T.J. Watt and the Art of the Takeaway

T.J. Watt hesitates. Not on the football field—his job does not allow for that—but when asked to explain how he’s made a game-changing play into his signature skill. He decides the only way is to take you along with him as he comes charging off the line of scrimmage, the quarterback in his sight, homing in on what’s become the object of his every pursuit.

“When I am coming around the corner, typically, if you get there soon enough, the ball is still in both his hands,” Watt begins. “And within a split second, that ball can come up to their shoulder for the throwing motion . . .”

This is what Watt’s defensive coordinator, Keith Butler, calls “his science.” The sight of No. 90, coming off the left edge of the Steelers’ defense, has fast become an unwelcome one for opponents. Over the last two seasons, no NFL player has been more successful than Watt—this Watt—at stripping opposing players, often quarterbacks, of the football.

Each snap is over within a matter of seconds, and the window of time to swipe, punch or rustle free the football is a mere fraction of that. Making a play under these circumstances requires being able to see real time almost as a series of freeze frames, and then react to each one. This is what Watt is trying to describe. If he sees the quarterback still holding the ball with two hands at his chest, patting it, he’ll go for the strip with his right hand and the tackle with his left arm. The split second he brings it back to throw, Watt must switch: strip with the left, tackle with the right. “If you watch film, I have missed plenty of times,” Watt continues. “Because your brain sees the ball, but by the time you swipe there . . .”

Consider those misses valuable data points in his ongoing research. In an era skewed heavily toward high-scoring football, taking the ball away is more valuable—and rarer—than ever. With scientific precision, Watt has elevated this into an art form.

* * *

In Pittsburgh, head coach Mike Tomlin likes to refer to the ball as his team’s “hopes and dreams.” It’s cheesy, but endearingly so. The offense carries those hopes and dreams; the defense is trying to get them back. And 14 times in the last two seasons, then, Watt literally ripped away an opponent’s hopes and dreams.

Tom Coughlin used to tell his Giants teams before every game that losing this turnover battle was the quickest way to defeat, and that’s a message most coaches echo today. It’s impossible to go a week in the NFL without hearing a coach preaching the importance of the turnover battle. While correlation is not the same thing as causation (over the past 10 seasons, more than twice as many turnovers have been committed by a team trailing than a team leading), players and coaches constantly hear a version of these statistics: Teams with a positive turnover margin have won nearly 78% percent of games in the past decade. The winning percentages spike to the high 80s for a turnover margin of plus-two or better, and nearly 95 if a team is plus-three or more.

When Dan Orlovsky, now an ESPN analyst, was Matthew Stafford’s backup in Detroit in 2015, the team started 1–7, with a turnover margin of minus-nine. He remembers then Lions coach Jim Caldwell coming into the team meeting and reading a similar grid of win-percentage stats. The message sank in. The team won six of its final eight games, giving the ball away just four times and finishing that stretch with a plus-four margin. “The only thing that changed was turnovers,” Orlovsky says. “That was the first time in my life where I actually saw it have tremendous impact on the wins and losses.”

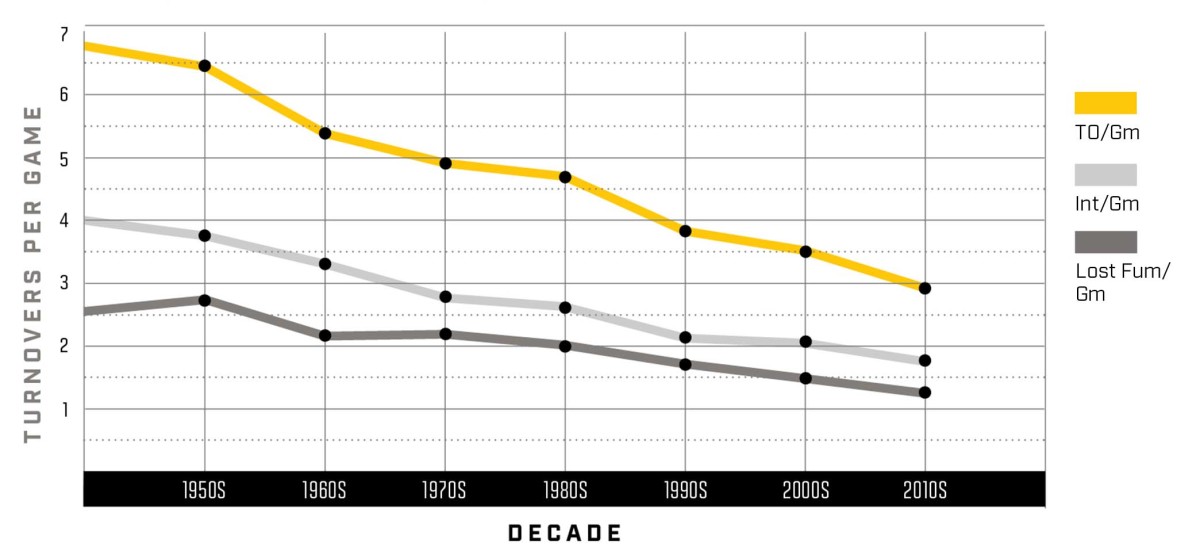

With offenses emphasizing taking care of the ball, takeaways are becoming scarcer. Both forced fumbles and interceptions have been on a steady decline through NFL history. There are just six seasons that featured an average of fewer than three takeaways per game—the six most recent seasons. At the high-water mark, in the late 1940s and early ’50s, the average was more than seven per game.

Dick (Night Train) Lane’s 14 interceptions in 1952 still hold up as the single-season record; no one has reached 10 since 2007. Paul Krause’s career record of 81 interceptions is nowhere near being threatened; Richard Sherman, the leader among active players and in his 10th season, has 35. The AFL’s San Diego Chargers had 66 takeaways over 14 games in 1961, the most in a single NFL or AFL season. The Steelers had 38 in 2019, the most by any NFL team over the past four seasons.

“It’s a different era,” says reigning Defensive Player of the Year Stephon Gilmore, whose six interceptions for the Patriots last year tied for the league lead. “Back in the day, those guys could jam all the way downfield. They got away with a lot more things than we can now.”

Steelers Hall of Fame defensive back Rod Woodson recalls Dick LeBeau, the legendary defensive coach who also played cornerback in the NFL from 1959 to ’72, telling him how in his day he could cut the receiver at the line of scrimmage—just dive at his knees. It’s impossible not to acknowledge the impact of rule changes: The NFL’s interception rate plunged in 1979, the year after the league instituted the five-yard chuck rule and gave offensive linemen more allowances while pass blocking. In more recent years, new efforts to restrict contact, such as defenseless receiver protections and more stringent roughing-the-passer provisions, have eliminated some of the dangerous blows that often jarred the ball loose.

But the full picture requires a wider lens. “Everything about the game,” says Hall of Fame quarterback Kurt Warner, “lends itself to fewer turnovers.”

More than ever, offensive schemes are designed to make quarterbacks’ jobs easier, and the transformation has made it more difficult for defenses to take the ball away. Orlovsky points to the role the Patriots invented in the 2010s for Rob Gronkowski, the versatile tight end who could be moved around the formation as a coverage tell, thereby clarifying the quarterback’s progression and allowing him to get the ball out faster—before a pass rusher can get his hands on him or the ball—and to the right place. The combination of rules limiting contact and pass concepts that take advantage of the full width of the field help receivers get more open. On top of that, the advent of the run-pass option has given quarterbacks the ability to not just audible presnap, but get into a better play postsnap, too.

With NFL decision-makers beginning to embrace the mobility of quarterbacks instead of maligning it, passers use that part of their skill set to make their own jobs easier. “A guy like me, when things start to collapse, my only way to protect myself is to throw the football,” says Warner. “I’ve gotta throw it into a tight window, or try to make a throw with the guy hanging all over me or getting ready to hit me.”

These are the challenges for defenses, but they don’t change the objective. If you’re going to go after your team’s hopes and dreams, you better find ways to do so.

* * *

Watt has been seen: wrestling the ball away from Ryan Fitzpatrick after beating Miami’s right tackle on a swim move. Swatting Jared Goff’s forearm with his left hand as the Rams QB wound to throw. On a single play, lining up over Bills slot receiver Cole Beasley, chasing down Devin Singletary after a handoff, then punching the ball out from behind with a closed right fist. On opening night of his fourth NFL season, on the Steelers’ ninth defensive snap of the game, Watt again wielded that left-handed swat, causing Giants QB Daniel Jones to throw with an empty hand—though officials ruled it an incomplete pass.

Butler has been coaching with the Steelers since 2003, including a decade spent as the linebackers coach for stars like James Harrison, Joey Porter and LaMarr Woodley. “All those guys were good pass rushers,” Butler says. “T.J.’s probably the best one at getting the ball out, though.”

The Giants’ Osi Umenyiora set the league’s single-season forced fumble record in 2010 (with 10) by surprising quarterbacks from the blind side, the right side of the defensive formation. (But never Tom Brady, who had another weapon that defenders have to find an answer for: intuition. “He would shrug his shoulders forward,” Umenyiora says. “There was no way he could have seen you coming, but it’s almost like he felt it.”)

Many of the league’s best strip-sack artists (including Robert Mathis and Cliff Avril) rushed from the left, however. And Watt took off in his second season, 2018, when Tomlin made the decision to have Watt and Bud Dupree, another talented young pass rusher, flip sides. As a rookie Watt had lined up almost exclusively on the right, but, says Steelers defensive line coach Karl Dunbar, Tomlin believed Watt’s athleticism would make him a mismatch against the league’s right tackles, who are more often better run blockers and less nimble in pass protection.

The biggest change for the former first-round pick was a whole new vista. “I didn’t realize rushing from the left how much visualization you have,” Watt says. “I can see the quarterback’s eyes a lot more so I can bat passes down. I can see what kind of drop he’s taking. And I can always see the football when I’m rushing the quarterback, whereas on the right side, you can’t really see it at all.”

In his new position, Watt became the first Steelers player with multiple seasons of 13 sacks or more. Over the past two seasons he had more forced fumbles (14) than anyone in football, and was tied for first in strip sacks (10, with Arizona’s Chandler Jones) during that span, all of them coming when lined up on the left. His sole forced fumble as a rookie, a game-clinching strip sack of Ravens QB Joe Flacco, also came rushing from the left side, a rare instance that season.

Something else changed in Watt’s second season: He became confident enough in the Steelers’ defense to start taking more chances. As a rookie, his priority was to not mess up—just make the tackle. Now, he goes for the ball and the tackle.

The 25-year-old Watt began his college career at Wisconsin as a tight end—he switched to defense just five years ago—so he used his ballcarrier’s perspective as he looked for potential advantages. “As I watched more and more film, I could see how vulnerable players are and how careless they are with carrying the football,” he says. Quarterbacks who hold the ball in one hand while in the pocket or let the ball drift from their chest as they move around are easy targets. Watt also studied running backs, who are prime for a left-sided defender when they have the ball in their right arm.

He discovered that when ballcarriers make cuts, their elbows will often drift away from their bodies, creating a little seam where the ball can squirt out. He began working on the timing of this punch every chance he could in practice, often to the chagrin of his offensive teammates. “Our running backs go crazy, because sometimes he punches them and hits them a little bit too low,” Dunbar says, before spelling out the painful truth: “He finds some other balls.” (Sam Darnold of the Jets, the recipient of an off-target Watt punch that still resulted in a strip sack last season, can relate.)

In two other instances last year, Watt’s pugilism paid off: While chasing down Seattle’s Chris Carson in Week 2 and Buffalo’s Singletary in Week 15, Watt balled up his right hand in a fist as he approached for the tackle. With one smooth punch-wrap motion, he brought down both the back and the ball.

Of course, there have been swings and misses. There was the play against Cleveland last December, with the Browns just outside the red zone, when he came around the edge completely unblocked. Watt wrapped both arms around Baker Mayfield, but the QB was still able to get off a pass before Watt could bring him down. “If I would have just extended my arm and gone for the ball, I would have gotten a [strip] sack for sure,” Watt says.

And in this year’s opener, he says he mistimed his swat at Jones, hitting his arm instead of the football. “Still should have been a sack fumble,” he says with a grin, “but they didn’t count it like that.”

When Watt rewatches these plays, he looks for what he could have done differently—maybe punching from a different angle or pulling on the ball to finish. But sometimes his coaches will point out an opposing QB moving the ball to his left hand to get it away from him, proof his opponents have done their film study, too.

* * *

The Steelers’ pregame scouting reports include an analysis of how quickly the opposing quarterback gets rid of the ball, broken down by down and distance, offensive formation and the coverage they are facing. The grid of numbers—in the modern game, generally all under three seconds—reinforces how little time the pass rush has to get to the ball. It also illustrates how the defensive front and the back end must work together in a symbiotic relationship that fuels the quest for takeaways.

“We have a lot of four-man rushes on third down,” Butler explains. “And as a consequence, when you’re rushing [only] four you’ve got a chance to give different looks in your secondary and make the quarterback read those different looks.”

The Steelers had 20 interceptions last season, second-most in the league. There are picks that come out of inaccurate throws or deflections, both of which can be forced by pressure. But the majority of the Steelers’ interception plays—picks as well as dropped interceptions—came through coverage disguises. The Steelers’ combinatorics on the back end were further enhanced last Sept. 16, the day they traded for Minkah Fitzpatrick.

“When I first got him, I was thinking, Man, we gave up a No. 1 draft choice?” says Butler. “And then all of a sudden it was, Man, we gave it up for good reason. If it was up to me, I’d do it again, because he’s been that valuable to us.”

Fitzpatrick was the missing piece on the back end of the Steelers’ defense. Playing the deep safety role, he brought both the athleticism and smarts to help his unit disguise its coverages—showing the offense a look presnap before morphing into a different one. Defensive players must be able to hold the disguise as long as possible yet still get to their coverage responsibilities. It’s a way to actively scheme takeaways, sowing confusion for the quarterback.

Factors like the mobility of quarterbacks and offensive concepts like RPOs are spurring defenses to play more man-to-man coverage, which can make it more difficult to snag interceptions. The aforementioned rule changes don’t exactly facilitate tight bump-and-run coverage. And playing man means defenders often have to turn their backs to the quarterback as they chase their assignment—whereas in zone, defenders can watch the quarterback and wait to break on the ball.

However, the league’s best man-to-man defender uses that perception to his advantage. “[Man coverage] gives you more chances to make plays, because the quarterback feels you can’t see him,” says Gilmore, whose Patriots led the league in interceptions last year (25).

Gilmore’s first pick this season, in New England’s Week 1 win over the Dolphins, left former Cowboys QB Tony Romo bewildered on the CBS broadcast. “He’s guarding man-to-man, but he’s watching the quarterback,” Romo gushed. “That’s a hard thing to do.” But as Gilmore explains it, the play came down to trusting his technique and his film preparation. It was a third-down play, so Gilmore was not going to go past the first-down marker. He played outside leverage, because of receiver Preston Williams’s tight split (meaning the Miami wideout lined up close to the formation). He knew that he would be able to beat the bigger-framed receiver to his spot. When Williams slipped, Gilmore was watching quarterback Ryan Fitzpatrick, poised to make the interception.

“I feel like some guys, they worry too much about what the outcome is going to be,” Gilmore says, “instead of being confident and playing the situation.”

One day later, he watched as another player made an interception rooted in this same kind of confidence and preparation. On a second-quarter play against the Giants, Watt realized he wouldn’t have time to get to Jones. But he noticed the QB looking in his direction, so he abandoned his rush and dropped into coverage; when Jones tried to throw a quick out, Watt launched his 252-pound frame into the air to snag the ball.

“You don’t see those plays made by just any defensive lineman,” Gilmore says. “I don’t know what makes him great. [But] I’m pretty sure he has his niche, his anticipation, his preparation.”

* * *

There’s an argument to be made that the strip sack is the most impactful of all defensive plays. An interception is often akin to a punt, the change of possession coming downfield. But a strip sack occurs behind the line of scrimmage, flipping the field even without a big return.

“It’s something that I felt I could bring to my game,” Watt says, “and make into my own.”

His ability to do it so well and so soon has meant reframing aspirations. Dunbar, Watt’s position coach, has given his pupil a goal of 30 sacks (if it seems unattainable, that’s the point). Watt’s older brother, Texans defensive lineman J.J., said on the eve of this season that he’ll see T.J. as his peer once he, too, has been awarded three Defensive Player of the Year Awards. This is fair, T.J. says, but he adds: “I’d rather have a Super Bowl ring, to be honest with you. That would shut him up pretty quickly.”

But it’s time to narrow the focus again. Achieving those goals will depend on what happens in those seconds between the snap and the throw; Watt’s trying to pick the right moment—the perfect freeze frame—to swipe, the Steelers’ hopes and dreams in the palm of his hand.

Additional reporting by Andrew Kristy