Coin flips, sharps and safeties: Super Bowl Sunday stories from Las Vegas

As part of our countdown to Super Bowl 50, SI.com is rolling out a series focusing on the overlooked, forgotten or just plain strange history of football’s biggest game. From commercials to Super Bowl parties, we'll cover it all, with new stories published and archived here.

The most improbable start to a Super Bowl may have occurred two years ago, when on the first play from scrimmage, Broncos center Manny Ramirez snapped the ball over quarterback Peyton Manning’s right shoulder and out of the end zone for a Seahawks safety. The play underscored the raucous noise at MetLife Stadium and a lack of preparedness in Denver’s offense, and it sounded the tocsin for a 43–8 rout by underdog Seattle. In Las Vegas, that safety did something else.

“People had money on all kinds of bets related to that play,” says Art Manteris, the chief bookmaker at Station Casinos. “Will there be a safety? Will the first score be a safety? Will Seattle’s defense score? Will there be a safety on the first play?” The odds on those bets ranged from long to longer, and so 12 seconds into Super Bowl XLVIII, most of Las Vegas’s top sports books were several hundred thousand dollars in the hole. (No tears, please: the surprisingly lopsided Seattle win ultimately made the game one of the books’ most profitable Super Bowls in memory.)

Inside exclusive club of coaches who led two different teams to Super Bowl

That high snap also marked the third straight Super Bowl in which a safety occurred, a run that has left a lingering impact on the extended annual byplay among the books, the pro bettors and the public leading up to the big game. Betting on a safety has become one of the most popular big game wagers on the Strip, but, says Frank B., a professional sports bettor in Vegas: “If you had any sense, you had to bet against a safety last year. Sharps were hustling around betting ‘there won’t be a safety’ all over the place. I know one guy who got that at -375! Do you realize how ridiculously cheap that is?”

Minus-375 means that in betting there won’t be a safety in the game, you put down $375 to win $100. To put it another way, those odds are saying that a safety will occur once every 4.75 games. That’s statistically absurd. Safeties happen about once every 16 or 17 NFL games. True statistical odds for no safety occurring would have been more like -1,500.

The rub is that the public—the squares, the masses, Las Vegas’s giant swarm of non-professional bettors—likes to wager on things where you put down less money to win more, and they prefer to bet that something will happen rather than that something won’t. It’s more fun that way. The odds of a safety occurring in Super Bowl XLVIII, for example, went off at around +550, meaning those who bet $100 won $550. Statistically, the odds should have been even better, but still, the squares ate it up.

Sharps, the pros, don’t look at things the way squares do. They simply want the best value for their money. All the square money that comes in heavy on the “yes” side pushes the line in the other, exploitable direction. “Safety odds are pure sharp versus square,” says Frank B. “But a lot of other factors go into finding value in Super Bowl bets. It’s like an ecosystem.” It is also by far the most profitable event of the year for the Vegas sports books and the Vegas wiseguys, both sides reaping the benefits of the most extravagantly active time in Vegas. On Super Bowl weekend, everyone is in town, everyone is betting and everyone is betting on everything.

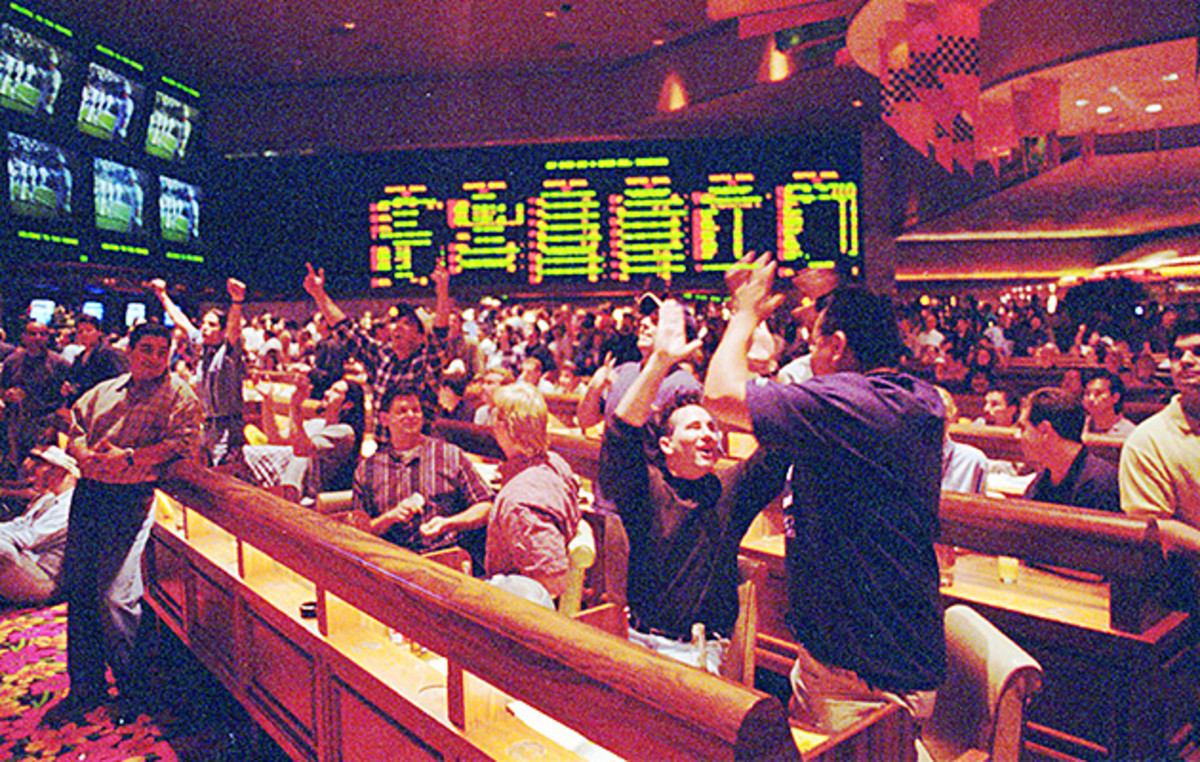

Wherever you set up to watch the Super Bowl in Las Vegas—in the bright red pews at the Venetian, perhaps, or in a leather armchair at the Bellagio; nestled among the roped-off couches at the Wynn, maybe, or standing by the bar at the Westgate—there is always a moment of relative quiet and anticipation, a gentle tension, at about 3:25 p.m. PT. Up on so many screens at so many sports books, a referee stands at midfield, the respective team captains on either side of him, a commemorative coin resting on the back of his thumb. And then that coin is in the air. And then it falls to earth.

“Heads!” the referee calls out, or just as likely, “Tails!”

“At that moment this huge roar goes up,” says Jay Rood, who runs the book at the Mirage. “Half the people have won their bet on the coin toss, half the people have lost, and the greatest day of the year in this town is officially underway.”

Total wagering on the coin flip may only account for what Rood calls “a grain of salt in a salt shaker” in the context of the $115 million-plus that constitutes Las Vegas’s typical Super Bowl handle (record: $119.4 million in 2014) but that annual rumble through the Strip underscores the spirit of the day. The coin flip is the first Vegas Super Bowl bet settled each year. The first settled, but certainly not the first made.

“We like to say the action on the Super Bowl starts after the AFC and NFC Championship Games two weeks earlier,” says Anthony Curtis, who runs the Las Vegas Advisor website, an au courant guide to the city’s best, and best-priced, seductions. “The minute that game ends, or even before, you hear guys at the bars at the sports books saying things like, ‘What’ll you give me on the point spread? I’m saying it’ll be 2 1/2.’ They’re betting what the betting line will be!”

Inspired by his late father, John Parry officiated Super Bowl XLVI perfectly

Super Bowl Sunday—or more precisely Super Bowl weekend—is its own breed of Las Vegas party, a white tiger on the Sin City calendar. It’s not simply that hotel rooms and card tables are brimming with the 300,000 high-, low- and in-between-rollers that descend on the desert. That crush can be rivaled during March Madness, or on New Year’s Eve. But never are the incoming visitors so focused on a single sporting (read: gambling) event. On no other weekend will you walk among the blackjack tables or into one of the ubiquitous steakhouses and see as many grown men clad in NFL jerseys as there are clad in polyester suits.

“We go out to blow off steam, to see each other the once a year,” says Tom Labetti, 43, a financial systems designer and Giants fan from New Jersey. He and a posse of friends from across the country have met in Vegas on Super Bowl weekend each year since the mid-1990s. There are plenty of others like them. “The thing I love is that everyone is a football fan that weekend,” says Labetti. “From the minute you leave the airport and start chatting with your cab driver, to being in a casino bar at 4 a.m. on Saturday, everybody’s talking about the game and the teams. And there’s a certain level of knowledge; people analyze the defenses or bring up lesser-known players. They care about it—and they’re looking for an edge.”

For the professional bettor, though, the search for the edge is basically done by then. Their bets are for the most part down, logged and ready to yield. “The first thing I do, on that Monday and Tuesday after the championship games, is hole up and make my own lines on every prop bet I can think of,” says Frank B., who has been at it, and earning a nice living, for two decades. “It’s a lot of work, a lot of research and analyzing, but it is really, really important. Nothing compares to the Super Bowl. All the professional guys make their own lines. So when the sports books put out their props on Wednesday or Thursday or Friday”—the timing varies from book to book—“I know the price I want on everything. That’s when I start to shop.”

Jackie Smith talks extensively about the drop that almost ruined his life

At the same time that Frank and his ilk are squirreled away examining past performances, establishing probabilities and so on, so are men like Manteris and Rood and Jay Kornegay (Westgate) and Nick Bogdanovich (William Hill) and the rest of those who work on Nevada’s 19 independent betting lines. The competition to establish the smartest and most attractive lines is a play against the wiseguys, and also against one another. “We know each other’s tendencies, but we don’t talk to each other about what propositions we’re planning to put up beforehand,” says Johnny Avello, the bookmaker at the Wynn. “I mean, where’s the fun in that? Once the props are up, word gets around about who’s doing what.”

Proposition bets are any of the innumerable wagers on outcomes other than who will actually win the game: Which team will punt more often? Will Marshawn Lynch run for more than 84 1/2 yards? Which number will be higher: Tom Brady’s completions or Tim Duncan’s total points and rebounds in the Spurs’ game later that night? Etc., etc. (Folks wanting to bet out-of-competition props such as the length of the national anthem have to wager offshore. For the record, last year Idina Menzel held her warble on the final word “brave” for 6 1/2 seconds, thus making late winners of those who took the over on the 2:01 line.)

On a regular-season football weekend, a sports book might offer 15 props on a game, max. For the Super Bowl? A book like Westgate or William Hill puts up close to 400. And in that lavish panoply of props, the pro bettor finds the opportunities of the year. They find inefficiencies in certain lines. (“If the book’s number is far off your number, you bet it,” says Frank B.) They might try to middle. (Middling, in brief: one book has a quarterback’s over/under at 274 passing yards and another has it at 262. You bet under 274 at the first book and over 262 at the other. You’re guaranteed to win one bet, and if the QB throws for between 263 and 273 yards you win both.) There are a multitude of nuances on prop bets, many ways to take advantage of bad lines and of line discrepancies, many lines to watch as they move.

No one knows exactly how many sports bettors ply their trade in Vegas these days. Six dozen? Seven score? Many use beards to place their bets. Frank, though, works Vegas on his own. During those frantic days, beginning a week and a half before Super Bowl kickoff, he and others like him scurry around, zigzagging across Las Vegas Boulevard, trying to be first in line (or close to it) when the props come up. That way Frank can bet before the odds start to sharpen and the middles disappear. “Any money coming in moves the line of course,” says Rood. “But we also look to see who is putting that money down. When it’s sharp money that effects us too.” Sports books limit Super Bowl prop bets to between $500 and $2,000, and allow bettors only two wagers at a time. Frank hopes to get down as many as 150 bets in those three or four days, to wager close to $200,000 on the game. After he’s shopped out of Vegas, he’ll ride up to Reno and “see if I can find any scraps.”

Super Bowl injuries: What it’s like to get hurt in the game of your life

“Sometimes you have to look hard to find things and other times it’s sitting there for you,” Frank says. “One of the great years was when the Falcons played the Broncos [in Super Bowl XXXIII]. I knew that the Falcons always elected to receive when they won the toss, and the Broncos always elected to defer. So you knew Atlanta would get the ball first! That gave you a huge advantage on all the bets about which player will catch the first pass, who’ll make the first sack, who’ll score first, which team will rush for the most first-quarter yards, all of that. I got down a lot of money there and made a lot. There has always been money to be made on the Super Bowl, but these prop bets have transformed everything. And they have been very good for business.”

William (The Refrigerator) Perry, the 6’ 2”, 335-pound Bears rookie who in 1985 engulfed quarterbacks as a defensive tackle, carried the ball as a goal-line fullback, brandished his gap-toothed grin in national ads and on late-night TV, and even burst into song, became commonly referred to as a modern folk hero. He was also the unwitting progenitor of the modern Super Bowl prop. As the Bears headed into Super Bowl XX against the Patriots, Manteris, then an adventurous young bookmaker at Caesars Palace, had an idea to capitalize on Fridge Fever: Let people wager on whether Perry would score a touchdown in the game.

Perry had scored three times in the regular season, but he had not touched the ball on offense for six games. Manteris put up the prop at 20-1. The bettors—sharps and squares alike—pounced, driving the price to 2-1 by game time. Then, with 3:22 left in the third quarter of what would be a 46–10 Bears rout, it was Perry, and not the great Chicago running back Walter Payton, who was given the ball at the one-yard line and charged into the end zone. Payton was angry that he was slighted. “Not as pissed as I was!” says Manteris. “We got killed on the bet … maybe a couple of hundred thousand dollars. I was sick about it, but after the game I got calls from management thanking me for the publicity we got. Plus we started something.”

How the Janet Jackson halftime show aftermath changed the Super Bowl

Today, 25% to 40% or more of a sports book’s Super Bowl handle comes from prop bets, a percentage that continues to rise, fueled by bookmaker creativity and, in the age of fantasy sports, increased bettor appetite for wagering on individual players. The beauty of the prop bet is that everybody wins: Wiseguys like Frank B. have those greater opportunities, and the books have more ways to cushion and hedge their exposure. As for visitors to Las Vegas, well, they may tend to get beaten on Super Bowl props—as on Wall Street, the general public is the source of the pros’ profit—but for many of them, the props are sweet folly.

“Beating blackjack is a mathematical function,” says Curtis. “You’re dealing with a game of dependent trials. Winning at sports is different. That’s outperforming a market. And you see that market in microcosm in all the Super Bowl action. Is it terrible that casual bettors lose a little money on props? I don’t know. They have paid for the right to be invested in the game all throughout. There’s no question prop betting has ratcheted up the excitement and attention on game day.”

At the William Hill hub, a bell goes off whenever a bet is made; in the frenzy of Super Bowl Sunday, says senior trader Adam Pullen, “it sounds like a pinball machine with mad cow disease in here.”

The lines at the sports books are already long by 7 a.m. on Super Bowl Sunday, eight and a half hours before game time. “Sports books” means every sports book in town and “long” means long. The lines extend from the betting windows and through the aisles of the pew seating, where stalwarts of the great unwashed have long since staked their game-watching spot. The line may snake out past the bar, up against the next-door California Pizza Kitchen (at the Mirage) and right to the rows of slot machines and pai gow tables.

Though there are many novice bettors on these lines—overfed tourists, older men in khaki shorts, more women than on other days—the lines tend to move quickly. Every ticket window is open on Super Bowl Sunday; no one gets the day off. That’s true in the trading hubs too, the carpeted back rooms where on rows of computers each bet placed at the book is officially traded and approved. At the William Hill hub, a bell goes off whenever a bet is made; in the frenzy of Super Bowl Sunday, says senior trader Adam Pullen, “it sounds like a pinball machine with mad cow disease in here.”

The Disappearing Man: The Raider who went missing before Super Bowl

The lines stay thick through the morning and into the afternoon until about 40 minutes before game time, when there’s a gradual clearing as everyone disperses to get to their spot for the coin toss. Maybe they go to a banquet room buffet enlivened by the presence of cheerleaders, or to a private hotel-suite soiree, or to a sports bar where the screen’s as big as a barn side and the shrimp spears come free with admission. “The best parties of the year are that day,” says Curtis, breaking it down. “Some places you pay $100 to get in, but you also get your name in a $100 box”—the betting grid in which players win depending on final score—“So you’re already breakeven. There was a bar last year where it cost $100 to get in and the box you were in was worth $75. So you’re minus $25. But then drinks were free! Top shelf drinks, too, not just draft beer. Also a free buffet and some swag. The whole thing had about a $170 value for $100!”

Whatever figuring you do around Super Bowl revenue, this much is inevitable: The books always win. Pretty much. Malcolm Butler’s late interception in Super Bowl XLIX, which ensured that the game finished 28–24 Patriots, rather than the potential 31–28 Seahawks win, “was a $2 million swing for us … the wrong way,” says Avello. “I saw the interception. I felt sick to my stomach. I put my head down and started working on a basketball bet for the next day.”

Along with iconic Vegas happenings like that first-play Seattle safety, or James Harrison’s 100-yard interception return for the Steelers at the end of the first half of Super Bowl XLIII vs. Arizona—another rare outcome that cashed in a host of related long-odd prop bets—small victories and small defeats occur on virtually every Super Bowl play. Someone stood and cheered on the Strip last year when Patriots receiver Julian Edelman made his eighth catch (over/under was seven), and when linebacker Jamie Collins was in on his eighth tackle, and when Russell Wilson completed a pass for more than 33 1/2 yards.

“Back at the Tampa Bay-Oakland game [Super Bowl XXXVII],we were at a party with a big screen, banquet seating,” says Labetti. “There were people at our table we didn’t know; it’s always like that, you make friends for three hours. This one guy, though, was a real prick from L.A. He was on his phone all game, talking about his different bets. He was heavy into Oakland, but I was heavy into Tampa Bay, and I let him know it. The way that game went [final score: Bucs 48, Raiders 21], I had a great day, and that guy just left the table. That was fun. Also fun was when Scotty jumped onto the table last year.”

Spontaneous eruptions of joy (as well as anguished collapses) are commonplace on this day in Vegas. Scott Desgrosseilliers, a 43-year-old married man from outside Boston and a veteran of Labetti’s crew, had put an atypically large bet on his Patriots to win Super Bowl XLIX. The books groaned at Butler’s interception; Desgrosseilliers leaped. “It was crazy—I actually landed on the table, started kicking over drinks and throwing food around. I’m still not sure what got into me.”

When college all-stars faced off against reigning Super Bowl champs

“You’ve been out there since Thursday night, gambling, and you’re strung out on scotch and Red Bull and whatever else,” Desgrosseilliers goes on. “So, yes, some things happen.” He recalls a few years ago when one group regular had a very profitable Super Bowl, and then found himself in a strip club early on Monday morning. Realizing his chances to get to work the next day in Florida were shot, he phoned his boss. “He called the boss’s cell phone. At 3 a.m. With strip club music in the background,” Desgrosseilliers says. “He said he was ‘sick’ and couldn’t come in. I don’t think he works there anymore.”

The party ends, but the lines at the sports book are long again on that Monday morning as the visiting bettors come to cash their tickets before flying home. The sharps sleep in that day, and the bookmakers feel like “zombies” (Avello) or “ready for a padded cell” (Manteris). Still, most everyone—wiseguy, bookie, square—agree: There’s no place they’d rather be for the big game. “Super Bowl Sunday in Las Vegas?” says Rood. “That’s a nice proposition.”