Those Old, Hard-Luck Chiefs Know: This Team Is Different

KANSAS CITY — On the same week that the Chiefs—the bad-mojo, bad-calls and bad-plays-in-the-postseason-for-most-of-half-a-century Chiefs—prepared to host a third consecutive AFC championship, two old friends who lived that painful history caught up over text message. There were new developments to consider, a pattern being overcome.

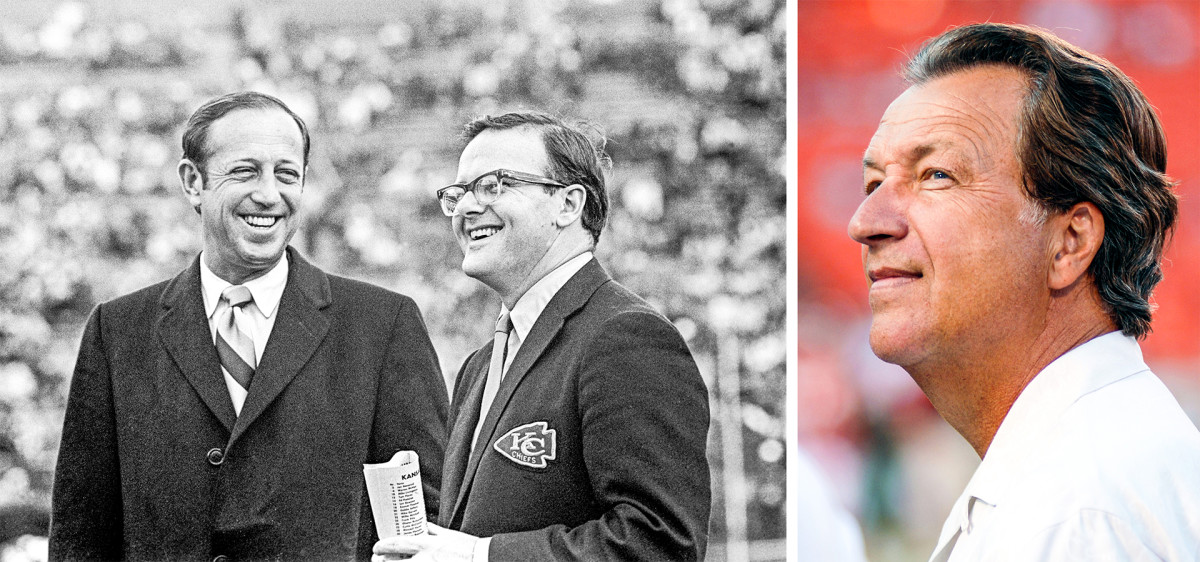

Carl Peterson, the franchise’s longtime general manager (1989–2008), the architect of playoff team after playoff team, started the conversation by reaching out to owner Clark Hunt. Peterson referenced last year’s victory on the same weekend, the one that brought the Lamar Hunt Trophy—named after the team’s founder and Clark’s father, given annually to the AFC champion—back home. “You guys all worked too hard last year to finally get the trophy to Arrowhead Stadium,” Peterson typed. “Let’s not give it up too quickly.”

Hunt agreed, saying he hoped to avenge one particular loss on this particular stage, a defeat handed down by the same opponent the Chiefs would face on Sunday: the Bills. The teams played that game in Jan. 1994, in Buffalo, where the Chiefs arrived a few days early, due to an impending snowstorm. Cars driving by the Chiefs' hotel wore white sheets on roofs like a high fade. Trains left town, their cars packed to the brim with excess snow. The Chiefs would lose that conference championship, 30–13, in Joe Montana’s penultimate season in KC, his arrival having bummed out a young fan named Tom Brady, who lived near San Francisco and rooted for the 49ers.

The hard part happened next. In the following 22 seasons, Kansas City won division titles, registered three 13-win seasons and made seven return trips to the postseason, sometimes with a first-round bye and home field advantage. The franchise, which featured NFL luminaries like Montana, Derrick Thomas and Tony Gonzalez, still didn’t win another playoff game until 2015. “You don’t envision that,” Peterson says, all but spitting on the sentence.

Lamar Hunt would come to call this improbable series of events by a simple phrase: Buzzard’s Luck. Meaning, Peterson says, that footballs are oddly shaped and bounce funny, that players make mistakes, that referees are human.

“That’s football,” he says, moving on.

Eventually, Hunt hired Andy Reid, a coach with a Hall of Fame résumé and similar (if not deserved) reputation. Reid had guided the Eagles for 14 seasons, winning six division titles and reaching the conference title game five times (while never winning the Super Bowl before last year).

Along the way, a superagent named Leigh Steinberg, who represented Deron Cherry (K.C. Ring of Honor), Thomas (same) and Gonzalez (ditto), along with Pro Bowl kicker Nick Lowery, often told Lamar Hunt the same thing. Steinberg considered Lamar a visionary, a man responsible for how big—and profitable—the NFL had become. But he lacked a central element to postseason success. “The only way you’re ever going to solve this is by taking a franchise quarterback and developing him,” Steinberg says he told Hunt.

Fast forward to 2021, past the January 2019 overtime home loss to Brady and the Patriots, past the Lamar Hunt Trophy returning home, past the Chiefs’ first title in 50 years and a pandemic and world thrown into chaos. What’s clear about this Kansas City team is its dynastic aspirations, which were formed not by ignoring the past but by confronting that history directly—a path that led directly to Brady, in a Montana-second-team cameo with Tampa Bay, and Super Bowl LV.

* * *

Derrick Johnson, the franchise’s four-time Pro Bowl linebacker, watched the Super Bowl last February at home. He didn’t want to jinx the Chiefs' chances against the 49ers. He watched, as San Francisco pulled ahead, before a franchise quarterback, the franchise quarterback, Patrick Mahomes, erased a 20–10 deficit in just under nine minutes. Soon after the Kansas City triumph, Johnson received a text message from Reid, telling the linebacker that he helped set the standard that carried through until now.

In informal conversations with former teammates and current players, Johnson always emphasized the same points. Like: Don’t take a run like that for granted. And: So much could go wrong, in any given season. He knew that as well as anyone, after a K.C. career that spanned 13 seasons and netted only one playoff victory—a wild-card win at that. “You never know when you might be back,” he told them.

Johnson also watched this season with great interest, as 4–0 became 14–1 and the Chiefs marched toward NFL supremacy. Part of him lamented retiring after the ’18 season, spent in Oakland. What timing! These Chiefs made the kicks, seized the bounces, won close games. They had …. good fortune? Or, at least, Mahomes. The combination netted eight games won by a touchdown or less.

Lowery, the kicker, watched the season unspool with similar interest, wondering, like most of Chiefs Kingdom, when the universe would resume torturing the football team in Kansas City. He remembered, of course, the 52-yard potential game-winner he missed in the playoffs in January 1991, despite having made every kick (24) for almost three months. There was a holding penalty to bring back a long run before the kick, the only one the Chiefs committed in the second half, that turned a chip shot into a much longer attempt. “Those things happen,” Lowery says.

In more recent years, Lowery spoke with Theo Epstein, the baseball GM who upended “curses” with the Red Sox and Cubs. Epstein, Lowery says, told him that he looked specifically for players who had confronted adversity and overcome whatever happened to them. Think Jason Heyward, the Chicago outfielder, who rallied his team during a Game 7 rain delay.

Lowery sees those same qualities in these Chiefs, particularly with Mahomes. It’s like, he says, trying to date the same person for years, not realizing they’re too good for you, and then one day waking up to find out that person wants to get married. “I’m just grateful,” he says.

* * *

The new Chiefs began their transformation years ago. They hired the right coach, the right general manager (Brett Veach, 2017) and constructed a solid foundation that would be amplified by the franchise quarterback they drafted the same year. This offseason, when Mahomes signed a massive contract extension (worth up to $450 million over 10 years), Veach and the quarterback’s agents built flexibility into the near term, allowing KC to extend star tight end Travis Kelce and stud defensive tackle Chris Jones. This kind of planning isn’t luck. But once complete, it sure can lead to it, along with the kinds of low-cost, high-reward signings—see Bell, Le’Veon, added in October—that became a staple of the Patriots’ extended run.

“The point is, they’re steady, they’re measured, they don’t panic,” notes Steinberg, which is a funny thing to say about a team that deploys a player among the most exciting in the history of football. But that very excitement, all the no-look passes and sidearm throws, is grounded in the foundation that’s now established. It starts there.

It helped, Lowery posits in a twist, that COVID-19 shut so much of the world. That meant these Chiefs didn’t have the usual banquet circuit following their triumph, the usual mishmash of radio shows and TV appearances and celebrity hangs. The celebration ended in early March, leaving more time for a renewed focus.

Steinberg had been right, by the way, and he wasn’t exactly far out on a limb. The elite teammates, roster depth and deepening chemistry all mattered. But nothing mattered as much as Mahomes, the franchise quarterback that Steinberg—now one of Mahomes’s agents—had told Lamar Hunt he needed. Mahomes only bolstered the steady nature of KC’s operations; he even worked out on the day the team held its Super Bowl parade.

Identifying and landing Mahomes wasn’t luck, either. But being able to trade up for him in that draft, to move in front of other franchises that coveted his services, required some good fortune. Johnson, for one, will take the break. “It was one of those things where, you’re like, we’re due,” he says. “We had great quarterbacks, but for years and years, we were searching for that guy. And we got the one who comes around every 20, 30 years. He’s that good.”

All of which raises a relevant question: What comes first? The kismet to land the right players? Or the right players making the plays that once doomed a franchise that was close but never all the way there? Good luck, Peterson says, comes from being ready, from giving a team a chance every single year. The way the Chiefs are set up, more or less.

* * *

And yet, Mahomes left the Chiefs' playoff game in the divisional round against the Browns to enter the NFL’s concussion protocol. Was this not the worst kind of Buzzard’s Luck imaginable? No, turns out. Backup Chad Henne won that game, cementing his place in a burgeoning dynasty, before Mahomes returned healthy, and bludgeoned the upstart Bills.

Asked afterward where he saw his team’s “ceiling,” Reid drifted back into coach speak. He compared winning football games to toiling on a farm, in that the work is never over. “Listen,” he said, as if talking to himself, “we got room to get better.” Mahomes? He shrugged.

That’s the thing about these Chiefs. Their franchise might be known for postseason disappointment, and their fans might have endured more than should reasonably be expected. But Mahomes? Kelce? Jones? They’re too young to really know the history, let alone be consumed by it. They won often, consistently, efficiently, making sure the only doomed teams were their opponents. They did so, Steinberg notes, without any conflicts, or leaks of conflicts, without controversy, with mindfulness of the obstacles ahead. No drama, he calls it.

“They’re a smoooooth operating dynasty at this point,” Steinberg says, before catching himself.

“I mean, they have to do it.”

“These are not the same Kansas City Chiefs,” Steinberg continues. “Understand, for Patrick Mahomes, [the history] isn’t part of his consciousness. With fans, there was an exorcism that happened last year when they actually won the Super Bowl. But again, these concepts, the players know nothing about [them].”

Like defensive end Frank Clark, another big-money signing. When asked whether he had anything to say to Brady on Sunday, he first said no, then said, “I’m gonna see his ass in the Super Bowl.”

That’s how dynasties are born, not by boasting but by the confidence and competence the Chiefs exhibit. Throw in great players, an all-time quarterback just rounding into his prime and an unstoppable offense, and things that can look like luck or better fortune aren’t really that at all.

“I don’t like the word ‘dynasty’ until somebody’s done it,” Peterson says. “And there are very, very few that have ever done it. But these guys have a chance.”