Dr. Z and the Legend of the Greatest Mock Draft Ever

A version of this story appears in the April 22-29, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

Paul Zimmerman fretted about any perceived danger headed for his mock draft once it was finished.

The legendary Sports Illustrated football writer, known as much for his bluntness as for his revolutionary insights into the technical aspects of the game, agonized too much over the damn thing. So much so that if a colleague or source called in the moments when he was finalizing the piece before filing it to the magazine (which would go to press the Monday preceding the draft) he would bristle, viewing the new information as an asteroid headed toward the glass house he’d just built. It wasn’t that more information was bad. Zimmerman loved the sleuthing involved in guessing which team would draft which player, a process typically cloaked in secrecy and subterfuge. It was just daunting to consider the possibility that all the pieces he’d just put together would have to be rearranged again.

That concept of fragility haunted many of the great mock drafters of their day, especially Zimmerman, who claimed to do one of the first ever mocks while working for The New York Post in 1971. The idea that you could spend all of January, February and March making phone calls to sources from every NFL team in an effort to put together the most comprehensive draft preview in the industry, only to have been misled, misdirected or flat-out lied to because a team wanted certain information put out there in order to influence its opponents, was both intoxicating and infuriating.

And that doesn’t even include all the other ancillary reasons a pick might change at the last minute—like in 2000, when Zimmerman was putting the finishing touches on a mock that was so startlingly accurate it would be mentioned by a eulogist at a memorial service for Dr. Z after he passed away in November 2018 at the age of 86.

In 2000, Zimmerman had correctly identified that Washington was going to take Penn State linebacker LaVar Arrington with the No. 2 overall pick and Alabama tackle Chris Samuels with the No. 3 pick (the team held both thanks to a pair of trades). But today the team’s former head of personnel, Vinny Cerato, recalls that looking back, he was privately tinkering with the idea of flipping the picks, taking Samuels second and Arrington third.

The reason?

“LaVar’s agent was kind of being a jerk,” says Cerrato. “So we were going to take Chris Samuels ahead of him just to make LaVar easier to sign.”

Cerrato didn’t go through with the plan. That meant that editors at SI, who were accustomed to Zimmerman’s day-after calls lamenting missed picks, bum sources and the nearing end of his ability to trust anyone anymore, were spared an epic rant. And the football community was also left with one of the last great examples of how a mock was done.

The landscape has changed since the golden age of the deeply reported mock draft, the purview of a handful of well-connected football writers. Now, with the manic intensification of fan interest in the draft, mocks proliferate like newly hatched spiderlings, with everyone from tapped-in experts to the proverbial kid in his mom’s basement making forecasts (and hoping to capture internet eyeballs). Back when Zimmerman did it, along with such colleagues as Rick Gosselin from the Dallas Morning News (who did his final one in 2011), the mock draft was a thing of beauty; a mosaic constructed from hundreds and hundreds of conversations.

“Dr. Z, he was the guy people looked to for years,” Gosselin says. “You’d always look to Paul because you knew he had the best sources.”

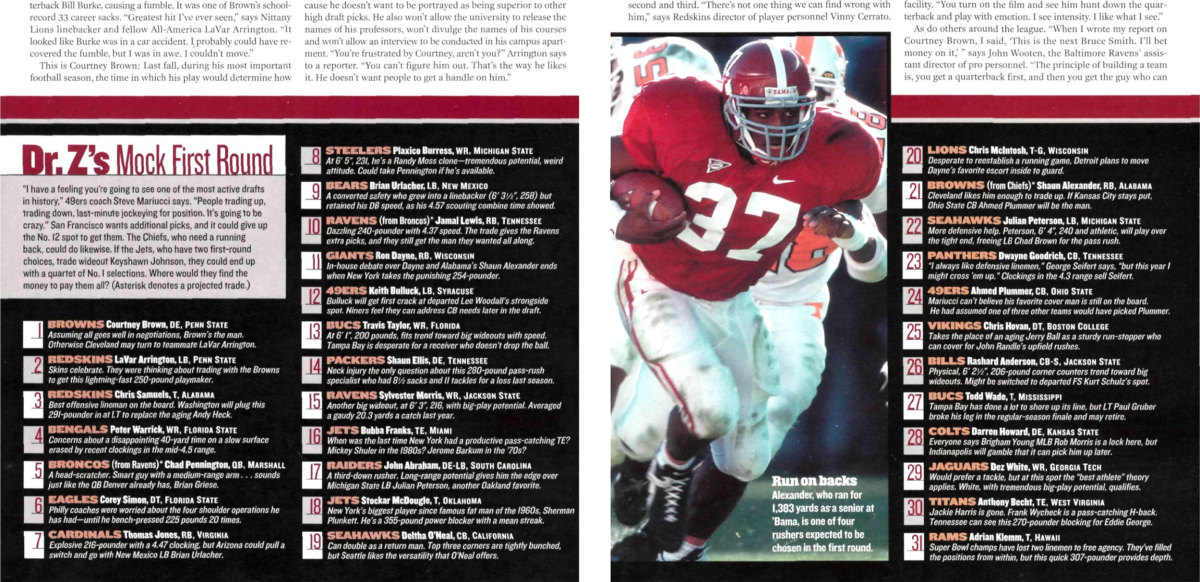

Zimmerman’s 2000 mock draft appeared in the April 17 issue of SI, deep in a magazine filled with glossy photos of the new Chrysler P.T. Cruiser, ads for Camel cigarettes and a feature on three of baseball’s young stars—Johnny Damon, Carlos Beltran and Jermaine Dye. He nailed an astounding nine of the first 11 picks in that mock, and had a 10th player-team match in the first 11 correct but in the wrong spot. What tripped him up was a projected trade at No. 5, where Dr. Z had the Broncos moving up from 10 with the Ravens to take quarterback Chad Penningon. Instead, the Ravens stayed put at 5 and selected running back Jamal Lewis. Zimmerman actually got Lewis-to-the-Ravens correct but had him going to Baltimore at 10 instead of 5.

Remarkably, though he missed the details, Zimmerman also was right about a Broncos-Ravens first-round trade. Baltimore held the No. 15 pick as well as No. 5, and on April 12—three days before the draft, but two days afterthe SI issue with Zimmerman’s mock went to press—the Ravens dealt No. 15 and No. 45 to Denver to move up to 10, where (in real life) they took receiver Travis Taylor.

In addition to nine in the first 11—including the Giants snagging Wisconsin running back Ron Dayne at 11 despite, as Zim noted, a push from some coaches for another running back, Alabama’s Shaun Alexander—he also correctly mocked cornerback Ahmed Plummer to the 49ers at 24 and defensive tackle Chris Hovan to the Vikings at 25. The total: 11 “direct hits” (the pick, the team and the player) out of 31, including eight in the first 10.

For perspective, ESPN’s Todd McShay, rated one of the most accurate mock drafters in 2018, had five of his first 10 selections as “direct hits” (though he missed at No. 1). The most accurate draft of 2018, as scored by a tracking site called The Huddle Report had just two “direct hits” in the top 10 (you can also earn points for matching the team and player, the player and the draft slot and other qualifiers).

“It’s beyond pretty good—it’s phenomenal,” ESPN draft analyst Mel Kiper says of a performance like Dr. Z’s in 2000. “You’ll do a mock and people will say ‘Oh, yeah, what an idiot, he only had six direct hits in the first round.’ There’s nothing wrong about five or six!”

A spin around the top of the 2000 draft provided a window into both the depth of Zimmerman’s sources and the respect he’d cultivated around the league. Chris Palmer, then the head coach of the Browns, grew up in Brewster, N.Y., worshipping the sportswriters of his time.

“Dr. Z was old school, he was a nuts-and-bolts football guy,” Palmer says. “And his friends were old school football. You knew when you were talking to him you were talking to one of the lords of football.”

Then there was Cerrato. He came of age in a 49ers organization that would tack up as many as eight mock drafts in their war room and update them constantly as the latest ones were published, a process that made small-time celebrities out of the writers who made a living forecasting the picks. (“George Seifert used to love that stuff,” he says.) Cerrato says long-time assistant coach Ray Rhodes, who would later head the Packers and Eagles, was so attached to Kiper’s draft guide that staffmates would call him “Mel Rhodes.”

Even Brian Billick, the coach of the Ravens, who detested mock drafts (“I mean, if you’re relying on those things, you’re going to get f----- in the end,” he says), seemed to have a respect for Zimmerman’s Rolodex. The great mock drafters of the time served as a peripheral part of Baltimore’s pre-draft strategy, which was: Obtain as much information as possible without surrendering any. Part of that intel came from noticing mock drafts by certain writers who had obvious relationships with certain agents, coaches, scouts or general managers.

The amount of intel changing hands was staggering. Gosselin says for two straight months he’d be on the phone from six in the morning until well past 1 a.m., and that’s only if a chatty personnel director didn’t catch him after a late-night meeting at the facility and keep him on the line until the early hours of the morning. Zimmerman had anchors on all 32 teams. He approached the mock like a reporter, even if his background and rise in the profession was propelled by his knowledge and hardcore analysis of the game itself.

“Whatever 180 degrees from ‘I don’t give a damn about that,’ that’s where Dr. Z was with his mock draft,” recalls Andrew Perloff, one of Zimmerman’s editors at SI. “He started talking about it in January, and he just loved playing amateur detective.”

The irony, of course, is that all of this mania helped fuel an industry that went on to devour itself whole. Now, when mock drafts can be updated repeatedly and instantly online, stats and clips can be had with a click, GMs can be texted or emailed, and even the most respected draftniks doing multiple mocks, the notion of posting mocks on a war-room wall or making endless calls from a Rolodex seems woefully outdated. Cerrato hosts a radio show in Baltimore now, and he recently had a guest from a prominent website who had just completed his 28th mock draft of the 2018-2019 season. Twenty-eighth.

If Cerrato were still in a front office today, it probably wouldn’t matter much to anyone in the mock draft industry if he switched the order of his picks. Everyone doing a mock draft would have produced so many versions that they were bound to have one with the correct order. The days of Dr. Z’s singular mosaic, coddled and fretted over for months, are no more.

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.