Trey Lance Is Just Different

The most extraordinary prospect in the most peculiar draft in NFL history starred in college, but for an FCS power. He won all 17 starts and then lost essentially an entire season—he has played only one game in the past 15 months. He’s mature enough to lead virtual Bible studies but not yet old enough to buy a drink, prefers audiobooks to TikTok and made up for the lack of a traditional scouting combine by scripting not one but two pro days.

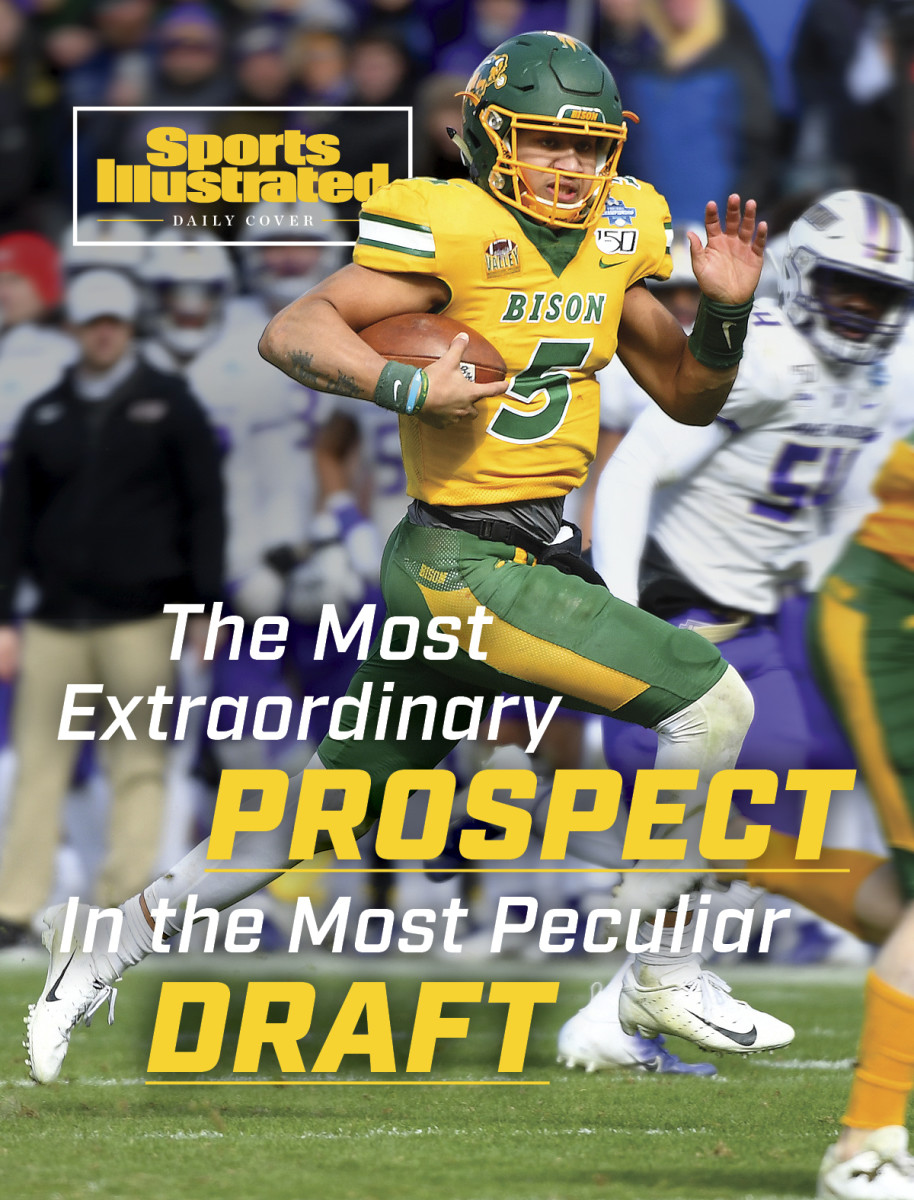

He’s Trey Lance, the North Dakota State quarterback likely to be drafted in the first round, as high as third, on Thursday. He’s confounding to some (“Talented, not sure what to make of him,” says a personnel executive for an AFC playoff team), enticing to others (“Love everything about him,” texted an NFC general manager) and fascinating to all. He’s built like a linebacker, tall (a shade under 6' 4", 226 pounds), rocket-armed, fast, versatile, tireless and smart. In 2019 he navigated the Bison to an undefeated national championship season. In 2020, he stumbled against Central Arkansas and skipped NDSU’s spring season to prep for the future.

All those factors combine to make Lance the perfect prospect for an imperfect year. It’s as if his big-time skill set and small-school background conspired with a pandemic to create a prospect singularly divisive among scouts.

Over the past two months, as Lance sought counsel from fellow Bison alum Carson Wentz, polished his mechanics with QB guru Quincy Avery, painted Air Forces Ones and rallied against social injustice, Sports Illustrated followed him along the way. Over time, a theme emerged: Lance didn’t view the circumstances surrounding this draft and his place in it as all that unusual, certainly not in the way that executives, draft pundits and keyboard warriors seemed to examine him.

Speculation swirled all spring, anyway. Lance would surely become a 49er, a Panther, a Bronco, an Eagle, a Patriot. He resembled Cam Newton, Josh Allen, Steve McNair, even Patrick Mahomes. He would be ready to start immediately his rookie season. He needed a year to develop. Experts alternately branded him as a project, a surefire starter, a gamble, a perennial star.

Rather than wade into abstract debates, Lance listened to episodes of Brandon Marshall’s podcast, devoured sermons on YouTube and listened to Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, Golf Is Not a Game of Perfect and The Inner Game of Tennis. All spoke to what really mattered to a self-described nerd: not where Lance will be drafted but rather what the team that selects him will receive in return.

In particular, the “thin-slicing” theory resonated as the draft approached. It’s grounded in the brain’s ability to find patterns in events based on “thin slices” of info, narrow windows of human experience. “We think we can control not judging people,” Lance says. “But our brains do that automatically.”

That’s, more or less, been his last six months: judgment season.

It’s late February, and early into the first conversation with Lance, it shifts to an unexpected family pillar: spreadsheets. They’re created by his father, Carlton, a football and track standout at Southwest Minnesota State. Carlton played two professional football seasons, as a cornerback in the CFL and the World League of American Football (later rebranded NFL Europe), settling on an analytical approach to sports that he would later share with to his sons, Trey and Bryce. This philosophy stemmed, in part, from one training camp practice in San Francisco, after the 49ers moved Carlton to safety and he struggled applying the lessons from installs to the field. “I froze,” he admits. “I had the ability to play but I couldn’t think.”

Rather than push the boys into football, Carlton deployed spreadsheets laden with pros and cons for major decisions. He would inform their choices, not dictate them. Still, his decision to coach at his alma mater hindered his ability to fully commit to his family. He heard other assistants lament missing children’s births and, like them, he worked 80 hours a week, fall weekends filled with games and film review, springs spent on the road recruiting. “I had an epiphany,” he says. “Oh, wow, this is poison.”

The next summer, during a vacation to a family lake cabin in Northern Minnesota, his pulse surged, dizziness descended and he told his wife, Angie, that “something isn’t right.” But after sitting down for 15 minutes, he improved, and he came to believe that this moment, something like a panic attack, was his body shedding residual coaching stress. He no longer had to worry about dozens of teenagers’ study habits, whims and complaints, instead narrowing his focus to the two who meant the most to him. He became a financial analyst.

The Lances had already moved to Marshall, a small burg of roughly 14,000 tucked into the southwest corner of Minnesota. It’s best known for the Schwan’s Company and its family of food products. Ninety miles from the nearest big city (for anyone who, generously, counts Sioux Falls) and a three-hour drive from Minneapolis, Angie’s hometown provided the family with the incubator they desired. The Lance’s children are mixed-race—Carlton is Black; Angie, white; Marshall has little diversity (86.8% white, according to the 2010 census), but also no racist incidents for the Lance family that any of them can recall. Their life was parks and pickup games, bucolic. “A bubble,” Trey calls it.

When NFL executives ask Coach Terry Bahlmann what teenagers do in the small town where he built a formidable football program, he always answers the same way: play sports. Most engage year-round, with the best male athletes flocking to Bahlmann and the Marshall High Tigers, hoping to slot into his Wing-T offense and build on the school’s 74–6 record in the 2010s.

Carlton says he first envisioned that Trey would play Division I basketball, until the staggering total of AAU games led to burnout. Carlton believed that Trey most excelled at baseball, but a growth spurt in high school made him too tall to play catcher. He decided to focus on football instead, where the Tigers’ constant bludgeoning of opponents sometimes worked against him. The team averaged 46 points his junior season and more than 50 the next year. But the sheer number of blowouts, the second halves sidelined, the run-heavy scheme and a back who scored 108 touchdowns, limited Trey’s tape. Even his mom says, “I never thought then he would play in the NFL.”

Her son showcased a high aptitude for math and science and compiled a 3.9 GPA. Ivies like Brown and Cornell recruited him, as did lower-level schools. But to Division I power brokers, Lance remained a mystery, same as with NFL czars now. In both cases, there wasn’t enough tape. Only Boise State offered—and then, only on the final day of Trey’s recruitment. Rather than view him like his favorite football player, the dual-threat Tim Tebow, they called him an athlete and told him to switch positions, his skill set so versatile that different programs reimagined him as a linebacker, safety and fullback.

Carlton created yet another spreadsheet, and, once he inputted the data, the choice to him became clear: North Dakota State. “You don’t know who these guys are,” he told Trey. NDSU played FCS football like Alabama played the major college version, and Bison coaches are beginning to develop quarterbacks like an assembly line to the NFL. Three years after Wentz went second in 2016, Easton Stick was a fifth-round pick of the Chargers and longtime Bison coach Craig Bohl helped mold Josh Allen after leaving NDSU for Wyoming. Trey resisted, clinging to his preferred destination (Minnesota), saying he wouldn’t attend a camp in Fargo. After his father coaxed him there, the staff sold the Lances on their detailed plan for Trey. Randy Hedberg took the family’s acceptance call on a recruiting trip in Montana. “It’s like when the Minnesota Twins won the World Series,” he says. “I remember exactly where I was.”

No, Lance says during a call in early March, Hedberg did not share his father’s affinity for Microsoft Excel. Like Carlton, though, he wanted to teach Lance the art of quarterback play through immersion and study rather than mandates. In Fargo, that meant a one-year apprenticeship under Stick, the signal-caller who followed Wentz from NDSU to the NFL. “People say, Oh, he didn’t start his freshman year,” Carlton says. “That was by design.”

Since 2014, Hedberg, 66, has served as either the quarterbacks coach or associate head coach of a program that has produced three NFL QBs, two of them first-rounders, should Lance go there. The Bison, meanwhile, went 85–6 in that span (not including this spring season), winning five national titles.

Hedberg prefers a positive teaching style over a screaming version and expects his starters to help pass down his philosophy. They meet before classes and after practice, make their own film cut-ups, offer input on game plans and teach concepts on Friday mornings to receivers, tight ends and running backs. In 2015, Wentz broke a bone in his right wrist, but before he went in for surgery, he stopped by the QB room to study tape with Easton. Three years later, Easton helped Lance shed both his Fruity Pebbles obsession and college defenses.

The offense they teach each other more closely resembles pro style. The Bison huddle regularly and demand their signal callers adjust protections before plays and take roughly 60 percent of their snaps under center.

Lance stepped from that gridiron internship into the starting lineup in 2019. The Bison opened against Butler, at Target Field in Minneapolis, and their new starter scored six times (four passing, two rushing), portending the year ahead. NDSU would play 16 games and win them all, national title tilt included. Lance would complete 66.9% of his passes while throwing for 2,786 yards and 28 touchdowns—he didn’t throw an interception on the season. He ran for an additional 1,100 yards and 14 scores. His yardage total set a school record, and his 287 attempts without a pick exceeded any tally at all levels of college football. He became the first FCS-level player to win the Walter Payton Award—the FCS version of the Heisman—and the Jerry Rice Award, given to the top freshman, in the same year. The Bison became the first team to win 16 games and lose none at any level since Yale’s famed 1894 squad.

In typical, understated fashion, after the title Lance reveled with his teammates on an airport runway, everyone packed in a broken-down plane for four hours. He was 19, his life changing in glorious ways. Hedberg says, “We’re celebrating, and I’m thinking, we get this guy for three more years.” He pauses. “Well, a month later, we start COVID.”

In mid-March, 48 hours before Lance’s first pro day, the quarterback admits that a scheduled workout of 66 throws constitutes far more than a simple audition. “My Super Bowl,” he calls it, and he knows exactly why.

When the pandemic forced decisions across sports—on when to resume and how—the football power in Fargo went hunting for games. Hedberg says NDSU wanted to play at least three times last fall, the max allowed at the FCS level, where programs were allowed to play eight more games in the spring. But geography and dominance limited the potential opponent pool for NDSU, and when most teams backed out or shut down, that left only Central Arkansas, as a full season shrunk down to a three-hour Trey Lance Showcase.

“The NCAA needed leadership,” Carlton says. “There wasn’t anything but back-and-forth. They could have actually showed their worth instead of hiding behind the curtains. I have no idea why you’d let every conference make their own decision.”

His son came to despise the framework, this notion that his university had created one game simply so he could show off for scouts. That 26 of them showed up in early October, flying in as if flocking to Alabama-Clemson, representing two-thirds of the NFL, only bolstered the opposite sentiment. Same for the national broadcast on ESPN+.

It was the worst game of his college career, featuring his first (and, ultimately, only) interception. Even then, he ran for 143 yards, tallied four touchdowns and rallied the Bison for a fourth-quarter comeback, securing his undefeated career. As far as “bad” games go, this might have been the best in FCS history. But it also sent NFL scouts, these creatures of comparison, into a tizzy that only this particular ecosystem—quantifying a subjective process—could birth. Suddenly, Lance became inaccurate and susceptible to pressure, his success the product of inferior opposition. For some, one less-than-flawless game outweighs 16 near-flawless others. Others admit, anonymously of course, that they welcome the additional scrutiny, created by the oddest of circumstances, as it increases the chances that Lance, a player who promises to alter franchise fortunes, slips to their team.

The guesswork left out important factors. Like how three weeks before kickoff, his roommate tested positive for COVID-19, which meant 10 days of quarantine and missed practices. Lance also could have transferred to any number of major college programs and played a full season last fall. He never considered that option, out of loyalty. He called a meeting of the team’s leadership council, and they debated collective needs, like for the players who weren’t on full scholarship, who paid to play. Lance argued that one game would give them closure—and perhaps a chance to catch the eye of evaluators there to see the quarterback.

That Lance would then declare himself draft eligible and commence training seemed obvious. But the quarterback and his parents all say he wrestled with whether to come back far more than he let on. Carlton created another spreadsheet, naturally. Trey vacillated between options, changing his mind more than once. His coaches laid out an argument for why he should stay; they would support him regardless. Trey almost changed his mind again. “Playing two seasons in nine months, that’s going to take a toll on those players,” Angie says. “It just sped everything up. This never would’ve happened without COVID. Never.”

On the morning after the Central Arkansas win that, to the professional quibblers, felt more like a loss, Trey met his parents for breakfast. Angie struggled to hold back her emotions when he asked, “Am I doing the right thing?” He knew he was ready. So did she. But both were sad. College football had always been the dream, right up until Trey outgrew it.

On that same call in mid-March, Lance spins the pandemic as a positive. For a quarterback who obsesses about football, a restricted world gifted him more time to fixate, and fixation led to growth. The lost season, he posits, made him a better quarterback, not a worse one.

Lance flew to Atlanta soon after the non-showcase showcase and began his off-season of workouts with Avery, the private QB coach. Avery did not believe that Lance needed an extreme makeover; he already understood protections, drop backs and coverages that counterparts from spread systems often don’t learn in college.

Lance’s size-speed-ridiculous-arm-talent combo appeared tailored for traits desired in modern, mobile NFL quarterbacks—and Avery sought to make small refinements in throwing mechanics, footwork and motion efficiency. For instance, he helped Lance shorten his release while the duo trained six days each week for months, crisscrossing from Georgia to Florida to Fargo to Tennessee. Avery has come to believe Lance has the strongest arm of any quarterback he has trained, pros included. He also sees Lance as the “most natural” runner for a quarterback in this draft, prompting the Josh Allen comparisons. Like Allen, Lance combines a rare skill set with untapped potential; sometimes, Avery marveled at how Lance, in one day, could apply tweaks that took others weeks to master. He sees Lance less as a project and more as NFL-ready—“the most in his class”—right from the start.

As Audition 1 neared, Avery decided to tailor their script for teams in the quarterback market. He reached out to assistants he knew, brainstormed with NFL trainees for ideas, scoured tape of teams like the 49ers and Titans, and solicited suggestions from Lance, who conducted his own film study, just like at NDSU. Rather than only highlight Lance’s strengths, they added throws that would show how he fit into systems, building play-action into the early portion of the script and saving the jaw-dropping bombs for the end.

Avery came to like one play in particular: Y-Leak, a staple for Kyle Shanahan, Niners coach and owner of the third pick on Thursday. “I don’t think you’d see it in any other quarterback’s script,” Avery says. In the concept, two receivers split wide on one side of the field, then run crossing routes at varying depths. The QB fakes a handoff to the back and rolls while the tight end, originally aligned on the side of the formation opposite the receivers, feigns that he’s blocking. The tight end crosses the formation and “leaks” downfield, opposite the roll, into the space the receivers have vacated.

Lance completed 58 of the 66 throws—Y-Leak included—and Avery describes four incompletions as drops by unfamiliar receivers, since Lance’s regulars were unavailable due to NDSU’s spring season. Just as important: 30 teams sent representatives—and not just scouts, but head coaches and general managers. One GM in attendance says Lance struck him as dynamic. Another highlighted the quarterback’s significant improvement in footwork and motion efficiency.

Still, one day—even one very good day—would not put games back onto the 2020 schedule, and the polarizing nature of his predicament only drove Lance deeper. He disagreed with Avery’s recommendation that he should take the rest of March off. “We almost had to fight about that,” Lance says, laughing. “I feel guilty when I sit around.”

“Hopefully the scouts saw what they would be getting,” Hedberg mused, calling Lance “a guy that’s going to be the face of an NFL franchise.”

Lance called for the final time Thursday, shortly after his second pro day, which added another twist for NFL decision-makers. Wentz had told him to stay present, be himself. Allen had filmed a video message reminding Lance to ignore the vast array of predictions. This time, Lance added drift concepts emphasized by teams like the 49ers and Falcons. Again, he wowed, in front of another high-profile crowd of professional evaluators. This time, Shanahan attended, along with Niners GM John Lynch.

Afterward Lance’s mind drifted, to his home state where, 24 hours after that second pro day, Derek Chauvin would be convicted for the murder of George Floyd. In 2020 Lance joined in the fight against social injustice, marching in Fargo for Floyd or posting on Instagram in support of Breonna Taylor. Some of the reactions from his hometown were disappointing, but Lance cared more about his family’s mission statement, the one that hangs prominently in their dining room: We believe in making a difference in the world.

The draft remains an inexact science, fraught with bias, impacted by subjective factors. No quarterback taken in the first round between 2009 and ’16 still plays for the franchise that selected him. But Lance is an exacting person, only 20 but confident in his convictions. The scouts who fixate on 17 starts and the lost season are not lying, he says. He chose to consider the parts of conversations with them that felt more relevant, like what books he might listen to and what improvements he might make. He ignored the rest, same as he ignored the backlash he encountered for supporting the Black Lives Matter movement. “A glimmer of hope,” he calls the guilty verdict, noting that “there’s still a long way to go.”

On Thursday, Lance will wake up in Cleveland, and a life he couldn’t fathom just three years ago will become his new reality. He’ll host a dinner for family and friends the night before, seeking a “thin slice” of normalcy from the one group that won’t pass judgment. Then he’ll tug on a navy-blue suit and walk the red carpet, considering his future—team, platform, the impact he can make in the NFL and in the world.

That’s the thing about the most extraordinary prospect in the most peculiar draft in NFL history: He celebrates what separates him, from Marshall to Fargo, from Wing-T to FCS, from spreadsheets to activism and the near-flawless season to the one that disappeared. Lance isn’t bothered by how he arrived here, on the precipices of another spring day when everything will change again. In fact, he wants to be a face-of-the-franchise quarterback: uncommon in the NFL, too.

More SI Daily Covers:

• Alex Smith Healed Enough to Walk Away

• Trevor Lawrence Is Out to Prove Absolutely Nothing

• The Year of the Opt-Out Prospect