporters. “But I see a lot of Trae Young jerseys on my son’s friends. In a short amount of time, the Hawks became my family’s life. We went from casual watchers to living and dying with it.”

Many wanted the Hawks to use their 2018 first-rounder, the third pick, to take Luka Dončić, the six-foot-seven Slovenian guard who was being described by many as a potentially generational prospect. When Atlanta passed him up, fans didn’t initially understand the Hawks’ choice.

“I was at the [Hawks’] draft night party that night, and I think a lot of us were pretty distraught. We kind of couldn’t believe it was happening,” says season-ticket holder Will Balkcom, 27, who lives in the city’s Buckhead neighborhood. “We knew how good Luka was. We’d seen Trae’s college highlights and knew he could play. We just worried about it. But in the weeks and months that followed, I understood it more in hindsight. In a city like Atlanta, with the players that we’ve historically latched onto, Trae fits in right into that category.”

Fans began to feel Young’s star power could generate a greater level of magnetism. And between newer ticket-holders like Jessica Mercon (whose 12-year-daughter treasures a silicone bracelet Young took off and gave her after a game) and Andrew Hill (who says he’ll stay on as a season-ticket holder despite his family’s plan to move four hours away to Tennessee soon), that appears to be true for a number of people.

The Hawks don’t exactly run away from the idea that Young’s marketability was a factor. While general manager Travis Schlenk got extra value out of passing on Dončić—Atlanta was able to get an extra first-round pick that became Cam Reddish by trading down with the Mavericks—Koonin says he was adamantly in favor of taking Young, and that his interests went beyond just basketball.

“Travis will tell you that, for his part, he was looking for value. Meaning, we like Trae a lot, and we like Luka a lot. But getting another lottery pick was the tipping point,” Koonin says. “But the business side, we raised our hand and we said, ‘Trae.’ … Luka is an incredible player. I wish we had them both. He’s fantastic. Trae is on the path to superstardom, but for more than what he can do on the court. We saw in Trae somebody who was a dynamic player who had a real chance to connect with fans on many levels.”

Koonin is quick to add that his business-centric point of view about Young “means jacks--- to Travis.”

(“Less than zero,” he says.) And he understands the Hawks would likely be in a good place regardless of which player the team had taken. But he also points to a key figure. “Our youth jersey sales went up 1200% with Trae,” Koonin says. “He’s helping us create an emotional connection with our fans.”

Part of that was likely Young’s visibility as a high-profile prospect who’d become must-see TV at the college level, while Dončić was still an unknown to the average American fan. And it’s hard to imagine the team didn’t see an opportunity to market Young to one of the nation’s largest primarily Black cities.

In talking about Young’s impact on youth fans, Koonin mentioned Curry—whom Schlenk worked with in his prior stop with the Warriors—and how Atlanta had to open its arena earlier than usual whenever Golden State was in town. Fans would show up hours before tip-off, just to watch Curry’s otherworldly shooting routine. And on some level, Koonin hopes, if not believes, that Young can inspire the same sort of fan intrigue with his own flashy skill set.

The question now, of course, is what comes next for the franchise, which owns the NBA’s second-longest title drought, and hasn’t won the championship since moving to Atlanta five-plus decades ago.

At 25–11, the Hawks tied for the NBA’s third-best mark after the All-Star break, an affirmation that the club—which spent big last offseason—can more than hold its own when it’s healthy. Just as important: Atlanta now has a clear-cut blueprint—ample shooting, solid secondary ballhandling, plus a top-flight rim protector and pick-and-roll partner—for how to build a winner around Young’s relative shortcomings.

It bodes well for the future, which makes this feel fundamentally different than the 60-win season in 2014–15. Fans often packed the stadium that year, giving the club a franchise-record 25 regular-season sellouts. Yet there was a LeBron-sized obstacle in the way back then, and a feeling that those Hawks veterans were at the absolute peak of their powers. The current team’s youth brings more long-term hope.

The team says its local television ratings were up about 10% this year from last season, a jump that sounds ho-hum until you realize that 2019–20 numbers were already up by almost 50% from the season prior. The ratings are still toward the low end of the league. But it’s clear that Young has the city engaged in a way it hasn’t been in years.

“I thought we could do it [in 2015] without the star player, and with team basketball. But we learned quickly that wasn’t enough,” says 28-year-old Lovejoy resident Dominique Hill, a longtime Hawks supporter who recently bought a ticket package. “Having that star player with such a young team makes this feel different. Like, I’ve got a friend out here who’s a Celtics fan, and I’m not showing no mercy. I told him it’s never too late to convert to the Hawks. It’s a good feeling after all those years where our home games felt like they were on the road, because of who the majority of the crowd was rooting for.”

The club will get a plum opportunity to earn the national relevance it so desperately craves with a first-round matchup against the big-market Knicks, who won all three contests with Atlanta during the regular season. (One of the Knicks’ wins came last month when the Hawks blew a late-game lead after Young had to be helped off the floor at Madison Square Garden with an ankle injury.)

If there’s any irony here, it’s that the Hawks will again have an abundance of empty seats during their postseason run, despite being more relevant than they’ve been in years. “Obviously we’d rather not have our first taste of [postseason] in COVID circumstances,” sharpshooting Hawks wing Kevin Huerter says.

But for the first time in decades, there is a growing hope that the seats could be full soon on a regular basis. Because if you build it with an icon, chances are the stargazing Atlanta fans will eventually come.

More NBA:

• Cam Payne's Career Is Back From the Dead

• How Dejounte Murray Found His Way

• What Happened to Coach-Star Relationships?

• Utah's Journey from Dysfunction to Dominance